Life Streams: the Cuban and American Art of Alberto Rey Lynette M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ana Menéndez and Alberto Rey

College of the Holy Cross CrossWorks Spanish Department Faculty Scholarship Spanish Department 5-2009 The Memories of Others: Ana Menéndez and Alberto Rey Isabel Alvarez-Borland College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/span_fac_scholarship Part of the Modern Languages Commons, and the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Required Citation Alvarez-Borland, Isabel. "The Memories of Others: Ana Menéndez and Alberto Rey." Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas 42.1 (2009) : 11-20. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Spanish Department at CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish Department Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of CrossWorks. THE MEMORIES of OTHERS: ANA MENÉNDEZ AND ALBERTO REY Isabel Alvarez Borland “I live between two worlds, like a photograph that is always developing, never finishing, always in transition or perhaps translation, between past and present, English and Spanish, Cuba and the United States, the invisible and the visible, truths and lies.” María de los Angeles Lemus 1 How are the discourses of memory produced, conveyed, and negotiated within particular communities such as heritage Cuban American artists? A literature born of exile is a literature that by force relies on memory and imagination since the cultural reality that inspires it is no longer available to fuel the artists’ creativity. This is especially true of U.S. Cuban heritage writers who are twice -

The Complexities of Water Biological Regionalism: Bagmati River, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal

Kathmandu Valley, Nepal Valley, Kathmandu River, Biological Regionalism: Bagmati The Complexities of Water The Complexities of Water Biological Regionalism: Bagmati River, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal Alberto Rey Jason Dilworth The Complexities of Water Biological Regionalism: Bagmati River, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal Alberto Rey Jason Dilworth The Complexities of Water Biological Regionalism: Bagmati River, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal Alberto Rey Jason Dilworth This marigold chain was strung around a shrine between Pashupatinath and Guheswori Temples in Kathmandu. Marigolds symbolize trust in the Gods and their power to overcome obstacles and evils. The strong odor also keeps flies from the offerings. www.BagmatiRiverArtProject.com Dedicated to the Nepali People g]kfnL hgtfk|lt ;dlk{t Published by: Canadaway Press Fredonia, New York 14063 © 2016 Alberto Rey Charts and figures taken from the Bagmati River Expedition 2015. Nepal River Conservation Trust & Biosphere Association. Translation from English to Nepali by Prashant Das Project made possible with the support of the Kathmandu Contemporary Art Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal Text and Images unless otherwise noted: Alberto Rey Printed in China Onthemark LLC 75-5660 Kopiko St #C7 – 105 Kailua-Kona, HI 96740 ISBN: 978-0-9979644-0-0 Contents Project background Water, Water, Everywhere, 4 Nor Any Drop to Drink 114 Land of Contradictions Moving forward 18 129 Nepal and Kathmandu Valley Project Timeline 27 150 The Bagmati River in Kathmandu Valley Project Leaders 38 161 Bagmati River Expedition 2015 References 57 165 Detailed View of Four Sites from the Bagmati River Expedition 72 The Bagmati River Art Project could not have happened without the the Siddhartha Gallery in Kathmandu, Nepal. -

ECONOMÍA POLÍTICA ARGENTINA Cómo Revertir La Decadencia Argentina

SU PROHIBIDA REPRODUCCIÓN ECONOMÍA POLÍTICA ARGENTINA Cómo revertir la decadencia argentina SU PROHIBIDA REPRODUCCIÓN Conesa, Eduardo Economía Política Argentina / Eduardo Conesa; Luis Alberto Rey. - 1a ed. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: Prosa y Poesía Amerian Editores, 2020. 828 p.; 23 x 15 cm. ISBN 978-987-729-570-2 1. Economía Política Argentina. 2. Historia Económica Argentina. I. Rey, Luis Alberto. II. Título. CDD 338.982 SU PROHIBIDA www.eduardoconesa.com.ar www.diputadoconesa.com Twitter: edconesa Facebook: eduardo.conesa.144 REPRODUCCIÓN PROSA Editores, 2020 Uruguay 1371 - C.A.Bs.As. Tel: 4815-6031 / 0448 [email protected] www.prosaeditores.com.ar ISBN Nro: 978-987-729-570-2 Hecho el depósito que marca la ley 11.723 Reservados todos los derechos. Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial por cualquier medio o procedimiento sin permiso escrito del autor. ECONOMÍA POLÍTICA ARGENTINA Cómo revertir la decadencia argentina POR EDUARDO R. CONESA Y LUIS A. REY Con la colaboración SUde Gustavo Zunino PROHIBIDA REPRODUCCIÓN SU PROHIBIDA REPRODUCCIÓN ÍNDICE PRÓLOGO 11 INTRODUCCIÓN 19 La Economía Política de la Revolución de Mayo CAPÍTULO I 47 El modelo clásico de la Economía Política CAPÍTULO II 77 La falencia de la Economía Política clásica ante los tipos de cambio fijos con patrón oro entre 1923 y 1944 CAPÍTULO III 93 El tipo de cambio real como variable político-estratégica crucial para el desarrollo económico CAPÍTULO IV SU 109 La Argentina liberalPROHIBIDA desarrollista de 1860-1943: tipo de cambio competitivo, educación, exportación y creci- miento económico CAPÍTULO V 141 El amiguismo de los nombramientosREPRODUCCIÓN en el Estado y la decadencia argentina CAPÍTULO VI 161 La revolución keynesiana, la función del consumo y sus cuatro multiplicadores de la actividad económica. -

Alberto Rey's Balsa Series in the Cuban American Imagination

College of the Holy Cross CrossWorks Spanish Department Faculty Scholarship Spanish Department 2014 Alberto Rey’s Balsa Series in the Cuban American Imagination Isabel Alvarez-Borland College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/span_fac_scholarship Part of the Modern Languages Commons, Painting Commons, and the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Required Citation Alvarez-Borland, Isabel. "Alberto Rey’s Balsa Series in the Cuban American Imagination." Life Streams: Alberto Rey’s Cuban and American Art, edited by Lynette M.F. Bosch and Mark Denaci, SUNY Press, 2014, pp. 67-83. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Spanish Department at CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish Department Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of CrossWorks. Alberto Rey’s Balsa Series in the Cuban American Imagination Isabel Alvarez Borland Then I saw that the days and the nights were passing and I was still alive, drinking sea water and putting my head in the water, as long as I could, to refresh my burning face….When the raft came apart each one grabbed a tire or one of the planks. Whatever we could. We had to cling to something to survive. .But I was sure I wasn’t going to perish….It was like the end of a novel, horrible. Someone had to remain to tell the story. Guillermo Cabrera Infante In one of the final vignettes of Cabrera Infante’s View of Dawn in the Tropics (1974), history becomes dramatized in a first-person narrative as life is pitted against death.1 For Cabrera Infante (1929-2005), the use of a balsero perspective creates a new empathy in the reader, who is immediately drawn to the lives of those who speak and to their suffering. -

Curriculum Vitae

1 LYNETTE M.F. BOSCH Curriculum Vitae Contact: State University of New York, Geneseo Department of Art History- Brodie Hall Geneseo, New York 14454 Telephone: 585-260-1888 [email protected] EDUCATION 1985 - Ph.D. Princeton University, Department of Art & Archaeology Areas of Focus: Renaissance/Baroque (Spain, Italy, Netherlands) 1981 - M.A. Princeton University, Department of Art & Archaeology 1978 - M.A. Hunter College, City University of New York Areas of Focus: Renaissance (Italian & Northern) 1974 - B.A. Queens College, City University of New York Dean’s List Major: Art History Minor: Classics EMPLOYMENT 2016 – SUNY Distinguished Professor and Chair, Department of Art History, SUNY Geneseo 2015 - Continuing – Chair, Department of Art History, SUNY, Geneseo 2014 – Coordinator Museum Studies Minor, SUNY, Geneseo 2005 – Professor of Art History, SUNY, Geneseo 2000 – Associate Professor of Art History, SUNY, Geneseo 1999 – Assistant Professor of Art History, SUNY, Geneseo 1992-98 - Assistant Professor of Art History, Brandeis University 2 1990-92 - Assistant Professor in Art History, SUNY, Cortland 1983-94 - Visiting Assistant Professor in Art History: School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (1994) Cornell University (Spring 1992) Seton Hall University (1988-1990) Tufts University (1986-1988) Hunter College, CUNY (1983-1986) Lafayette College (1984-1986) Trenton State College (1983-1984) FELLOWSHIPS, HONORS AND AWARDS 2017 – SUNY, Geneseo, Geneseo Foundation Research Award 2014 – Rothkopf Scholar Award, Lafayette College, Regional recognition -

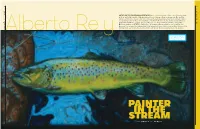

Painter in the Stream by Nancy J

72 73 AUGUST AUGUST BUFFALOSPREE ARTIST AND FLY FISHERMAN ALBERTO REY was born in Agramonte, Cuba, a small farming town 2019 an hour and a half outside of Havana named for revolutionary Ignacio Agramonte. Rey and his family later moved to Mexico City (where they were granted political asylum), then Miami, then to a coal mining town in Western Pennsylvania. Eventually, Rey’s academic studies found him in the .COM FLY FISHING FLY University at Buffalo’s graduate program, where he received an MFA in painting and drawing. He began teaching at SUNY Fredonia, where he became a distinguished professor, and lived in Dunkirk. This is where his introduction to fly fishing took place. Rey became an Orvis Endorsed Fly Alberto Re y Fishing Guide and now helps others learn the artist’s favorite sport and method of meditation. Rey’s painting Brown Trout, Willowemoc River, Catskills, New York PAINTER IN THE STREAM BY NANCY J. PARISI 74 75 In 1998, Rey co-founded what is now called Children of the Stream, an AUGUST AUGUST interdisciplinary nonprofit teaching kids fly fishing and conservation. The group BUFFALOSPREE meets weekly and is open to kids and adults in his community; Rey provides all the necessary gear. “I found out that there were salmon running up the Canadaway 2019 stream from Lake Erie,” Rey recalls. “I was getting ready for tenure, so I put fishing on the back burner. But, once I got tenure, I started researching fly fishing, reading everything that I could get my hands on, and talking to other fishermen at the .COM FLY FISHING FLY college. -

Lewthwaite, Stephanie (2017) “Seeing in the Dark”: the Aesthetics of Disappearance and Remembrance in the Work of Alberto Rey

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Nottingham ePrints Lewthwaite, Stephanie (2017) “Seeing in the dark”: the aesthetics of disappearance and remembrance in the work of Alberto Rey. Journal of American Studies, 51 (2). pp. 591-621. ISSN 0021-8758 Access from the University of Nottingham repository: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/45279/5/JAS%20Lewthwaite%20Rey%20article.pdf Copyright and reuse: The Nottingham ePrints service makes this work by researchers of the University of Nottingham available open access under the following conditions. This article is made available under the University of Nottingham End User licence and may be reused according to the conditions of the licence. For more details see: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/end_user_agreement.pdf A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the repository url above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information, please contact [email protected] “Seeing in the Dark” The Aesthetics of Disappearance and Remembrance in the Work of Alberto Rey ABSTRACT This article examines how contemporary Cuban American artists have experimented with visual languages of trauma to construct an intergenerational memory about the losses of exile and migration. It considers the work of artist Alberto Rey, and his layering of individual loss onto other, traumatic episodes in the history of the Cuban diaspora. -

Download a Searchable PDF of This Publication

<H.<itI~&tt9 dO#lt@W8f30t~%~-/kit9 d@ftt@t Buffalo, New Yoik Big Orbit Gallery and Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center are a telescope, Rey's perspective on his past is lucid, showing pleased to host the dual-site exhibition My Private Addiction to clear evidence of the Cuban condition, but is vignetted by the Lies by Cuban-born, Western New York artist Alberto Rey. This effects of distance and time. While highly charged with showing comprises a dynamic survey of the artist's most recent personal invocations of Cuban identity, his vision has been work and is accompanied by a comprehensive essay entitled moderated by the missing context provided by direct experi- 'Reappropriating Paradise" by Dr. Johanna Drucker. The ence. curators and artist would like to extend their personal grati- tude to Johanna for her insightful comments and contribution In 1998, thirty-six years after leaving as a child, Alberto Rey to this exhibition and catalogue. returned to Cuba for the first time. During his visit Rey ab- sorbed a flood of direct experience which forced him to con- For the last twelve years the work of Alberto Rey has at- template the depictions of "reality" and "nostalgia" expressed tempted to reconcile the disparate pieces of his Cuban- in his work. The new perspective achieved as a result of his American identity through an uneasy fusion. Born to Cuban trip compelled Rey to see himself and his work in a different exiles who received political asylum through Mexico and moved light. Rey now states that his artistic practice results in the to America when he was a child, Rey has been limited to a ''creation of lies" - born out of a need to embrace a reality remote sensing of Cuban culture, its history and private which is not necessarily the truth. -

“Seeing in the Dark” the Aesthetics of Disappearance and Remembrance

“Seeing in the Dark” The Aesthetics of Disappearance and Remembrance in the Work of Alberto Rey ABSTRACT This article examines how contemporary Cuban American artists have experimented with visual languages of trauma to construct an intergenerational memory about the losses of exile and migration. It considers the work of artist Alberto Rey, and his layering of individual loss onto other, traumatic episodes in the history of the Cuban diaspora. In the series Las Balsas (The Rafts, 1995-99), Rey explores the impact of the balsero (rafter) crisis of 1994 by transforming objects left behind by Cuban rafters on their sometimes ill-fated journeys to the United States into commemorative relics. By playing on a memory of absence and the misplacement of objects found along the migration route of the Florida Straits, Rey’s visual language transmits the memory of grief across time, space and generational divides. Rey’s visual strategies are part of an “extended memory” tied to the aesthetics of disappearance and remembrance in contemporary Cuban American art. His use of objects as powerful memory texts that serve to bring fragmented autobiographical, family, and intergenerational testimonies of loss together, suggests how visual artists can provide us with more collective, participatory and redemptive models of memory work. 1 Trauma, and the traumatic experiences that generate trauma, often defy representation. Literary scholar Cathy Caruth argues that “the most direct seeing of a violent event may occur as an absolute inability to know it.”1 Traumatic -

Enrique Martínez Celaya Biography — Born 1964, Havana, Cuba Lives

Enrique Martínez Celaya Biography — Born 1964, Havana, Cuba Lives and works in Los Angeles Education and Professorships — 2014 Montgomery Fellow, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire 2007-10 Visiting Presidential Professor, University of Nebraska 1994-2003 Associate Professor, Pomona College and Claremont Graduate University 1994 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine 1994 MFA, Painting, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 1988 MS, Quantum Electronics, University of California, Berkeley, California 1986 BS, Applied & Engineering Physics, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York Selected Solo Exhibitions — 2017 Galerie Judin, Berlin, Germany Jack Shainman Gallery, New York 2016 Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Parafin, London, United Kingdom 2015 Jack Shainman Gallery, New York LA Louver, Venice, California 2014 Parafin, London, United Kingdom Galleri Andersson/Sandström, Umeå, Sweden 2013 Strandverket Konsthall, Marstrand, Sweden SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe, New Mexico Fredric Snitze Gallery, Miami, Florida James Kelly Contemporary, Santa Fe, New Mexico 2012 The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia LA Louver, Venice, California Galleri Andersson/Sandström, Stockholm, Sweden Galeria Joan Prats, Barcelona, Spain 2011 Miami Art Museum, Miami, Florida LA Louver Gallery, Venice, California Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney, Australia 2010 Simon Lee Gallery, London, United Kingdom Cathedral of Saint John the Divine, New York, New York Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, Colorado 2009 Akira Ikeda Gallery, -

Exhibition History Alberto Rey

Exhibition History Alberto Rey Solo Exhibitions 2010 Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History, Jamestown, NY Lightwell Gallery, University of Buffalo Art Gallery, Center for the Arts, Buffalo, NY 2009 Chace-Randall Gallery, Andes, NY 2008 Washington and Lee University, Lexington, VA 2007 Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 2005 El Museo Francisco Oller y Diego Rivera, Buffalo, NY Erie Art Museum, Erie, PA Abud Foundation for the Arts, Lawrenceville, NJ 2004 I.G.F.A. Museum, Fort Lauderdale, Fl 2002 Erpf Gallery of the Catskill Center, Arkville, NY Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History – Jamestown, NY Buffalo Arts Studio – Buffalo, NY 2001 Adams Art Gallery – Dunkirk, NY 1999-00 Bertha V. B. Lederer Gallery – State University of New York at Geneseo, NY Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center – Buffalo, NY Big Orbit Gallery – Buffalo, NY Weeks Gallery – Jamestown Community College, Jamestown, NY 1997 Sharidan Art Gallery – Kutztown University, Kutztown ,PA Richard Brush Art Gallery – St. Lawrence University, Canton NY Miramar Gallery – Sarasota, FL 1996 Galeria Nina Menocal – Mexico City, Mexico Meridian Gallery – San Francisco, CA 1995 Schneider Museum of Art – Southern Oregon State College – Ashland, OR Wayne County Council for the Arts – Lyons, NY Castellani Museum – Niagara University, NY Howard Yezerski Gallery – Boston, MA 1993 Mercer Gallery – Monroe Community College, Rochester, NY INTAR Gallery – New York City, NY 1992 Olean Public Library – Olean, NY Nina Freudenheim Gallery -

4Th Rochester Biennial Celebrates Regional Art Exhibition Opens July 25 at Rochester’S Memorial Art Gallery

Public Relations Office · 500 University Avenue · Rochester, NY 14607-1484 585.276.8900 · 585.473.6266 fax · mag.rochester.edu NEWS July 22, 2010 EXHIBITION FACT SHEET Title: 4TH ROCHESTE R BIENNIAL When: July 25–September 26, 2010 Description: Each summer, MAG presents a showcases of regional art—in alternate years, the juried Rochester-Finger Lakes Exhibition or the invitational Rochester Biennial. For this year’s Biennial, the Gallery’s director and curators have selected A. E. Ted Aub of Geneva (sculpture), Anne Havens of Rochester (multiple media), Rick Hock of Rochester (digital imag- ing), Alberto Rey of Fredonia (painting and video), Julianna Furlong Williams of Spencerport (painting), and Lawrence M. “Judd” Williams of Spencerport (sculpture). As in previous years, one artist (Havens) was selected on the strength of her work in last year’s Rochester-Finger Lakes Exhibition. Credits: This exhibition is sponsored by the Elaine P. and Richard U. Wilson Foundation, with additional support from ESL Federal Credit Union, Edward and Marilynn McDonald, and the Rubens Family Foundation. Special events: These include an Exhibition Party (July 24) and lectures by five of the artists (July 29, August 19, and September 9, 16 & 23). For details, see attached release. “Meet the Artist” Use your cell phone to hear all six artists talk about their work. The tour is free but cell phone tours: regular cell phone charges apply. Hours: Wednesday–Sunday 11 am–5 pm and Thursday until 9 pm. Closed Mondays and Tuesdays. Admission: $10; senior citizens, $6; college students with ID and children 6–18, $5. Always free to members, UR students, and children 5 and under.