Non-Eucalypt Forest and Woodland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blue Tier Reserve Background Report 2016File

Background Report Blue Tier Reserve www.tasland.org.au Tasmanian Land Conservancy (2016). The Blue Tier Reserve Background Report. Tasmanian Land Conservancy, Tasmania Australia. Copyright ©Tasmanian Land Conservancy The views expressed in this report are those of the Tasmanian Land Conservancy and not the Federal Government, State Government or any other entity. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgment of the sources and no commercial usage or sale. Requests and enquires concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Tasmanian Land Conservancy. Front Image: Myrtle rainforest on Blue Tier Reserve - Andy Townsend Contact Address Tasmanian Land Conservancy PO Box 2112, Lower Sandy Bay, 827 Sandy Bay Road, Sandy Bay TAS 7005 | p: 03 6225 1399 | www.tasland.org.au Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 1 Acronyms and Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Location and Access ................................................................................................................................ 4 Bioregional Values and Reserve Status .................................................................................................. -

For Use by Major Mitchell's Cockatoo (Lophochroa Leadbeateri) in Pine Plains, Wyperfeld National Park

Simulating natural cavities in Slender Cypress Pine (Callitris gracilis murrayensis) for use by Major Mitchell’s Cockatoo (Lophochroa leadbeateri leadbeateri): A report to the Department of Environment and Primary Industries Report Title: “Simulating natural cavities in Slender Cypress Pine (Callitris gracilis murrayensis) for use by Major Mitchell’s Cockatoo (Lophochroa leadbeateri leadbeateri): A report to the Department of Environment and Primary Industries.” Prepared by: Dr Victor G. Hurley Senior Strategic Fire and Biodiversity Officer Department of Environment and Primary Industries 308-390 Koorlong Ave Irymple VIC 3498 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 5051 4610 And Grant J. Harris Ironbark Environmental Arboriculture Charles Street Fitzroy Melbourne VIC 3065 ABN: 14 667 974 300 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0415 607 375 Report Status: Final 21 December 2014 The State of Victoria Department of Environment and Primary Industries Melbourne 2014 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. This document may be cited as: Hurley, V.G. and Harris, G.J., (2014) “Simulating natural cavities in Slender Cypress Pine (Callitris gracilis murrayensis) for use by Major Mitchell’s Cockatoo (Lophochroa leadbeateri leadbeateri): A report to the Department of Environment and Primary Industries.” Cover photographs: Hauling new cavity cover plate with the elevated work platform (Grant Harris ©). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project was funded by the Victorian Environmental Partnerships Program (VEPP) in 2013-15. Thanks go to David Christian and Matthew Baker for arranging logistical support and access to Parks Victoria facilities. Much appreciation to Ewan Murray who worked in the field in collecting and recording data and capably wielding the chainsaw and chipper and for field and occasional ambulance assistance. -

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea PROTECTING BIODIVERSITY ON PRIVATE LAND SERIES Wattles of the City of Whittlesea Over a dozen species of wattle are indigenous to the City of Whittlesea and many other wattle species are commonly grown in gardens. Most of the indigenous species are commonly found in the forested hills and the native forests in the northern parts of the municipality, with some species persisting along country roadsides, in smaller reserves and along creeks. Wattles are truly amazing • Wattles have multiple uses for Australian plants indigenous peoples, with most species used for food, medicine • There are more wattle species than and/or tools. any other plant genus in Australia • Wattle seeds have very hard coats (over 1000 species and subspecies). which mean they can survive in the • Wattles, like peas, fix nitrogen in ground for decades, waiting for a the soil, making them excellent cool fire to stimulate germination. for developing gardens and in • Australia’s floral emblem is a wattle: revegetation projects. Golden Wattle (Acacia pycnantha) • Many species of insects (including and this is one of Whittlesea’s local some butterflies) breed only on species specific species of wattles, making • In Victoria there is at least one them a central focus of biodiversity. wattle species in flower at all times • Wattle seeds and the insects of the year. In the Whittlesea attracted to wattle flowers are an area, there is an indigenous wattle important food source for most bird in flower from February to early species including Black Cockatoos December. and honeyeaters. Caterpillars of the Imperial Blue Butterfly are only found on wattles RB 3 Basic terminology • ‘Wattle’ = Acacia Wattle is the common name and Acacia the scientific name for this well-known group of similar / related species. -

Wild Mersey Mountain Bike Development

Wild Mersey Mountain Bike Development Natural Values Report Warrawee Conservation Area through to Railton Prepared for : Kentish Council and Latrobe Council Report prepared by: Matt Rose Natural State PO Box 139, Ulverstone, TAS, 7315 www.naturalstate.com.au 1 | NATURAL STATE – PO Box 139, Ulverstone TAS 7315. Mobile: 0437 971 144 www.naturalstate.com.au Table of contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Description of the proposed development activities ...................................................................... 6 1.3 Description of the study areas ............................................................................................................ 8 1.4 The Warrawee Conservation Area ..................................................................................................... 8 1.5 Warrawee to Railton trail ..................................................................................................................... 8 2 Methodology .............................................................................................................................................. -

Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area

Appendix 4 1 World Heritage Values of the Tasmanian Wilderness 1.1 Note that the Department of the Environment's website states that: A draft Statement of Outstanding Universal Value which will take into account the new areas added in 2013 is expected to be considered by the World Heritage Committee in 2014. Outstanding Universal Value 1.2 The Tasmanian Wilderness is an extensive, wild, beautiful temperate land where cultural heritage of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people is preserved. 1.3 It is one of the three largest temperate wilderness areas remaining in the Southern Hemisphere. The region is home to some of the deepest and longest caves in Australia. It is renowned for its diversity of flora, and some of the longest lived trees and tallest flowering plants in the world grow in the area. The Tasmanian Wilderness is a stronghold for several animals that are either extinct or threatened on mainland Australia. 1.4 In the southwest Aboriginal people developed a unique cultural tradition based on a specialized stone and bone toolkit that enabled the hunting and processing of a single prey species (Bennett's wallaby) that provided nearly all of their dietary protein and fat. Extensive limestone cave systems contain rock art sites that have been dated to the end of the Pleistocene period. Southwest Tasmanian Aboriginal artistic expression during the last Ice Age is only known from the dark recesses of limestone caves. 1.5 The Tasmanian Wilderness was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1982 and extended in 1989, 2010, 2012 and again in 2013. -

Vegetation Benchmarks Rainforest and Related Scrub

Vegetation Benchmarks Rainforest and related scrub Eucryphia lucida Vegetation Condition Benchmarks version 1 Rainforest and Related Scrub RPW Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland: Sphagnum peatland facies Community Description: Athrotaxis cupressoides (5–8 m) forms small woodland patches or appears as copses and scattered small trees. On the Central Plateau (and other dolerite areas such as Mount Field), broad poorly– drained valleys and small glacial depressions may contain scattered A. cupressoides trees and copses over Sphagnum cristatum bogs. In the treeless gaps, Sphagnum cristatum is usually overgrown by a combination of any of Richea scoparia, R. gunnii, Baloskion australe, Epacris gunnii and Gleichenia alpina. This is one of three benchmarks available for assessing the condition of RPW. This is the appropriate benchmark to use in assessing the condition of the Sphagnum facies of the listed Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland community (Schedule 3A, Nature Conservation Act 2002). Benchmarks: Length Component Cover % Height (m) DBH (cm) #/ha (m)/0.1 ha Canopy 10% - - - Large Trees - 6 20 5 Organic Litter 10% - Logs ≥ 10 - 2 Large Logs ≥ 10 Recruitment Continuous Understorey Life Forms LF code # Spp Cover % Immature tree IT 1 1 Medium shrub/small shrub S 3 30 Medium sedge/rush/sagg/lily MSR 2 10 Ground fern GF 1 1 Mosses and Lichens ML 1 70 Total 5 8 Last reviewed – 2 November 2016 Tasmanian Vegetation Monitoring and Mapping Program Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment http://www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au/tasveg RPW Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland: Sphagnum facies Species lists: Canopy Tree Species Common Name Notes Athrotaxis cupressoides pencil pine Present as a sparse canopy Typical Understorey Species * Common Name LF Code Epacris gunnii coral heath S Richea scoparia scoparia S Richea gunnii bog candleheath S Astelia alpina pineapple grass MSR Baloskion australe southern cordrush MSR Gleichenia alpina dwarf coralfern GF Sphagnum cristatum sphagnum ML *This list is provided as a guide only. -

Edition 2 from Forest to Fjaeldmark the Vegetation Communities Highland Treeless Vegetation

Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark The Vegetation Communities Highland treeless vegetation Richea scoparia Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark 1 Highland treeless vegetation Community (Code) Page Alpine coniferous heathland (HCH) 4 Cushion moorland (HCM) 6 Eastern alpine heathland (HHE) 8 Eastern alpine sedgeland (HSE) 10 Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) 12 Western alpine heathland (HHW) 13 Western alpine sedgeland/herbland (HSW) 15 General description Rainforest and related scrub, Dry eucalypt forest and woodland, Scrub, heathland and coastal complexes. Highland treeless vegetation communities occur Likewise, some non-forest communities with wide within the alpine zone where the growth of trees is environmental amplitudes, such as wetlands, may be impeded by climatic factors. The altitude above found in alpine areas. which trees cannot survive varies between approximately 700 m in the south-west to over The boundaries between alpine vegetation communities are usually well defined, but 1 400 m in the north-east highlands; its exact location depends on a number of factors. In many communities may occur in a tight mosaic. In these parts of Tasmania the boundary is not well defined. situations, mapping community boundaries at Sometimes tree lines are inverted due to exposure 1:25 000 may not be feasible. This is particularly the or frost hollows. problem in the eastern highlands; the class Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) is used in There are seven specific highland heathland, those areas where remote sensing does not provide sedgeland and moorland mapping communities, sufficient resolution. including one undifferentiated class. Other highland treeless vegetation such as grasslands, herbfields, A minor revision in 2017 added information on the grassy sedgelands and wetlands are described in occurrence of peatland pool complexes, and other sections. -

Kunzea Template

June 2020 A Message from the President Debbie Jerkovic It has been several months since we have been able will be welcome to come and collect your orders. I to meet, and there is no sign of when we will be able to would be happy to show you around my garden and in the future. I don’t know about you, but this has provide tea and coffee, but will have to insist that we provided a wonderful opportunity to get stuck into maintain social distancing at all �mes. some gardening, especially given the great weather we Chris Fletcher is nowhere near as far away as Phil, so have been having. members are asked to contact Chris on 0419 331 325 to Our Commi�ee recently met via Zoom (which was discuss availability of various plants. Once their orders challenging and fun), and discussed various things are placed, members are invited to collect their plants including how to best support our membership. from Chris's nursery in Yarra Glen. Something which many of us have been missing is Another idea was to encourage members to contact access to Chris Fletcher’s plants at our monthly APS Yarra Yarra (Miriam Ford on 0409 600 644) regarding mee�ngs. This sparked discussion about how best to any plants remaining from their recent online sale. Barry support various growers, and it was decided to circulate Ellis was advised that there are s�ll a lot of prostantheras several plant lists (reproduced later in this newsle�er). and some westringias available which might appeal to If there are any plants on Phil’s list which interest our Mint Bush aficionados. -

Introduction Methods Results

Papers and Proceedings Royal Society ofTasmania, Volume 1999 103 THE CHARACTERISTICS AND MANAGEMENT PROBLEMS OF THE VEGETATION AND FLORA OF THE HUNTINGFIELD AREA, SOUTHERN TASMANIA by J.B. Kirkpatrick (with two tables, four text-figures and one appendix) KIRKPATRICK, J.B., 1999 (31:x): The characteristics and management problems of the vegetation and flora of the Huntingfield area, southern Tasmania. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 133(1): 103-113. ISSN 0080-4703. School of Geography and Environmental Studies, University ofTasmania, GPO Box 252-78, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001. The Huntingfield area has a varied vegetation, including substantial areas ofEucalyptus amygdalina heathy woodland, heath, buttongrass moorland and E. amygdalina shrubbyforest, with smaller areas ofwetland, grassland and E. ovata shrubbyforest. Six floristic communities are described for the area. Two hundred and one native vascular plant taxa, 26 moss species and ten liverworts are known from the area, which is particularly rich in orchids, two ofwhich are rare in Tasmania. Four other plant species are known to be rare and/or unreserved inTasmania. Sixty-four exotic plantspecies have been observed in the area, most ofwhich do not threaten the native biodiversity. However, a group offire-adapted shrubs are potentially serious invaders. Management problems in the area include the maintenance ofopen areas, weed invasion, pathogen invasion, introduced animals, fire, mechanised recreation, drainage from houses and roads, rubbish dumping and the gathering offirewood, sand and plants. Key Words: flora, forest, heath, Huntingfield, management, Tasmania, vegetation, wetland, woodland. INTRODUCTION species with the most cover in the shrub stratum (dominant species) was noted. If another species had more than half The Huntingfield Estate, approximately 400 ha of forest, the cover ofthe dominant one it was noted as a codominant. -

NLM Leptospermum Lanigerum – Melaleuca Squarrosa Swamp Forest

Vegetation Condition Benchmarks version 3 Non-Eucalypt Forest and Woodland NLM Leptospermum lanigerum – Melaleuca squarrosa swamp forest Community Description: Leptospermum lanigerum – Melaleuca squarrosa swamp forests dominated by Leptospermum lanigerum and/or Melaleuca squarrosa are common in the north-west and west and occur occasionally in the north-east and east where L. lanigerum usually predominates. There are also extensive tracts on alluvial flats of the major south-west rivers. The forests are dominated by various mixtures of L. lanigerum and M. squarrosa but with varying lesser amounts of various species of Acacia and rainforest species also present. Trees are usually > 8 m in height. Benchmarks: Length Component Cover % Height (m) DBH (cm) #/ha (m)/0.1 ha Canopy 70% - - - Large Trees - 10 25 800 Organic Litter 40% - Logs ≥ 10 - 20 Large Logs ≥ 12.5 Recruitment Episodic Understorey Life Forms LF code # Spp Cover % Tree or large shrub T 4 20 Medium shrub/small shrub S 3 15 Herbs and orchids H 5 5 Grass G 1 1 Large sedge/rush/sagg/lily LSR 1 1 Medium to small sedge/rush/sagg/lily MSR 2 1 Ground fern GF 2 5 Tree fern TF 1 5 Scrambler/Climber/Epiphytes SCE 2 5 Mosses and Lichens ML 1 20 Total 10 22 Last reviewed – 5 July 2016 Tasmanian Vegetation Monitoring and Mapping Program Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment http://www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au/tasveg NLM Leptospermum lanigerum – Melaleuca squarrosa swamp forest Species lists: Canopy Tree Species Common Name Notes Leptospermum lanigerum woolly teatree Melaleuca -

Phytophthora Resistance and Susceptibility Stock List

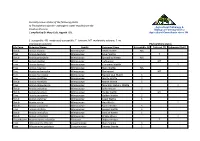

Currently known status of the following plants to Phytophthora species - pathogenic water moulds from the Agricultural Pathology & Kingdom Protista. Biological Farming Service C ompiled by Dr Mary Cole, Agpath P/L. Agricultural Consultants since 1980 S=susceptible; MS=moderately susceptible; T= tolerant; MT=moderately tolerant; ?=no information available. Phytophthora status Life Form Botanical Name Family Common Name Susceptible (S) Tolerant (T) Unknown (UnK) Shrub Acacia brownii Mimosaceae Heath Wattle MS Tree Acacia dealbata Mimosaceae Silver Wattle T Shrub Acacia genistifolia Mimosaceae Spreading Wattle MS Tree Acacia implexa Mimosaceae Lightwood MT Tree Acacia leprosa Mimosaceae Cinnamon Wattle ? Tree Acacia mearnsii Mimosaceae Black Wattle MS Tree Acacia melanoxylon Mimosaceae Blackwood MT Tree Acacia mucronata Mimosaceae Narrow Leaf Wattle S Tree Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Shrub Acacia myrtifolia Mimosaceae Myrtle Wattle S Tree Acacia obliquinervia Mimosaceae Mountain Hickory Wattle ? Shrub Acacia oxycedrus Mimosaceae Spike Wattle S Shrub Acacia paradoxa Mimosaceae Hedge Wattle MT Tree Acacia pycnantha Mimosaceae Golden Wattle S Shrub Acacia sophorae Mimosaceae Coast Wattle S Shrub Acacia stricta Mimosaceae Hop Wattle ? Shrubs Acacia suaveolens Mimosaceae Sweet Wattle S Tree Acacia ulicifolia Mimosaceae Juniper Wattle S Shrub Acacia verniciflua Mimosaceae Varnish wattle S Shrub Acacia verticillata Mimosaceae Prickly Moses ? Groundcover Acaena novae-zelandiae Rosaceae Bidgee-Widgee T Tree Allocasuarina littoralis Casuarinaceae Black Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina paludosa Casuarinaceae Swamp Sheoke S Tree Allocasuarina verticillata Casuarinaceae Drooping Sheoak S Sedge Amperea xipchoclada Euphorbaceae Broom Spurge S Grass Amphibromus neesii Poaceae Swamp Wallaby Grass ? Shrub Aotus ericoides Papillionaceae Common Aotus S Groundcover Apium prostratum Apiaceae Sea Celery MS Herb Arthropodium milleflorum Asparagaceae Pale Vanilla Lily S? Herb Arthropodium strictum Asparagaceae Chocolate Lily S? Shrub Atriplex paludosa ssp. -

NLE Leptospermum Forest: Coastal Facies

Vegetation Condition Benchmarks version 2 Non-Eucalypt Forest and Woodland NLE Leptospermum forest: coastal facies Community Description: Leptospermum forest is dominated by one or more of Leptospermum lanigerum, L. scoparium, L. glaucescens or L. nitidum (5 – 10 m) with semi-closed or closed canopies. Mid and ground layers may be sparsely shrubby and sedgy, or the ground may be bare or covered by deep litter. The coastal facies of NLE has L. glaucescens and sometimes L. scoparium in the canopy and may be diverse and uneven in height where it has suffered patchy effects of fire or windthrow. A minor facies dominated by Leptospermum lanigerum and Acacia melanoxylon in coastal swamps is included. This benchmark is one of 2 benchmarks available to assess the condition of NLE. Benchmarks: Length Component Cover % Height (m) DBH (cm) #/ha (m)/0.1 ha Canopy 70% - - - Large Trees - 80 25 1000 Organic Litter 40% - Logs ≥ 10 - 3 Large Logs ≥ 12.5 Recruitment Episodic Understorey Life Forms LF code # Spp Cover % Tree or large shrub T 4 10 Medium shrub/small shrub S 5 10 Prostrate shrub PS 2 5 Herbs and orchids H 1 1 Medium to small sedge/rush/sagg/lily MSR 1 5 Ground fern GF 1 1 Scrambler/Climber/Epiphytes SCE 2 1 Total 7 16 Last reviewed – 5 July 2016 Tasmanian Vegetation Monitoring and Mapping Program Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment http://www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au/tasveg NLE Leptospermum forest: coastal facies Species lists: Canopy Tree Species Common Name Notes Acacia melanoxylon blackwood Leptospermum scoparium common teatree Leptospermum lanigerum woolly teatree Leptospermum glaucescens smoky teatree Leptospermum nitidum shiny teatree Typical Understorey Species * Common Name LF Code Acacia spp.