The Evaluation of Dizzinessin Elderly Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Post-Tympanoplasty Evaluation of the Factors Affecting Development of Myringosclerosis in the Graft: a Clinical Study

Int Adv Otol 2014; 10(2): 102-6 • DOI: 10.5152/iao.2014.40 Original Article A Post-Tympanoplasty Evaluation of the Factors Affecting Development of Myringosclerosis in the Graft: A Clinical Study Can Özbay, Rıza Dündar, Erkan Kulduk, Kemal Fatih Soy, Mehmet Aslan, Hüseyin Katılmış Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Şifa University Faculty of Medicine, İzmir, Turkey (CÖ) Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Mardin State Hospital, Mardin, Turkey (RD, EK, KFS, MA) Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Katip Çelebi University Atatürk Training and Research Hospital, İzmir, Turkey (HK) OBJECTIVE: Myringosclerosis (MS) is a pathological condition characterized by hyaline degeneration and calcification of the collagenous structure of the fibrotic layer of the tympanic membrane, which may develop after trauma, infection, or inflammation as myringotomy, insertion of a ventila- tion tube, or myringoplasty. The aim of our study was to both reveal and evaluate the impact of the factors that might be effective on the post-tym- panoplasty development of myringosclerosis in the graft. MATERIALS and METHODS: In line with this objective, a total of 108 patients (44 males and 64 females) aged between 11 and 66 years (mean age, 29.5 years) who had undergone type 1 tympanoplasty (TP) with an intact canal wall technique and type 2 TP, followed up for an average of 38.8 months, were evaluated. In the presence of myringosclerosis, in consideration of the tympanic membrane (TM) quadrants involved, the influential factors were analyzed in our study, together with the development of myringosclerosis, including preoperative factors, such as the presence of myringosclerosis in the residual and also contralateral tympanic membrane, extent and location of the perforation, and perioperative factors, such as tympanosclerosis in the middle ear and mastoid cavity, cholesteatoma, granulation tissue, and type of the operation performed. -

Changes in the Three-Dimensional Angular Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Following Intratympanic Gentamicin for Menieres Disease

JARO 03: 430±443 82002) DOI: 10.1007/s101620010053 JARO Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology Changes in the Three-Dimensional Angular Vestibulo-Ocular Re¯ex following Intratympanic Gentamicin for MeÂnieÁre's Disease 1 1±3 4,5 1 JOHN P. CAREY, LLOYD B. MINOR, GRACE C.Y. PENG, CHARLES C. DELLA SANTINA, 6 7 PHILLIP D. CREMER, AND THOMAS HASLWANTER 1 1Department of Otolaryngology±Head and Neck Surgery, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA 2Department of Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA 3Department of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA 4Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA 1 5Department of Biomedical Engineering, Catholic University of America, Washington, DC 20064, USA 6Eye and Ear Research Unit, Institute of Clinical Neurosciences, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia 7Department of Neurology, ZuÈrich University Hospital, ZuÈrich, Switzerland Received: 19 June 2000; Accepted: 21 January 2002; Online publication: 26 March 2002 ABSTRACT these gain values and those for head thrusts that ex- cited the contralateral canals were <2%. In contrast, The 3-dimensional angular vestibulo-ocular re¯exes caloric asymmetries averaged 40% 32%. Intra- 8AVOR) elicited by rapid rotary head thrusts were tympanic gentamicin resulted in decreased gains studied in 17 subjects with unilateral MeÂnieÁre's attributable to each canal on the treated side: disease before and 2±10 weeks after treatment with 0.40 0.12 8HC), 0.35 0.14 8AC), 0.31 0.14 8PC) intratympanic gentamicin and in 13 subjects after 8p < 0.01). However, the gains attributable to con- surgical unilateral vestibular destruction 8SUVD). -

Hearing Loss Due to Myringotomy and Tube Placement and the Role of Preoperative Audiograms

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Hearing Loss Due to Myringotomy and Tube Placement and the Role of Preoperative Audiograms Mark Emery, MD; Peter C. Weber, MD Background: Postoperative complications of myrin- erative and postoperative sensorineural and conductive gotomy and tube placement often include otorrhea, tym- hearing loss. panosclerosis, and tympanic membrane perforation. How- ever, the incidence of sensorineural or conductive hearing Results: No patient developed a postoperative sensori- loss has not been documented. Recent efforts to curb the neural or conductive hearing loss. All patients resolved use of preoperative audiometric testing requires docu- their conductive hearing loss after myringotomy and tube mentation of this incidence. placement. There was a 1.3% incidence of preexisting sen- sorineural hearing loss. Objective: To define the incidence of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss associated with myrin- Conclusions: The incidence of sensorineural or con- gotomy and tube placement. ductive hearing loss after myringotomy and tube place- ment is negligible and the use of preoperative audiomet- Materials and Methods: A retrospective chart re- ric evaluation may be unnecessary in selected patients, view of 550 patients undergoing myringotomy and tube but further studies need to be done to corroborate this placement was performed. A total of 520 patients under- small data set. going 602 procedures (1204 ears), including myrin- gotomy and tube placement, were assessed for preop- Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:421-424 TITIS MEDIA (OM) is one erative hearing status and whether it has of the most frequent dis- either improved or remained stable after eases of childhood, af- MTT. A recent report by Manning et al11 fecting at least 80% of demonstrated a 1% incidence of preop- children prior to school erative sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) Oentry.1-4 Because of the high incidence of in children undergoing MTT. -

Myringotomy and Ear Tubes WHAT IS THE

Myringotomy and Ear Tubes Myringotomy and Ear Tubes What to expect after surgery when ear tubes are placed: WHAT IS THE OPERATION? 1. DIET: There may be nausea or vomiting for a few hours after the operation. Start by drinking liquids and advance to a A very small slit is made in the eardrum for the purpose of draining regular diet as tolerated. fluid out from behind the eardrum and allowing air to get in behind the eardrum. After the slit is made a very tiny plastic or silicone rubber 2. PAIN: Generally, there is little pain, but Tylenol or Tempra may tube is inserted in the eardrum to keep the small hole open. be taken if needed every six hours. If pain medication is needed beyond 2 days, contact the doctor. WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THE VENTILATION TUBE? 3. EAR DRAINAGE AFTER THE PROCEDURE: A little bloody Fluid in the ear causes hearing loss, promotes infection, and causes discharge for a few days is expected. Occasionally, there will discomfort. The function of the ventilation tube is to allow air to flow be a lot of mucus drainage from one or both of the ears, for between the outer ear and the middle ear, which equalizes air pressure perhaps a week. It is not unusual if there is no drainage. in the ear. It takes over the function of the patient’s own eustachian tube, which is not functioning properly. The tube will also allow 4. EAR DRAINAGE AFTER THE FIRST WEEK OR TWO: Usually there infection, if it recurs, to drain out of the ear. -

Tympanostomy Tubes in Children Final Evidence Report: Appendices

Health Technology Assessment Tympanostomy Tubes in Children Final Evidence Report: Appendices October 16, 2015 Health Technology Assessment Program (HTA) Washington State Health Care Authority PO Box 42712 Olympia, WA 98504-2712 (360) 725-5126 www.hca.wa.gov/hta/ [email protected] Tympanostomy Tubes Provided by: Spectrum Research, Inc. Final Report APPENDICES October 16, 2015 WA – Health Technology Assessment October 16, 2015 Table of Contents Appendices Appendix A. Algorithm for Article Selection ................................................................................................. 1 Appendix B. Search Strategies ...................................................................................................................... 2 Appendix C. Excluded Articles ....................................................................................................................... 4 Appendix D. Class of Evidence, Strength of Evidence, and QHES Determination ........................................ 9 Appendix E. Study quality: CoE and QHES evaluation ................................................................................ 13 Appendix F. Study characteristics ............................................................................................................... 20 Appendix G. Results Tables for Key Question 1 (Efficacy and Effectiveness) ............................................. 39 Appendix H. Results Tables for Key Question 2 (Safety) ............................................................................ -

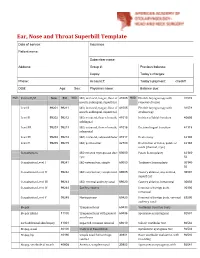

Ear, Nose and Throat Superbill Template Date of Service: Insurance: Patient Name

Ear, Nose and Throat Superbill Template Date of service: Insurance: Patient name: Subscriber name: Address: Group #: Previous balance: Copay: Today’s charges: Phone: Account #: Today’s payment: check# DOB: Age: Sex: Physician name: Balance due: MOD. Patient E/M New Est MOD. I&D, intraoral, tongue, floor of 41005 MOD. Flexible laryngoscopy with 31578 mouth, sublingual, superficial removal of lesion Level I 99201 99211 I&D, intraoral, tongue, floor of 41005 Flexible laryngoscopy with 31579 mouth, sublingual, superficial stroboscopy Level II 99202 99212 I&D, extraoral, floor of mouth, 41015 Incision of labial frenulum 40806 sublingual Level III 99203 99213 I&D, extraoral, floor of mouth, 41016 Excision lingual frenulum 41115 submental Level IV 99204 99214 I&D, extraoral, submandibular 41017 Uvulectomy 42140 Level V 99205 99215 I&D, peritonsillar 42700 Destruction of lesion, palate or 42160 uvula (thermal, cryo) Consultations I&D infected thyroglossal duct 60000 Palate Somnoplasty 42145- cyst 52 Consultation Level I 99241 I&D external ear, simple 69000 Turbinate Somnoplasty 30140- 52 Consultation Level II 99242 I&D external ear, complicated 69005 Cautery ablation, any method, 30801 superficial Consultation Level III 99243 I&D, external auditory canal 69020 Cautery ablation, intramural 30802 Consultation Level IV 99244 Ear Procedures Removal of foreign body, 30300 intranasal Consultation Level V 99245 Myringotomy 69420 Removal of foreign body, external 69200 auditory canal Biopsy Tympanostomy 69433 Vestibular Function Tests Biopsy (Skin) 11100 -

Myringotomy Surgery with PE Tube Placement Perioperative Instructions

Myringotomy Surgery with PE Tube Placement Perioperative Instructions Introduction What is the purpose of myringotomy surgery? This form is intended to inform you about myringotomy (meer-ing- Treats ear infections that have not responded well to other GOT-o-mee) surgery. During myringotomy surgery, a tube is placed treatments in the eardrum. Topics covered include basic function of the ear, what Improves hearing loss caused by fluid build up occurs during surgery and postop care. Improves speech development delayed by hearing loss How does the ear work? Treats recurrent Eustachian tube dysfunction Treats ear problems associated with cleft palate The outer ear collects sound. The paper-thin eardrum separates the outer ear from the middle ear, a tiny air-filled cavity. The middle ear Benefits of myringotomy surgery may include: contains the bones of hearing, which are attached to the eardrum. Fewer and less severe ear infections When sound waves strike the eardrum, it vibrates and sets the bones Hearing improvement in motion, enabling sound to be transmitted to the inner ear. The inner Improvement of speech ear converts vibrations to electrical signals and sends these signals to the brain. What are the risks of surgery? A healthy middle ear contains air, which enters through the narrow Difficulties related to anesthesia Eustachian tube that connects the back of the nose to the ear. A Failure for the incision to heal after the tube falls out normally functioning Eustachian tube opens to equalize pressure in (tympanic membrane perforation) the middle ear, allowing fluid to exist. Fluid build-up in the middle Scarring of the eardrum ear can block transmission of sound, causing hearing loss and/or Hearing loss setting the stage for recurrent ear infections (otitis media). -

Petubes Patient Handout.Pdf

Division of Pediatric Otolaryngology Information on Tympanostomy Tubes Tympanostomy tubes are small plastic or metal tubes that are placed into the tympanic membrane or ear drum. How long will the tube stay in place? Tubes usually fall out of the ear in 6 months- 2 years. If they remain in longer than 2 to 3 years they are sometimes removed. What is involved with Tympanostomy tube placement? This surgery is usually done under general anesthesia. The eardrum is examined using a microscope. A small hole is made in the ear drum called a myringotomy, fluid is removed, and the tube is placed. Tube in the eardrum What medical conditions are treated with tubes? Recurrent middle ear infections or frequent acute otitis media Otitis media with effusion or fluid in middle ear associated with hearing loss Eustachian tube dysfunction causing hearing loss or eardrum structure changes What is the Eustachian tube? This is the canal that links the middle ear with the throat. This tube allows air into the middle ear and drainage of fluid. This tube grows in width and length until children are about 5 years old. Reasons that the Eustachian tube may not work properly: Viral illness, exposure to allergens or tobacco smoke may lead to swelling of the eustachian tube resulting in fluid buildup in the middle ear. Children with cleft palate and craniofacial syndromes like Down’s syndrome may have poor eustachian tube function. How will Tympanostomy tube help my child? They allow air to re-enter middle ear space They reduce the number and severity of infections They improve hearing loss cause by middle ear fluid Why is adenoidectomy sometimes done with the Tympanostomy tubes? Adenoidectomy is the removal of the adenoid tissue behind the nose. -

Evaluation of the Results and Complications of the Ventilation Tubes’ Setting Surgery in Patients with Serous Otitis Media

Artigo Original Evaluation of the Results and Complications of the Ventilation Tubes’ Setting Surgery in Patients with Serous Otitis Media Avaliação de Resultados e Complicações da Cirurgia de Colocação de Tubos de Ventilação em Pacientes com Otite Media Serosa José Ricardo Testa*, Spyros Cardoso Dimatos**, Bárbara Greggio***, Juliana Antoniolli Duarte***. * Doctor of Medicine. Medical Faculty Otorhinolaryngology. ** Master Pediatric Otolaryngology. Medical Graduate Student. *** Medical Residency. Resident. Instituition: UNIFESP / EPM - Federal University of São Paulo Paulista School of Medicine - Department of Pediatric Otolaryngology. São Paulo / SP - Brazil. Mail Address: Juliana Antoniolli Duarte - Rua Pedro de Toledo, 947 - 2º andar - Vila Clementino - São Paulo / SP - Brazil - ZIP CODE: 04039-002 - Telefax: (+55 11) 5539-5378 - E-mail: [email protected] Article received in em March 1, 2010. Article approved in March 13, 2010. SUMMARY Introduction: Tympanostomy for ventilation tube setting is one of the surgeries more frequent performed in patients in the pediatric age group. Objective: This study evaluates the indications and complications post operatives more frequents in this otorhinolaryngological practice in a school hospital. Method: It was realized a series type retrospective study of cases in which 109 pediatric patients, that have received ventilation tube were evaluated as for the post operative indication and attendance for the otorhinolaryngology sector of the Paulista Medicine School for 2007 to 2008. Results: The age’ average found was 7,37 years, being the majority of the patients of the male sex (59,63%). All the cases have had as surgical indication serous otitis media. The taxes of complications found were lower than those related for the literature with 3,43% of residual perforation with necessity of surgical re intervention and 5,47% do not presented a audiometric improvement needing a new insertion of ventilation tube. -

Myringotomy Post-Operative Instructions

Myringotomy and tube placement Arizona Sinus Center Phone (602) 258-9859 Fax (602) 256-0820 Post-operative Instructions Following Myringotomy and tube placement General: Myringotomy means a surgically-created hole in the ear drum. After a myringotomy is performed a tube is often placed in the hole to keep it open. This procedure is designed to allow equalization of pressure between the middle ear space and the outside environment. Myringotomy and tube placement are necessary when the Eustachian tube (natural ventilation duct between the throat and middle ear) does not function properly. Generally, the pressure equalizing tube placed at the time of surgery remains in the ear drum anywhere between 4-18 months. Variable ear drum healing and different types of tubes can make this duration shorter or longer. The procedure is usually performed under local anesthesia (numbing medication only) in adults and general anesthesia (completely asleep) in children. Diet: There are no dietary restrictions following myringotomy and tube placement. Pain control: You may experience mild ear pain following myringotomy and tube placement. This is usually well controlled with acetaminophen. Occasionally mild narcotic pain relievers may be prescribed by your surgeon. Continued on opposite side Ear Care Following Surgery: Please use the medicated ear drops as prescribed by your surgeon. Avoid submerging your head under water as this could allow water to enter the middle ear space through the tubes and temporary pain, vertigo or infection may result. Small amounts of clean water (shower or well-maintained pool) may enter the ear canal and usually do not cause problems while the tubes are in place. -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

Meniere's Disease

4/4/2019 MENIERE’S DISEASE & OTHER OTOLOGIC CONDITIONS Michael S. Harris, MD Assistant Professor Division of Otology and Neuro-otologic Skull Base Surgery Department of Otolaryngology & Communication Sciences Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI A Practical Guide to Dizziness and Disequilibrium April 5, 2019 DISCLOSURES • Consultant for Advanced Bionics • Research support provided by American Neurotology Society and the Triological Society A Practical Guide to Dizziness and Disequilibrium April 5, 2019 OVERVIEW • Classic picture Meniere’s Disease • Diagnosis Vestibular Neuritis • Treatment Labyrinthitis Approach Vestibular Schwannoma (Acoustic Neuroma) A Practical Guide to Dizziness and Disequilibrium April 5, 2019 1 4/4/2019 IMPORTANT THEMES • Largely clinical diagnosis. Careful clinic history is key. • Consistency/agreement in language essential. “Dizzy” vs Vertigo: “sensation of self motion when no self motion is occurring” • Temporal characteristics matter and the condition evolves. • Often cannot be made on first presentation alone. A Practical Guide to Dizziness and Disequilibrium April 5, 2019 MENIERE’S DISEASE • Incidence 3.5 to 500 per 100,000 • Female to male ratio 1.3:1 • Peak incidence ages 40 to 60 years A Practical Guide to Dizziness and Disequilibrium April 5, 2019 Vertigo MENIERE’S Hearing TRIAD Loss Tinnitus A Practical Guide to Dizziness and Disequilibrium April 5, 2019 2 4/4/2019 CLASSIC PICTURE… • Recurrent random, spontaneous vertigo - Nausea/emesis…debilitating - Not provoked - No positional/body movement