Larus-On-Line Harlequin Ducks, Barnegat, NJ—© N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Ecology, Conservation, and Community Responses

BIRD ECOLOGY, CONSERVATION, AND COMMUNITY RESPONSES TO LOGGING IN THE NORTHERN PERUVIAN AMAZON by NICO SUZANNE DAUPHINÉ (Under the Direction of Robert J. Cooper) ABSTRACT Understanding the responses of wildlife communities to logging and other human impacts in tropical forests is critical to the conservation of global biodiversity. I examined understory forest bird community responses to different intensities of non-mechanized commercial logging in two areas of the northern Peruvian Amazon: white-sand forest in the Allpahuayo-Mishana Reserve, and humid tropical forest in the Cordillera de Colán. I quantified vegetation structure using a modified circular plot method. I sampled birds using mist nets at a total of 21 lowland forest stands, comparing birds in logged forests 1, 5, and 9 years postharvest with those in unlogged forests using a sample effort of 4439 net-hours. I assumed not all species were detected and used sampling data to generate estimates of bird species richness and local extinction and turnover probabilities. During the course of fieldwork, I also made a preliminary inventory of birds in the northwest Cordillera de Colán and incidental observations of new nest and distributional records as well as threats and conservation measures for birds in the region. In both study areas, canopy cover was significantly higher in unlogged forest stands compared to logged forest stands. In Allpahuayo-Mishana, estimated bird species richness was highest in unlogged forest and lowest in forest regenerating 1-2 years post-logging. An estimated 24-80% of bird species in unlogged forest were absent from logged forest stands between 1 and 10 years postharvest. -

Supplementary Material

Tetraogallus caucasicus (Caucasian Snowcock) European Red List of Birds Supplementary Material The European Union (EU27) Red List assessments were based principally on the official data reported by EU Member States to the European Commission under Article 12 of the Birds Directive in 2013-14. For the European Red List assessments, similar data were sourced from BirdLife Partners and other collaborating experts in other European countries and territories. For more information, see BirdLife International (2015). Contents Reported national population sizes and trends p. 2 Trend maps of reported national population data p. 3 Sources of reported national population data p. 5 Species factsheet bibliography p. 6 Recommended citation BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Further information http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/info/euroredlist http://www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/european-red-list-birds-0 http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/europe http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/ Data requests and feedback To request access to these data in electronic format, provide new information, correct any errors or provide feedback, please email [email protected]. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds Tetraogallus caucasicus (Caucasian Snowcock) Table 1. Reported national breeding population size and trends in Europe1. Country (or Population estimate Short-term -

Volume 91 Issue 2 Mar-Apr 2014

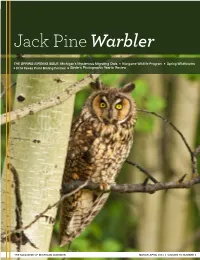

Jack Pine Warbler THE SPRING BIRDING ISSUE: Michigan’s Mysterious Migrating Owls Nongame Wildlife Program Spring Wildflowers 2014 Tawas Point Birding Festival Birder’s Photographic Year in Review THE MAGAZINE OF MICHIGAN AUDUBON MARCH-APRIL 2014 | VOLUME 91 NUMBER 2 Cover Photo Long-eared Owl Photographer: Chris Reinhold | [email protected] One day, while taking a drive to a place I normally shoot many hawks and eagles, I came across this Long-eared Owl perched on a fence post. I had heard a number of screeches coming from the CONTACT US area where the owl was hanging out and hunting, so I figured it had By mail: a family of young owls, which it did (four of them). I kept going back PO Box 15249 day after day; I think the owl finally got used to me because I was Lansing, MI 48901 able to get close enough to capture this shot and many others (find them at www.wildartphotography.ca). This image was taken at 1/100 By visiting: sec at f6.3, 500mm focal length, ISO 400 using a stabilized lens and Bengel Wildlife Center Tripod. Gear was a Canon 7D and Sigma 150-500mm lens. 6380 Drumheller Road Bath, MI 48808 Phone 517-641-4277 Fax 517-641-4279 Mon.–Fri. 9 AM–5 PM Contents EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Jonathan E. Lutz [email protected] Features Columns Departments STAFF Tom Funke 2 8 1 Conservation Director Michigan's Mysterious A Fine Kettle of Hawks Executive Director’s Letter [email protected] Migratory Owls 2013 Spring Raptor Migration Wendy Tatar 3 Program Coordinator 4 9 Calendar [email protected] Michigan’s Nongame Book Review Wildlife Program Used Books Help Birds 13 Mallory King Announcements Marketing and Communications Coordinator 7 10 New Member List [email protected] Warblers & New Waves in Chapter Spotlight Birding & 2014 Tawas Point Oakland Audubon Society Michael Caterino Birding Festival Membership Assistant 11 [email protected] Spring Wildflowers EDITOR Ephemeral: n. -

On Birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, Quantifying The

Facultad de Ciencias ACTA BIOLÓGICA COLOMBIANA Departamento de Biología http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/actabiol Sede Bogotá ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN / RESEARCH ARTICLE ZOOLOGÍA ON BIRDS OF SANTANDER-BIO EXPEDITIONS, QUANTIFYING THE COST OF COLLECTING VOUCHER SPECIMENS IN COLOMBIA Sobre las aves de las expediciones Santander-Bio, cuantificando el costo de colectar especímenes en Colombia Enrique ARBELÁEZ-CORTÉS1 *, Daniela VILLAMIZAR-ESCALANTE1 , Fernando RONDÓN-GONZÁLEZ2 1Grupo de Estudios en Biodiversidad, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. 2Grupo de Investigación en Microbiología y Genética, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. *For correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23th January 2019, Returned for revision: 26th March 2019, Accepted: 06th May 2019. Associate Editor: Diego Santiago-Alarcón. Citation/Citar este artículo como: Arbeláez-Cortés E, Villamizar-Escalante D, and Rondón-González F. On birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, quantifying the cost of collecting voucher specimens in Colombia. Acta biol. Colomb. 2020;25(1):37-60. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/abc. v25n1.77442 ABSTRACT Several scientific reasons support continuing bird collection in Colombia, a megadiverse country with modest science financing. Despite the recognized value of biological collections for the rigorous study of biodiversity, there is scarce information on the monetary costs of specimens. We present results for three expeditions conducted in Santander (municipalities of Cimitarra, El Carmen de Chucurí, and Santa Barbara), Colombia, during 2018 to collect bird voucher specimens, quantifying the costs of obtaining such material. After a sampling effort of 1290 mist net hours and occasional collection using an airgun, we collected 300 bird voucher specimens, representing 117 species from 30 families. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

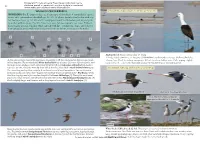

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Ecuador: the Andes & Mindo December 1

Ecuador: The Andes & Mindo December 1 – 9, 2016 Experience Ecuador’s Andean beauty and amazing bird diversity: from the hummingbirds of Yanacocha to the cloud forests of Bella Vista. Explore Antisana Volcano and search for endemics of the Chocó region; this trip is a must for those keen to explore South America. Visit the east and west sides of two branches of the Andes and bird key hotspots at Silanche, Milpe, Mindo, Guango, San Isidro, Papallacta Pass, and Antisana Volcano. Ecuador’s cloud forests host rarities like Highland Tinamou, Greater Scythebill, Bicolored Antbird, and the Sword-billed Hummingbird ― the only bird with a bill longer than its body. Savor delightful eco-lodges in forests lush with orchids, bromeliads, and butterflies, browse colorful markets, and enjoy warm Ecuadorian hospitality. Extend your trip to one of the Amazonia lodges if you choose. Tour Highlights Explore the important Yanacocha Reserve, with hummingbirds — including the amazing Sword-billed — as the star attraction Relax at the lovely Sachatamia Lodge, located on a private reserve; legendary birding is just out your door Bird a private farm, famous for views of the often difficult Giant Antpitta and Andean Cock-of-the-Rock Discover the abundant species of the lush cloud forest, 5,000 – 7,000 feet above sea level Trek the tundra-like high paramo and enjoy views of the stunning (and snow-capped) Antisana Volcano; our eyes are peeled for Andean Condor Bird and botanize in the cloud forests of San Isidro; 310 species abound Naturalist Journeys, LLC / Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 / 800.426.7781 Fax 650.471.7667www.naturalistjourneys.com / www.caligo.com [email protected] / [email protected] Tour Summary 9-Day / 8-Night Birding & Natural History Tour with Expert Local Guides $2750 from Quito Airport is Mariscal Sucre International (UIO) Itinerary Thurs., Dec. -

Ornithological Surveys in Serranía De Los Churumbelos, Southern Colombia

Ornithological surveys in Serranía de los Churumbelos, southern Colombia Paul G. W . Salaman, Thomas M. Donegan and Andrés M. Cuervo Cotinga 12 (1999): 29– 39 En el marco de dos expediciones biológicos y Anglo-Colombian conservation expeditions — ‘Co conservacionistas anglo-colombianas multi-taxa, s lombia ‘98’ and the ‘Colombian EBA Project’. Seven llevaron a cabo relevamientos de aves en lo Serranía study sites were investigated using non-systematic de los Churumbelos, Cauca, en julio-agosto 1988, y observations and standardised mist-netting tech julio 1999. Se estudiaron siete sitios enter en 350 y niques by the three authors, with Dan Davison and 2500 m, con 421 especes registrados. Presentamos Liliana Dávalos in 1998. Each study site was situ un resumen de los especes raros para cada sitio, ated along an altitudinal transect at c. 300- incluyendo los nuevos registros de distribución más m elevational steps, from 350–2500 m on the Ama significativos. Los resultados estabilicen firme lo zonian slope of the Serranía. Our principal aim was prioridad conservacionista de lo Serranía de los to allow comparisons to be made between sites and Churumbelos, y aluco nos encontramos trabajando with other biological groups (mammals, herptiles, junto a los autoridades ambientales locales con insects and plants), and, incorporating geographi cuiras a lo protección del marcizo. cal and anthropological information, to produce a conservation assessment of the region (full results M e th o d s in Salaman et al.4). A sizeable part of eastern During 14 July–17 August 1998 and 3–22 July 1999, Cauca — the Bota Caucana — including the 80-km- ornithological surveys were undertaken in Serranía long Serranía de los Churumbelos had never been de los Churumbelos, Department of Cauca, by two subject to faunal surveys. -

Ficha Informativa De Los Humedales De Ramsar (FIR) Versión 2009-2012

Ficha Informativa de los Humedales de Ramsar (FIR) versión 2009-2012 1. Nombre y dirección del compilador de la Ficha: PARA USO INTERNO DE LA OFICINA DE RAMSAR . DD MM YY Sandro Menezes Silva Conservação Internacional (CI-Brasil) R. Paraná, 32 CEP-79020-290 Designation date Site Reference Number Campo Grande - MS – Brasil [email protected] Tel: +55(67) 3326-0002 Fax: +55(67) 3326-8737 2. Fecha en que la Ficha se llenó /actualizó : Julio 2008 3. País: Brasil 4. Nombre del sitio Ramsar: Reserva Particular del Patrimonio Natural (RPPN) “Fazenda Rio Negro” 5. Designación de nuevos sitios Ramsar o actualización de los ya existentes: Esta FIR es para (marque una sola casilla) : a) Designar un nuevo sitio Ramsar o b) Actualizar información sobre un sitio Ramsar existente 6. Sólo para las actualizaciones de FIR, cambios en el sitio desde su designación o anterior actualización: 7. Mapa del sitio: a) Se incluye un mapa del sitio, con límites claramente delineados, con el siguiente formato: i) versión impresa (necesaria para inscribir el sitio en la Lista de Ramsar): Anexo 1 ; ii ) formato electrónico (por ejemplo, imagen JPEG o ArcView) iii) un archivo SIG con tablas de atributos y vectores georreferenciados sobre los límites del sitio b) Describa sucintamente el tipo de delineación de límites aplicado: El límite del Sitio Ramsar es el mismo de la RPPN Fazenda Rio Negro, reconocida oficialmente como área protegida por el gobierno de la Provincia de Mato Grosso 8. Coordenadas geográficas (latitud / longitud, en grados y minutos): Lat 19°33'2.78"S / long 56°13'27.93"O (coordenadas de la sede de la hacienda) 9. -

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo Areas, Loreto, Peru

Provisional List of Birds of the Rio Tahuauyo areas, Loreto, Peru Compiled by Carol R. Foss, Ph.D. and Josias Tello Huanaquiri, Guide Status based on expeditions from Tahuayo Logde and Amazonia Research Center TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 1. Great Tinamou Tinamus major 2. White- throated Tinamou Tinamus guttatus 3. Cinereous Tinamou Crypturellus cinereus 4. Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui 5. Undulated Tinamou Crypturellus undulates 6. Variegated Tinamou Crypturellus variegatus 7. Bartlett’s Tinamou Crypturellus bartletti ANSERIFORMES: Anhimidae 8. Horned Screamer Anhima cornuta ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 9. Muscovy Duck Cairina moschata 10. Blue-winged Teal Anas discors 11. Masked Duck Nomonyx dominicus GALLIFORMES: Cracidae 12. Spix’s Guan Penelope jacquacu 13. Blue-throated Piping-Guan Pipile cumanensis 14. Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 15. Wattled Curassow Crax globulosa 16. Razor-billed Curassow Mitu tuberosum GALLIFORMES: Odontophoridae 17. Marbled Wood-Quall Odontophorus gujanensis 18. Starred Wood-Quall Odontophorus stellatus PELECANIFORMES: Phalacrocoracidae 19. Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus PELECANIFORMES: Anhingidae 20. Anhinga Anhinga anhinga CICONIIFORMES: Ardeidae 21. Rufescent Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma lineatum 22. Agami Heron Agamia agami 23. Boat-billed Heron Cochlearius cochlearius 24. Zigzag Heron Zebrilus undulatus 25. Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax 26. Striated Heron Butorides striata 27. Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 28. Cocoi Heron Ardea cocoi 29. Great Egret Ardea alba 30. Cappet Heron Pilherodius pileatus 31. Snowy Egret Egretta thula 32. Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea CICONIIFORMES: Threskiornithidae 33. Green Ibis Mesembrinibis cayennensis 34. Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja CICONIIFORMES: Ciconiidae 35. Jabiru Jabiru mycteria 36. Wood Stork Mycteria Americana CICONIIFORMES: Cathartidae 37. Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 38. Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes burrovianus 39. -

Guia Para Observação Das Aves Do Parque Nacional De Brasília

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234145690 Guia para observação das aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília Book · January 2011 CITATIONS READS 0 629 4 authors, including: Mieko Kanegae Fernando Lima Favaro Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Bi… 7 PUBLICATIONS 74 CITATIONS 17 PUBLICATIONS 69 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Fernando Lima Favaro on 28 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Brasília - 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA Aílton C. de Oliveira Mieko Ferreira Kanegae Marina Faria do Amaral Fernando de Lima Favaro Fotografia de Aves Marcelo Pontes Monteiro Nélio dos Santos Paulo André Lima Borges Brasília, 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO APRESENTAÇÃO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA É com grande satisfação que apresento o Guia para Observação REPÚblica FEDERATiva DO BRASIL das Aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília, o qual representa um importante instrumento auxiliar para os observadores de aves que frequentam ou que Presidente frequentarão o Parque, para fins de lazer (birdwatching), pesquisas científicas, Dilma Roussef treinamentos ou em atividades de educação ambiental. Este é mais um resultado do trabalho do Centro Nacional de Pesquisa e Vice-Presidente Conservação de Aves Silvestres - CEMAVE, unidade descentralizada do Instituto Michel Temer Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) e vinculada à Diretoria de Conservação da Biodiversidade. O Centro tem como missão Ministério do Meio Ambiente - MMA subsidiar a conservação das aves brasileiras e dos ambientes dos quais elas Izabella Mônica Vieira Teixeira dependem. -

Costa Rica: the Introtour | July 2017

Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour Costa Rica: The Introtour July 15 – 25, 2017 Tour Leader: Scott Olmstead INTRODUCTION This year’s July departure of the Costa Rica Introtour had great luck with many of the most spectacular, emblematic birds of Central America like Resplendent Quetzal (photo right), Three-wattled Bellbird, Great Green and Scarlet Macaws, and Keel-billed Toucan, as well as some excellent rarities like Black Hawk- Eagle, Ochraceous Pewee and Azure-hooded Jay. We enjoyed great weather for birding, with almost no morning rain throughout the trip, and just a few delightful afternoon and evening showers. Comfortable accommodations, iconic landscapes, abundant, delicious meals, and our charismatic driver Luís enhanced our time in the field. Our group, made up of a mix of first- timers to the tropics and more seasoned tropical birders, got along wonderfully, with some spying their first-ever toucans, motmots, puffbirds, etc. on this trip, and others ticking off regional endemics and hard-to-get species. We were fortunate to have several high-quality mammal sightings, including three monkey species, Derby’s Wooly Opossum, Northern Tamandua, and Tayra. Then there were many www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 superb reptiles and amphibians, among them Emerald Basilisk, Helmeted Iguana, Green-and- black and Strawberry Poison Frogs, and Red-eyed Leaf Frog. And on a daily basis we saw many other fantastic and odd tropical treasures like glorious Blue Morpho butterflies, enormous tree ferns, and giant stick insects! TOP FIVE BIRDS OF THE TOUR (as voted by the group) 1.