The Origins of Oncomice: a History of the First Transgenic Mice Genetically Engineered to Develop Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Patentability of Synthetic Organisms

Creating Life from Scratch: The Patentability of Synthetic Organisms Michael Saunders* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 75 II. PATENTING MICROBIAL LIFE—CHAKRABARTY ................................ 77 III. PATENTING MULTICELLULAR LIFE—HARVARD ONCOMOUSE .......... 80 IV. IMPLICATIONS FOR SYNTHETIC BIOLOGY .......................................... 83 A. Single-Celled Synthetic Organisms ......................................... 83 B. Multicellular Synthetic Organisms .......................................... 86 V. CONCLUSIONS ..................................................................................... 88 I. INTRODUCTION Published in May 2007, U.S. application no. 20070122826 (Venter patent) describes a minimally operative genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma genitalium consisting of 381 genes, which the inventors believe to be essential for the survival of the bacterium in an environment containing all the necessary nutrients and free from stress.1 However, the team of inventors from the J. Craig Venter Institute is trying to accomplish something more than just the usual patenting of genes; they intend to create and patent the world’s first artificial organism. The team has already cleared two of the three major hurdles on its way to constructing this first synthetic organism. In January 2008, they announced completion of the second step, the laboratory synthesis of the entire 582,970 base pairs of the genome described in the patent above.2 What remains is the third and final step of inserting this human-made genome into a bacterial cell chassis and “booting up” the organism.3 Craig Venter and Hamilton Smith, lead researchers on the team have been discussing the creation of synthetic life since 1995, when their team published the first complete genome sequence of a living * © 2008 Michael Saunders. J.D. candidate 2009, Tulane University School of Law; B.S. 2003, Bucknell University. 1. -

10 Harvard Mouse

The Harvard Mouse or the transgenetic technique Term Paper Biology Georgina Cibula, 4e LIST of Contents Preface What is my motivation to work on the chosen topic? What is especially interesting? What are our questions with respects to the chosen topic? Introduction What is the context of the chosen topic? What is the recent scientific history? Where and why is the technique used? Are there alternatice treatments? Description of engineering technique No institution visited Discussion What progress was made with the application of the chosen technique? What future research steps? Ethical aspects Summary References PREFACE What is my motivation to work on the chosen topic? There are many reasons. One of them is that it’s a very interesting topic. It is fascinating, how you can increase or decrease the functionality of organisms. What is especially interesting? The intricacy. And that you can use the method not only for mice but for every organism. For example in the Green genetic engineering (to make plants more resistant) or for pharmaceuticals like human insulin. Some genes are responsible for the aging process. So if we can find those genes and deactivate them we would life longer. First successful experiments with animals where already made. What I also like about this topic is the big ethic question behind it. I mean in the end we use animals, often mice because of their similarity to our genes, to benefit of them. We intentional make them ill and lock them into small cages. But on the other hands medicaments can be tested or invented which can save many human lifes. -

Beatrice Mintz Date of Birth 24 January 1921 Place New York, NY (USA) Nomination 9 June 1986 Field Genetics Title Jack Schultz Chair in Basic Science

Beatrice Mintz Date of Birth 24 January 1921 Place New York, NY (USA) Nomination 9 June 1986 Field Genetics Title Jack Schultz Chair in Basic Science Professional address The Institute for Cancer Research Fox Chase Cancer Center 7701 Burholme Avenue, Room 215 Philadelphia, PA 19111 (USA) Most important awards, prizes and academies Awards: Bertner Foundation Award in Fundamental Cancer Research (1977); New York Academy of Sciences Award in Biological and Medical Sciences (1979); Papanicolaou Award for Scientific Achievement (1979); Lewis S. Rosenstiel Award in Basic Medical Research (1980); Genetics Society of America Medal (1981); Ernst Jung Gold Medal for Medicine (1990); John Scott Award for Scientific Achievement (1994); March of Dimes Prize in Developmental Biology (1996); American Cancer Society National Medal of Honor for Basic Research (1997); Pearl Meister Greengard Prize (2008); Albert Szent-Györgyi Prize for Progress in Cancer Research (2011). Academies: National Academy of Sciences (1973); Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science (1976); Honorary Fellow, American Gynecological and Obstetrical Society (1980); American Philosophical Society (1982); Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1982); Pontifical Academy of Sciences (1986). Degrees: Doctor of Science, New York Medical College (1980); Medical College of Pennsylvania (1980); Northwestern University (1982); Hunter College (1986); Doctor of Humane Letters, Holy Family College (1988). Summary of scientific research Beatrice Mintz discovered the underlying relationship between development and cancer. She first showed that development is based on an orderly hierarchical succession of increasingly specialized small groups of precursor or "stem" cells, expanding clonally. She proposed that cancer involves a regulatory aberration in this process, especially in the balance between proliferation and differentiation. -

Therapeutic Cloning Gives Silenced Genes a Second Voice

NEWS p1007 Tricky Fix: p1009 Bohemian p1010 Better than A vaccine for cocaine brain: Neuroscientist Prozac: What’s next in addiction poses John Hardy bucks antidepressant drug ethical dilemmas. the trends. development? Therapeutic cloning gives silenced genes a second voice As controversy continues on therapeutic experiments in Xenopus embryos, is the removal silencing may not be permanent.” cloning to create human embryos, applying the of methyl groups from specific regions of DNA. Jaenisch and his colleagues have also shown technique—also known as somatic cell nuclear This may be a necessary step in the epigenetic that nuclei from a skin cancer cell can be repro- transfer—in animals is generating important reprogramming of the nucleus, the researchers grammed to direct normal development of a insights into disease development. suggest in the October Nature Cell Biology. mouse embryo—meaning that removal of the Some scientists are using the approach to As cells differentiate, they accrue many epigenetic alterations is enough to restore cells study epigenetic alterations—chromosomal other types of epigenetic alterations, such as to normal (Genes Dev.18,1875–1885; 2004).An modifications that do not alter the DNA the addition of phosphates or removal of earlier study reported similar results with brain sequence—which can cause cancer. “A acetyl groups from histones, or chromosomal tumor cells (Cancer Res. 63, 2733–2736; 2003). principal question in cancer research is what proteins, and trigger changes in chromatin Based on such findings, pharmaceutical part of the cancer cell phenotype comes from structure. Defects in these processes have been companies are racing to develop and test ‘epige- genetic defects and what part is epigenetic,”says linked to cancer and other diseases. -

University-Industry Partnerships and the Licensing of the Harvard Mouse

PATENTS Managing innovation: university-industry partnerships and the licensing of the Harvard mouse Sasha Blaug1,Colleen Chien1 & Michael J Shuster DuPont’s Oncomouse patent licensing program continues to cause a stir in academia and industry. ver the last several decades, technology restructuring in the 1980s resulting in optimized for mutual near- and long-term Oand technological innovation have reduced industry R&D spending and scarcer benefits to the parties? Recently this dialog gradually replaced manufacturing and agri- federal R&D funding. Increased technology has been focused on DuPont’s licensing of culture as the main drivers of the US econ- transfer has sparked a debate on univ- the transgenic ‘Harvard mouse,’ subse- omy. The unparalleled system of American ersities’ roles in the national economy: on quently trademarked as the Oncomouse6. research universities1 and their association the extent to which these relationships affect http://www.nature.com/naturebiotechnology with industry are important drivers of the the mission of universities to carry out The Oncomouse patents new economy. The relationship between and disseminate the results of basic DuPont’s patent licensing program for universities and industry is multifaceted, research, and on how universities can man- ‘Oncomouse technology’ has caused a stir in encompassing exchanges of knowledge, age their partnerships, collaborations and academia and industry for over a decade7. expertise, working culture and money. technology transfer without compromising These patents broadly claim transgenic Whereas the transfer of technology from their mission. nonhuman mammals expressing cancer- universities to industry has been going on In the basic research paradigm, inves- promoting oncogenes, a basic research tool for more than a century, ties between uni- tigators’ inquiries are directed toward dev- widely used in the fight against cancer. -

Liberal Arts Science $600 Million in Support of Undergraduate Science Education

Janelia Update |||| Roger Tsien |||| Ask a Scientist SUMMER 2004 www.hhmi.org/bulletin LIBERAL ARTS SCIENCE In science and teaching— and preparing future investigators—liberal arts colleges earn an A+. C O N T E N T S Summer 2004 || Volume 17 Number 2 FEATURES 22 10 10 A Wellspring of Scientists [COVER STORY] When it comes to producing science Ph.D.s, liberal arts colleges are at the head of the class. By Christopher Connell 22 Cells Aglow Combining aesthetics with shrewd science, Roger Tsien found a bet- ter way to look at cells—and helped to revolutionize several scientif-ic disciplines. By Diana Steele 28 Night Science Like to take risks and tackle intractable problems? As construction motors on at Janelia Farm, the call is out for venturesome scientists with big research ideas. By Mary Beth Gardiner DEPARTMENTS 02 I N S T I T U T E N E W S HHMI Announces New 34 Investigator Competition | Undergraduate Science: $50 Million in New Grants 03 PRESIDENT’S LETTER The Scientific Apprenticeship U P F R O N T 04 New Discoveries Propel Stem Cell Research 06 Sleeper’s Hold on Science 08 Ask a Scientist 27 I N T E R V I E W Toward Détente on Stem Cell Research 33 G R A N T S Extending hhmi’s Global Outreach | Institute Awards Two Grants for Science Education Programs 34 INSTITUTE NEWS Bye-Bye Bio 101 NEWS & NOTES 36 Saving the Children 37 Six Antigens at a Time 38 The Emergence of Resistance 40 39 Hidden Potential 39 Remembering Santiago 40 Models and Mentors 41 Tracking the Transgenic Fly 42 Conduct Beyond Reproach 43 The 1918 Flu: Case Solved 44 HHMI LAB BOOK 46 N O T A B E N E 49 INSIDE HHMI Dollars and Sense ON THE COVER: Nancy H. -

Guide to Biotechnology 2008

guide to biotechnology 2008 research & development health bioethics innovate industrial & environmental food & agriculture biodefense Biotechnology Industry Organization 1201 Maryland Avenue, SW imagine Suite 900 Washington, DC 20024 intellectual property 202.962.9200 (phone) 202.488.6301 (fax) bio.org inform bio.org The Guide to Biotechnology is compiled by the Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) Editors Roxanna Guilford-Blake Debbie Strickland Contributors BIO Staff table of Contents Biotechnology: A Collection of Technologies 1 Regenerative Medicine ................................................. 36 What Is Biotechnology? .................................................. 1 Vaccines ....................................................................... 37 Cells and Biological Molecules ........................................ 1 Plant-Made Pharmaceuticals ........................................ 37 Therapeutic Development Overview .............................. 38 Biotechnology Industry Facts 2 Market Capitalization, 1994–2006 .................................. 3 Agricultural Production Applications 41 U.S. Biotech Industry Statistics: 1995–2006 ................... 3 Crop Biotechnology ...................................................... 41 U.S. Public Companies by Region, 2006 ........................ 4 Forest Biotechnology .................................................... 44 Total Financing, 1998–2007 (in billions of U.S. dollars) .... 4 Animal Biotechnology ................................................... 45 Biotech -

Changes in Expression of Putative Antigens Encoded by Pigment

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 92, pp. 10152-10156, October 1995 Medical Sciences Changes in expression of putative antigens encoded by pigment genes in mouse melanomas at different stages of malignant progression (albino locus/brown locus/slaty locus/silver locus) SETH J. ORLOW*, VINCENT J. HEARINGt, CHIE SAKAIt, KAZUNORI URABEt, BAO-KANG ZHOU*, WILLYS K. SILVERSt, AND BEATRICE MINTZO§ *Ronald 0. Perelman Department of Dermatology and Department of Cell Biology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY 10016; tLaboratory of Cell Biology, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; and tInstitute for Cancer Research, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA 19111 Contributed by Beatrice Mintz, July 25, 1995 ABSTRACT Cutaneous melanomas of Tyr-SV40E trans- This problem might be overcome by identifying changes in genic mice (mice whose transgene consists of the tyrosinase the antigenic profile associated with melanoma progression promotor fused to the coding regions of simian virus 40 early such that the design of a treatment protocol could encompass genes) strikingly resemble human melanomas in their devel- all the melanoma cells. Such a characterization in the case of opment and progression. Unlike human melanomas, the human melanoma would be complicated by genetic differences mouse tumors all arise in genetically identical individuals, among individuals, especially as the genetic background, as thereby better enabling expression of specific genes to be well as allelic differences at pigment gene loci themselves, can characterized in relation to advancing malignancy. The prod- influence the expression and interactions of these genes (11, ucts of pigment genes are of particular interest because 12). -

About Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research Selected

About Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research Selected Achievements in FOUNDING VISION Biomedical Science Whitehead Institute is a nonprofit, independent biomedical research institute with pioneering programs in cancer research, developmental biology, genetics, and Isolated the first tumor suppressor genomics. It was founded in 1982 through the generosity of Edwin C. "Jack" Whitehead, gene, the retinoblastoma gene, and a businessman and philanthropist who sought to create a new type of research created the first genetically defined institution, one that would exist outside the boundaries of a traditional academic human cancer cells. (Weinberg) institution, and yet, through a teaching affiliation with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), offer all the intellectual, collegial, and scientific benefits of a leading Isolated key genes involved in diabetes, research university. hypertension, leukemia, and obesity. (Lodish) WHITEHEAD INSTITUTE TODAY True to its founding vision, the Institute gives outstanding investigators broad freedom Mapped and cloned the male- to pursue new ideas, encourages novel collaborations among investigators, and determining Y chromosome, revealing a accelerates the path of scientific discovery. Research at Whitehead Institute is unique self-repair mechanism. (Page) conducted by 22 principal investigators (Members and Fellows) and approximately 300 visiting scientists, postdoctoral fellows, graduate students, and undergraduate Developed a method for genetically students from around the world. Whitehead Institute is affiliated with MIT in its engineering salt- and drought-tolerant teaching activities but wholly responsible for its own research programs, governance, plants. (Fink) and finance. Developed the first comprehensive cellular LEADERSHIP network describing how the yeast Whitehead Institute is guided by a distinguished Board of Directors, chaired by Sarah genome produces life. -

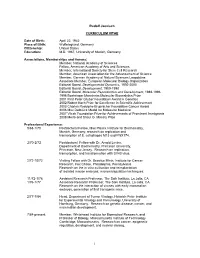

Rudolf Jaenisch

Rudolf Jaenisch CURRICULUM VITAE Date of Birth: April 22, 1942 Place of Birth: Wolfelsgrund, Germany Citizenship: United States Education: M.D. 1967, University of Munich, Germany Associations, Memberships and Honors: Member, National Academy of Sciences Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences Member, International Society for Stem Cell Research Member, American Association for the Advancement of Science Member, German Academy of Natural Sciences Leopoldina Associate Member, European Molecular Biology Organization Editorial Board, Developmental Dynamics, 1992-2000 Editorial Board, Development, 1989-1998 Editorial Board, Molecular Reproduction and Development, 1988-1996 1996 Boehringer Mannheim Molecular Bioanalytics Prize 2001 First Peter Gruber Foundation Award in Genetics 2002 Robert Koch Prize for Excellence in Scientific Achievement 2003 Charles Rodolphe Brupracher Foundation Cancer Award 2006 Max Delbrück Medal for Molecular Medicine 2007 Vilcek Foundation Prize for Achievements of Prominent Immigrants 2008 Meira and Shaul G. Massry Prize Professional Experience: 9/68-1/70 Postdoctoral Fellow, Max Planck Institute for Biochemistry, Munich, Germany; research on replication and transcription of E. coli phages M13 and PhiX174. 2/70-2/72 Postdoctoral Fellow with Dr. Arnold Levine, Department of Biochemistry, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey. Research on replication, transcription, and transformation with SV40 virus. 2/72-10/72 Visiting Fellow with Dr. Beatrice Mintz, Institute for Cancer Research, Fox Chase, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Research on the in vitro cultivation and reimplantation of isolated mouse embryos; micromanipulation techniques. 11/72-1/76 Assistant Research Professor, The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA 1/76-1/77 Associate Research Professor, The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA Research on the interaction of viruses with early mammalian embryos, generation of first transgenic mice. -

A Comprehensive Analysis of Sexual Dimorphism in the Midbrain Dopamine System

A comprehensive analysis of sexual dimorphism in the midbrain dopamine system Amanda Shinae Zila A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Larry S. Zweifel (Chair) Richard D. Palmiter Paul E. M. Phillips Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Pharmacology 1 ©Copyright 2016 Amanda Shinae Zila 2 University of Washington Abstract A comprehensive analysis of sexual dimorphism in the midbrain dopamine system Amanda Shinae Zila Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Assistant Professor Larry S. Zweifel Department of Pharmacology The dopamine system is widely thought to play a role in many crucial behaviors, including reward association, motivation, and addiction. Additionally, dopamine is also linked to multiple diseases, such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, and autism. What is striking about these diseases is they present with sex differences in multiple aspects including susceptibility, progression, and response to treatment. However, we know very little about sex differences in the dopamine system, especially at a baseline state. In the current study, I provided a comprehensive analysis of the dopamine system in males and females, including circuitry, physiology, gene expression, and behavior. Employing retrograde viral tools, we characterized the inputs to the entire ventral tegmental area (VTA), to VTA dopamine neurons specifically, and compared the number of GABAergic, glutamatergic, and serotonergic inputs to the VTA; we also mapped VTA dopaminergic outputs through use of excitatory DREADDs. However, a comparison of the number of inputs in each brain area between males and females revealed no differences. An interesting discovery was the high amount of GABAergic inputs to the VTA, relative to 3 glutamatergic and serotonergic. -

The Supreme Court of Canada First Wrestled with the Patentability Of

SCHMEISERV. MONSANTO 553 SCHMEISER V. MONSANTO: A CASE COMMENT EDWARD (TED) Y00 AND ROBERT BOTHWELL• I. INTRODUCTION The SupremeCourt of Canada first wrestledwith the patentabilityof higher life forms in the Harvard mouse case.1 Their decision to refuse patents claiming genetically modified animals, and by extensionplants, was a major disappointmentto many in the biotechnology industryin Canada. Canadastood alone amongstits GS partnersas the onejurisdiction where such patents could not be obtained. Dire predictions about the future of biotechnology research and developmentin Canada were made. Whenthe SupremeCourt granted leave to appeal2to Mr. Schmeiserin his legal battle with industry giant Monsanto, it was thought by many that the rights of patentees could take another blow, and further set back Canada's growing biotech industry. Others more optimisticallybelieved that the SupremeCourt had an opportunityto expand patent rights in the biotech field. 2004 CanLIIDocs 149 II. FACTS The respondents, Monsanto Company and Monsanto Canada Inc., are the owner and Iicensee respectively of a patent titled"G lyphosate-ResistantPlants." The patent was granted in 1993 and is directed to a chimeric3 gene that confers upon canola plants resistance to glyphosate-basedherbicides. The resulting plant is named "Roundup Ready Canola" by Monsanto, referring to the resistance demonstrated by the modified canola plant towards Monsanto'sown glyphosate-basedherbicide "Roundup." Monsanto licenses its Roundup Ready Canola to farmers for a fee, provided they sign a Technology Use Agreement(TUA), which entitles the farmer to purchase Roundup Ready Canola from an authorized Monsanto agent. The TUA restricts the farmer from using the seed to plant more than one crop and requires the crop to be sold only for consumptionto a commercialpurchaser authorized by Monsanto.The farmer is also prohibited from selling or givingthe seed to a third party.