A Brief Overview of the Melungeons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AAPI Community Data Needed to Assess Better Health Outcomes

CENTER FOR HEALTH EQUITY REPORT AAPI community data needed to assess better health outcomes EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report lays out an historical overview of the politicizing of the AAPI community for the purpose of distributing federal resources based on need as determined by federal data collection efforts. This report also outlines what current federal, state, local, as well as private and non-government associated data efforts entail, and the limitations associated with current efforts. Finally, this report re-emphasizes the need for continued surveillance of data collection initiatives, and greater granularity of data collection, pertaining to AAPI communities in the U.S. and its territories. and greater granularity of data collection, pertaining to AAPI communities in the U.S. and its territories. BACKGROUND At the height of the Vietnam War in 1968, a young Japanese graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley, Yuji Ichioka, banded with other students in an attempt to shut down the university in collective protest against the conflict. The demonstration was not only successful for five months, but Ichioka and his student colleagues also successfully initiated a self-determination campaign against the derogatory term, “Oriental,” then reserved for all persons of Asian descent, birthing the distinction, “Asian American,”1 which we use to this day. The United States Census Bureau’s “Asian” racial category refers to “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent...,” while “Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander” refers to “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.2” Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) collectively comprise the largest and fastest growing racial group in the U.S. -

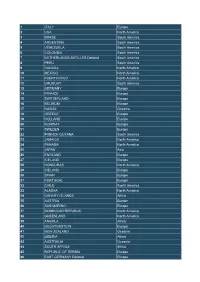

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

The Scotch-Irish in America. ' by Samuel, Swett Green

32 American Antiquarian Society. [April, THE SCOTCH-IRISH IN AMERICA. ' BY SAMUEL, SWETT GREEN. A TRIBUTE is due from the Puritan to the Scotch-Irishman,"-' and it is becoming in this Society, which has its headquar- ters in the heart of New England, to render that tribute. The story of the Scotsmen who swarmed across the nar- row body of water which separates Scotland from Ireland, in the seventeenth century, and who came to America in the eighteenth century, in large numbers, is of perennial inter- est. For hundreds of years before the beginning of the seventeenth centurj' the Scot had been going forth con- tinually over Europe in search of adventure and gain. A!IS a rule, says one who knows him \yell, " he turned his steps where fighting was to be had, and the pay for killing was reasonably good." ^ The English wars had made his coun- trymen poor, but they had also made them a nation of soldiers. Remember the "Scotch Archers" and the "Scotch (juardsmen " of France, and the delightful story of Quentin Durward, by Sir Walter Scott. Call to mind the " Scots Brigade," which dealt such hard blows in the contest in Holland with the splendid Spanish infantry which Parma and Spinola led, and recall the pikemen of the great Gustavus. The Scots were in the vanguard of many 'For iickiiowledgments regarding the sources of information contained in this paper, not made in footnotes, read the Bibliographical note at its end. ¡' 2 The Seotch-líiáh, as I understand the meaning of the lerm, are Scotchmen who emigrated to Ireland and such descendants of these emigrants as had not through intermarriage with the Irish proper, or others, lost their Scotch char- acteristics. -

Old Time Banjo

|--Compilations | |--Banjer Days | | |--01 Rippling Waters | | |--02 Johnny Don't Get Drunk | | |--03 Hand Me down My Old Suitcase | | |--04 Moonshiner | | |--05 Pass Around the Bottle | | |--06 Florida Blues | | |--07 Cuckoo | | |--08 Dixie Darling | | |--09 I Need a Prayer of Those I Love | | |--10 Waiting for the Robert E Lee | | |--11 Dead March | | |--12 Shady Grove | | |--13 Stay Out of Town | | |--14 I've Been Here a Long Long Time | | |--15 Rolling in My Sweet Baby's Arms | | |--16 Walking in the Parlour | | |--17 Rye Whiskey | | |--18 Little Stream of Whiskey (the dying Hobo) | | |--19 Old Joe Clark | | |--20 Sourwood Mountain | | |--21 Bonnie Blue Eyes | | |--22 Bonnie Prince Charlie | | |--23 Snake Chapman's Tune | | |--24 Rock Andy | | |--25 I'll go Home to My Honey | | `--banjer days | |--Banjo Babes | | |--Banjo Babes 1 | | | |--01 Little Orchid | | | |--02 When I Go To West Virginia | | | |--03 Precious Days | | | |--04 Georgia Buck | | | |--05 Boatman | | | |--06 Rappin Shady Grove | | | |--07 See That My Grave Is Kept Clean | | | |--08 Willie Moore | | | |--09 Greasy Coat | | | |--10 I Love My Honey | | | |--11 High On A Mountain | | | |--12 Maggie May | | | `--13 Banjo Jokes Over Pickin Chicken | | |--Banjo Babes 2 | | | |--01 Hammer Down Girlfriend | | | |--02 Goin' 'Round This World | | | |--03 Down to the Door:Lost Girl | | | |--04 Time to Swim | | | |--05 Chilly Winds | | | |--06 My Drug | | | |--07 Ill Get It Myself | | | |--08 Birdie on the Wire | | | |--09 Trouble on My Mind | | | |--10 Memories of Rain | | | |--12 -

The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn University Scholar Projects University Scholar Program Spring 5-1-2021 Untold Stories of the African Diaspora: The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area Shanelle A. Jones [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/usp_projects Part of the Immigration Law Commons, Labor Economics Commons, Migration Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Shanelle A., "Untold Stories of the African Diaspora: The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area" (2021). University Scholar Projects. 69. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/usp_projects/69 Untold Stories of the African Diaspora: The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area Shanelle Jones University Scholar Committee: Dr. Charles Venator (Chair), Dr. Virginia Hettinger, Dr. Sara Silverstein B.A. Political Science & Human Rights University of Connecticut May 2021 Abstract: The African Diaspora represents vastly complex migratory patterns. This project studies the journeys of English-speaking Afro-Caribbeans who immigrated to the US for economic reasons between the 1980s-present day. While some researchers emphasize the success of West Indian immigrants, others highlight the issue of downward assimilation many face upon arrival in the US. This paper explores the prospect of economic incorporation into American society for West Indian immigrants. I conducted and analyzed data from an online survey and 10 oral histories of West Indian economic migrants residing in the Greater Hartford Area to gain a broader perspective on the economic attainment of these immigrants. -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

Emerging Paradigms in Critical Mixed Race Studies G

Emerging Paradigms in Critical Mixed Race Studies G. Reginald Daniel, Laura Kina, Wei Ming Dariotis, and Camilla Fojas Mixed Race Studies1 In the early 1980s, several important unpublished doctoral dissertations were written on the topic of multiraciality and mixed-race experiences in the United States. Numerous scholarly works were published in the late 1980s and early 1990s. By 2004, master’s theses, doctoral dissertations, books, book chapters, and journal articles on the subject reached a critical mass. They composed part of the emerging field of mixed race studies although that scholarship did not yet encompass a formally defined area of inquiry. What has changed is that there is now recognition of an entire field devoted to the study of multiracial identities and mixed-race experiences. Rather than indicating an abrupt shift or change in the study of these topics, mixed race studies is now being formally defined at a time that beckons scholars to be more critical. That is, the current moment calls upon scholars to assess the merit of arguments made over the last twenty years and their relevance for future research. This essay seeks to map out the critical turn in mixed race studies. It discusses whether and to what extent the field that is now being called critical mixed race studies (CMRS) diverges from previous explorations of the topic, thereby leading to formations of new intellectual terrain. In the United States, the public interest in the topic of mixed race intensified during the 2008 presidential campaign of Barack Obama, an African American whose biracial background and global experience figured prominently in his campaign for and election to the nation’s highest office. -

American = White ? 54

1 Running Head: AMERICAN = WHITE? American = White? Thierry Devos Mahzarin R. Banaji San Diego State University Harvard University American = White? 2 Abstract In six studies, the extent to which American ethnic groups (African, Asian, and White) are associated with the national category “American” was investigated. Although strong explicit commitments to egalitarian principles were expressed (Study 1), each of five subsequent studies consistently revealed that both African and Asian Americans as groups are less associated with the national category “American” than are White Americans (Studies 2-6). Under some circumstances, a complete dissociation between mean levels of explicit beliefs and implicit responses emerged such that an ethnic minority was explicitly regarded to be more American than were White Americans (e.g., African Americans representing the U.S. in Olympic sports), but implicit measures showed the reverse pattern (Studies 3 and 4). In addition, Asian American participants themselves showed the American = White effect, although African Americans did not (Study 5). Importantly, the American = White association predicted the strength of national identity in White Americans: the greater the exclusion of Asian Americans from the category “American,” the greater the identification with being American (Study 6). Together, these studies provide evidence that to be American is implicitly synonymous with being White. American = White? 3 American = White? In 1937, the Trustees of the Carnegie Corporation of New York invited the Swedish sociologist Gunnar Myrdal to study the “Negro problem” in America. The main message from Myrdal’s now classic study was captured in the title of his book, An American Dilemma (1944). Contrary to expectations that White Americans would express prejudice without compunction, Myrdal found that even sixty years ago in the deep South, White citizens clearly experienced a moral dilemma, “an ever-raging conflict” between strong beliefs in equality and liberty for all and the reality of their actions and their history. -

Asian American and Pacific Islander Memorandum

OFFICE OF THE UNDER SECRETARY OF DEFENSE 4000 DEFENSE PENTAGON WASHINGTON, D.C. 20301-4000 PERSONNEL AND READINESS MEMORANDUM FOR: SEE DISTRIBUTION SUBJECT: Department of Defense 2018 Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month Observance The Department of Defense (DoD) joins the Nation in observance of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month during the month of May. Asian American ancestry spans all of Asia, including the Indian Subcontinent. Pacific Islanders’ origins range from Hawaii, Guam, and Samoa, to other Pacific Islands. Together with the Nation, DoD celebrates and honors the contributions of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders to the strength and defense of the United States. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have supported the U.S. military throughout our Nation’s history. Over the course of this time, more than 30 Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have earned the Medal of Honor. Today, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders remain integral to the fortitude of the DoD. Serving both in the military and civilian sector, these patriotic Americans represent more than 160,000 members of DoD’s Total Force. During this commemorative month, DoD personnel are encouraged to celebrate Asian American and Pacific Islander heritage and the many contributions of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders to the strength, security, and progress of the United States. Mr. Norvel Dillard is the DoD point of contact for this observance and can be reached by telephone at (703) 614-3397, or by email at [email protected]. -

Bluegrass/Old Time Overlap Tunes Here’S a List of Some Instrumentals Found in Both Old Time and Bluegrass Repertoires

Pegram Jam FIDDLE TUNE CHORD CHART BOOK When you learn an old time tune, you make a friend for life. A collection of accompanist charts for 450+ Old Time/Bluegrass/Celtic tunes LARGE TYPE FORMAT • INTERMEDIATE LEVEL FREE AUDIO TUNE ARCHIVE @ pegramjam.com Version 48 | August 2013 © Kirk Pickering & Susie Coleman Pegram Jam FIDDLE TUNE CHORD CHART BOOK The Pegram Jam is just that... a jam. It’s a casual, loosely organized session with a collective goal: to learn, teach and practice Old Time fiddle tunes. It’s a pretty popular place for tune lovers and we invite you to join the party via our free online audio library at PegramJam.com. We created the Pegram Jam Chord Chart Book to help rhythm and bass accompanists remember appropriate chord changes to the tunes we play at our jams. A tune can be presented at the jam by any musician who attends; our charted arrangement is generally based on that version. We’ve charted almost every song brought to the circle and added the tune to our collection. Though we strive to be accurate, you will find errors and discrepancies in opinion; however, we continually work through the songs and update the book. Please check our website for periodic updates. FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions .............................. 4 How to read our charts ................................................. 5 Alphabetical list of tunes ............................................. 6 Tunes by key .................................................................. 13 Newest additions ......................................................... -

Mexican Americans As a Paradigm for Contemporary Intra-Group Heterogeneity

Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2014 Vol. 37, No. 3, 446Á466, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.786111 Mexican Americans as a paradigm for contemporary intra-group heterogeneity Richard Alba, Toma´s R. Jime´nez and Helen B. Marrow (First submission October 2012; First published April 2013) Abstract Racialization and assimilation offer alternative perspectives on the position of immigrant-origin populations in American society. We question the adequacy of either perspective alone in the early twenty- first century, taking Mexican Americans as our case in point. Re-analysing the child sample of the Mexican American Study Project, we uncover substantial heterogeneity marked by vulnerability to racialization at one end but proximity to the mainstream at the other. This heterogeneity reflects important variations in how education, intermarriage, mixed ancestry and geographic mobility have intersected for Mexican immi- grants and their descendants over the twentieth century, and in turn shaped their ethnic identity. Finally, based on US census findings, we give reason to think that internal heterogeneity is increasing in the twenty-first century. Together, these findings suggest that future studies of immigrant adaptation in America must do a better job of accounting for hetero- geneity, not just between but also within immigrant-origin populations. Keywords: assimilation; racialization; incorporation; Mexican Americans; hetero- geneity; education. Downloaded by [171.67.216.22] at 10:40 29 January 2014 Introduction In every immigration era, certain groups are taken as emblematic of the period’s problems and successes. What the Irish were to the second half of the nineteenth century in the USA, the Eastern European Jews and Italians were to the first half of the twentieth. -

1 Centro Vasco New York

12 THE BASQUES OF NEW YORK: A Cosmopolitan Experience Gloria Totoricagüena With the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre TOTORICAGÜENA, Gloria The Basques of New York : a cosmopolitan experience / Gloria Totoricagüena ; with the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre. – 1ª ed. – Vitoria-Gasteiz : Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia = Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, 2003 p. ; cm. – (Urazandi ; 12) ISBN 84-457-2012-0 1. Vascos-Nueva York. I. Sarriugarte Doyaga, Emilia. II. Renteria Aguirre, Anna M. III. Euskadi. Presidencia. IV. Título. V. Serie 9(1.460.15:747 Nueva York) Edición: 1.a junio 2003 Tirada: 750 ejemplares © Administración de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco Presidencia del Gobierno Director de la colección: Josu Legarreta Bilbao Internet: www.euskadi.net Edita: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia - Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco Donostia-San Sebastián, 1 - 01010 Vitoria-Gasteiz Diseño: Canaldirecto Fotocomposición: Elkar, S.COOP. Larrondo Beheko Etorbidea, Edif. 4 – 48180 LOIU (Bizkaia) Impresión: Elkar, S.COOP. ISBN: 84-457-2012-0 84-457-1914-9 D.L.: BI-1626/03 Nota: El Departamento editor de esta publicación no se responsabiliza de las opiniones vertidas a lo largo de las páginas de esta colección Index Aurkezpena / Presentation............................................................................... 10 Hitzaurrea / Preface.........................................................................................