Comparative Analysis of Privilege in Relation to the School District of Philadelphia and the Tredyffrin-Easttown School District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kelly R. Quinn Pre-K

2559 Crum Creek Drive (610) 620-4216 Berwyn, Pennsylvania 19312 [email protected] Kelly R. Quinn Pre-K – 4th Grade Teacher Education 2010- 2014 West Chester University of Pennsylvania - West Chester, PA Bachelor of Science in Education GPA: 3.448 Major: Early Grades Preparation PreK- 4 Dean’s List - College of Education - 5 consecutive semesters Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Teacher’s Certification June 2014 2017- present West Chester University- West Chester, PA Masters: Special Education Postbaccalaureate: Special Education 2006-2010 Conestoga High School - Berwyn, PA Varsity track team Child Development preparatory classes - 2008-2010 Educational and Coaching Pre-Service Experience 08/2016- Present Universal of Daroff Charter School- Second Grade Teacher- Philadelphia, PA -Set up two field trips: Education Day at Villanova University and Philadelphia Zoo 06/2017- Present- Episcopal Academy- K Assistant Teacher- Berwyn, PA 11/2016- Present- Saint Norbert’s School- 7/ 8th Grade Varsity Girls Basketball Coach- Berwyn, PA 10/2015- 10/2016 Marple Newtown High School- Basketball Coach- Newtown Square,PA 08/2015-Present Malvern Prep- Soccer JV Assistant Coach- Malvern, PA 10/2015-Present Tredyffrin/Easttown School District- Berwyn, PA- Substitute Teacher 5/2016-08/2016 Chestnutwold Elementary School- Ardmore, PA –Building Substitute Kindergarten- fifth grade 10/2014- 05/2016 Chestnutwold Elementary School- Ardmore, PA- Instructional Assistant- Second- Fourth Grade 01/2014- 06/2014 Kindergarten Center - Drexel Hill, PA – Student Teaching -

Coatesville Area School District and Wells Fargo Had with the University

COATESVILLE AREA SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL 1445 East Lincoln Highway, Coatesville, PA 19320 11/12 Center - Phone (610) 383-3730 Michele Snyder, Principal Jeff Colf, Assistant Principal Linda Giles, Interim Assistant Principal Matthew McCain, Director of Activities, Athletics, and Compliance April 15, 2019 Good Morning Parents and Guardians, It is hard to believe that Spring Break is just around the corner. As a reminder, parents, remember that students are in school on Wednesday, April 17 for a snow make up day. Students are off beginning Thursday, April 18. Students return to school on Tuesday, April 23. This year is certainly moving quickly and will soon be at a close. This time of the year is always extremely busy, with many events and activities. Please try to attend one of our upcoming spring concerts, stop by and cheer on one of our spring sports teams or come out to our Prom Parade to participate in one of our many time-honored traditions. Congratulations to Dr. Giles, Miss Gabby Hines, the Musical Director and the cast, pit orchestra members and the crew of our musical, “Willy Wonka”. Also, a big thank you to our Art Department for their assistance on the set design. The production was outstanding. It was wonderful to see so many future high school students filling supporting roles in our cast. What a wonderful community event. Thank you, parents and community, for your continued support of performing arts at the high school. On Thursday, April 11, several of our students were invited to West Chester University to celebrate the three-year partnership that the Coatesville Area School District and Wells Fargo had with the University. -

Pennsylvania

2019 RECOGNIZING EXCELLENCE IN THE ART AND LITERARY MAGAZINES PENNSYLVANIA REALM First Class Gettysburg High School Gettysburg, PA Interrobang Faculty Advisor: Lisanne Bales Student Editor(s): Mackenzie Monn, Julia Morgan Penncrest High School Media, PA Gryphon Faculty Advisor: Jim Zervanos Student Editor(s): Kiersten Busch, Katie Merillat, Emily Nolen Upper Dublin High School Fort Washington, PA Rhapsody Faculty Advisor: Kimberly Stern Student Editor(s): Connie Liu, Lauren Li, Belinda Jin, Robert Frazier, Emma Yoon, Anna Zhou Wyoming Valley West High School Plymouth, PA Interim Faculty Advisor: Karin Ulitchney Student Editor(s): Rhenalee Lauver, Hannah Leary, Shelly Duran, Eleanor Punko Superior Conestoga High School Berwyn, PA The Folio Faculty Advisor: Ben Smith Student Editor(s): Gabi Miko, Laila Norford, Laura Liu, Alexandra Ross Jim Thorpe Area High School Jim Thorpe, PA The Flame Faculty Advisor: Trudy Miller Student Editor(s): Natalia Richards, Sydney McArdle Excellent Andrew W. Mellon Middle School Pittsburgh, PA The Outlook Faculty Advisor: Eve Kollar Student Editor(s): Abby Atkinson, Gina Malachow, Sydney Martin, Brynn Murawski, Lily Stern, Amanda Stein, Kathy Vo Bishop McDevitt High School Harrisburg, PA The Fallout Shelter Faculty Advisor: Josh Yeckley Student Editor(s): Samantha Knipple, Gillian Gurney, Wallis Chen, Alexandra McInerney, Hannah O’Dea, Joshua Po Chambersburg Area Senior High School Chambersburg, PA CASHS Collections Faculty Advisor: Christine Rose Brooks Student Editor(s): Julianne Grove, Taylor Pearce, Carly -

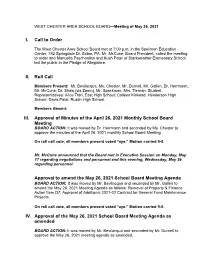

I. Call to Order II. Roll Call III. Approval

WEST CHESTER AREA SCHOOL BOARD—Meeting of May 26, 2021 I. Call to Order The West Chester Area School Board met at 7:00 p.m. in the Spellman Education Center, 782 Springdale Dr. Exton, PA. Mr. McCune, Board President, called the meeting to order and Manuella Paschoalino and Kush Patel of Starkweather Elementary School led the public in the Pledge of Allegiance. II. Roll Call Members Present: Mr. Bevilacqua, Ms. Chester, Mr. Durnell, Mr. Gallen, Dr. Herrmann, Mr. McCune, Dr. Shaw (via Zoom), Mr. Spackman, Mrs. Tiernan. Student Representatives: Alice Tran, East High School; Colleen Kinkead, Henderson High School; Davis Patel, Rustin High School. Members Absent: III. Approval of Minutes of the April 26, 2021 Monthly School Board Meeting BOARD ACTION: It was moved by Dr. Herrmann and seconded by Ms. Chester to approve the minutes of the April 26, 2021 monthly School Board Meeting. On roll call vote, all members present voted “aye.” Motion carried 9-0. Mr. McCune announced that the Board met in Executive Session on Monday, May 17 regarding negotiations and personnel and this evening, Wednesday, May 26 regarding personnel. Approval to amend the May 26, 2021 School Board Meeting Agenda BOARD ACTION: It was moved by Mr. Bevilacqua and seconded by Mr. Gallen to amend the May 26, 2021 Meeting Agenda as follows: Removal of Property & Finance Action Item D7: Approval of Additional 2021-22 Contract for General Fund Maintenance Projects. On roll call vote, all members present voted “aye.” Motion carried 9-0. IV. Approval of the May 26, 2021 School Board Meeting Agenda as amended BOARD ACTION: It was moved by Mr. -

Directions to Other Schools

TO: Pottstown Fans Due to the requests for directions to schools from parents and dedicated Pottstown fans, we have compiled this booklet from our direction file. Please take into consideration that the number of traffic lights and landmarks may have changed over the years, and we would appreciate if you would contact our office (484-941-9842) if directions are incorrect or not clear. You can also get directions to schools by using the athletic schedule feature on the school web page on the Activities link. Thank you. Pat Connors, Director of Co-Curricular Activities ABINGTON HIGH SCHOOL, Highland Avenue, Abington, PA Take PA Turnpike East to Willow Grove Exit No. 27 Get off turnpike and take Rt. 611 South (Easton Road & then Old York Road) Follow Rt. 611 South into Willow Grove (Rt. 611 will bear left past Burger King) * st Stay on Rt. 611 past Boston Market to 1 Street after overpass- Jerico Road -Turn right (Fitzpatrick Funeral Home) Follow Jerico Road directly into Abington Junior/Senior High School Campus Bear to right around high school - Field House (dome shape) is in the back of school. FOOTBALL STADIUM: Continue from * Stay on Route 611 (Old York Road) to Susquehanna Road. There is a First Union Bank on left corner. Make a left onto Susquehanna Road, then past Retirement Community Apartment to the next road – Huntingdon Road. Make a left onto Huntington Road and Memorial park (football stadium) will be on your right. Stadium is on the corner of Susquehanna & Huntingdon. (Approximate travel time – 50 minutes from Spring-Ford.) ACADEMY PARK HIGH SCHOOL, 300 Calcon Hook Road, Sharon Hill, PA 19079 Route 422 Bypass East to Route 202 North to Route 76 East (Schuylkill Expressway), to Route 476 South (Blue Route) to I- 95 North. -

Fiscal Year 2011-2012

Chester County Food Bank ANNUAL REPORT 2011-2012 DOING MORE | A Message from our Board Chairman As we reflect on the past year, it becomes obvious that we are making tremendous strides in alleviating hunger in our communities. All of our “numbers” are up. We distributed more than 1.7 million pounds of food and greatly increased the fresh food that we grew and purchased at auction to over 500,000 pounds. We are providing food to more food cupboards and meal sites than ever before. Our Raised Bed Gardens are now over 400 and in 22 schools and we were able to double the participants in our Food Backpack program to 903 students. But we are more than numbers. Each area of growth represents more families who no longer have to struggle with hunger… more children who can enjoy their childhood free from strife. Thanks to our friends in the community, we are able to do more. Our corporate sponsors have re- sponded to our needs with donations, food drives, and volunteers. The support of our donors has allowed us to expand our programs, add a full-time food manager, second driver, and community outreach person. This growth has been possible as a result of a dedicated Board, strong management, a caring community, and an ever increasing support of volunteers. Many, many thanks to all! Robert McNeil Board Chairman WORKING TOGETHER | A Message from our Executive Director The Chester County Food Bank moves into its fourth year of operation continuing its dedication to finding new ways to meet the needs of the thousands we serve. -

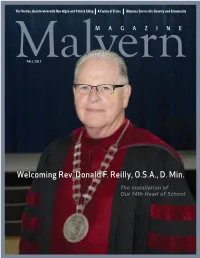

Welcoming Rev. Donald F. Reilly, O.S.A., D. Min

The Veritas: An Interview with Ron Algeo and Patrick Sillup A Family of Friars Alumnus Serves His Country and Community FALL 2017 Welcoming Rev. Donald F. Reilly, O.S.A., D. Min. The Installation of Our 14th Head of School EXPERIENCE MALVERN PREP THIS WINTER LEARN MORE ABOUT HOW YOUR UPCOMING EVENTS SON WILL SUCCEED WITH THE PREVIEW MORNING EDUCATION WE OFFER THURSDAY, Enjoy a student guided tour of our campus, find out how our student-led classrooms will help shape your DECEMBER 7 son’s experience. You’ll also gain the opportunity to 8:30 - 11:00 a.m. chat with students and faculty, having all of your questions answered... See you there! ENTRANCE EXAMS SATURDAY, BE SURE TO DECEMBER 2 REGISTER TODAY! & FEBRUARY 3 8:00 - 12:00 noon www.malvernprep.org/admissions or reply to [email protected] UNABLE TO ATTEND? Contact us to schedule a personal tour: Malvern Preparatory School is a private, independent, 484-595-1173 Catholic school for boys in grades 6-12. www.malvernprep.org 418 SOUTH WARREN AVENUE | MALVERN, PENNSYLVANIA 19355 | WWW.MALVERNPREP.ORG Admissions_FullPage.indd 1 11/20/2017 3:12:43 PM Contents MALVERN MAGAZINE :: VOLUME 15 :: ISSUE 1 :: FALL 2017 FEATURES 12 THE INSTALLATION OF REV. DONALD F. REILLY, O.S.A., D. MIN. In October Fr. Reilly was officially installed as Malvern Prep's 14th Head of School. We share images from the Mass and Installation ceremonies and also provide background on Fr. Reilly, his childhood, and career leading to his new position at Malvern. BY ALLISON HALL 22 THE VERITAS: AN INTERVIEW WITH RON ALGEO AND PATRICK SILLUP Mr. -

Chester County Academic Competition

CHESTER COUNTY ACADEMIC COMPETITION Now in its 34th year, the Chester County Academic Competition provides an opportunity for students from twenty-four high schools to compete in a “college-bowl” format where students answer a wide variety of challenging questions from a variety of categories including literature, math, science, American and world history, geography, and contemporary events. All teams will compete in the semifinal matches, seeded based upon their performance in the 17/18 season. The three teams winning teams from the semifinal matches will then compete in the championship match. The Chester County champion will represent the Chester County Intermediate Unit in the Pennsylvania Academic Competition which will take place on the floors of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and the Senate in Harrisburg, PA. Every attempt is made to ensure the fairness and accuracy of each competition; however, competitions are unpredictable. As such, any determination made by academic competition staff will be final. MISSION STATEMENT It is the mission of Chester County Academic Competition to promote lifelong learning, celebrate academic achievement and enhance self-confidence as members of a team by providing healthy yet challenging opportunities for high school students to develop both academic, social and personal skills. v. 09.20.16 SCHOOL COACH PRINCIPAL SUPERINTENDENT Avon Grove CS Michael Mostello Blase Maitland Kristen Bishop Lauren Daniel Avon Grove HS Amanda Cahill Scott DeShong Dr. Christopher Marchese Jenna Kravel Bayard Rustin HS Robyn Melbourne Dr. Michael A. Marano Dr. James Scanlon Amy Chessock Bishop Shanahan HS Paul Finley Michael McArdle Sr. Maureen Lawrence McDermott David McQuiston Mary Jane Ansley Coatesville Sr. -

District I Abbreviations and Short Names

District I Abbreviations and Short Names Abbr School Short Name Abbr School Short Name AB Abington High School Abington MSJ Mount Saint Joseph Academy Mount St Joseph AP Academy Park High School Academy Park NAZ Nazareth Academy High School Nazareth AG Avon Grove High School Avon Grove NES Neshaminy High School Neshaminy BEN Bensalem High School Bensalem NHS New Hope-Solebury High School New Hope Sole BS Bishop Shanahan High School Shanahan NOR Norristown Area High School Norristown BOY Boyertown Area High School Boyertown NP North Penn High School North Penn BRI Bristol High School Bristol OCT Octorara Area High School Octorara CCA Calvary Christian Academy Calvary OJR Owen J Roberts High School O J Roberts CBE Central Bucks East High School CB East OX Oxford Area High School Oxford CBS Central Bucks South High School CB South PNW Penn Wood High School Penn Wood CBW Central Bucks West High School CB West PNC Penncrest High School Penncrest CHH Cheltenham High School Cheltenham PNR Pennridge High School Pennridge CHE Chester High School Chester PNB Pennsbury High School Pennsbury CHC Chichester High School Chichester PV Perkiomen Valley High School Perk Valley CDM Christopher Dock Mennonite HS Dock PHV Phoenixville Area High School Phoenixville CV Coatesville Area High School Coatesville PCS Plumstead Christian School Plumstead CON Conestoga High School Conestoga PW Plymouth Whitemarsh High School Ply Whitemarsh CRS Council Rock South High School CR South PJP Pope John Paul II High School Pope John Paul CRN Council Rock North High School -

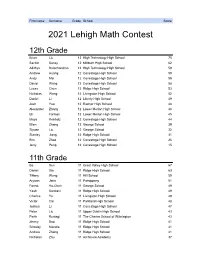

2021 Lehigh Math Contest

First name Surname Grade School Score 2021 Lehigh Math Contest 12th Grade Brian Liu 12 High Technology High School 75 Sachin Sahay 12 Millburn High School 62 Adithya Balachandran 12 High Technology High School 59 Andrew Huang 12 Conestoga High School 59 Andy Mei 12 Conestoga High School 59 David Wang 12 Conestoga High School 58 Lucas Chen 12 Ridge High School 53 Nicholas Wang 12 Livingston High School 52 Daniel Li 12 Liberty High School 49 Josh Yoo 12 Radnor High School 48 Alexander Zhang 12 Lower Merion High School 48 Eli Forman 12 Lower Merion High School 45 Maya Rebholz 12 Conestoga High School 44 Ellen Zhang 12 George School 39 Siyuan Liu 12 George School 32 Stanley Jiang 12 Ridge High School 31 Eric Zhao 12 Conestoga High School 26 Jerry Peng 12 Conestoga High School 15 11th Grade Bo Sun 11 Great Valley High School 67 Daniel Xia 11 Ridge High School 63 Tiffany Wang 11 Hill School 59 Aryaan Jena 11 Parsippany 51 Forest Ho-Chen 11 George School 49 Yash Samtani 11 Ridge High School 49 Charles Yu 11 Livingston High School 49 Victor Cai 11 Parkland High School 48 Joshua Li 11 Conestoga High School 47 Peter Liu 11 Upper Dublin High School 43 Parth Rustagi 11 The Charter School of Wilmington 43 Jimmy Bao 11 Ridge High School 41 Sribalaji Marella 11 Ridge High School 41 Andrew Zhang 11 Ridge High School 41 Nicholas Zhu 11 Archmere Academy 37 First name Surname Grade School Score Heran Yang 11 The Charter School of Wilmington 36 Divyesh Murugan 11 Academy of Math, Science and Engineering 35 Jeffrey Tan 11 Conestoga High School 34 Ben Zhao -

CONESTOGA HIGH SCHOOL Tredyffrin/Easttown School District

PROFILE 2017 - 2018 CONESTOGA HIGH SCHOOL Tredyffrin/Easttown School District 200 Irish Road • Berwyn, PA 19312-1260 • www.tesd.net/stoga Phone: (610) 240-1000 • Fax: (610) 240-1061 • CBC 390295 Administration Counselors Dr Richard Gusick Superintendent Mrs Laureen Stohrer(A-Br) StohrerL@tesd net 610-240-1008 Dr Amy Meisinger .......................................................................................Principal Mrs Rachelle Gough (Bu-Dh) GoughR@tesd net 610-240-1011 Mr James Bankert Assistant Principal Ms Katherine Barthelmeh(Di-Gai) BarthelmehK@tesd net 610-240-1007 Mr Brian Samson (Gal-Ja) SamsonB@tesd net 610-240-1012 Dr Patrick Boyle Assistant Principal Ms Melissa Boltz (Je-L) BoltzM@tesd net 610-240-1051 Mr Anthony DiLella Assistant Principal Mrs Jennifer Kratsa (M-Na) KratsaJ@tesd net 610-240-1010 Ms Misty Whelan Assistant Principal Mr Daniel McDermott (Ne-R) McDermottD@tesd net 610-240-1009 Mr Kevin Pechin Athletic Director Mrs Leashia Lewis (S-Te) LewisLe@tesd net 610-240-1038 Mrs Megan Smyth (Th-Z) SmythM@tesd net 610-240-1013 General Information National Merit Recognition 2017 Grades 9 - 12 Type of School Public • 34 National Merit Scholarship Semifinalists Enrollment 2,209 Length of Semester 20 Weeks • 26 National Merit Commended Students Class Periods 43 minutes Periods per Day 8 Periods • 2 National Hispanic Scholars Teaching Faculty 139 Teacher to Student Ratio 1:16 College Board Advanced Placement Community Located 15 miles west of Philadelphia in eastern Chester County, Tredyffrin In May 2017, 863 Conestoga students -

Conestoga High School

2012 Conestoga High School 200 Irish Road • Berwyn, PA 19312-1260 2013 Phone (610) 240-1000 • FAX (610) 240-1055 Home page • http://www.tesd.net/stoga College Board Code 390295 P R O F I RECOGNIZED SCHOOL OF EXCELLENCE L United States Department of Education E Tredyffrin/Easttown School District "To inspire a passion for learning, personal integrity, the pursuit of excellence, and social responsibility in each student" - T/E Strategic Plan Conestoga High School Tredyffrin/Easttown School District 2012-2013 Administration Student Services Staff Dr. Daniel Waters, Superintendent of Schools Grades 9 through 12 Dr. Amy Meisinger, Principal Mrs. Laureen McGloin (A-Br) Mrs. Jennifer Kratsa (M-Na) Mr. Patrick Boyle, Assistant Principal Mrs. Rachelle Gough (Bu-Dh) Mr. Andrew Mullen (Ne-R) Mr. Kevin Fagan, Assistant Principal Mrs. Misty Whelan (Di-Gai) Ms. Leashia Rahr (S-Te) Mr. Andrew Phillips, Assistant Principal Mr. Brian Samson (Gal-Ja) Ms. Megan Ryan (Th-Z) Mrs. Michele Staves, Assistant Principal Ms. Melissa Boltz (Je-L) Mrs. Cathy Lucas, Secretary, 610-240-1006; Ms. Beverly Cunningham, Director of Athletics, Mr. Patrick Boyle Secretary, 610-240-1017; Mrs. Gretchen Barkman, Registrar, 610-240-1016 Community and High School Located 15 miles west of Philadelphia in eastern Chester County, Tredyffrin and Easttown Townships form a suburban school district whose residents strongly support education and primarily engage in professional and business occupations. Conestoga High School is a four-year public school that emphasizes college preparation. The current enrollment is approxi- mately 2,060 students. Conestoga is consistently among the top high schools in the state in academic excellence.