A Conversation with Rudolf Jaenisch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Therapeutic Cloning Gives Silenced Genes a Second Voice

NEWS p1007 Tricky Fix: p1009 Bohemian p1010 Better than A vaccine for cocaine brain: Neuroscientist Prozac: What’s next in addiction poses John Hardy bucks antidepressant drug ethical dilemmas. the trends. development? Therapeutic cloning gives silenced genes a second voice As controversy continues on therapeutic experiments in Xenopus embryos, is the removal silencing may not be permanent.” cloning to create human embryos, applying the of methyl groups from specific regions of DNA. Jaenisch and his colleagues have also shown technique—also known as somatic cell nuclear This may be a necessary step in the epigenetic that nuclei from a skin cancer cell can be repro- transfer—in animals is generating important reprogramming of the nucleus, the researchers grammed to direct normal development of a insights into disease development. suggest in the October Nature Cell Biology. mouse embryo—meaning that removal of the Some scientists are using the approach to As cells differentiate, they accrue many epigenetic alterations is enough to restore cells study epigenetic alterations—chromosomal other types of epigenetic alterations, such as to normal (Genes Dev.18,1875–1885; 2004).An modifications that do not alter the DNA the addition of phosphates or removal of earlier study reported similar results with brain sequence—which can cause cancer. “A acetyl groups from histones, or chromosomal tumor cells (Cancer Res. 63, 2733–2736; 2003). principal question in cancer research is what proteins, and trigger changes in chromatin Based on such findings, pharmaceutical part of the cancer cell phenotype comes from structure. Defects in these processes have been companies are racing to develop and test ‘epige- genetic defects and what part is epigenetic,”says linked to cancer and other diseases. -

Liberal Arts Science $600 Million in Support of Undergraduate Science Education

Janelia Update |||| Roger Tsien |||| Ask a Scientist SUMMER 2004 www.hhmi.org/bulletin LIBERAL ARTS SCIENCE In science and teaching— and preparing future investigators—liberal arts colleges earn an A+. C O N T E N T S Summer 2004 || Volume 17 Number 2 FEATURES 22 10 10 A Wellspring of Scientists [COVER STORY] When it comes to producing science Ph.D.s, liberal arts colleges are at the head of the class. By Christopher Connell 22 Cells Aglow Combining aesthetics with shrewd science, Roger Tsien found a bet- ter way to look at cells—and helped to revolutionize several scientif-ic disciplines. By Diana Steele 28 Night Science Like to take risks and tackle intractable problems? As construction motors on at Janelia Farm, the call is out for venturesome scientists with big research ideas. By Mary Beth Gardiner DEPARTMENTS 02 I N S T I T U T E N E W S HHMI Announces New 34 Investigator Competition | Undergraduate Science: $50 Million in New Grants 03 PRESIDENT’S LETTER The Scientific Apprenticeship U P F R O N T 04 New Discoveries Propel Stem Cell Research 06 Sleeper’s Hold on Science 08 Ask a Scientist 27 I N T E R V I E W Toward Détente on Stem Cell Research 33 G R A N T S Extending hhmi’s Global Outreach | Institute Awards Two Grants for Science Education Programs 34 INSTITUTE NEWS Bye-Bye Bio 101 NEWS & NOTES 36 Saving the Children 37 Six Antigens at a Time 38 The Emergence of Resistance 40 39 Hidden Potential 39 Remembering Santiago 40 Models and Mentors 41 Tracking the Transgenic Fly 42 Conduct Beyond Reproach 43 The 1918 Flu: Case Solved 44 HHMI LAB BOOK 46 N O T A B E N E 49 INSIDE HHMI Dollars and Sense ON THE COVER: Nancy H. -

About Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research Selected

About Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research Selected Achievements in FOUNDING VISION Biomedical Science Whitehead Institute is a nonprofit, independent biomedical research institute with pioneering programs in cancer research, developmental biology, genetics, and Isolated the first tumor suppressor genomics. It was founded in 1982 through the generosity of Edwin C. "Jack" Whitehead, gene, the retinoblastoma gene, and a businessman and philanthropist who sought to create a new type of research created the first genetically defined institution, one that would exist outside the boundaries of a traditional academic human cancer cells. (Weinberg) institution, and yet, through a teaching affiliation with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), offer all the intellectual, collegial, and scientific benefits of a leading Isolated key genes involved in diabetes, research university. hypertension, leukemia, and obesity. (Lodish) WHITEHEAD INSTITUTE TODAY True to its founding vision, the Institute gives outstanding investigators broad freedom Mapped and cloned the male- to pursue new ideas, encourages novel collaborations among investigators, and determining Y chromosome, revealing a accelerates the path of scientific discovery. Research at Whitehead Institute is unique self-repair mechanism. (Page) conducted by 22 principal investigators (Members and Fellows) and approximately 300 visiting scientists, postdoctoral fellows, graduate students, and undergraduate Developed a method for genetically students from around the world. Whitehead Institute is affiliated with MIT in its engineering salt- and drought-tolerant teaching activities but wholly responsible for its own research programs, governance, plants. (Fink) and finance. Developed the first comprehensive cellular LEADERSHIP network describing how the yeast Whitehead Institute is guided by a distinguished Board of Directors, chaired by Sarah genome produces life. -

Rudolf Jaenisch

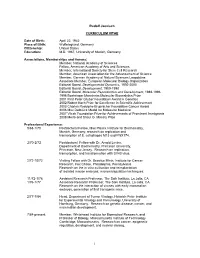

Rudolf Jaenisch CURRICULUM VITAE Date of Birth: April 22, 1942 Place of Birth: Wolfelsgrund, Germany Citizenship: United States Education: M.D. 1967, University of Munich, Germany Associations, Memberships and Honors: Member, National Academy of Sciences Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences Member, International Society for Stem Cell Research Member, American Association for the Advancement of Science Member, German Academy of Natural Sciences Leopoldina Associate Member, European Molecular Biology Organization Editorial Board, Developmental Dynamics, 1992-2000 Editorial Board, Development, 1989-1998 Editorial Board, Molecular Reproduction and Development, 1988-1996 1996 Boehringer Mannheim Molecular Bioanalytics Prize 2001 First Peter Gruber Foundation Award in Genetics 2002 Robert Koch Prize for Excellence in Scientific Achievement 2003 Charles Rodolphe Brupracher Foundation Cancer Award 2006 Max Delbrück Medal for Molecular Medicine 2007 Vilcek Foundation Prize for Achievements of Prominent Immigrants 2008 Meira and Shaul G. Massry Prize Professional Experience: 9/68-1/70 Postdoctoral Fellow, Max Planck Institute for Biochemistry, Munich, Germany; research on replication and transcription of E. coli phages M13 and PhiX174. 2/70-2/72 Postdoctoral Fellow with Dr. Arnold Levine, Department of Biochemistry, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey. Research on replication, transcription, and transformation with SV40 virus. 2/72-10/72 Visiting Fellow with Dr. Beatrice Mintz, Institute for Cancer Research, Fox Chase, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Research on the in vitro cultivation and reimplantation of isolated mouse embryos; micromanipulation techniques. 11/72-1/76 Assistant Research Professor, The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA 1/76-1/77 Associate Research Professor, The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA Research on the interaction of viruses with early mammalian embryos, generation of first transgenic mice. -

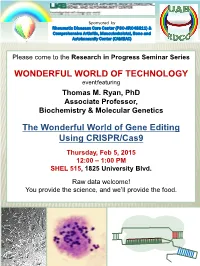

The Wonderful World of Gene Editing Using CRISPR/Cas9

Sponsored by Rheumatic Diseases Core Center (P30-AR048311) & Comprehensive Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, Bone and Autoimmunity Center (CAMBAC) Please come to the Research in Progress Seminar Series WONDERFUL WORLD OF TECHNOLOGY event featuring Thomas M. Ryan, PhD Associate Professor, Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics The Wonderful World of Gene Editing Using CRISPR/Cas9 Thursday, Feb 5, 2015 12:00 – 1:00 PM SHEL 515, 1825 University Blvd. Raw data welcome! You provide the science, and we’ll provide the food. The Wonderful World of Gene Editing Using CRISPR/Cas9 2/5/2015 Thomas M. Ryan, PhD Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics Regenerative Medicine Patient Transplant back Somatic Cell into patient Biopsy Derive Isogenic In vitro Pluripotent differentiation Stem Cells Corrected Repair DNA Stem Cells lesion Gene Correction by Homologous Recombination in Pluripotent Stem Cells Mouse: Homologous recombination (HR) methodology in murine ES cells is relatively straight forward. Gene targeting (knockouts, knockins, etc.) using targeting constructs with 5’ and 3’ homology regions flanking a selectable marker have been used to modify the mouse genome for over 25 years. Human: Gene correction by HR has proven much more difficult in human ES/iPS cells. Their slower growth and lower plating efficiencies have resulted in only a handful of genes to be targeted by standard techniques. Newer gene correction methods with higher efficiencies are needed. Humanized Hb Mouse Model: Human gA Globin Knock-In LCR ey h0 h1h2 maj min g A hyg CRE ey h0 h1 h2 g A LCR gAKI Mario Capecchi, Martin Evans, and Oliver Smithies were awarded the Noble Prize for Physiology and Medicine in 2007 for this “Gene Targeting” technique. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2011 Remarks on Presenting The

Administration of Barack Obama, 2011 Remarks on Presenting the National Medal of Science and the National Medal of Technology and Innovation October 21, 2011 Welcome, everybody. Please have a seat. It is a great pleasure to be with so many outstanding innovators and inventors. And I'm glad we could convince them all to take a day off—[laughter]—to accept our Nation's highest honor when it comes to inventions and innovation, and that is the National Medals of Science and the National Medals of Technology and Innovation. It's safe to say that this is a group that makes all of us really embarrassed about our old science projects. [Laughter] You know, the volcano with the stuff coming out—[laughter]— with the baking soda inside. Apparently, that was not a cutting-edge achievement— [laughter]—even though our parents told us it was really terrific. But thanks to the men and women on the stage, we are one step closer to curing diseases like cancer and Parkinson's. Because of their work, soldiers can see the enemy at night and grandparents can see the pictures of their grandchildren instantly and constantly. Planes are safer, satellites are cheaper, and our energy grid is more efficient, thanks to the breakthroughs that they have made. And even though these folks have not sought out the kind of celebrity that lands you on the cover of People magazine, the truth is that today's honorees have made a bigger difference in our lives than most of us will ever realize. When we fill up our cars, talk on our cell phones, or take a lifesaving drug, we don't always think about the ideas and the effort that made it all possible. -

Rudolf Jaenisch

RUDOLF JAENISCH Date of Birth: April 22, 1942 Place of Birth: Wolfelsgrund, Germany Citizenship: United States Education: M.D. 1967, University of Munich, Germany Associations, Memberships and Honors: Member, National Academy of Sciences Member, National Institute of Medicine Member, International Society for Stem Cell Research Member, American Association for the Advancement of Science Member, German Academy of Natural Sciences Leopoldina Associate Member, European Molecular Biology Organization Editorial Board, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2004- Editorial Board, Developmental Dynamics, 1992-2000 1996 Boehringer Mannheim Molecular Bioanalytics Prize 2001 First Peter Gruber Foundation Award in Genetics 2002 Robert Koch Prize for Excellence in Scientific Achievement 2003 Charles Rodolphe Brupracher Foundation Cancer Award 2006 Max Delbrück Medal for Molecular Medicine 2007 Vilcek Foundation Prize for Achievements of Prominent Immigrants 2008 Meira and Shaul G. Massry Prize 2009 James R. Killian Jr. Faculty Achievement Award 2009 Ernst Schering Prize 2010 Orden Pour le Mérite 2010 Kazemi Prize of the Royan Institute 2010 Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany 2011 MGH Warren Triennial Prize 2011 Wolf Prize for Medicine 2011 United States National Medal of Science 2011 J. Allyn Taylor International Prize in Medicine 2012 ISSCR McEwen Award for Innovation 2012-Vice President, International Society for Stem Cell Research 2013 Franklin Institute Laureate Professional Experience: 9/68-1/70 Postdoctoral Fellow, Max Planck Institute for Biochemistry, Munich; replication and transcription of E. coli phages M13 and PhiX174. 2/70-2/72 Postdoctoral Fellow with Dr. Arnold Levine, Department of Biochemistry, Princeton University; Replication, transcription, and transformation with SV40 virus. 2/72-10/72 Visiting Fellow with Dr. -

April 8-11, 2019 the 2019 Franklin Institute Laureates the 2019 Franklin Institute AWARDS CONVOCATION APRIL 8–11, 2019

april 8-11, 2019 The 2019 Franklin Institute Laureates The 2019 Franklin Institute AWARDS CONVOCATION APRIL 8–11, 2019 Welcome to The Franklin Institute Awards, the range of disciplines. The week culminates in a grand oldest comprehensive science and technology medaling ceremony, befitting the distinction of this awards program in the United States. Each year, the historic awards program. Institute recognizes extraordinary individuals who In this convocation book, you will find a schedule of are shaping our world through their groundbreaking these events and biographies of our 2019 laureates. achievements in science, engineering, and business. We invite you to read about each one and to attend We celebrate them as modern day exemplars of our the events to learn even more. Unless noted otherwise, namesake, Benjamin Franklin, whose impact as a all events are free and open to the public and located scientist, inventor, and statesman remains unmatched in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. in American history. Along with our laureates, we honor Franklin’s legacy, which has inspired the We hope this year’s remarkable class of laureates Institute’s mission since its inception in 1824. sparks your curiosity as much as they have ours. We look forward to seeing you during The Franklin From shedding light on the mechanisms of human Institute Awards Week. memory to sparking a revolution in machine learning, from sounding the alarm about an environmental crisis to making manufacturing greener, from unlocking the mysteries of cancer to developing revolutionary medical technologies, and from making the world III better connected to steering an industry giant with purpose, this year’s Franklin Institute laureates each reflect Ben Franklin’s trailblazing spirit. -

2007 Annual Report

At the 25th anniversary kickoff event, Founding Member Robert Weinberg debuts a time capsule that will store Whitehead artifacts. 2007 Annual Report Non-Profit Org. US Postage Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research PAID Nine Cambridge Center Cambridge, MA Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142-1479 Permit No. 56998 Below: Taken by a deep-ultraviolet microscope, this image shows how the mass of nucleic acids is Whitehead Institute distributed in a mouse macrophage (a kind of immune cell). Image by 2007 Annual Report Benjamin Zeskind, Paul Matsudaira’s laboratory. 1 Director’s letter 3 Scientific highlights 6 Research stories 12 Principal investigators 33 25th anniversary 34 Whitehead news Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research 36 Public outreach is a nonprofit research and educational institution. Wholly independent in its 38 Financial summary governance, finances and research programs, Whitehead shares a teaching affiliation 40 Leadership with Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Whitehead brings together a small group of world-class biomedical researchers in a highly collaborative and supportive environment and empowers them to pursue the questions that engage them most. Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research 9 Cambridge Center on the cover: Studying how cells regulate Cambridge, MA 02142 their growth, David Sabatini’s laboratory 617.258.5000 has shown that Rag family proteins www.whitehead.mit.edu regulate the location of a key protein complex called mTORC1 in the presence of nutrients. Here, mTOR is marked in green, DNA in blue and the Rab7 protein in red. From top to bottom in the sequence here, as the cell is stimulated with amino acids, mTOR moves to be localized in a compartment near the nucleus. -

March of Dimes Prize in Developmental Biology Recipient List

MARCH OF DIMES PRIZE IN DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY RECIPIENT LIST 2015 Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute Rudolf Jaenisch, MD Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, For pioneering work in human cytogenetics and the normal and and Professor of Biology abnormal function and behavior of the X and Y chromosomes. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 2010 For devising innovative technologies that elucidated long-standing Shinya Yamanaka, MD, PhD * dilemmas in developmental biology, for recognizing the L.K. Whittier Foundation Investigator in Stem Cell Biology transformative significance on cellular function of epigenetic Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease programming, and for applying the power of induced pluripotent Professor, University of California, San Francisco stem cells to novel discoveries. Director, Center for iPS Cell Research and Application 2014 For research on how certain master genes and protein signals regulate Huda Y. Zoghbi, MD formation and growth of organs such as the brain and limbs during Professor, Departments of Pediatrics; Molecular and Human Genetics; embryonic and fetal development. Neurology; Neuroscience; Programs in Cell and Molecular Biology and Developmental Biology 2009 Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX Kevin P. Campbell, PhD Carver Chair, Department of Molecular Physiology & Biophysics For pioneering work evolving from discovery that mutations in the X- Director of the Wellstone Muscular Dystrophy Cooperative Research linked MECP2 cause Rett syndrome and for studies elucidating the Center maintenance role of this epigenetic regulator in different neurons. Professor of Neurology and Internal Medicine 2013 University of Iowa, Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine, Eric Olson, PhD Iowa City, Iowa Annie and Willie Nelson Professorship in Stem Cell Research & Louis M. -

Genome Editing in Neurosciences Edition Du Génome Et Neurosciences

Genome editing in neurosciences Edition du génome et neurosciences Paris - April 22, 2016 Genome editing in neurosciences Paris - April 22, 2016 Innovations in molecular biology are allowing neuroscientists to study the brain with unprecedented resolution, from the level of single molecules to integrated gene circuits. Chief among these innovations is the CRISPR-Cas genome editing technology, which has the precision and scalability to tackle the complexity of the brain. This Colloque Médecine et Recherche brings together experts from around the world that are applying genome editing to address important challenges in neuroscience, including basic biology in model organisms that has the power to reveal systems-level insight into how the nervous system develops and functions as well as research focused on understanding and treating human neurological disorders. We hope that you will join us in Paris for this exciting day to explore how genome editing is advancing neuroscience research and meet some of the leading researchers in this field. Les innovations en biologie moléculaire permettent d’étudier le cerveau avec une résolution inégalée, depuis les molécules jusqu’aux circuits géniques intégrés. La principale innovation concerne une technologie de modification du génome, CRISPR-Cas, qui offre précision et flexibilité afin d’aborder l’étude de la complexité du cerveau. Ce Colloque Médecine et Recherche réunit des experts du monde entier qui utilisent les techniques de genome editing pour répondre à des questions importantes en neuroscience, y compris en biologie fondamentale à partir de l’étude d’organismes modèles, ce qui peut permettre de mieux comprendre le fonctionnement et le développement du système nerveux, mais aussi contribuer à la compréhension et au traitement des troubles neurologiques chez l’homme. -

An Interview with Rudolf Jaenisch Andrea Aguilar*,‡

© 2015. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Development (2015) 142, 2085-2087 doi:10.1242/dev.126128 SPOTLIGHT An interview with Rudolf Jaenisch Andrea Aguilar*,‡ Rudolf Jaenisch is a Professor of Biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a founding member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research and the current president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR). His contributions to the stem cell field span from making the first transgenic mouse to seminal advances in the reprogramming field, and much more. In recognition of his pioneering research leading to induced pluripotency, he recently received the 2015 March of Dimes Prize in Developmental Biology. At the recent Keystone Meeting on ‘Transcriptional and Epigenetic Influences on Stem Cell States’ in Colorado, we had the opportunity to talk to him about his life and work. You initially studied medicine and then transitioned to basic research. What motivated or inspired you to make the change? My parents and grandparents were medical doctors so I was interested in studying medicine, although my father suggested I Hung Fan introduced me to the Moloney murine leukaemia virus shouldn’t. I actually liked going to medical school, especially the (MMLV) system, which I later used to generate transgenic mice. pre-clinical work: physiology, chemistry, anatomy and pathology. David Baltimore made a very significant contribution to my Then, in the 1960s, at the beginnings of molecular biology, I did my career too. My first contact with him was when he visited the Salk thesis on phages in Peter-Hans Hofschneider’s lab at the Max Institute.