Dndia Frogeot 1, 2 Febary 1955

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

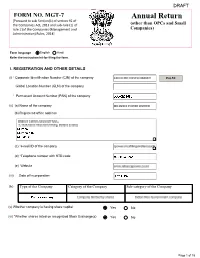

Annual Return

DRAFT FORM NO. MGT-7 Annual Return [Pursuant to sub-Section(1) of section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and sub-rule (1) of (other than OPCs and Small rule 11of the Companies (Management and Companies) Administration) Rules, 2014] Form language English Hindi Refer the instruction kit for filing the form. I. REGISTRATION AND OTHER DETAILS (i) * Corporate Identification Number (CIN) of the company Pre-fill Global Location Number (GLN) of the company * Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the company (ii) (a) Name of the company (b) Registered office address (c) *e-mail ID of the company (d) *Telephone number with STD code (e) Website (iii) Date of Incorporation (iv) Type of the Company Category of the Company Sub-category of the Company (v) Whether company is having share capital Yes No (vi) *Whether shares listed on recognized Stock Exchange(s) Yes No Page 1 of 15 (a) Details of stock exchanges where shares are listed S. No. Stock Exchange Name Code 1 2 (b) CIN of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Pre-fill Name of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Registered office address of the Registrar and Transfer Agents (vii) *Financial year From date 01/04/2020 (DD/MM/YYYY) To date 31/03/2021 (DD/MM/YYYY) (viii) *Whether Annual general meeting (AGM) held Yes No (a) If yes, date of AGM (b) Due date of AGM 22/09/2021 (c) Whether any extension for AGM granted Yes No II. PRINCIPAL BUSINESS ACTIVITIES OF THE COMPANY *Number of business activities 1 S.No Main Description of Main Activity group Business Description of Business Activity % of turnover Activity Activity of the group code Code company D D1 III. -

A Tradition of Engineering Excellence a Tradition of Engineering Excellence

th ANNUAL REPORT 10 6th 10 6 ANNUAL2013-201 REPORT4 2013-2014 A Tradition of Engineering Excellence A Tradition of Engineering Excellence WALCHANDNAGAR INDUSTRIES LIMITED WALCHANDNAGAR INDUSTRIES LIMITED PDF processed with CutePDF evaluation edition www.CutePDF.com Seth Walchand Hirachand’s life was truly a triumph of persistence over adversity. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Board of Directors Chakor L. Doshi Chairman Dilip J. Thakkar Dr. Anil Kakodkar G. N. Bajpai Director Director Director A. R. Gandhi Bhavna Doshi Director Director G. K.Pillai Chirag C. Doshi Managing Director & CEO Managing Director Corporate Information Registered Office Walchandnagar Industries Ltd. 3, Walchand Terraces, Tardeo Road, Mumbai - 400 034 Tel. No. (022) 4028 7104 / 4028 7110 / 2369 2295 Pune Office Walchand House 167A, 2/8+2/9, Karve Road, Kothrud, Pune - 411 038 Tel. No. (020) 3025 2600 Factories Walchandnagar, Dist. Pune, Maharashtra Satara Road, Dist. Satara, Maharashtra Attikola, Dharwad, Karnataka. Compliance Officer Mr. G. S. Agrawal Vice President (Legal & Taxation) and Company Secretary Contents Registrar & Share Transfer Agents 3 Letter from the Chairman Link Intime India Pvt. Ltd. C-13, Pannalal Silk Mills Compound, L.B.S. Marg, Bhandup (W), 4 Notice to the Shareholders Mumbai - 400 078. Tel. No. (022) 2594 6970-80 18 Directors’ Report Fax No. (022) 2594 6969 E-mail: [email protected] 21 Management Discussion and Analysis Auditors 24 Report on Corporate Governance K.S. Aiyar & Co. Chartered Accountants 36 Auditors’ Report Principal Bankers 40 Financials State Bank of India Bank of India ING Vysya Bank Ltd. Letter from the Chairman Dear Members, It is my pleasure to welcome you all to this 106th Annual General Meeting and present the Annual Report of your Company. -

Institute Information Admission Brochure 2020-21

Walchand College of Engineering Sangli (Government Aided Autonomous Institute) Information Brochure (Draft Guideline document) (Based on previous data) for Entry Level Admissions of F.Y. B.Tech, F.Y. M.Tech & DSE 2020-21 For any further information please email to: [email protected] Information Prepared by Mr. K.V.Madhale and Mr.A.A.Powar ADMISSION PROCEDURE Admissions to WCE, Sangli are strictly based on merit only through on-line centralised admission process (CAP) as per the guidelines of Government of Maharashtra and are conducted “The Competent Authority, the Commissioner of State Common Entrance Test Cell, Maharashtra State” (UG, PG programs). Undergraduate (Degree) Admissions Undergraduate (B. Tech.) admissions: Admissions to WCE, Sangli are strictly based on merit only through on-line centralised admission process (CAP) as per the guidelines of Government of Maharashtra and are conducted “The Competent Authority, the Commissioner of State Common Entrance Test Cell, Maharashtra State”. Eligibility and Entrance Test: Please refer website https://www.mahacet.org. , https://mhtcet2020.mahaonline.gov.in/ List of document required for admission: Please refer Link: https://mhtcet2020.mahaonline.gov.in/Content/PDF/News/Documents_Required_for_Admissi ons_to_Engineering_Pharmacy_Agriculture_Fisheries_and_Dairy_Technology_Courses.pdf Admission Process: Please refer to website https://www.mahacet.org and http://www.dtemaharashtra.gov.in/index.html. F.Y. B.Tech Admission (CAP) Related old Links 2019-20 Admission Link: https://fe2019.mahacet.org/staticpages/homepage.aspx -

Application Form for Admission at Walchand College of Engineering, Sangli for the Academic Year 2020 – 2021

Dear Sir / Madam, Reg. : Admission at Walchand College of Engineering, Sangli. As requested by you, we are forwarding herewith Personal Data Form along with Application Form for Admission at Walchand College of Engineering, Sangli for the Academic Year 2020 – 2021. While submitting the Personal Data Form & Application Form, please submit the Attested Copies of the following Certificates: 1. Certificate of Marks (Mark List) obtained at the qualifying examination H.S.C. (Std. XII). 2. School Leaving Certificate, after qualifying examination passed. 3. Certificate of Marks (Mark List) obtained at S.S.C. (Std. X) or its equivalent examination. 4. If S.S.C. / H.S.C. passed outside Maharashtra, Maharashtra Domicile Certificate in respect of his / her father. 5. Copy of MHT - CET – 2020 / JEE – 2020 Result. 6. Fill up CAP Form and submit us the acknowledgement copy issued by CAP Authority. Please return the (Hard Copy) Application Form, Personal Data Form duly filed alongwith the certificates as mentioned below to: Mr. Umesh M. Masurkar Hindustan Construction Co. Ltd., Hincon House, LB Shastri Marg, Vikhroli (W), Mumbai – 400 083. Tel.No.: 2575 5248 For SETH WALCHAND HIRACHAND MEMORIAL TRUST Authorised Signatory APPLICATION FOR NOMINATION FOR ADMISSION TO FIRST YEAR OF THE FOUR YEAR ENGINEERING DEGREE COURSE IN THE WALCHAND COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, SANGLI. SETH WALCHAND HIRACHAND MEMORIAL TRUST HINCON HOUSE, LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI MARG, VIKHROLI ( WEST ), MUMBAI 400 083. PERSONAL DATA ( TO BE FILLED BY EMPLOYEE ) Full Name (Block Letters) : ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

WALCHAND INSTITUTE of TECHNOLOGY Seth Walchand Hirachand Marg, Ashok Chowk, Post Box No.634, SOLAPUR – 413006

Shri Aillak Pannalal Digamber Jain Pathashala’s WALCHAND INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Seth Walchand Hirachand Marg, Ashok Chowk, Post Box No.634, SOLAPUR – 413006. Accredited by NAAC A+ Grade Accredited by NBA, New Delhi for Civil Engineering., Mechanical Engineering., Electronics Engineering. , Electronics & Telecommunication Engineering. Winner of AICTE-CII Survey 2013 , 2014 & 2018 Award for Best Industry–Linked Institute. Recognized by AICTE, New Delhi and permanently affiliated to Solapur University, Solapur : 2651388, 2652700 Fax : (0217) 2651538 Email: [email protected] Website : www.witsolapur.org Estimate of Fees Academic fees for the students admitted in First Year Engineering 2019-2020 only. FE SE TE BE Particulars 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 2022-23 Tuition Fee 92919 92919 92919 92919 Development Fee 12081 12081 12081 12081 Other Fee (Univ. Fee) 507 507 507 507 Lib. & Lab Caution Deposit 1000 - - - Total Fees 106507 105507 105507 105507 The above fees are for General Category students only and for Reserve Category students fees will be informed by college after verification of necessary documents and eligibility. Students are required to pay fees yearly. Note: * Please note that, as per provisions of the Maharashtra Unaided Private Professional Educational Institutions (Regulation of Admission and Fees) Act, 2015 any upward revision of fees shall be binding and mandatory for payment on demand from the college authorities as approved by the Fee Regulating Authority, Mumbai from time to time. Mode of Payment: NEFT/RTGS/D.D. Bank A/c Details for online payment / NEFT/ RTGS:- Bank Account Name : Principal, Walchand Institute of Technology, Solapur. Bank Name : State Bank of India Address of the Bank : Balives Branch, Solapur Current Account Number : 36923196293 IFSC Code : SBIN0000483 MICR Code : 413002002 While making NEFT/RTGS payment please mention student name in remark column. -

Annual Report 2019-20

Annual Report 2019-20 Contents Chairman’s Letter .................................... 4 Company Information ............................. 11 Management Discussion & Analysis ...... 12 Corporate Governance ............................ 21 Board’s Report ........................................ 41 Business Responsibility Report .............. 70 Standalone Auditors’ Report ................... 76 Standalone Financial Statements ............ 90 Consolidated Auditors’ Report ............... 163 Consolidated Financial Statements ........ 176 Notice ...................................................... 288 Highlights 2019-20 • Turnover: `3643.64 crore in FY20 vs. `4603.49 crore in FY19 • EBITDA margin (excluding Other Income) was 12.7% in FY20 vs. 12.8% in FY19 • Net Loss of `168.7 crore compared to Loss of `1925.6 crore in FY19 • Infusions of liquidity in FY20: `348 crore arbitration award collections • Senior lenders approved carve out ~`2,800 crore of Debt along with pool of Awards/Claims, to address Company’s asset-liability mismatch • Supreme Court struck down Section 87 of Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 1996, on Nov 27, 2019, freeing HCC to execute awards of `1,584 crore • CCEA amendment circular dt. Nov 20, 2019 to help accelerate realization of arbitral awards; Govt. agencies to take the opinion of Law Officer before challenging arbitral awards and requiring a refund of BGs given for interest component (~`850 crore in HCC’s case) • Conciliations of Awards/Claims of ~Rs.5,000 crore underway with NHAI • Robust free cash flow -

Mumbai-400 051 Dear

July 13, 201 8 National Stock Exchange of lndia Ltd, Exchange Plaza,Bandra-Kurla Complex, Bandra (East),Mumbai-400 051 Dear Sir, Sub: Disclosure of Outcome of the 92ndAnnual General Meeting (AGM) of the Company held on July 12, 2018 as per Regulation 30 of the SEBI {Listins Obliqations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 (hereinafter 'SEBI Listing Regulations'I At the 92"d Annual General Meeting of the Company held on July 12, 2018 at Walchand Hirachand Hall, Indian Merchants' Chamber, Indian Merchants' Chamber Marg, Churchgate, Mumbai-400 020, all the 10 items of business contained in the Notice of the AGM as below were approved by the shareholders with requisite majority. Resolution No. 1 : Ordinary Resolution for adoption of Audited Standalone & Consolidated Financial Statements of the Company for the year ended March 31, 2018 and the Report of the Board of Directors and Auditors thereon. Resolution No. 2 Special Resolution for re-appointment of Mr. N. R. Acharyulu (DIN: 02010249) as a Non Executive - Non lndependent Director. liable to retire by rotation. Resolution No. 3 : Special Resolution for continuance of Directorship of Mr. Sharad M. Kulkarni (DIN: 00003640), lndependent Director of the Company. Resolution No. 4: Special Resolution for re-appointment of Mr. Ajit Gulabchand (DIN: 00010827) as Chairman & Managing Director of the Company for a period of five years effective from April 1, 201 8 (including terms of remuneration for FY 201 8-1 9) Resolution No. 5 : Ordinary Resolution for payment of Remuneration to Ms. Shalaka Gulabchand Dhawan, Whole-time Director for the period 3othApril, 2018 to 2gthApril, 2019. -

WALCHAND INSTITUTE of TECHNOLOGY Mandatory Disclosure

WALCHAND INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SOLAPUR Mandatory Disclosure Mandatory Disclosure 1) Name of the Institution : WALCHAND INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, SOLAPUR Address of the Institution : Seth Walchand Hirachand Marg, Post Box No. 634, Ashok Chowk City & Pin Code : SOLAPUR – 413 006 State / UT : Maharashtra Longitude & Latitude : Longitude : 75.9166 Latitude : 17.6833 Phone No. with STD Code : 0217 – 2651388, 2652700, 2653040 FAX number with STD Code : 0217 – 2651538 E-mail : [email protected] [email protected] Website : www.witsolapur.org 2) Name and Address of the Trust : Shri Aillak Pannalal Digambar Jain Pathashala , Solapur. : Seth Walchand Hirachand Marg, Post Box No.634, Ashok Chowk, Solapur – 413 006 3) Name and Address of the Principal : Name of the Principal : Dr. S. A. Halkude : Seth Walchand Hirachand Marg, Post Box No. 634 , Ashok Chowk, Solapur – 413 006 Phone Number with STD Cod : 0217 – 2651538 (O), 2341856 (R), 09422457776 (M) FAX number with STD Code : 0217 – 2651538 E-mail : [email protected], [email protected] Highest Degree : Ph.D. (Civil Engg.) Field of Specialization : Civil Engg. - Geotechnical Engg. 4)Name of the affiliatingUniversity : Punyashlok Ahilyadevi Holkar Solapur University, Solapur Address : Solapur-Pune National Highway, Kegaon, Solapur – 413 255 Website : su.digitaluniversity.ac 5) Governance : ● Governing Body 5.1.1 Composition of the Governing Body (Board of Governance) Sr. No. Designation Name and Address Shri. Arvind R. Doshi Chairman : 1 Chairman, 2A, Widncliff, 50-D Peddar Road, Chairman, 2A, (Eminent Industrialist) Widncliff, 50-D Peddar Road, Cumballa Hill, Mumbai – 400026 Member : Shri. Bhushan Vilas Shah 2 (Eminent Industrialist) Engineer, 94, Siddheshwar Peth, Solapur – 413 001 Member : Dr. -

BCAS New.Indd

For Members only. For Private Circulation only. Price: R10 BCASHarnessing Talent and Providing Quality Service ANewsletter Monthly Newsletter of the Bombay Chartered Accountants’ Society Vol. 17 No. 09 December 2014 Vice-President’s Communiqué Dear Member, LECTURE MEETINGS Greetings! Speaker : Milind S. Kothari, Chartered Accountant As I write this, the morning is much cooler and the rays of the sun Subject : Global Services Transformation - Are Indian CA firms on a winter morning appear more golden. There is a certain calm insulated? that envelopes the city during cooler days. However, the daytime Venue : Walchand Hirachand Hall, 4th Floor, IMC, Churchgate, is still hot and the work in a CA’s life continues unabated, with Mumbai 400 020 assessments in full swing. Day, Date & Time : Wednesday, 21st January, 2015, 6.15 p.m.** In America, the last Thursday of November is celebrated as the Thanksgiving Day. This day is dedicated to offer thanks for the Speaker : Hiro Rai, Advocate blessing of the harvest and of the preceding year. I particularly Subject : Important Income-tax decisions of 2014 like the idea of offering thanks and especially taking time to Venue : Walchand Hirachand Hall, 4th Floor, IMC, Churchgate, remember all the blessings we have in our life–as people, things, Mumbai 400 020 and events. Even if our life seems challenging, somewhat uphill Day, Date & Time : Thursday, 29th January, 2015, 6.15 p.m.** all the way, there is bound to be some amount of ‘blessing’ we can cull out and be grateful for. Gratitude is such an essential Speaker : Satya Poddar, Ph. D. -

Hirachand Nemchand College of Commerce Solapur Rar 2008-09

HIRACHAND NEMCHAND COLLEGE OF COMMERCE SOLAPUR RAR 2008-09 Part I: Institutional Data A) Profile of the College 1. Name and address of the college: Name: Hirachand Nemchand College of Commerce, Solapur Address: Walchand Hirachand Marg, Ashok Chowk, Solapur City: Solapur District: Solapur State: Maharashtra Pin code: 413006 Website: www.hnccsolapur.org 2. For communication: Office Name Area/ STD code Tel. No. Fax No. E-mail Principal 0217 2651600 2656121 [email protected] Dr V. B. Kakade Vice Principal ……….. -- -- -- -- Steering Committee 0217 2728188 2621608 [email protected] Coordinator CA. Shrenik H. Shah….. Residence Name Area/ STD Tel. No. Mobile No. code Principal 0217 - 9422423941 Dr V. B. Kakade……………………… Vice Principal ………………………... -- -- -- Steering Committee Coordinator 0217 2328188 9822328188 CA Shrenik H. Shah …….. 1 HIRACHAND NEMCHAND COLLEGE OF COMMERCE SOLAPUR RAR 2008-09 3. Type of Institution: a. By management i. Affiliated College ii. Constituent College b. By funding i. Government ii. Grant-in-aid iii. Self-financed iv. Any other (Specify the type) c. By Gender i. For Men ii. For Women iii. Co-education 4. Is it a recognized minority institution? Yes No If yes, specify the minority status: Religious (Provide the necessary supporting documents) Encl No.01 5. a) Date of establishment of the college: Date Month Year 1st June 1972 b) University to which the college is affiliated (If it is an affiliated college) Solapur University, Solapur Or which governs the college (If it is a constituent college) Universitr UUniv.UUUUUnivers it UuUnivUniversity UUUUUUUniversity So 2 HIRACHAND NEMCHAND COLLEGE OF COMMERCE SOLAPUR RAR 2008-09 6. Date of UGC recognition: Under Section Date, Month & Year Remarks (dd-mm-yyyy) (If any) i. -

Responsible Infrastructure

Sustainability Report 2018-19 Responsible Infrastructure 1 II Table of Contents 1. About the Report 01 2. Message from the Chairman & 02 3. Organisational Overview 03 4. Our Approach to Sustainability 08 5. Engineering Highlights 11 6. Our Employees 13 7. Health and Safety 19 8. Economic Performance 23 9. Environmental Performance 25 10. CoP: UN CEO Water Mandate 29 11. Community Sustainability 32 12. Our Sustainability Performance 34 13. Independent Assurance Statement 36 14. GRI Content Index 38 1 About the Report Responsible Infrastructure 2018-19 is the 10th Annual Sustainability Report of Hindustan Construction Company Ltd. This report has been prepared in accordance with the GRI Standards: Core Option. The report presents management disclosure and performance highlights on the key sustainability issues material to the company. The reporting period is the financial year ending on March 31, 2019. GRI Services reviewed that the GRI content index is clearly presented and the references for all disclosures included align with the appropriate sections in the body of the report. This report includes the 11th The report has undergone limited assurance (as per AA 1000 AS standard) by Thinkthrough Consulting Pvt. Ltd. (TTC), an independent professional services firm. Our reporting boundary is inclusive of all HCC projects in progress during the reporting year. Any exceptions in the boundary with respect to specific performance disclosures are clearly mentioned within the report. We will strive to continue enhancing our sustainability disclosures going ahead. Any feedback and queries are welcome, and may be directed to: Aditya Patwardhan Assistant General Manager Corporate Social Responsibility [email protected] 102-1, 102-2, 102-4, 102-46, 102-50, 102-52, 102-53, 102-54 2 Message from the Chairman & Managing Director Dear Reader, few companies in the country to achieve the landmark of 10 years of consistent reporting. -

Gandhi: Patron Saint of the Lndustrialist Leah Renold for Over a Quarter of a Century Mohandas K

Gandhi: Patron Saint of the lndustrialist Leah Renold For over a quarter of a century Mohandas K. Gandhi maintained a close friendship with G. D. Birla., a wealthy industrialist, who was Gandhi's chief patron. This article explores their relationship which reveals some of the less well known aspects of Gandhi. Despite popular perceptions of Gandhi, he was neither a social nor economic revolutionary. uring the years of the Indian independence movement, a leading Indian industrialist, G. D. Birla, was Mahatma an hi's most generous financia! supporter. While Birla has been described as a devotee of Gandhi, the relationship between the two men was more one of collaboration than of one-sided devotion. Gandhi's campaigns were made possible by drawing from Birla's vast financia! resources while Birla benefited not only from the social and religious prestige which his association with Gandhi brought him, but his economic role and position as a wealthy capitalist was strengthened and glorified. Gandhi gave his blessing to the abundant wealth of Birla with his teaching on trusteeship, a concept which asserted the right of the rich to accumulate and maintain wealth, as long as the wealth was used to benefit society. Gandhi apparently borrowed the concept of trusteeship from the writings of the American millionaire, Andrew Camegie, who had used trusteeship to promote capitalism over socialism. The close relationship between Gandhi and G. D. Birla did not escape scrutiny. B. R. Ambedkar, a leader of the untouchable castes, accused Gandhi of pretending to support the cause of the oppressed while actually supporting the forces of social conservatism.1 Lord Linlithgow, the Viceroy of India, questioned the Gandhi-Birla connection.