The Patentability of Synthetic Organisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BANARAS LAW JOURNAL [Vol

2014 1 THE BANARAS LAW JOURNAL 2 THE BANARAS LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 43] Cite This Issue as Vol. 43 No. 1 Ban.L.J. (2014) The Banaras Law Journal is published bi-annually by the Faculty of Law, Banaras Hindu University since 1965.Articles and other contributions for possible publication are welcomed and these as well as books for review should be addressed to the Editor-in-Chief, Banaras Law Journal, Faculty of Law, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi - 221005, India, or e-mailed to <[email protected]>. Views expressed in the Articles, Notes & Comments, Book Reviews and all other contributions published in this Journal are those of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Editors of the Banaras Law Journal. In spite of our best care and caution, errors and omissions may creep in, for which our patrons will please bear with us and any discrepancy noticed may kindly be brought to our knowlede which will improve our Journal. Further it is to be noted that the Journal is published with the understanding that Authors, Editors, Printers and Publishers are not responsible for any damages or loss accruing to any body. In exchange for Banaras Law Journal, the Law School, Banaras Hindu University would appreciate receiving Journals, Books and monographs, etc. which can be of interest to Indian specialists and readers. c Law School, B.H.U., Varanasi- 221005 Composed and Printed by Raj Kumar Jaiswal, Dee Gee Printers, Khojwan Bazar, Varanasi-221010, U.P., (India). 2014 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE 3 Prof. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 – 14 One Hundred and Fifth Year Indian Institute of Science Bangalore - 560 012 i ii Contents Page No Page No Preface 5.3 Departmental Seminars and IISc at a glance Colloquia 120 5.4 Visitors 120 1. The Institute 1-3 5.5 Faculty: Other Professional 1.1 Court 1 Services 121 1.2 Council 2 5.6 Outreach 121 1.3 Finance Committee 3 5.7 International Relations Cell 121 1.4 Senate 3 1.5 Faculties 3 6. Continuing Education 123-124 2. Staff 4-18 7. Sponsored Research, Scientific & 2.1 Listing 4 Industrial Consultancy 125-164 2.2 Changes 12 7.1 Centre for Sponsored Schemes 2.3 Awards/Distinctions 12 & Projects 125 7.2 Centre for Scientific & Industrial 3. Students 19-25 Consultancy 155 3.1 Admissions & On Roll 19 7.3 Intellectual Property Cell 162 3.2 SC/ST Students 19 7.4 Society for Innovation & 3.3 Scholarships/Fellowships 19 Development 163 3.4 Assistance Programme 19 7.5 Advanced Bio-residue Energy 3.5 Students Council 19 Technologies Society 164 3.6 Hostels 19 3.7 Award of Medals 19 8. Central Facilities 165-168 3.8 Placement 21 8.1 Infrastructure - Buildings 165 8.2 Activities 166 4. Research and Teaching 26-116 8.2.1 Official Language Unit 166 4.1 Research Highlights 26 8.2.2 SC/ST Cell 166 4.1.1 Biological Sciences 26 8.2.3 Counselling and Support Centre 167 4.1.2 Chemical Sciences 35 8.3 Women’s Cell 167 4.1.3 Electrical Sciences 46 8.4 Public Information Office 167 4.1.4 Mechanical Sciences 57 8.5 Alumni Association 167 4.1.5 Physical & Mathematical Sciences 75 8.6 Professional Societies 168 4.1.6 Centres under Director 91 4.2. -

10 Harvard Mouse

The Harvard Mouse or the transgenetic technique Term Paper Biology Georgina Cibula, 4e LIST of Contents Preface What is my motivation to work on the chosen topic? What is especially interesting? What are our questions with respects to the chosen topic? Introduction What is the context of the chosen topic? What is the recent scientific history? Where and why is the technique used? Are there alternatice treatments? Description of engineering technique No institution visited Discussion What progress was made with the application of the chosen technique? What future research steps? Ethical aspects Summary References PREFACE What is my motivation to work on the chosen topic? There are many reasons. One of them is that it’s a very interesting topic. It is fascinating, how you can increase or decrease the functionality of organisms. What is especially interesting? The intricacy. And that you can use the method not only for mice but for every organism. For example in the Green genetic engineering (to make plants more resistant) or for pharmaceuticals like human insulin. Some genes are responsible for the aging process. So if we can find those genes and deactivate them we would life longer. First successful experiments with animals where already made. What I also like about this topic is the big ethic question behind it. I mean in the end we use animals, often mice because of their similarity to our genes, to benefit of them. We intentional make them ill and lock them into small cages. But on the other hands medicaments can be tested or invented which can save many human lifes. -

University-Industry Partnerships and the Licensing of the Harvard Mouse

PATENTS Managing innovation: university-industry partnerships and the licensing of the Harvard mouse Sasha Blaug1,Colleen Chien1 & Michael J Shuster DuPont’s Oncomouse patent licensing program continues to cause a stir in academia and industry. ver the last several decades, technology restructuring in the 1980s resulting in optimized for mutual near- and long-term Oand technological innovation have reduced industry R&D spending and scarcer benefits to the parties? Recently this dialog gradually replaced manufacturing and agri- federal R&D funding. Increased technology has been focused on DuPont’s licensing of culture as the main drivers of the US econ- transfer has sparked a debate on univ- the transgenic ‘Harvard mouse,’ subse- omy. The unparalleled system of American ersities’ roles in the national economy: on quently trademarked as the Oncomouse6. research universities1 and their association the extent to which these relationships affect http://www.nature.com/naturebiotechnology with industry are important drivers of the the mission of universities to carry out The Oncomouse patents new economy. The relationship between and disseminate the results of basic DuPont’s patent licensing program for universities and industry is multifaceted, research, and on how universities can man- ‘Oncomouse technology’ has caused a stir in encompassing exchanges of knowledge, age their partnerships, collaborations and academia and industry for over a decade7. expertise, working culture and money. technology transfer without compromising These patents broadly claim transgenic Whereas the transfer of technology from their mission. nonhuman mammals expressing cancer- universities to industry has been going on In the basic research paradigm, inves- promoting oncogenes, a basic research tool for more than a century, ties between uni- tigators’ inquiries are directed toward dev- widely used in the fight against cancer. -

Guide to Biotechnology 2008

guide to biotechnology 2008 research & development health bioethics innovate industrial & environmental food & agriculture biodefense Biotechnology Industry Organization 1201 Maryland Avenue, SW imagine Suite 900 Washington, DC 20024 intellectual property 202.962.9200 (phone) 202.488.6301 (fax) bio.org inform bio.org The Guide to Biotechnology is compiled by the Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) Editors Roxanna Guilford-Blake Debbie Strickland Contributors BIO Staff table of Contents Biotechnology: A Collection of Technologies 1 Regenerative Medicine ................................................. 36 What Is Biotechnology? .................................................. 1 Vaccines ....................................................................... 37 Cells and Biological Molecules ........................................ 1 Plant-Made Pharmaceuticals ........................................ 37 Therapeutic Development Overview .............................. 38 Biotechnology Industry Facts 2 Market Capitalization, 1994–2006 .................................. 3 Agricultural Production Applications 41 U.S. Biotech Industry Statistics: 1995–2006 ................... 3 Crop Biotechnology ...................................................... 41 U.S. Public Companies by Region, 2006 ........................ 4 Forest Biotechnology .................................................... 44 Total Financing, 1998–2007 (in billions of U.S. dollars) .... 4 Animal Biotechnology ................................................... 45 Biotech -

The Supreme Court of Canada First Wrestled with the Patentability Of

SCHMEISERV. MONSANTO 553 SCHMEISER V. MONSANTO: A CASE COMMENT EDWARD (TED) Y00 AND ROBERT BOTHWELL• I. INTRODUCTION The SupremeCourt of Canada first wrestledwith the patentabilityof higher life forms in the Harvard mouse case.1 Their decision to refuse patents claiming genetically modified animals, and by extensionplants, was a major disappointmentto many in the biotechnology industryin Canada. Canadastood alone amongstits GS partnersas the onejurisdiction where such patents could not be obtained. Dire predictions about the future of biotechnology research and developmentin Canada were made. Whenthe SupremeCourt granted leave to appeal2to Mr. Schmeiserin his legal battle with industry giant Monsanto, it was thought by many that the rights of patentees could take another blow, and further set back Canada's growing biotech industry. Others more optimisticallybelieved that the SupremeCourt had an opportunityto expand patent rights in the biotech field. 2004 CanLIIDocs 149 II. FACTS The respondents, Monsanto Company and Monsanto Canada Inc., are the owner and Iicensee respectively of a patent titled"G lyphosate-ResistantPlants." The patent was granted in 1993 and is directed to a chimeric3 gene that confers upon canola plants resistance to glyphosate-basedherbicides. The resulting plant is named "Roundup Ready Canola" by Monsanto, referring to the resistance demonstrated by the modified canola plant towards Monsanto'sown glyphosate-basedherbicide "Roundup." Monsanto licenses its Roundup Ready Canola to farmers for a fee, provided they sign a Technology Use Agreement(TUA), which entitles the farmer to purchase Roundup Ready Canola from an authorized Monsanto agent. The TUA restricts the farmer from using the seed to plant more than one crop and requires the crop to be sold only for consumptionto a commercialpurchaser authorized by Monsanto.The farmer is also prohibited from selling or givingthe seed to a third party. -

Maurice Wilkins Page...28 Satellite Radio in Different Parts of the Country

CMYK Job No. ISSN : 0972-169X Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers of India: R.N. 70269/98 Postal Registration No. : DL-11360/2002 Monthly Newsletter of Vigyan Prasar February 2003 Vol. 5 No. 5 VP News Inside S&T Popularization Through Satellite Radio Editorial ith an aim to utilize the satellite radio for science and technology popularization, q Fifty years of the Double Helix W Vigyan Prasar has been organizing live demonstrations using the WorldSpace digital Page...42 satellite radio system for the benefit of school students and teachers in various parts of the ❑ 25 Years of In - Vitro Fertilization country. To start with, live demonstrations were organized in Delhi in May 2002. As an Page...37 ongoing exercise, similar demonstrations have been organized recently in the schools of ❑ Francis H C Crick and Bangalore (7 to 10 January,2003) and Chennai (7 to 14 January,2003). The main objective James D Watson Page...34 is to introduce teachers and students to the power of digital satellite transmission. An effort is being made to network various schools and the VIPNET science clubs through ❑ Maurice Wilkins Page...28 satellite radio in different parts of the country. The demonstration programme included a brief introduction to Vigyan Prasar and the ❑ Rosalind Elsie Franklin Satellite Digital Broadcast technology, followed by a Lecture on “Emerging Trends in Page...27 Communication Technology” by Prof. V.S. Ramamurthy, Secretary, Department of Science ❑ Recent Developments in Science & Technology and Technology and Chairman, Governing Body of VP. Duration of the Demonstration Page...29 programme was one hour, which included audio and a synchronized slide show. -

Vol. 68, No. 2: Full Issue

Denver Law Review Volume 68 Issue 2 Symposium - Intellectual Property Law Article 13 February 2021 Vol. 68, no. 2: Full Issue Denver University Law Review Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Denver University Law Review, Vol. 68, no. 2: Full Issue, 68 Denv. U. L. Rev. (1991). This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Denver Law Review at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. DENVER UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 68 1991 Published by the University of Denver DENVER College of Law UNIVERSITY LAW 1991 Volume 68 Issue 2 REVIEW TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword Dedication In Honor of Christopher H. Munch ARTICLES Introduction Donald S. Chisum 119 Biotechnology Patent Law: Perspective of the First Seventeen Years, Prospective on the Next Seventeen Years Lorance L. Greenlee 127 Property Rights in Living Matter: Is New Law Required? Robert L. Baechtold 141 Lawrence S. Perry, Jennifer A. Tegfeldt Patricia Carson and Peter Knudsen The Biotechnology Patent Protection Act David Beier 173 and Robert H. Benson A Proposed Legal Advisor's Roadmap for Software Developers John T. Soma, Robert D. Sprague 191 M. Susan Lombardi and Carolyn M. Lindh Requirements for Deposits of Biological Materials for Patents Worldwide Thomas D. Denberg 229 and Ellen P. Winner The En Banc Rehearing of In re Dillon: Policy Considerations and Implications for Patent Prosecution Margaret]W4.Wall 261 and Justi,n Dituri The Effect of "Incontestability" in Trademark Litigation Joan L Dillon 277 File Wrapper Estoppel and the Federal Circuit Glenn K Beaton 283 COMMENT Steward v. -

International Conference of the Council of Europe on Ethical Issues Arising from the Application of Biotechnology

International Conference of the Council of Europe on Ethical Issues Arising from the Application of Biotechnology Oviedo (Spain), 16-19 May 1999 PROCEEDINGS Part 1: General introduction Reports of sessions General report TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ......................................................................................................................... page 5 Programme of the Conference.......................................................................................... page 7 General Introduction Prof. Jean-François MATTEI (France / Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe)................................................................................................ page 11 Report on the Environment session Dr Piet VAN DER MEER (The Netherlands).................................................................. page 19 Report on the Food session Dr George ZERVAKIS (Greece) ..................................................................................... page 27 Report on the Human Health session M. Joze V. TRONTELJ (Slovenia) and Sir Dai REES (European Science Foundation)........................................................ page 33 Report on the Animal Welfare session Dr Paul DE GREEVE (The Netherlands) ....................................................................... page 39 Report on the Research session Dr Hans-Jörg BUHK (Germany).................................................................................... page 43 Report on the Industry session Dr Monika MÖRTBERG-BACKLUND (Sweden) .......................................................... -

TEST BIOTECH Testbiotech E

1 | Stop investment in animal suffering | TEST BIOTECH Testbiotech e. V. Institut für unabhängige Folgenabschätzung in der Biotechnologie Picture: Testbiotech / Falk Heller/ Argum “Stop investment in animal suffering“ Patents on animals and new methods in genetic engineering: Economic interests leading to an increasing number of animal experiments Christoph Then for Testbiotech, June 2015 Supported by: “Stop investment in animal suffering” Patents on animals and new methods in genetic engineering: Economic interests leading to an increasing number of animal experiments Christoph Then for Testbiotech, June 2015 Testbiotech Institute for Independent Impact Assessment of Biotechnology Frohschammerstr. 14 D-80807 Munich Tel.: +49 (0) 89 358 992 76 Fax: +49 (0) 89 359 66 22 [email protected] www.testbiotech.org Executive Director: Dr Christoph Then Contents Summary 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Patents on animals 6 Who is filing patents on animals? 7 Grounds for granting European patents 8 Patents are driving the increasing number of animal experiments 8 3. New methods in genetic engineering 11 Synthetic gene technologies 11 Profitable markets for genetically engineered animals 13 4. Patents on genetically engineered chimpanzees 15 Case study 1: Patent held by Altor Bioscience 15 Case study 2: The patent held by Bionomics 17 Case study 3: Patents held by Intrexon 18 5. Politics, industry and investors have to take responsibility 20 6. Conclusions 21 References 22 4 | Stop investment in animal suffering | Summary Summary This report shows how the rising number of experiments carried out on genetically engineered animals is linked to economic interests. It reveals an increasing number of genetically engineered animals coming onto the market as “animal models”, and how patents on animals create additional incentives for invest- ment into animal suffering for monetary gain. -

A Feasibility Study of Oncogene Transgenic Mice As Therapeutic Models in Cytokine Research

A feasibility study of oncogene transgenic mice as therapeutic models in cytokine research Hilary Thomas A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London September 1996 Imperial Cancer Research Fund 44 Lincoln's Inn Fields London WC2A3PX ProQuest Number: 10055883 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10055883 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract Transgenic mice carrying the activated rat c-neu oncogene under transcriptional control of the MMTV promoter were backcrossed to BALB/c mice, with the aim of developing a model for cancer therapy. A total of 86 of 268 transgene positive mice in the first five generations developed 93 histologically diverse tumours (median age of onset 18 months). The cumulative incidence of breast tumours at 24 months was 18%, and overall tumour incidence 31%. As well as expected c-neii expressing breast cancers, lymphomas and Harderian gland carcinomas developed. All of the mammary carcinomas, Harderian gland carcinomas and lymphomas expressed c-erb B2. Virgin mice had fewer mammary tumours than those with two litters (p= 0.006), further litters did not affect tumour incidence. -

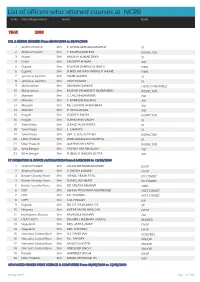

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT.