Money Market and Debt Instruments Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 06 - Bonds and Other Securities Section 6.2 - Bonds Bond - an Interest Bearing Security That Promises to Pay a Stated Amount of Money at Some Future Date(S)

Chapter 06 - Bonds and Other Securities Section 6.2 - Bonds Bond - an interest bearing security that promises to pay a stated amount of money at some future date(s). maturity date - date of promised final payment term - time between issue (beginning of bond) and maturity date callable bond - may be redeemed early at the discretion of the borrower putable bond - may be redeemed early at the discretion of the lender redemption date - date at which bond is completely paid off - it may be prior to or equal to the maturity date 6-1 Bond Types: Coupon bonds - borrower makes periodic payments (coupons) to lender until redemption at which time an additional redemption payment is also made - no periodic payments, redemption payment includes original loan principal plus all accumulated interest Convertible bonds - at a future date and under certain specified conditions the bond can be converted into common stock Other Securities: Preferred Stock - provides a fixed rate of return for an investment in the company. It provides ownership rather that indebtedness, but with restricted ownership privileges. It usually has no maturity date, but may be callable. The periodic payments are called dividends. Ranks below bonds but above common stock in security. Preferred stock is bought and sold at market price. 6-2 Common Stock - an ownership security without a fixed rate of return on the investment. Common stock dividends are paid only after interest has been paid on all indebtedness and on preferred stock. The dividend rate changes and is set by the Board of Directors. Common stock holders have true ownership and have voting rights for the Board of Directors, etc. -

3. VALUATION of BONDS and STOCK Investors Corporation

3. VALUATION OF BONDS AND STOCK Objectives: After reading this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Understand the role of stocks and bonds in the financial markets. 2. Calculate value of a bond and a share of stock using proper formulas. 3.1 Acquisition of Capital Corporations, big and small, need capital to do their business. The investors provide the capital to a corporation. A company may need a new factory to manufacture its products, or an airline a few more planes to expand into new territory. The firm acquires the money needed to build the factory or to buy the new planes from investors. The investors, of course, want a return on their investment. Therefore, we may visualize the relationship between the corporation and the investors as follows: Capital Investors Corporation Return on investment Fig. 3.1: The relationship between the investors and a corporation. Capital comes in two forms: debt capital and equity capital. To raise debt capital the companies sell bonds to the public, and to raise equity capital the corporation sells the stock of the company. Both stock and bonds are financial instruments and they have a certain intrinsic value. Instead of selling directly to the public, a corporation usually sells its stock and bonds through an intermediary. An investment bank acts as an agent between the corporation and the public. Also known as underwriters, they raise the capital for a firm and charge a fee for their services. The underwriters may sell $100 million worth of bonds to the public, but deliver only $95 million to the issuing corporation. -

Understanding the Z-Spread Moorad Choudhry*

Learning Curve September 2005 Understanding the Z-Spread Moorad Choudhry* © YieldCurve.com 2005 A key measure of relative value of a corporate bond is its swap spread. This is the basis point spread over the interest-rate swap curve, and is a measure of the credit risk of the bond. In its simplest form, the swap spread can be measured as the difference between the yield-to-maturity of the bond and the interest rate given by a straight-line interpolation of the swap curve. In practice traders use the asset-swap spread and the Z- spread as the main measures of relative value. The government bond spread is also considered. We consider the two main spread measures in this paper. Asset-swap spread An asset swap is a package that combines an interest-rate swap with a cash bond, the effect of the combined package being to transform the interest-rate basis of the bond. Typically, a fixed-rate bond will be combined with an interest-rate swap in which the bond holder pays fixed coupon and received floating coupon. The floating-coupon will be a spread over Libor (see Choudhry et al 2001). This spread is the asset-swap spread and is a function of the credit risk of the bond over and above interbank credit risk.1 Asset swaps may be transacted at par or at the bond’s market price, usually par. This means that the asset swap value is made up of the difference between the bond’s market price and par, as well as the difference between the bond coupon and the swap fixed rate. -

Corporate Bonds and Debentures

Corporate Bonds and Debentures FCS Vinita Nair Vinod Kothari Company Kolkata: New Delhi: Mumbai: 1006-1009, Krishna A-467, First Floor, 403-406, Shreyas Chambers 224 AJC Bose Road Defence Colony, 175, D N Road, Fort Kolkata – 700 017 New Delhi-110024 Mumbai Phone: 033 2281 3742/7715 Phone: 011 41315340 Phone: 022 2261 4021/ 6237 0959 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.vinodkothari.com 1 Copyright & Disclaimer . This presentation is only for academic purposes; this is not intended to be a professional advice or opinion. Anyone relying on this does so at one’s own discretion. Please do consult your professional consultant for any matter covered by this presentation. The contents of the presentation are intended solely for the use of the client to whom the same is marked by us. No circulation, publication, or unauthorised use of the presentation in any form is allowed, except with our prior written permission. No part of this presentation is intended to be solicitation of professional assignment. 2 About Us Vinod Kothari and Company, company secretaries, is a firm with over 30 years of vintage Based out of Kolkata, New Delhi & Mumbai We are a team of qualified company secretaries, chartered accountants, lawyers and managers. Our Organization’s Credo: Focus on capabilities; opportunities follow 3 Law & Practice relating to Corporate Bonds & Debentures 4 The book can be ordered by clicking here Outline . Introduction to Debentures . State of Indian Bond Market . Comparison of debentures with other forms of borrowings/securities . Types of Debentures . Modes of Issuance & Regulatory Framework . -

Interest-Rate-Growth Differentials and Government Debt Dynamics

From: OECD Journal: Economic Studies Access the journal at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/19952856 Interest-rate-growth differentials and government debt dynamics David Turner, Francesca Spinelli Please cite this article as: Turner, David and Francesca Spinelli (2012), “Interest-rate-growth differentials and government debt dynamics”, OECD Journal: Economic Studies, Vol. 2012/1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_studies-2012-5k912k0zkhf8 This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. OECD Journal: Economic Studies Volume 2012 © OECD 2013 Interest-rate-growth differentials and government debt dynamics by David Turner and Francesca Spinelli* The differential between the interest rate paid to service government debt and the growth rate of the economy is a key concept in assessing fiscal sustainability. Among OECD economies, this differential was unusually low for much of the last decade compared with the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s. This article investigates the reasons behind this profile using panel estimation on selected OECD economies as means of providing some guidance as to its future development. The results suggest that the fall is partly explained by lower inflation volatility associated with the adoption of monetary policy regimes credibly targeting low inflation, which might be expected to continue. However, the low differential is also partly explained by factors which are likely to be reversed in the future, including very low policy rates, the “global savings glut” and the effect which the European Monetary Union had in reducing long-term interest differentials in the pre-crisis period. -

Sample Debt Validation Letter (Send Via Certified Mail, Return Receipt Requested)

Sample Debt Validation Letter (Send via certified mail, return receipt requested) Date: Your Name Your Address Your City, State, Zip Collection Agency Name Collection Agency Address Collection Agency City, State, Zip RE: Account # (Fill in Account Number) To Whom It May Concern: Be advised this is not a refusal to pay, but a notice that your claim is disputed and validation is requested. Under the Fair Debt collection Practices Act (FDCPA), I have the right to request validation of the debt you say I owe you. I am requesting proof that I am indeed the party you are asking to pay this debt, and there is some contractual obligation that is binding on me to pay this debt. This is NOT a request for “verification” or proof of my mailing address, but a request for VALIDATION made pursuant to 15 USC 1692g Sec. 809 (b) of the FDCPA. I respectfully request that your offices provide me with competent evidence that I have any legal obligation to pay you. At this time I will also inform you that if your offices have or continue to report invalidated information to any of the three major credit bureaus (Equifax, Experian, Trans Union), this action might constitute fraud under both federal and state laws. Due to this fact, if any negative mark is found or continues to report on any of my credit reports by your company or the company you represent, I will not hesitate in bringing legal action against you and your client for the following: Violation of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act and Defamation of Character. -

New Bonds to Make the Eurozone Safer

NEW BONDS TO MAKE THE EUROZONE SAFER Benedikt Fritz, Arne Holzhausen, Lea Pirovino, Tim Schmalle Allianz Research Munich, December 2018 1 NEW BONDS VS STATUS QUO SYNTHETIC EUROBONDS REFORM 01 A DECISION MATRIX 06 2011 EUROBONDS ESBIES PROPOSALS 02 2011 07 2011, 2016, 2017 RED / BLUE BONDS ESIM 03 2010, 2011 08 2011, 2018 PURPLE BONDS APPENDIX 04 2018 09 FURTHER PROPOSALS ACCOUNTABILITY BONDS 05 2015, 2018 2 NEW BONDS VS STATUS QUO: A DECISION MATRIX Red / Blue Accountability Synthetic Eurobonds ESBies ESIM Bonds Bonds Eurobonds Strengthening the Euro Fiscal discipline incentivized 0 0 Euro strengthened as a global currency 0 0 0 Crisis Performance Prevention of excessive rate spikes in crises 0 0 Doom loop broken 0 0 Political Feasibility Political resilience of the mechanism 0 0 Implementation possible 3 EC Green Paper, J.-C. Juncker (then Luxembourg Finance Minister) & G. Tremonti (then Italian Finance Minister), C. Lagarde (IMF Managing Director) EUROBONDS (2011) How does it work? What are the goals? What are the problems? • Bonds are issued jointly by eurozone member • Promotion of further eurozone integration • Entirely incompatible with the no-bailout clause states with joint and several liability • Increased liquidity and lowered borrowing costs, • Higher interest rates for very solvent countries like • Completely replaces national issuance of debt especially in times of financial distress Germany, the Netherlands and Austria • Each member is fully liable for the entire issuance • Resolution of the eurozone debt crisis and • Moral -

Nber Working Papers Series

NBER WORKING PAPERS SERIES WAS THERE A BUBBLE IN THE 1929 STOCK MARKET? Peter Rappoport Eugene N. White Working Paper No. 3612 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 February 1991 We have benefitted from comments made on earlier drafts of this paper by seminar participants at the NEER Summer Institute and Rutgers University. We are particularly indebted to Charles Calomiris, Barry Eicherigreen, Gikas Hardouvelis and Frederic Mishkiri for their suggestions. This paper is part of NBER's research program in Financial Markets and Monetary Economics. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper #3612 February 1991 WAS THERE A BUBBLE IN THE 1929 STOCK MARKET? ABSTRACT Standard tests find that no bubbles are present in the stock price data for the last one hundred years. In contrast., historical accounts, focusing on briefer periods, point to the stock market of 1928-1929 as a classic example of a bubble. While previous studies have restricted their attention to the joint behavior of stock prices and dividends over the course of a century, this paper uses the behavior of the premia demanded on loans collateralized by the purchase of stocks to evaluate the claim that the boom and crash of 1929 represented a bubble. We develop a model that permits us to extract an estimate of the path of the bubble and its probability of bursting in any period and demonstrate that the premium behaves as would be expected in the presence of a bubble in stock prices. -

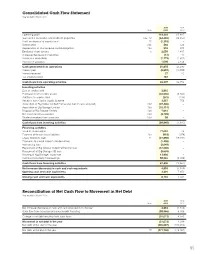

Reconciliation of Net Cash Flow to Movement in Net Debt Year Ended 31 March 2015

Consolidated Cash Flow Statement Year ended 31 March 2015 2015 2014 Note £000 £000 Operating profit 114,203 67,887 Gain on the revaluation of investment properties 13a, 14 (64,465) (28,350) Profit on disposal of surplus land 15 (1,318) – Depreciation 13b 566 526 Depreciation of finance lease capital obligations 13a 918 974 Employee share options 6 2,059 1,437 (Increase)/decrease in inventories (14) 10 Increase in receivables (1,172) (1,652) Increase in payables 1,098 2,458 Cash generated from operations 51,875 43,290 Interest paid (9,692) (10,558) Interest received 27 20 Tax credit received 187 – Cash flows from operating activities 42,397 32,752 Investing activities Sale of surplus land 2,815 – Purchase of non-current assets (42,555) (8,460) Additions to surplus land (231) (136) Receipts from Capital Goods Scheme 3,557 756 Acquisition of Big Yellow Limited Partnership (net of cash acquired) 13d (37,406) – Acquisition of Big Storage Limited 13a (15,114) – Disposal of Big Storage Limited 13a 7,614 – Net investment in associates 13d (3,709) – Dividend received from associate 13d 89 – Cash flows from investing activities (84,940) (7,840) Financing activities Issue of share capital 77,094 42 Payment of finance lease liabilities 13a (918) (974) Equity dividends paid 11 (27,890) (19,591) Payments to cancel interest rate derivatives (1,408) – Refinancing fees (2,649) – Repayment of Big Yellow Limited Partnership loan (57,000) – Repayment of Big Storage AIB loan (9,659) – Drawing of Big Storage Lloyds loan 13,900 – Increase/(reduction) in borrowings -

Corporate Finance Fifth Edition, Global Edition

Corporate Finance Fifth Edition, Global Edition Chapter 6 Valuing Bonds Copyright © 2020 Pearson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Chapter Outline 6.1 Bond Cash Flows, Prices, and Yields 6.2 Dynamic Behavior of Bond Prices 6.3 The Yield Curve and Bond Arbitrage 6.4 Corporate Bonds 6.5 Sovereign Bonds Copyright © 2020 Pearson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 2 Learning Objectives (1 of 4) • Identify the cash flows for both coupon bonds and zero- coupon bonds, and calculate the value for each type of bond. • Calculate the yield to maturity for both coupon and zero- coupon bonds, and interpret its meaning for each. Copyright © 2020 Pearson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 3 Learning Objectives (2 of 4) • Given coupon rate and yield to maturity, determine whether a coupon bond will sell at a premium or a discount; describe the time path the bond’s price will follow as it approaches maturity, assuming prevailing interest rates remain the same over the life of the bond. Copyright © 2020 Pearson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 4 Learning Objectives (3 of 4) • Illustrate the change in bond price that will occur as a result of changes in interest rates; differentiate between the effect of such a change on long-term versus short-term bonds. • Discuss the effect of coupon rate to the sensitivity of a bond price to changes in interest rates. • Define duration, and discuss its use by finance practitioners. Copyright © 2020 Pearson Education Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 5 Learning Objectives (4 of 4) • Calculate the price of a coupon bond using the Law of One Price and a series of zero-coupon bonds. -

Corporate Bonds

investor’s guide CORPORATE BONDS i CONTENTS What are Corporate Bonds? 1 Basic Bond Terms 2 Types of Corporate Bonds 5 Bond Market Characteristics 7 Understanding the Risks 8 Understanding Collateralization and Defaults 13 How Corporate Bonds are Taxed 15 Credit Analysis and Other Important Considerations 17 Glossary 21 All information and opinions contained in this publication were produced by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) from our membership and other sources believed by SIFMA to be accurate and reli- able. By providing this general information, SIFMA is neither recommending investing in securities, nor providing investment advice for any investor. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment deci- sions, please consult your investment advisor regarding investment decisions. ii W H A T A R E C O R P O R A T E BONDS? Corporate bonds (also called “corporates”) are debt obligations, or IOUs, issued by privately- and publicly-owned corporations. When you buy a corpo- rate bond, you essentially lend money to the entity that issued it. In return for the loan of your funds, the issuer agrees to pay you interest and to return the original loan amount – the face value or principal - when the bond matures or is called (the “matu- rity date” or “call date”). Unlike stocks, corporate bonds do not convey an ownership interest in the issuing corporation. Companies use the funds they raise from selling bonds for a variety of purposes, from building facilities to purchasing equipment to expanding their business. Investors buy corporates for a variety of reasons: • Attractive yields. -

February 9, 2020 Falling Real Interest Rates, Rising Debt: a Free Lunch?

February 9, 2020 Falling Real Interest Rates, Rising Debt: A Free Lunch? By Kenneth Rogoff, Harvard University1 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the American Economic Association January 3 2020 meeting in San Diego in a session entitled “The United States Economy: Growth, Stagnation or New Financial Crisis?” chaired by Dominick Salvatore. The author is grateful to Molly and Dominic Ferrante Fund at Harvard University for research support. 1 With real interest rates hovering near multi-decade lows, and even below today’s slow growth rates, has higher government debt become a proverbial free lunch in many advanced countries?2 It is certainly true that low borrowing rates help justify greater government spending on high social return investment and education projects, and should make governments more relaxed about countercyclical fiscal policy, the “free lunch” perspective is an illusion that ignores most governments’ massive off-balance-sheet obligations, as well the possibility that borrowing rates could rise in a future economic crisis, even if they fell in the last one. As Lawrence Kotlikoff (2019) has long emphasized (see also Auerbach, Gokhale and Kotlikoff, 1992) 3 standard measures of government in debt have in some sense become an accounting fiction in the modern post World War II welfare state. Every advanced economy government today spends more on publicly provided old age support and pensions alone than on interest payment, and would still be doing so even if real interest rates on government debt were two percent higher. And that does not take account of other social insurance programs, most notably old-age medical care.