American = White ? 54

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Event Winners

Meet History -- NCAA Division I Outdoor Championships Event Winners as of 6/17/2017 4:40:39 PM Men's 100m/100yd Dash 100 Meters 100 Meters 1992 Olapade ADENIKEN SR 22y 292d 10.09 (2.0) +0.09 2017 Christian COLEMAN JR 21y 95.7653 10.04 (-2.1) +0.08 UTEP {3} Austin, Texas Tennessee {6} Eugene, Ore. 1991 Frank FREDERICKS SR 23y 243d 10.03w (5.3) +0.00 2016 Jarrion LAWSON SR 22y 36.7652 10.22 (-2.3) +0.01 BYU Eugene, Ore. Arkansas Eugene, Ore. 1990 Leroy BURRELL SR 23y 102d 9.94w (2.2) +0.25 2015 Andre DE GRASSE JR 20y 215d 9.75w (2.7) +0.13 Houston {4} Durham, N.C. Southern California {8} Eugene, Ore. 1989 Raymond STEWART** SR 24y 78d 9.97w (2.4) +0.12 2014 Trayvon BROMELL FR 18y 339d 9.97 (1.8) +0.05 TCU {2} Provo, Utah Baylor WJR, AJR Eugene, Ore. 1988 Joe DELOACH JR 20y 366d 10.03 (0.4) +0.07 2013 Charles SILMON SR 21y 339d 9.89w (3.2) +0.02 Houston {3} Eugene, Ore. TCU {3} Eugene, Ore. 1987 Raymond STEWART SO 22y 80d 10.14 (0.8) +0.07 2012 Andrew RILEY SR 23y 276d 10.28 (-2.3) +0.00 TCU Baton Rouge, La. Illinois {5} Des Moines, Iowa 1986 Lee MCRAE SO 20y 136d 10.11 (1.4) +0.03 2011 Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 24y 92d 9.89 (1.3) +0.08 Pittsburgh Indianapolis, Ind. Florida State {3} Des Moines, Iowa 1985 Terry SCOTT JR 20y 344d 10.02w (2.9) +0.02 2010 Jeff DEMPS SO 20y 155d 9.96w (2.5) +0.13 Tennessee {3} Austin, Texas Florida {2} Eugene, Ore. -

AAPI Community Data Needed to Assess Better Health Outcomes

CENTER FOR HEALTH EQUITY REPORT AAPI community data needed to assess better health outcomes EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report lays out an historical overview of the politicizing of the AAPI community for the purpose of distributing federal resources based on need as determined by federal data collection efforts. This report also outlines what current federal, state, local, as well as private and non-government associated data efforts entail, and the limitations associated with current efforts. Finally, this report re-emphasizes the need for continued surveillance of data collection initiatives, and greater granularity of data collection, pertaining to AAPI communities in the U.S. and its territories. and greater granularity of data collection, pertaining to AAPI communities in the U.S. and its territories. BACKGROUND At the height of the Vietnam War in 1968, a young Japanese graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley, Yuji Ichioka, banded with other students in an attempt to shut down the university in collective protest against the conflict. The demonstration was not only successful for five months, but Ichioka and his student colleagues also successfully initiated a self-determination campaign against the derogatory term, “Oriental,” then reserved for all persons of Asian descent, birthing the distinction, “Asian American,”1 which we use to this day. The United States Census Bureau’s “Asian” racial category refers to “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent...,” while “Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander” refers to “a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands.2” Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) collectively comprise the largest and fastest growing racial group in the U.S. -

Thomas Jefferson Day, 2006

Proc. 8001 Title 3—The President and online campaign to encourage teens to reject drug use and other nega- tive pressures. My Administration has also hosted a series of summits to educate community leaders and school officials on successful student drug testing. The struggle against alcohol abuse, drugs, and violence is a national, state, and local effort. Parents, teachers, volunteers, D.A.R.E. officers, and all those who help our young people grow into responsible, successful adults are strengthening our country and contributing to a future of hope for ev- eryone. NOW, THEREFORE, I, GEORGE W. BUSH, President of the United States of America, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and laws of the United States, do hereby proclaim April 11, 2006, as National D.A.R.E. Day. I call upon young people and all Americans to fight drug use and violence in our communities. I also urge our citizens to support the law enforcement officials, volunteers, teachers, health care professionals, and all those who work to help our children avoid drug use and violence. IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand this seventh day of April, in the year of our Lord two thousand six, and of the Independence of the United States of America the two hundred and thirtieth. GEORGE W. BUSH Proclamation 8001 of April 13, 2006 Thomas Jefferson Day, 2006 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation Today, we celebrate the birthday of Thomas Jefferson. Few individuals have shaped the course of human events as much as this proud son of Vir- ginia. -

The Strange Career of Thomas Jefferson Race and Slavery in American Memory, I94J-I99J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository History Faculty Publications History 1993 The trS ange Career of Thomas Jefferson: Race and Slavery in American Memory Edward L. Ayers University of Richmond, [email protected] Scot A. French Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/history-faculty-publications Part of the Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ayers, Edward L. and Scot A. French. "The trS ange Career of Thomas Jefferson: Race and Slavery in American Memory." In Jeffersonian Legacies, edited by Peter S. Onuf, 418-456. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAPTER I 4 The Strange Career of Thomas Jefferson Race and Slavery in American Memory, I94J-I99J SCOT A. FRENCH AND EDWARD L. AYERS For generations, the memory of Thomas Jefferson has been inseparable from his nation's memory of race and slavery. Just as Jefferson's words are invoked whenever America's ideals of democracy and freedom need an elo quent spokesman, so are his actions invoked when critics level charges of white guilt, hypocrisy, and evasion. In the nineteenth century, abolitionists used Jefferson's words as swords; slaveholders used his example as a shield. -

Duke Men's Indoor Track & Field All-Time Records

DUKE UNIVERSITY SPORTS INFORMATION Duke Athletics External Operations Phone: 919-684-2633 Press Box Phone: 919-684-4203 Box 90557 Fax: 919-688-1765 Durham, N.C. 27708 STAFF DIRECTORY Art Chase Senior Associate Director of Athletics/External Affairs Sport Responsibilities: Football Alma Mater: Guilford, 1991 Joined Duke SID: August, 2000 Art Chase Mike DeGeorge Office: 919-684-2614 Cell: 919-599-9820 Email: [email protected] Associate Director of Director of Sports Athletics/External Information Affairs Mike DeGeorge Director of Sports Information Sport Responsibilities: Men’s Basketball, Men’s Golf Alma Mater: Dayton, 2005 Joined Duke SID: November, 2017 Office: 919-668-1712 Cell: 919-384-6601 Email: [email protected] Lindy Brown Senior Associate Sports Information Director Sport Responsibilities: Women’s Basketball, Women’s Golf Alma Mater: Western Carolina, 1996 Joined Duke SID: November, 1999 Office: 919-684-2664 Cell: 919-599-9821 Email: [email protected] Kat Castner Senior Associate Sports Information Director Lindy Brown Sport Responsibilities: Football, Wrestling Kat Castner Senior Associate Sports Senior Associate Sports Alma Mater: Robert Morris, 2010 Joined Duke SID: August, 2014 Information Director Information Director Office: 919-684-8708 Cell: Email: [email protected] Meredith Rieder Associate Sports Information Director Sport Responsibilities: Men’s Soccer, Men’s Lacrosse Alma Mater: Denison, 2002 Joined Duke SID: August, 2008 Office: 919-684-3328 Cell: 919-812-6741 Email: [email protected] Josh Foster Assistant Sports -

Fifth Grade Patriot Program 2019-2020

Fifth Grade Patriot Program 2019-2020 Name ____________________ Teacher___________________ Fifth Grade Patriot Program Name____________________ Teacher_________________________ Testing will occur from 8:30 – 9:00 a.m. each morning in the Library. Timeline Actual of Completion Steps to Patriots Completion Date Anytime Between 1._________ 1. Name and label 50 states with 80% accuracy November and March 2._________ 2. Complete a Community Service Project November 3.Bill of Rights 1. Flag Etiquette quiz December 2. Memorize and recite versus 1 of the Star Spangled Banner January Presidential Report Choose any TWO of the following: Anytime • Landmarks & memorials between • Interview a Patriot February - • Timeline Revolution March • State poster • American Creed Work must be completed by April 3, 2020 2 Fifth Grade Patriot Program Requirement Details 1. Name and label 50 states with 80% accuracy. (Pages 6-10) • Must be completed in one sitting • May use any combination of spelling and postal codes • Test may be retaken as needed 2. Pictorial Representation of the Bill of Rights • Read the Bill of Rights. • Then create a legal size poster (8 ½ x 14), PowerPoint presentation (which is to be printed out), or booklet presenting the Bill of Rights in symbolic form. • Include an illustration as well as a brief summary of the each amendment artistically. • Use drawings, cut-out pictures, or photographs, and in your own words, explain what each amendment means to you. http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/bill_of_rights_transcript.html 4. Flag -

The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn University Scholar Projects University Scholar Program Spring 5-1-2021 Untold Stories of the African Diaspora: The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area Shanelle A. Jones [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/usp_projects Part of the Immigration Law Commons, Labor Economics Commons, Migration Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Shanelle A., "Untold Stories of the African Diaspora: The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area" (2021). University Scholar Projects. 69. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/usp_projects/69 Untold Stories of the African Diaspora: The Lived Experiences of Black Caribbean Immigrants in the Greater Hartford Area Shanelle Jones University Scholar Committee: Dr. Charles Venator (Chair), Dr. Virginia Hettinger, Dr. Sara Silverstein B.A. Political Science & Human Rights University of Connecticut May 2021 Abstract: The African Diaspora represents vastly complex migratory patterns. This project studies the journeys of English-speaking Afro-Caribbeans who immigrated to the US for economic reasons between the 1980s-present day. While some researchers emphasize the success of West Indian immigrants, others highlight the issue of downward assimilation many face upon arrival in the US. This paper explores the prospect of economic incorporation into American society for West Indian immigrants. I conducted and analyzed data from an online survey and 10 oral histories of West Indian economic migrants residing in the Greater Hartford Area to gain a broader perspective on the economic attainment of these immigrants. -

Emerging Paradigms in Critical Mixed Race Studies G

Emerging Paradigms in Critical Mixed Race Studies G. Reginald Daniel, Laura Kina, Wei Ming Dariotis, and Camilla Fojas Mixed Race Studies1 In the early 1980s, several important unpublished doctoral dissertations were written on the topic of multiraciality and mixed-race experiences in the United States. Numerous scholarly works were published in the late 1980s and early 1990s. By 2004, master’s theses, doctoral dissertations, books, book chapters, and journal articles on the subject reached a critical mass. They composed part of the emerging field of mixed race studies although that scholarship did not yet encompass a formally defined area of inquiry. What has changed is that there is now recognition of an entire field devoted to the study of multiracial identities and mixed-race experiences. Rather than indicating an abrupt shift or change in the study of these topics, mixed race studies is now being formally defined at a time that beckons scholars to be more critical. That is, the current moment calls upon scholars to assess the merit of arguments made over the last twenty years and their relevance for future research. This essay seeks to map out the critical turn in mixed race studies. It discusses whether and to what extent the field that is now being called critical mixed race studies (CMRS) diverges from previous explorations of the topic, thereby leading to formations of new intellectual terrain. In the United States, the public interest in the topic of mixed race intensified during the 2008 presidential campaign of Barack Obama, an African American whose biracial background and global experience figured prominently in his campaign for and election to the nation’s highest office. -

Stanford Cross Country Course

STANFORD ATHLETICS A Tradition of Excellence 116 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship award winners, including 10 in 2007-08. 109 National Championships won by Stanford teams since 1926. 95 Stanford student-athletes who earned All-America status in 2007-08. 78 NCAA Championships won by Stanford teams since 1980. 48 Stanford-affiliated athletes and coaches who represented the United States and seven other countries in the Summer Olympics held in Beijing, including 12 current student-athletes. 32 Consecutive years Stanford teams have won at least one national championship. 31 Stanford teams that advanced to postseason play in 2007-08. 19 Different Stanford teams that have won at least one national championship. 18 Stanford teams that finished ranked in the Top 10 in their respective sports in 2007-08. 14 Consecutive U.S. Sports Academy Directors’ Cups. 14 Stanford student-athletes who earned Academic All-America recognition in 2007-08. 9 Stanford student-athletes who earned conference athlete of the year honors in 2007-08. 8 Regular season conference championships won by Stanford teams in 2007-08. 6 Pacific-10 Conference Scholar Athletes of the Year Awards in 2007-08. 5 Stanford teams that earned perfect scores of 1,000 in the NCAA’s Academic Progress Report Rate in 2007-08. 3 National Freshmen of the Year in 2007-08. 3 National Coach of the Year honors in 2007-08. 2 National Players of the Year in 2007-08. 2 National Championships won by Stanford teams in 2007-08 (women’s cross country, synchronized swimming). 1 Walter Byers Award Winner in 2007-08. -

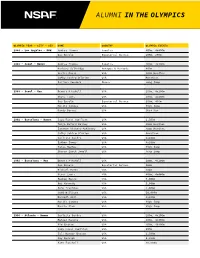

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

2019 World Championships Statistics - Men’S 110Mh by K Ken Nakamura

2019 World Championships Statistics - Men’s 110mH by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Doha: 1) If Shubenkov wins silver, he will join Jackson and Liu as one of the hurdlers with complete set of medals. 2) Can McLeod or Shubenkov become 4 th hurdler to win 110mH at WC twice? Summary: All time Performance List at the World Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 12. 91 0.5 Colin Jackson GBR 1 Stuttgart 1993 2 2 12.93 0.0 Allen Johnson USA 1 Athinai 1997 3 3 12.95 1.7 Liu Xiang CHN 1 Osaka 2007 4 4 12.98 0.2 Sergey Shubenkov RUS 1 Beijing 2015 5 5 12.99 1.7 Terrence Trammell USA 2 Osaka 2007 6 6 13.00 0.5 Tony Jarrett GBR 2 Stuttgart 1993 6 13.00 -0.1 Allen Johnson 1 Göteborg 1995 6 7 13.00 0.3 David Oliver USA 1 Moskva 2013 9 8 13.02 1.7 David Payne USA 3 Osaka 2007 10 9 13.03 0.2 Hansle Parchment JAM 2 Beijing 2015 Margin of Victory Difference time Name Nat Venue Year Max 0.13 second 13.00 David Oliver USA Moskva 2013 0.12 second 12.93 Allen Johnson USA Athinai 1997 0.11 second 13.16 Jason Richardson USA Daegu 2011 0.10 second 13.04 Omar McLeod JAM London 2017 0.09second 12.91 Colin Jackson GBR Stuttgart 1993 Min 0.00s econd 13.06 Greg Foster USA Tokyo 1991 0.01 second 13.14 Ryan Brathwaite BAR Berlin 2009 Best Marks for Places in the World Championships Pos Time wind Name Nat Venue Year 1 12.91 0.5 Colin Jackson GBR Stuttgart 1993 2 12.99 1.7 Terrence Trammell USA Osaka 2007 13.00 0.5 Tony Jarrett GBR Stuttgart 1993 3 13.02 1.7 David Payne USA Osaka 2007 4 13.13 -0.2 Dominique Arnold USA Helsinki 2005 Multiple Medalists: Allen Johnson (USA): 1995, 1997, 2001, 2003 Colin Jackson (GBR): 1993, 1999 Greg Foster (USA): 1983, 1987, 1991 All time Performance List at the World Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 12. -

Tom Black Track Records

TENNESSEE TRACK & FIELD TOM BLACK TRACK RECORDS WOMEN’S RECORDS MEN’S RECORDS EVENT MARK NAME AFFILIATION DATE EVENT MARK NAME AFFILIATION DATE 100m 10.92 Aleia Hobbs LSU 5-13-18 100m 9.8h Jeff Phillips Athletics West 5-22-82 200m 22.17 Merlene Ottey L.A. Naturite 6-20-82 10.02 Michael Green adidas 4-11-97 400m 50.24 Maicel Malone Asics International TC 6-17-94 200m 20.06 Justin Gatlin Tennessee 4-12-02 800m 2:00.27 Inez Turner SW Texas State 6-02-95 400m 44.28 Nathon Allen Auburn 5-13-18 1500m 4:03.37 Mary Decker-Tabb Athletics West 6-20-82 800m 1:44.85 David Patrick Athletics West 6-21-83 3000m 8:52.26 Brenda Webb Athletics West 5-21-83 1,500m 3:34.92 Steve Scott Sub 4 TC 6-20-82 5000m 15:22.76 Brenda Webb Team Adidas 4-13-84 Mile 3:57.7 Marty Liquori Villanova 6-21-69 10,000m 32:23.76 Olga Appell Reebok RC 6-17-94 3,000m 8:14.01 Jacob Choge Middle Tennessee 3-25-17 100mH 12.40 J. Camacho-Quinn Kentucky 5-13-18 Steeple 8:21.48 Jim Svenoy Texas-El Paso 6-2-95 400mH 52.75 Sydney McLaughlin Kentucky 5-13-18 5,000m 13:20.39 Todd Williams adidas 4-11-97 2000m SC 6:58.85 Gina Wilbanks Athletes in Action USA 6-17-94 10,000m 27:25.82 Simon Chemoiywo Kenya 4-6-95 3000m SC 10:04.33 Ebba Stenbeck Toledo 5-27-06 5,000m Walk 20:41.00 Jim Heiring Unattached 4-10-81 10,000m walk 45:01.96 Teresa Vaill Unattached 6-16-94 10,000m Walk 46:50.6 Timothy Lewis New York AC 6-17-80 20,000m walk 1:28:35.87 Allen James Athletes in Action 6-13-94 4x100m Relay 42.05 ---------------- LSU 5-13-18 110mH 13.15 Grant Holloway Florida 5-13-18 (Mikiah Brisco, Kortnei Johnson, Rachel Misher, Aleia Hobbs) 400mH 48.38 Danny Harris Athletic West 5-23-87 4x200m Relay 1:30.76 ---------------- Kentucky 4-14-18 (Sydney McLaughlin, Jasmin Camacho-Quinn, Kayelle Clarke, Celera Barnes) 4x100mR 38.08 ---------------- America’s Team 4-14-18 4x400m Relay 3:25.99 ---------------- Kentucky 5-13-18 (Christian Coleman, Justin Gatlin, Ronnie Baker, Mike Rogers) (Faith Ross, J.