Review of Anesthesia for Middle Ear Surgery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CASE REPORT Resolution of Delayed Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss After Stapedectomy

The Mediterranean Journal of Otology CASE REPORT Resolution of Delayed Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss After Stapedectomy: A Case Report and Review of the Literature Noam Yehudai, MD, Michal Luntz, MD From the Department of Significant sensorineural hearing loss may develop immediately after suc- Otolaryngology, Head and Neck cessful stapedectomy but sometimes occurs months or even years later. Surgery, Bnai-Zion Medical The rate of recovery from that disorder has not been determined. Several Center, Technion-Israel School of Technology, Haifa, Israel reports in the 1960s described patients with delayed sensorineural hear- ing loss, but that entity has not been mentioned in the English-language Correspondence literature for the last 30 years. We present a review of the literature on this Michal Luntz, MD postsurgical auditory complication and describe a patient with delayed Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery poststapedectomy sensorineural hearing loss that developed 15 months Bnai-Zion Medical Center, after surgery and resolved completely after treatment with an oral steroid. Technion-Israel School of Technology 47 Golomb St, PO Box 4940, Haifa 31048, Israel Phone: 972-4-8359544 Fax: 972-4-8361069 E-mail: [email protected] Submitted: 05 February, 2006 Revised: 07 May, 2006 Accepted: 09 May, 2006 Mediterr J Otol 2006; 3: 156-160 Copyright 2005 © The Mediterranean Society of Otology and Audiology 156 Resolution of Delayed Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss After Stapedectomy: A Case Report and Review of the Literature -

A Post-Tympanoplasty Evaluation of the Factors Affecting Development of Myringosclerosis in the Graft: a Clinical Study

Int Adv Otol 2014; 10(2): 102-6 • DOI: 10.5152/iao.2014.40 Original Article A Post-Tympanoplasty Evaluation of the Factors Affecting Development of Myringosclerosis in the Graft: A Clinical Study Can Özbay, Rıza Dündar, Erkan Kulduk, Kemal Fatih Soy, Mehmet Aslan, Hüseyin Katılmış Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Şifa University Faculty of Medicine, İzmir, Turkey (CÖ) Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Mardin State Hospital, Mardin, Turkey (RD, EK, KFS, MA) Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Katip Çelebi University Atatürk Training and Research Hospital, İzmir, Turkey (HK) OBJECTIVE: Myringosclerosis (MS) is a pathological condition characterized by hyaline degeneration and calcification of the collagenous structure of the fibrotic layer of the tympanic membrane, which may develop after trauma, infection, or inflammation as myringotomy, insertion of a ventila- tion tube, or myringoplasty. The aim of our study was to both reveal and evaluate the impact of the factors that might be effective on the post-tym- panoplasty development of myringosclerosis in the graft. MATERIALS and METHODS: In line with this objective, a total of 108 patients (44 males and 64 females) aged between 11 and 66 years (mean age, 29.5 years) who had undergone type 1 tympanoplasty (TP) with an intact canal wall technique and type 2 TP, followed up for an average of 38.8 months, were evaluated. In the presence of myringosclerosis, in consideration of the tympanic membrane (TM) quadrants involved, the influential factors were analyzed in our study, together with the development of myringosclerosis, including preoperative factors, such as the presence of myringosclerosis in the residual and also contralateral tympanic membrane, extent and location of the perforation, and perioperative factors, such as tympanosclerosis in the middle ear and mastoid cavity, cholesteatoma, granulation tissue, and type of the operation performed. -

Changes in the Three-Dimensional Angular Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Following Intratympanic Gentamicin for Menieres Disease

JARO 03: 430±443 82002) DOI: 10.1007/s101620010053 JARO Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology Changes in the Three-Dimensional Angular Vestibulo-Ocular Re¯ex following Intratympanic Gentamicin for MeÂnieÁre's Disease 1 1±3 4,5 1 JOHN P. CAREY, LLOYD B. MINOR, GRACE C.Y. PENG, CHARLES C. DELLA SANTINA, 6 7 PHILLIP D. CREMER, AND THOMAS HASLWANTER 1 1Department of Otolaryngology±Head and Neck Surgery, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA 2Department of Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA 3Department of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA 4Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA 1 5Department of Biomedical Engineering, Catholic University of America, Washington, DC 20064, USA 6Eye and Ear Research Unit, Institute of Clinical Neurosciences, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia 7Department of Neurology, ZuÈrich University Hospital, ZuÈrich, Switzerland Received: 19 June 2000; Accepted: 21 January 2002; Online publication: 26 March 2002 ABSTRACT these gain values and those for head thrusts that ex- cited the contralateral canals were <2%. In contrast, The 3-dimensional angular vestibulo-ocular re¯exes caloric asymmetries averaged 40% 32%. Intra- 8AVOR) elicited by rapid rotary head thrusts were tympanic gentamicin resulted in decreased gains studied in 17 subjects with unilateral MeÂnieÁre's attributable to each canal on the treated side: disease before and 2±10 weeks after treatment with 0.40 0.12 8HC), 0.35 0.14 8AC), 0.31 0.14 8PC) intratympanic gentamicin and in 13 subjects after 8p < 0.01). However, the gains attributable to con- surgical unilateral vestibular destruction 8SUVD). -

Hearing Loss Due to Myringotomy and Tube Placement and the Role of Preoperative Audiograms

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Hearing Loss Due to Myringotomy and Tube Placement and the Role of Preoperative Audiograms Mark Emery, MD; Peter C. Weber, MD Background: Postoperative complications of myrin- erative and postoperative sensorineural and conductive gotomy and tube placement often include otorrhea, tym- hearing loss. panosclerosis, and tympanic membrane perforation. How- ever, the incidence of sensorineural or conductive hearing Results: No patient developed a postoperative sensori- loss has not been documented. Recent efforts to curb the neural or conductive hearing loss. All patients resolved use of preoperative audiometric testing requires docu- their conductive hearing loss after myringotomy and tube mentation of this incidence. placement. There was a 1.3% incidence of preexisting sen- sorineural hearing loss. Objective: To define the incidence of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss associated with myrin- Conclusions: The incidence of sensorineural or con- gotomy and tube placement. ductive hearing loss after myringotomy and tube place- ment is negligible and the use of preoperative audiomet- Materials and Methods: A retrospective chart re- ric evaluation may be unnecessary in selected patients, view of 550 patients undergoing myringotomy and tube but further studies need to be done to corroborate this placement was performed. A total of 520 patients under- small data set. going 602 procedures (1204 ears), including myrin- gotomy and tube placement, were assessed for preop- Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:421-424 TITIS MEDIA (OM) is one erative hearing status and whether it has of the most frequent dis- either improved or remained stable after eases of childhood, af- MTT. A recent report by Manning et al11 fecting at least 80% of demonstrated a 1% incidence of preop- children prior to school erative sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) Oentry.1-4 Because of the high incidence of in children undergoing MTT. -

Myringotomy and Ear Tubes WHAT IS THE

Myringotomy and Ear Tubes Myringotomy and Ear Tubes What to expect after surgery when ear tubes are placed: WHAT IS THE OPERATION? 1. DIET: There may be nausea or vomiting for a few hours after the operation. Start by drinking liquids and advance to a A very small slit is made in the eardrum for the purpose of draining regular diet as tolerated. fluid out from behind the eardrum and allowing air to get in behind the eardrum. After the slit is made a very tiny plastic or silicone rubber 2. PAIN: Generally, there is little pain, but Tylenol or Tempra may tube is inserted in the eardrum to keep the small hole open. be taken if needed every six hours. If pain medication is needed beyond 2 days, contact the doctor. WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THE VENTILATION TUBE? 3. EAR DRAINAGE AFTER THE PROCEDURE: A little bloody Fluid in the ear causes hearing loss, promotes infection, and causes discharge for a few days is expected. Occasionally, there will discomfort. The function of the ventilation tube is to allow air to flow be a lot of mucus drainage from one or both of the ears, for between the outer ear and the middle ear, which equalizes air pressure perhaps a week. It is not unusual if there is no drainage. in the ear. It takes over the function of the patient’s own eustachian tube, which is not functioning properly. The tube will also allow 4. EAR DRAINAGE AFTER THE FIRST WEEK OR TWO: Usually there infection, if it recurs, to drain out of the ear. -

The Evaluation of Dizzinessin Elderly Patients

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.68.801.558 on 1 July 1992. Downloaded from Postgrad Med J (1992) 68, 558 561 The Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine, 1992 The evaluation ofdizziness in elderly patients N. Ahmad, J.A. Wilson', R.M. Barr-Hamilton2, D.M. Kean3 and W.J. MacLennan Geriatric Medicine Unit, City Hospital, Edinburgh and Departments of'Otolaryngology, 2Audiology and 3Radiology, Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, UK Summary: Twenty-one elderly patients with dizziness underwent a comprehensive medical and otoneurological evaluation. The majority had vertigo, limited mobility and restricted neck movements. Poor visual acuity, postural hypotension and presbyacusis were also frequent findings. Electronystagmo- graphy revealed positional nystagmus in 12, disordered smooth pursuit in 18, and abnormal caloric responses in nine. Magnetic resonance imaging showed ischaemic changes in six out of eight patients. Although dizziness in the elderly is clearly multifactorial, the suggested importance of vertebrobasilar ischaemia warrants further consideration as vertigo has been shown to be a risk factor for stroke. Introduction More than one third of individuals over the age of Patients and methods 65 years experience recurrent attacks of dizziness.' Serious consequences include a high incidence of The subjects were 21 patients who had been falls in patients with non-rotating dizziness, and an referred to either the care ofthe elderly unit or ENTcopyright. increased risk of stroke in those with vertigo (a Department in Edinburgh for the investigation of sensation ofmovement relative to surroundings)." 2 dizziness. There were five males and 16 females The causes ofdizziness are legion.3 Its diagnosis, aged 68-95 years (median = 81 years). -

Consultation Diagnoses and Procedures Billed Among Recent Graduates Practicing General Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surger

Eskander et al. Journal of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery (2018) 47:47 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-018-0293-8 ORIGINALRESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Consultation diagnoses and procedures billed among recent graduates practicing general otolaryngology – head & neck surgery in Ontario, Canada Antoine Eskander1,2,3* , Paolo Campisi4, Ian J. Witterick5 and David D. Pothier6 Abstract Background: An analysis of the scope of practice of recent Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery (OHNS) graduates working as general otolaryngologists has not been previously performed. As Canadian OHNS residency programs implement competency-based training strategies, this data may be used to align residency curricula with the clinical and surgical practice of recent graduates. Methods: Ontario billing data were used to identify the most common diagnostic and procedure codes used by general otolaryngologists issued a billing number between 2006 and 2012. The codes were categorized by OHNS subspecialty. Practitioners with a narrow range of procedure codes or a high rate of complex procedure codes, were deemed subspecialists and therefore excluded. Results: There were 108 recent graduates in a general practice identified. The most common diagnostic codes assigned to consultation billings were categorized as ‘otology’ (42%), ‘general otolaryngology’ (35%), ‘rhinology’ (17%) and ‘head and neck’ (4%). The most common procedure codes were categorized as ‘general otolaryngology’ (45%), ‘otology’ (23%), ‘head and neck’ (13%) and ‘rhinology’ (9%). The top 5 procedures were nasolaryngoscopy, ear microdebridement, myringotomy with insertion of ventilation tube, tonsillectomy, and turbinate reduction. Although otology encompassed a large proportion of procedures billed, tympanoplasty and mastoidectomy were surprisingly uncommon. Conclusion: This is the first study to analyze the nature of the clinical and surgical cases managed by recent OHNS graduates. -

Tympanostomy Tubes in Children Final Evidence Report: Appendices

Health Technology Assessment Tympanostomy Tubes in Children Final Evidence Report: Appendices October 16, 2015 Health Technology Assessment Program (HTA) Washington State Health Care Authority PO Box 42712 Olympia, WA 98504-2712 (360) 725-5126 www.hca.wa.gov/hta/ [email protected] Tympanostomy Tubes Provided by: Spectrum Research, Inc. Final Report APPENDICES October 16, 2015 WA – Health Technology Assessment October 16, 2015 Table of Contents Appendices Appendix A. Algorithm for Article Selection ................................................................................................. 1 Appendix B. Search Strategies ...................................................................................................................... 2 Appendix C. Excluded Articles ....................................................................................................................... 4 Appendix D. Class of Evidence, Strength of Evidence, and QHES Determination ........................................ 9 Appendix E. Study quality: CoE and QHES evaluation ................................................................................ 13 Appendix F. Study characteristics ............................................................................................................... 20 Appendix G. Results Tables for Key Question 1 (Efficacy and Effectiveness) ............................................. 39 Appendix H. Results Tables for Key Question 2 (Safety) ............................................................................ -

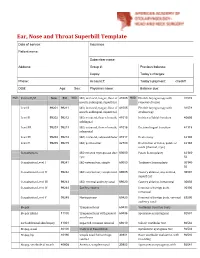

Ear, Nose and Throat Superbill Template Date of Service: Insurance: Patient Name

Ear, Nose and Throat Superbill Template Date of service: Insurance: Patient name: Subscriber name: Address: Group #: Previous balance: Copay: Today’s charges: Phone: Account #: Today’s payment: check# DOB: Age: Sex: Physician name: Balance due: MOD. Patient E/M New Est MOD. I&D, intraoral, tongue, floor of 41005 MOD. Flexible laryngoscopy with 31578 mouth, sublingual, superficial removal of lesion Level I 99201 99211 I&D, intraoral, tongue, floor of 41005 Flexible laryngoscopy with 31579 mouth, sublingual, superficial stroboscopy Level II 99202 99212 I&D, extraoral, floor of mouth, 41015 Incision of labial frenulum 40806 sublingual Level III 99203 99213 I&D, extraoral, floor of mouth, 41016 Excision lingual frenulum 41115 submental Level IV 99204 99214 I&D, extraoral, submandibular 41017 Uvulectomy 42140 Level V 99205 99215 I&D, peritonsillar 42700 Destruction of lesion, palate or 42160 uvula (thermal, cryo) Consultations I&D infected thyroglossal duct 60000 Palate Somnoplasty 42145- cyst 52 Consultation Level I 99241 I&D external ear, simple 69000 Turbinate Somnoplasty 30140- 52 Consultation Level II 99242 I&D external ear, complicated 69005 Cautery ablation, any method, 30801 superficial Consultation Level III 99243 I&D, external auditory canal 69020 Cautery ablation, intramural 30802 Consultation Level IV 99244 Ear Procedures Removal of foreign body, 30300 intranasal Consultation Level V 99245 Myringotomy 69420 Removal of foreign body, external 69200 auditory canal Biopsy Tympanostomy 69433 Vestibular Function Tests Biopsy (Skin) 11100 -

High-Resolution Three-Dimensional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Vestibular Labyrinth in Patients with Atypical and Intractable Benign Positional Vertigo

Original Paper ORL 2001;63:165–177 Received: February 22, 2001 Accepted: February 22, 2001 High-Resolution Three-Dimensional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Vestibular Labyrinth in Patients with Atypical and Intractable Benign Positional Vertigo Bruno Schratzenstaller a Carola Wagner-Manslau b Christoph Alexiou a Wolfgang Arnold a aDepartment of Otolaryngology, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technical University of Munich, and bInstitute of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Klinikum München-Dachau, Dachau, Germany Key Words sections through the ampullary region and the adjoining Benign paroxysmal vertigo W Atypical positional vertigo W utricle showed no abnormalities, there were significant High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging W structural changes in the semicircular canals, which are Three-dimensional reconstruction able to provide an explanation for the symptoms of a heavy cupula. Copyright © 2001 S. Karger AG, Basel Abstract Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a most common cause of dizziness and usually a self-limited dis- Introduction ease, although a small percentage of patients suffer from a permanent form and do not respond to any treatment. Many patients consult their physician because of dizzi- This persistent form of BPPV is thought to have a differ- ness or poor balance. Benign paroxysmal positional ver- ent underlying pathophysiology than the generally ac- tigo (BPPV) is probably the most common cause of ver- cepted canalolithiasis theory. We investigated 5 patients tigo [1] and the most common peripheral vestibular disor- who did not respond to physical treatment, presented der [2, 3]. It is a positional vertigo of sudden onset, trig- with an atypical concomitant nystagmus or both with gered by rapid changes of head and body position and high-resolution three-dimensional magnetic resonance with concomitant nystagmus of short duration. -

MICHAEL T. TEIXIDO, MD Curriculum Vitae 1

MICHAEL T. TEIXIDO, M.D. Curriculum Vitae 1 CURRICULUM VITAE (Revised 1/2017) Michael Thomas Teixido, M.D. Office Address ENT & Allergy of Delaware 1941 Limestone Road, Suite 210 Wilmington, Delaware 19808 Office Phone (302) 998-0300 Fax (302) 998-5111 Websites http://www.entad.org/doctor/dr-michael-teixido-md/ http://www.dbi.udel.edu/biographies/michael-teixido-2 https://www.youtube.com/user/DRMTCI Birth Date December 20, 1959 Birthplace Wilmington, Delaware Foreign Language Spanish Wife’s Name Ilianna Valentinovna Teixido Children Sophia, Misha EDUCATION Degree Dates GRADUATE Bowman Gray School of Medicine Winston-Salem, North Carolina M.D. 8/81 – 6/85 UNDERGRADUATE Wake Forest University Winston-Salem, North Carolina B.A. Biology 8/77 – 6/81 PROFESSIONAL TRAINING Clinical Vestibular Disease (Otology Fellowship rotation) Southern Illinois University medical Center, Horst Konrad, M.D., Preceptor October – December 1991 Temporal Bone Anatomy and Histopathology(Otology Fellowship rotation) University of Chicago Temporal Bone Laboratory Raul Hinojosa, Ph.D., Preceptor July – September 1991 Clinical Fellowship in Otology, Neurotology & Skull Base Surgery MICHAEL T. TEIXIDO, M.D. Curriculum Vitae 2 Northwestern University Medical Center Richard J. Wiet, M.D., Preceptor July 1990 – June 1991 Residency, Department of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery Loyola University Medical Center Maywood, Illinois Gregory Matz, M.D., Director November 1986 – June 1990 Visiting Clinician in Otology, Neurotology & Skull Base Surgery House Ear Institute Los -

OTOLARYNGOLOGY to Request These Clinical Privileges, the Following Threshold Criteria Must Be Met: 1

DELINEATION OF PRIVILEGES PRACTICE AREA: OTOLARYNGOLOGY To request these clinical privileges, the following threshold criteria must be met: 1. Licensed by the State of Iowa as M.D. or D.O., AND 2a. Board Certification by the American Board of Otolaryngology or the American Osteopathic Board of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology with certification in otolaryngology, OR 2b. Successful completion of an ACGME or AOA accredited residency program in otolaryngology WITH board certification in 5 years or less of residency completion. AND 3. Maintain admitting otolaryngology privileges at one of the UnityPoint Health-Des Moines Hospitals, one of the Mercy Health Network-Des Moines Hospitals, VA Central Iowa Health Care System or Broadlawns Medical Center. Surgeons with VA privileges only will be limited to schedule adult patients only at the center. OTOLARYNGOLOGY PRIVILEGES - I am requesting otolaryngology surgery privileges for: Requested Granted □ □ Correct or treat various conditions, illnesses, and disorders of the head and neck affecting the ears, facial skeleton, and respiratory and upper alimentary system □ □ Endoscopy of the larynx, tracheobronchial tree, and esophagus to include biopsy, excision, revision and foreign body removal □ □ Exploration / Debridement / Repair /Excision / Biopsy / Aspiration of soft tissue, skin or nodes of the head or neck □ □ Surgery of the frontal, ethmoid, sphenoid and maxillary sinuses and turbinates, including endoscopic sinus surgery, septoplasty □ □ Surgery of the oral cavity and oral pharynx, hypo pharynx,