Exploration of the Moon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission to Jupiter

This book attempts to convey the creativity, Project A History of the Galileo Jupiter: To Mission The Galileo mission to Jupiter explored leadership, and vision that were necessary for the an exciting new frontier, had a major impact mission’s success. It is a book about dedicated people on planetary science, and provided invaluable and their scientific and engineering achievements. lessons for the design of spacecraft. This The Galileo mission faced many significant problems. mission amassed so many scientific firsts and Some of the most brilliant accomplishments and key discoveries that it can truly be called one of “work-arounds” of the Galileo staff occurred the most impressive feats of exploration of the precisely when these challenges arose. Throughout 20th century. In the words of John Casani, the the mission, engineers and scientists found ways to original project manager of the mission, “Galileo keep the spacecraft operational from a distance of was a way of demonstrating . just what U.S. nearly half a billion miles, enabling one of the most technology was capable of doing.” An engineer impressive voyages of scientific discovery. on the Galileo team expressed more personal * * * * * sentiments when she said, “I had never been a Michael Meltzer is an environmental part of something with such great scope . To scientist who has been writing about science know that the whole world was watching and and technology for nearly 30 years. His books hoping with us that this would work. We were and articles have investigated topics that include doing something for all mankind.” designing solar houses, preventing pollution in When Galileo lifted off from Kennedy electroplating shops, catching salmon with sonar and Space Center on 18 October 1989, it began an radar, and developing a sensor for examining Space interplanetary voyage that took it to Venus, to Michael Meltzer Michael Shuttle engines. -

Modeling and Adjustment of THEMIS IR Line Scanner Camera Image Measurements

Modeling and Adjustment of THEMIS IR Line Scanner Camera Image Measurements by Brent Archinal USGS Astrogeology Team 2255 N. Gemini Drive Flagstaff, AZ 86001 [email protected] As of 2004 December 9 Version 1.0 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. General 1.2. Conventions 2. Observations Equations and Their Partials 2.1. Line Scanner Camera Specific Modeling 2.2. Partials for New Parameters 2.2.1. Orientation Partials 2.2.2. Spatial Partials 2.2.3. Partials of the observations with respect to the parameters 2.2.4. Parameter Weighting 3. Adjustment Model 4. Implementation 4.1. Input/Output Changes 4.1.1. Image Measurements 4.1.2. SPICE Data 4.1.3. Program Control (Parameters) Information 4.2. Computational Changes 4.2.1. Generation of A priori Information 4.2.2. Partial derivatives 4.2.3. Solution Output 5. Testing and Near Term Work 6. Future Work Acknowledgements References Useful web sites Appendix I - Partial Transcription of Colvin (1992) Documentation Appendix II - HiRISE Sensor Model Information 1. Introduction 1.1 General The overall problem we’re solving is that we want to be able to set up the relationships between the coordinates of arbitrary physical points in space (e.g. ground points) and their coordinates on line scanner (or “pushbroom”) camera images. We then want to do a least squares solution in order to come up with consistent camera orientation and position information that represents these relationships accurately. For now, supported by funding from the NASA Critical Data Products initiative (for 2003 September to 2005 August), we will concentrate on handling the THEMIS IR camera system (Christensen et al., 2003). -

NASA's Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE)

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 13, EGU2011-5107-2, 2011 EGU General Assembly 2011 © Author(s) 2011 NASA’s Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE) Richard Elphic (1), Gregory Delory (1,2), Anthony Colaprete (1), Mihaly Horanyi (3), Paul Mahaffy (4), Butler Hine (1), Steven McClard (5), Joan Salute (6), Edwin Grayzeck (6), and Don Boroson (7) (1) NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA USA ([email protected]), (2) Space Sciences Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, CA USA, (3) Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO USA, (4) NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD USA, (5) LunarQuest Program Office, NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, AL USA, (6) Planetary Science Division, Science Mission Directorate, NASA, Washington, DC USA, (7) Lincoln Laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Lexington MA USA Nearly 40 years have passed since the last Apollo missions investigated the mysteries of the lunar atmosphere and the question of levitated lunar dust. The most important questions remain: what is the composition, structure and variability of the tenuous lunar exosphere? What are its origins, transport mechanisms, and loss processes? Is lofted lunar dust the cause of the horizon glow observed by the Surveyor missions and Apollo astronauts? How does such levitated dust arise and move, what is its density, and what is its ultimate fate? The US National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council decadal surveys and the recent “Scientific Context for Exploration of the Moon” (SCEM) reports have identified studies of the pristine state of the lunar atmosphere and dust environment as among the leading priorities for future lunar science missions. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

Optics, Basra, Cairo, Spectacles

International Journal of Optics and Applications 2014, 4(4): 110-113 DOI: 10.5923/j.optics.20140404.02 Alhazen, the Founder of Physiological Optics and Spectacles Nāsir pūyān (Nasser Pouyan) Tehran, 16616-18893, Iran Abstract Alhazen (c. 965 – c. 1039), Arabian mathematician and physicist with an unknown actual life who laid the foundation of physiological optics and came within an ace of discovery of the use of eyeglasses. He wrote extensively on algebra, geometry, and astronomy. Just the Beginnings of the 13th century, in Europe eyeglasses were used as an aid to vision, but Alhazen’s book “Kitab al – Manazir” (Book of Optics) included theories on refraction, reflection and the study of lenses and gave the first account of vision. It had great influence during the Middle Ages. In it, he explained that twilight was the result of the refraction of the sun’s rays in the earth’s atmosphere. The first Latin translation of Alhazen’s mathematical works was written in 1210 by a clergyman from Sussex, in England, Robert Grosseteste (1175 – 1253). His treatise on astrology was printed in Latin at Basle in 1572. Alhazen who was from Basra died in Cairo at the age of 73 (c. 1039). Keywords Optics, Basra, Cairo, Spectacles Ibn al-Haytham (c. 965 – c. 1038), known in the West who had pretended insane, once more was released from the Alhazen, and Avenna than1, who is considered as the father prison and received his belongings, and never applied for any of modern optics. He was from Basra [1] (in Iraq) and position. received his education in this city and Baghdad, but nothing is known about his actual life and teachers. -

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography on the Occasion of the 50Th Anniversary of Apollo 11 Moon Landing

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 moon landing Please note: A specific item in this catalogue may be sold or is on hold if the provided link to our online inventory (by clicking on the blue-highlighted author name) doesn't work! Milestones of Science Books phone +49 (0) 177 – 2 41 0006 www.milestone-books.de [email protected] Member of ILAB and VDA Catalogue 07-2019 Copyright © 2019 Milestones of Science Books. All rights reserved Page 2 of 71 Authors in Chronological Order Author Year No. Author Year No. BIRT, William 1869 7 SCHEINER, Christoph 1614 72 PROCTOR, Richard 1873 66 WILKINS, John 1640 87 NASMYTH, James 1874 58, 59, 60, 61 SCHYRLEUS DE RHEITA, Anton 1645 77 NEISON, Edmund 1876 62, 63 HEVELIUS, Johannes 1647 29 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm 1878 42, 43, 44 RICCIOLI, Giambattista 1651 67 SCHMIDT, Johann 1878 75 GALILEI, Galileo 1653 22 WEINEK, Ladislaus 1885 84 KIRCHER, Athanasius 1660 31 PRINZ, Wilhelm 1894 65 CHERUBIN D'ORLEANS, Capuchin 1671 8 ELGER, Thomas Gwyn 1895 15 EIMMART, Georg Christoph 1696 14 FAUTH, Philipp 1895 17 KEILL, John 1718 30 KRIEGER, Johann 1898 33 BIANCHINI, Francesco 1728 6 LOEWY, Maurice 1899 39, 40 DOPPELMAYR, Johann Gabriel 1730 11 FRANZ, Julius Heinrich 1901 21 MAUPERTUIS, Pierre Louis 1741 50 PICKERING, William 1904 64 WOLFF, Christian von 1747 88 FAUTH, Philipp 1907 18 CLAIRAUT, Alexis-Claude 1765 9 GOODACRE, Walter 1910 23 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1770 51 KRIEGER, Johann 1912 34 SAVOY, Gaspare 1770 71 LE MORVAN, Charles 1914 37 EULER, Leonhard 1772 16 WEGENER, Alfred 1921 83 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1775 52 GOODACRE, Walter 1931 24 SCHRÖTER, Johann Hieronymus 1791 76 FAUTH, Philipp 1932 19 GRUITHUISEN, Franz von Paula 1825 25 WILKINS, Hugh Percy 1937 86 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm Gotthelf 1824 41 USSR ACADEMY 1959 1 BEER, Wilhelm 1834 4 ARTHUR, David 1960 3 BEER, Wilhelm 1837 5 HACKMAN, Robert 1960 27 MÄDLER, Johann Heinrich 1837 49 KUIPER Gerard P. -

The Economic Impact of Physics Research in the UK: Satellite Navigation Case Study

The economic impact of physics research in the UK: Satellite Navigation Case Study A report for STFC November 2012 Contents Executive Summary................................................................................... 3 1 The science behind satellite navigation......................................... 4 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 1.2 The science................................................................................................ 4 1.3 STFC’s role in satellite navigation.............................................................. 6 1.4 Conclusions................................................................................................ 8 2 Economic impact of satellite navigation ........................................ 9 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Summary impact of GPS ........................................................................... 9 2.3 The need for Galileo................................................................................. 10 2.4 Definition of the satellite navigation industry............................................ 10 2.5 Methodological approach......................................................................... 11 2.6 Upstream direct impacts .......................................................................... 12 2.7 Downstream direct impacts..................................................................... -

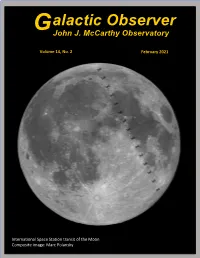

Alactic Observer

alactic Observer G John J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 14, No. 2 February 2021 International Space Station transit of the Moon Composite image: Marc Polansky February Astronomy Calendar and Space Exploration Almanac Bel'kovich (Long 90° E) Hercules (L) and Atlas (R) Posidonius Taurus-Littrow Six-Day-Old Moon mosaic Apollo 17 captured with an antique telescope built by John Benjamin Dancer. Dancer is credited with being the first to photograph the Moon in Tranquility Base England in February 1852 Apollo 11 Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites are visible in the images, as well as Mare Nectaris, one of the older impact basins on Mare Nectaris the Moon Altai Scarp Photos: Bill Cloutier 1 John J. McCarthy Observatory In This Issue Page Out the Window on Your Left ........................................................................3 Valentine Dome ..............................................................................................4 Rocket Trivia ..................................................................................................5 Mars Time (Landing of Perseverance) ...........................................................7 Destination: Jezero Crater ...............................................................................9 Revisiting an Exoplanet Discovery ...............................................................11 Moon Rock in the White House....................................................................13 Solar Beaming Project ..................................................................................14 -

Spacex CRS-4 National Aeronautics and Fourth Commercial Resupply Services Flight Space Administration

SpaceX CRS-4 National Aeronautics and Fourth Commercial Resupply Services Flight Space Administration to the International Space Station September 2014 OVERVIEW The Dragon spacecraft will be filled with more than 5,000 pounds of supplies and payloads, including critical materials to support 255 science and research investigations that will occur during Expeditions 41 and 42. Dragon will carry three powered cargo payloads in its pressurized section and two in its unpressurized trunk. Science payloads will enable model organism research using rodents, fruit flies and plants. A special science payload is the ISS-Rapid Scatterometer to monitor ocean surface wind speed and direction. Several new technology demonstrations aboard will enable bone density studies, test how a small satellite moves and positions itself in space using new thruster technology, and use the first 3-D printer in space for additive manufacturing. The mission also delivers IMAX cameras for filming during four increments and replacement batteries for the spacesuits. After four weeks at the space station, the spacecraft will return with about 3,800 pounds of cargo, including crew supplies, hardware and computer resources, science experiments, space station hardware, and four powered payloads. DRAGON CARGO LAUNCH ITEMS RETURN ITEMS TOTAL CARGO: 4885 lbs / 2216 kg 3276 lbs / 1486 kg · Crew Supplies 1380 lbs / 626 kg 132 lbs / 60 kg Crew care packages Crew provisions Food · Vehicle Hardware 403 lbs / 183 kg 937 lbs / 425 kg Crew Health Care System hardware Environment Control & Life Support equipment Electrical Power System hardware Extravehicular Robotics equipment Flight Crew Equipment Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency equipment · Science Investigations 1644 lbs / 746 kg 2075 lbs / 941 kg U.S. -

Sky and Telescope

SkyandTelescope.com The Lunar 100 By Charles A. Wood Just about every telescope user is familiar with French comet hunter Charles Messier's catalog of fuzzy objects. Messier's 18th-century listing of 109 galaxies, clusters, and nebulae contains some of the largest, brightest, and most visually interesting deep-sky treasures visible from the Northern Hemisphere. Little wonder that observing all the M objects is regarded as a virtual rite of passage for amateur astronomers. But the night sky offers an object that is larger, brighter, and more visually captivating than anything on Messier's list: the Moon. Yet many backyard astronomers never go beyond the astro-tourist stage to acquire the knowledge and understanding necessary to really appreciate what they're looking at, and how magnificent and amazing it truly is. Perhaps this is because after they identify a few of the Moon's most conspicuous features, many amateurs don't know where Many Lunar 100 selections are plainly visible in this image of the full Moon, while others require to look next. a more detailed view, different illumination, or favorable libration. North is up. S&T: Gary The Lunar 100 list is an attempt to provide Moon lovers with Seronik something akin to what deep-sky observers enjoy with the Messier catalog: a selection of telescopic sights to ignite interest and enhance understanding. Presented here is a selection of the Moon's 100 most interesting regions, craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and domes. I challenge observers to find and observe them all and, more important, to consider what each feature tells us about lunar and Earth history. -

NUCLEAR SAFETY LAUNCH APPROVAL: MULTI-MISSION LESSONS LEARNED Yale Chang the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory

ANS NETS 2018 – Nuclear and Emerging Technologies for Space Las Vegas, NV, February 26 – March 1, 2018, on CD-ROM, American Nuclear Society, LaGrange Park, IL (2018) NUCLEAR SAFETY LAUNCH APPROVAL: MULTI-MISSION LESSONS LEARNED Yale Chang The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, 11100 Johns Hopkins Rd, Laurel, MD 20723 240-228-5724; [email protected] Launching a NASA radioisotope power system (RPS) trajectory to Saturn used a Venus-Venus-Earth-Jupiter mission requires compliance with two Federal mandates: Gravity Assist (VVEJGA) maneuver, where the Earth the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) Gravity Assist (EGA) flyby was the primary nuclear safety and launch approval (LA), as directed by Presidential focus of NASA, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), the Directive/National Security Council Memorandum 25. Cassini Interagency Nuclear Safety Review Panel Nuclear safety launch approval lessons learned from (INSRP), and the public alike. A solid propellant fire test multiple NASA RPS missions, one Russian RPS mission, campaign addressed the MPF finding and led in part to two non-RPS launch accidents, and several solid the retrofit solid propellant breakup systems (BUSs) propellant fire test campaigns since 1996 are shown to designed and carried by MER-A and MER-B spacecraft have contributed to an ever-growing body of knowledge. and the deployment of plutonium detectors in the launch The launch accidents can be viewed as “unplanned area for PNH. The PNH mission decreased the calendar experiments” that provided real-world data. Lessons length of the NEPA/LA processes to less than 4 years by learned from the nuclear safety launch approval effort of incorporating lessons learned from previous missions and each mission or launch accident, and how they were tests in its spacecraft and mission designs and their applied to improve the NEPA/LA processes and nuclear NEPA/LA processes.