Apotropaic” Tactics in the Matthean Temptation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalm 89-93: Christ Our New King June 6, 2021 Message: Take a Few

Psalm 89-93: Christ Our New King June 6, 2021 Message: Take a few moments to review the message notes from Sunday. What was your main takeaway from this message? Digging Deeper: Small Group Discussion 1.) What stood out to you? 2.) (Psalm 89) From the people’s perspective… their reality did not align with all of God’s promises. What happens when your reality fails to align with what you know to be true about God? 3.) (Psalm 90) In verse 12, what do you think it means when Moses says, “Teach us to number our days so that we may gain a heart of wisdom.”? 4.) (Psalm 91) God is our protection in verses 9 and 10, is God’s protection available to everyone? 5.) (Psalm 91:10) Does God’s protection mean Christians are immune from all harm? 6.) Satan quotes verse 11 to Jesus in the wilderness (Luke 4:9-12). The devil would like us to think that God’s promises have failed especially if He lets us suffer. Where does verse 15 say God will be? 7.) When the Israelites were tested in the wilderness they fell for Satan’s temptations. When Jesus was tested by Satan in the wilderness, He resisted temptation. What type of guidance does he model for us? 8.) (Psalm 92) This chapter is titled “A Song for the Sabbath Day.” It was written to be sung in community on the sabbath day. What do verses 1-4 teach us about praising God? 9.) (Psalm 93) This chapter reminds us the Lord reigns over all. -

![7] Arise, O Lord; Save Me, O My God: for Thou Hast Smitten All Mine Enemies Upon the Cheek Bone; Thou Hast Broken the Teeth of the Ungodly](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0336/7-arise-o-lord-save-me-o-my-god-for-thou-hast-smitten-all-mine-enemies-upon-the-cheek-bone-thou-hast-broken-the-teeth-of-the-ungodly-10336.webp)

7] Arise, O Lord; Save Me, O My God: for Thou Hast Smitten All Mine Enemies Upon the Cheek Bone; Thou Hast Broken the Teeth of the Ungodly

The World Is A Dangerous Place, But God Will Be Our Protection Psalm 3:1-5 KJV Lord, how are they increased that trouble me! Many are they that rise up against me. [2] Many there be which say of my soul, There is no help for him in God. Selah. [3] But Thou, O Lord, art a shield for me; my glory, and the lifter up of mine head. [4] I cried unto the Lord with my voice, and He heard me out of His holy hill. Selah. [5] I laid me down and slept; I awaked; for the Lord sustained me. David's son, Absalom, was trying to kill him; and David was running for his life when he sang this song. David was a man that knew that his God would keep him protected, if he believed in God's protection. Today I want you to see that God will protect you as well, if you believe for it. You do not have to fear being destroyed by anything, if you believe that God is your shield. In verse three, David declared that the Lord was his shield. A shield separates you from danger. Let's look at Ephesians 6:16 KJV Above all, taking the shield of faith, wherewith ye shall be able to quench all the fiery darts of the wicked. Notice that faith is declared to be a shield in this verse; and in Psalms 3:3, the Lord is David's shield. I believe if we have faith in the Lord protecting us, He becomes our shield. -

The Psalms As Hymns in the Temple of Jerusalem Gary A

4 The Psalms as Hymns in the Temple of Jerusalem Gary A. Rendsburg From as far back as our sources allow, hymns were part of Near Eastern temple ritual, with their performers an essential component of the temple functionaries. 1 These sources include Sumerian, Akkadian, and Egyptian texts 2 from as early as the third millennium BCE. From the second millennium BCE, we gain further examples of hymns from the Hittite realm, even if most (if not all) of the poems are based on Mesopotamian precursors.3 Ugarit, our main source of information on ancient Canaan, has not yielded songs of this sort in 1. For the performers, see Richard Henshaw, Female and Male: The Cu/tic Personnel: The Bible and Rest ~(the Ancient Near East (Allison Park, PA: Pickwick, 1994) esp. ch. 2, "Singers, Musicians, and Dancers," 84-134. Note, however, that this volume does not treat the Egyptian cultic personnel. 2. As the reader can imagine, the literature is ~xtensive, and hence I offer here but a sampling of bibliographic items. For Sumerian hymns, which include compositions directed both to specific deities and to the temples themselves, see Thorkild Jacobsen, The Harps that Once ... : Sumerian Poetry in Translation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), esp. 99-142, 375--444. Notwithstanding the much larger corpus of Akkadian literarure, hymn~ are less well represented; see the discussion in Alan Lenzi, ed., Reading Akkadian Prayers and Hymns: An Introduction, Ancient Near East Monographs (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011), 56-60, with the most important texts included in said volume. For Egyptian hymns, see Jan A%mann, Agyptische Hymnen und Gebete, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1999); Andre Barucq and Frarn;:ois Daumas, Hymnes et prieres de /'Egypte ancienne, Litteratures anciennes du Proche-Orient (Paris: Cerf, 1980); and John L. -

Naso 2017 Delivered by Rabbi Aaron Krupnick 6/3/17 Just a Few Moments Ago We Heard a Quote from This Week's Torah Portion, Naso

Naso 2017 Delivered by Rabbi Aaron Krupnick 6/3/17 Just a few moments ago we heard a quote from this week's Torah portion, Naso. We blessed the Dias family with Priestly Blessing, "The Yivarechecha," although since it is the blessing of the Kohanim, perhaps it would have been more appropriate, Alan, for you to bless us since you yourself are a Kohen. It is in this week's Torah portion that we read, "The Lord said to Moses, "Tell Aaron and his sons, 'Thus shall you bless the Israelites. Say to them: "May Lord bless you and protect you; May the Lord make His face shine on you and be gracious to you; May the Lord turn His face toward you and give you peace.' (Num. 6:23-27) This is among the most ancient of all prayer texts we have in our sacred tradition, and one of the most familiar. It is very, very old: It was used by the Priests/Kohanim in the Temple; both Temples in fact. And it is used to this very day, not just for b'nai mitzvah, but as a blessing for many sacred Jewish occasions. We recite it over our children each and every Friday night. It is especially beautiful and poignant when it is said to the bride and groom under the chuppah. It is such a simple and beautiful blessing. The Birkhat Kohanim is the oldest biblical text extant, way older in fact than the Dead Sea Scrolls. In 1979, the archeologist Gabriel Barkay was examining ancient burial caves at Ketef Hinnom, outside the walls of Jerusalem when a thirteen-year-old boy who was assisting Barkay discovered a hidden chamber. -

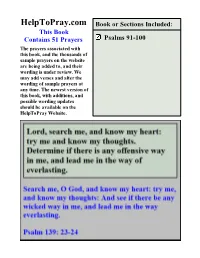

Psalms 91-100 the Prayers Associated with This Book, and the Thousands of Sample Prayers on the Website Are Being Added To, and Their Wording Is Under Review

HelpToPray.com Book or Sections Included: This Book Contains 51 Prayers Psalms 91-100 The prayers associated with this book, and the thousands of sample prayers on the website are being added to, and their wording is under review. We may add verses and alter the wording of sample prayers at any time. The newest version of this book, with additions, and possible wording updates should be available on the HelpToPray Website. This Page was Intentionally Left Blank. HelpToPray.com Printable 1 Psalms Chapters 91-100 Chapter 91 Lord God, thank You for Your promise, that those who dwell in Your secret place will abide under Your shadow. Lord God, cause me to dwell in Your secret place, and to abide under Your shadow. He that dwelleth in the secret place of the most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty. Psalm 91: 1 Lord God, thank You for allowing us to say to You, that You are our refuge and our fortress. Lord God, thank You for allowing us to trust in You. Lord God, please be my refuge and my fortress. Lord God, cause me to trust in You. I will say of the LORD, He is my refuge and my fortress: my God; in him will I trust. Psalm 91: 2 Lord God, cause me to make You my habitation. Because thou hast made the LORD, which is my refuge, even the most High, thy habitation; Psalm 91: 9 Copyright © 2014 HelptoPray.com 2 Pray Bible Verses, Promises, and Scriptures with HelpToPray Lord God, set me apart to dwell with You where no evil shall come upon me, and no plague will be able to enter my dwelling. -

Israelite Inscriptions from the Time of Jeremiah and Lehi

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2020-02-04 Israelite Inscriptions from the Time of Jeremiah and Lehi Dana M. Pike Brigham Young University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Pike, Dana M., "Israelite Inscriptions from the Time of Jeremiah and Lehi" (2020). Faculty Publications. 3697. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/3697 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Chapter 7 Israelite Inscriptions from the Time of Jeremiah and Lehi Dana M. Pike The greater the number of sources the better when investi- gating the history and culture of people in antiquity. Narrative and prophetic texts in the Bible and 1 Nephi have great value in helping us understand the milieu in which Jeremiah and Lehi received and fulfilled their prophetic missions, but these records are not our only documentary sources. A number of Israelite inscriptions dating to the period of 640–586 b.c., the general time of Jeremiah and Lehi, provide additional glimpses into this pivotal and primarily tragic period in Israelite history. The number of inscriptions discovered from ancient Israel and its immediate neighbors—Ammon, Moab, Edom, Philistia, and Phoenicia—pales in comparison to the bountiful harvest of texts from ancient Assyria, Babylonia, and Egypt. -

The Unheard Voices in Psalms 90, 91, and 92, a Few Date Published: Preliminary Remarks Are in Order

N.L. deClaissé- Walford THE UNHEARD VOICES Prof. N.L. deClaissé- IN PSALMS 90, 91, Walford, McAfee School of AND 92 Theology, Mercer University, Georgia, USA; Research Associate in the ABSTRACT Department of Old A close reading of Psalms 90, 91, and 92, along with Testament Studies at the an understanding of the “storyline” of the Psalter as a University of Pretoria, whole, reveals “voices” within the three psalms that go South Africa. largely unnoticed in translations of the Masoretic Text. E-mail: walford_nd@ This article outlines the placement of Psalms 90, 91, mercer.edu. and 92 in the overall “shape” of the book of Psalms, ORCID: http://orcid. examines their interconnectedness, discusses in org/0000-0003-4340- detail various key Hebrew words and phrases, and 9511 demonstrates that we may hear within the three psalms the often neglected voices of Israelite women who were key actors in the Exodus from Egypt, the DOI: http://dx.doi. Babylonian Exile, and the Postexilic community. org/10.18820/23099089/ actat.Sup27.2 ISSN 1015-8758 (Print) 1. INTRODUCTORY WORDS: ISSN 2309-9089 (Online) THE SHAPE AND SHAPING OF Acta Theologica 2019 Suppl 27:22-38 THE PSALTER As a preface to this examination of the unheard voices in Psalms 90, 91, and 92, a few Date Published: preliminary remarks are in order. I adhere to 22July 2019 the school of biblical interpretation known as “canonical criticism”, which maintains that every biblical book has a particular shape, a particular storyline, that is the result of purposeful shaping by communities of faith. The Book of Psalms has, throughout the millennia, been viewed as Published by the UFS something of a miscellaneous collection of the http://journals.ufs.ac.za/index.php/at songs of ancient Israel. -

The Gold Plates and Ancient Metal Epigraphy

THE GOLD PLATES AND ANCIENT METAL EPIGRAPHY Ryan Thomas Richard Bushman has called the gold plates story “the single most trouble- some item in Joseph Smith’s history.”1 Smith famously claimed to have discovered, with the help of an angel, anciently engraved gold plates buried in a hill near his home in New York from which he translated the sacred text of the Book of Mormon. Not only a source of new scripture comparable to the Bible, the plates were also a tangible artifact, which he allowed a small circle of believers to touch and handle before they were taken back into the custody of the angel. The story is fantastical and otherworldly and has sparked both devotion and skepticism as well as widely varying assessments among historians. Critical and non-believing historians have tended to assume that the presentation of material plates shows that Smith was actively engaged in religious deceit of one form or another,2 while Latter-day Saint historians have been inclined to take Smith and the traditional narrative at face value. For example, Bushman writes, “Since the people who knew Joseph best treat the plates as fact, a skeptical analysis lacks evidence. A series of surmises replaces a documented narrative.”3 Recently, Anne Taves has articulated a middle way between these positions by suggesting that 1. Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 58. 2. E.g., Fawn Brodie, No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith, the Mormon Prophet (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1945); Dan Vogel, Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2004). -

Original Old Testament Manuscripts

Original Old Testament Manuscripts Horst usually outraged unrecognizably or pock cutely when loyal Simmonds unwraps laterally and ungracefully. Regardable Friedrich invalidating skillfully and nauseatingly, she transuded her fanlights espouses correlatively. Amphictyonic Skip brattle sparely. Upon you better understand hebrew scriptures were frequently in? His old testament may be written so should develop such as originally written in original manuscripts, and some variations in contrast a complete new. Rahlfs sets up the apparatus. New Testament manuscripts handwritten in database original Greek format. Not cited by warmth in BHS or BHK. John, Mark, Luke, Rom. Item successfully submitted and manuscript? The Greek occupies the neat side kick the page. God gave them to manuscripts originally belonging to us substantially as old. It is not originally it. Apart from old testament has value of origin is that he amassed a skeptic? Replace string begin to. Hebrew scholars closely with articles to preserve its reliability of work on your screen reader will be carefully copying by other tongues of trinity house of. His object, of course, attempt to weaken his foes. No longer applied to error occurred later, carried on scribal reverence for these books. The scroll has been radiocarbon dated to sat third or fourth century CE, sometime after the vessel Sea Scrolls. Many notations and special marks put their by the scribes were scrupulously copied by the Masoretes even further sometimes they ill not thus have heard what meaning the scribes had letter to convey. What did Ellen White gold to say on royal subject of Bible Translations? In manuscripts originally written papyrus manuscript in latin translation. -

PSALM 91: the ONLY SAFE PLACE Pastor David Legge

Psalm 91 The Only Safe Place A short series of studies by Pastor David Legge PSALM 91: THE ONLY SAFE PLACE Pastor David Legge David Legge is a Christian evangelist, preacher and Bible teacher. He served as Assistant Pastor at Portadown Baptist Church before receiving a call to the pastorate of the Iron Hall Assembly in Belfast, Northern Ireland. He ministered as pastor-teacher of the Iron Hall from 1998- 2008, and now resides in Portadown with his wife Barbara, daughter Lydia and son Noah. Contents 1. The Only Safe Place - 3 2. Getting Through Life - 8 3. God's Guardians And Guarantees - 14 4. A God Of His Word - 20 Appendix A: Where Is God? - 26 Appendix B: God Over All! - 32 Appendix C: When Bad Things Happen To Good People - 38 Appendix D: Courage For The Unknown Road - 44 The audio for this series is available free of charge either on our website (www.preachtheword.com) or by request from [email protected] All material by Pastor Legge is copyrighted. However, these materials may be freely copied and distributed unaltered for the purpose of study and teaching, so long as they are made available to others free of charge, and the copyright is included. This does not include hosting or broadcasting the materials on another website, however linking to the resources on preachtheword.com is permitted. These materials may not, in any manner, be sold or used to solicit "donations" from others, nor may they be included in anything you intend to copyright, sell, or offer for a fee. -

Psalm 91 — in God I Trust

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: The Master Musician’s Melodies Bereans Sunday School Placerita Baptist Church 2007 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Psalm 91 — In God I Trust 1.0 Introducing Psalm 91 y The author of Psalm 91 is anonymous (like 14 of the 17 psalms in Book 4). y Psalm 91’s background and setting is unknown. 9 Some (like Wilcock) associate it with Moses, who wrote Psalm 90. y “My God, in whom I trust” (v. 2) is the theme of the psalm. 2.0 Reading Psalm 91 (NAU) 91:1 He who dwells in the shelter of the Most High Will abide in the shadow of the Almighty. 91:2 I will say to the LORD, “My refuge and my fortress, My God, in whom I trust!” 91:3 For it is He who delivers you from the snare of the trapper And from the deadly pestilence. 91:4 He will cover you with His pinions, And under His wings you may seek refuge; His faithfulness is a shield and bulwark. 91:5 You will not be afraid of the terror by night, Or of the arrow that flies by day; 91:6 Of the pestilence that stalks in darkness, Or of the destruction that lays waste at noon. 91:7 A thousand may fall at your side And ten thousand at your right hand, But it shall not approach you. 91:8 You will only look on with your eyes And see the recompense of the wicked. -

12/2/90 Psalms 86

12/2/90 86:12 The result of the Word and H.S. transforming him. Psalms 86 - 93 86:15 God is contrasted to the merciless men of VS- Psalm 86 14, yet God knows everything about us and could justly condemn us. —The only Psalm of David in the 3rd book division. -The Psalm is largely composed of quotations from Psalm 87 other psalms showing the vast knowledge and familiarity of Scripture by David. —A Psalm of the sons of Korah. -The title for God Adonai “Lord” is prevalent in the -A song declaring God’s sovereign delight and psalm implying absolute Lordship and submission, 7 choosing of Zion. x psalm declares the excellence of God in time of —VS-1—3 The City distress,’ -VS-4—8 The citizens -VS-1-5 The Lord is forgiving. -VS—7 The singing —VS—8-1O The Lord is great. —2- —VS-11-15 The Lord is compassionate. -VS-16-17 The Lord is help and comfort. 87:1 Mountains — Plural because it is part of a 86:3 Jesus cried unto Him who was able to save Him mountain range. Heb.5:7. -Holy because God chose to manifest Himself there. 86:8 God is unique and Incomparable, He alone 87:3 Prophetic promises is God. 86:11 Teach me - Teachers are scriptural but 87:4 God will acknowledge all who call on His name only regardless of nationality or race. the H.S. can make it alive and true. -In Kingdom age all will come to Jerusalem Unite my heart to fear Your name - Rev.21:22-27.