Colonialism and Technology Choices in India: a Historical Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk, Information and Capital Flows: the Industrial Divide Between

Discrimination or Social Networks? Industrial Investment in Colonial India Bishnupriya Gupta No 1019 WARWICK ECONOMIC RESEARCH PAPERS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS Discrimination or Social Networks? Industrial Investment in Colonial India Bishnupriya Gupta1 May 2013 Abstract Industrial investment in Colonial India was segregated by the export oriented industries, such as tea and jute that relied on British firms and the import substituting cotton textile industry that was dominated by Indian firms. The literature emphasizes discrimination against Indian capital. Instead informational factors played an important role. British entrepreneurs knew the export markets and the Indian entrepreneurs were familiar with the local markets. The divergent flows of entrepreneurship can be explained by the comparative advantage enjoyed by social groups in information and the role of social networks in determining entry and creating separate spheres of industrial investment. 1 My debt is to V. Bhaskar for many discussions to formalize the arguments in the paper. I thank, Wiji Arulampalam, Sacsha Becker Nick Crafts and the anonymous referees for helpful suggestions and the participants at All UC Economic History Meeting at Caltech, ESTER Research Design Course at Evora and Economic History Workshop at Warwick for comments. I am grateful to the Economic and Social Research Council, UK, for support under research grant R000239492. The errors are mine alone. 1 Introduction Bombay and Calcutta, two metropolitan port cities, experienced very different patterns of industrial investment in colonial India. One was the hub of Indian mercantile activity and the other the seat of British business. The industries that relied on the export market attracted investment from British business groups in the city of Calcutta. -

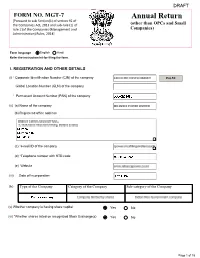

Annual Return

DRAFT FORM NO. MGT-7 Annual Return [Pursuant to sub-Section(1) of section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and sub-rule (1) of (other than OPCs and Small rule 11of the Companies (Management and Companies) Administration) Rules, 2014] Form language English Hindi Refer the instruction kit for filing the form. I. REGISTRATION AND OTHER DETAILS (i) * Corporate Identification Number (CIN) of the company Pre-fill Global Location Number (GLN) of the company * Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the company (ii) (a) Name of the company (b) Registered office address (c) *e-mail ID of the company (d) *Telephone number with STD code (e) Website (iii) Date of Incorporation (iv) Type of the Company Category of the Company Sub-category of the Company (v) Whether company is having share capital Yes No (vi) *Whether shares listed on recognized Stock Exchange(s) Yes No Page 1 of 15 (a) Details of stock exchanges where shares are listed S. No. Stock Exchange Name Code 1 2 (b) CIN of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Pre-fill Name of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Registered office address of the Registrar and Transfer Agents (vii) *Financial year From date 01/04/2020 (DD/MM/YYYY) To date 31/03/2021 (DD/MM/YYYY) (viii) *Whether Annual general meeting (AGM) held Yes No (a) If yes, date of AGM (b) Due date of AGM 22/09/2021 (c) Whether any extension for AGM granted Yes No II. PRINCIPAL BUSINESS ACTIVITIES OF THE COMPANY *Number of business activities 1 S.No Main Description of Main Activity group Business Description of Business Activity % of turnover Activity Activity of the group code Code company D D1 III. -

Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview Debobrat Doley Research Scholar, Dept of History Dibrugarh University Abstract: The British era is a part of the subcontinent’s long history and their influence is and will be seen on many societal, cultural and structural aspects. India as a nation has always been warmly and enthusiastically acceptable of other cultures and ideas and this is also another reason why many changes and features during the colonial rule have not been discarded or shunned away on the pretense of false pride or nationalism. As with the Mughals, under European colonial rule, architecture became an emblem of power, designed to endorse the occupying power. Numerous European countries invaded India and created architectural styles reflective of their ancestral and adopted homes. The European colonizers created architecture that symbolized their mission of conquest, dedicated to the state or religion. The British, French, Dutch and the Portuguese were the main European powers that colonized parts of India.So the paper therefore aims to highlight the growth and development Colonial Indian Architecture with historical perspective. Keywords: Architecture, British, Colony, European, Modernism, India etc. INTRODUCTION: India has a long history of being ruled by different empires, however, the British rule stands out for more than one reason. The British governed over the subcontinent for more than three hundred years. Their rule eventually ended with the Indian Independence in 1947, but the impact that the British Raj left over the country is in many ways still hard to shake off. -

In Late Colonial India: 1942-1944

Rohit De ([email protected]) LEGS Seminar, March 2009 Draft. Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without permission. EMASCULATING THE EXECUTIVE: THE FEDERAL COURT AND CIVIL LIBERTIES IN LATE COLONIAL INDIA: 1942-1944 Rohit De1 On the 7th of September, 1944 the Chief Secretary of Bengal wrote an agitated letter to Leo Amery, the Secretary of State for India, complaining that recent decisions of the Federal Court were bringing the governance of the province to a standstill. “In war condition, such emasculation of the executive is intolerable”, he thundered2. It is the nature and the reasons for this “emasculation” that the paper hopes to uncover. This paper focuses on a series of confrontations between the colonial state and the colonial judiciary during the years 1942 to 1944 when the newly established Federal Court struck down a number of emergency wartime legislations. The courts decisions were unexpected and took both the colonial officials and the Indian public by surprise, particularly because the courts in Britain had upheld the legality of identical legislation during the same period. I hope use this episode to revisit the discussion on the rule of law in colonial India as well as literature on judicial behavior. Despite the prominence of this confrontation in the public consciousness of the 1940’s, its role has been downplayed in both historical and legal accounts. As I hope to show this is a result of a disciplinary divide in the historical engagement with law and legal institutions. Legal scholarship has defined the field of legal history as largely an account of constitutional and administrative developments paralleling political developments3. -

A Tradition of Engineering Excellence a Tradition of Engineering Excellence

th ANNUAL REPORT 10 6th 10 6 ANNUAL2013-201 REPORT4 2013-2014 A Tradition of Engineering Excellence A Tradition of Engineering Excellence WALCHANDNAGAR INDUSTRIES LIMITED WALCHANDNAGAR INDUSTRIES LIMITED PDF processed with CutePDF evaluation edition www.CutePDF.com Seth Walchand Hirachand’s life was truly a triumph of persistence over adversity. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Board of Directors Chakor L. Doshi Chairman Dilip J. Thakkar Dr. Anil Kakodkar G. N. Bajpai Director Director Director A. R. Gandhi Bhavna Doshi Director Director G. K.Pillai Chirag C. Doshi Managing Director & CEO Managing Director Corporate Information Registered Office Walchandnagar Industries Ltd. 3, Walchand Terraces, Tardeo Road, Mumbai - 400 034 Tel. No. (022) 4028 7104 / 4028 7110 / 2369 2295 Pune Office Walchand House 167A, 2/8+2/9, Karve Road, Kothrud, Pune - 411 038 Tel. No. (020) 3025 2600 Factories Walchandnagar, Dist. Pune, Maharashtra Satara Road, Dist. Satara, Maharashtra Attikola, Dharwad, Karnataka. Compliance Officer Mr. G. S. Agrawal Vice President (Legal & Taxation) and Company Secretary Contents Registrar & Share Transfer Agents 3 Letter from the Chairman Link Intime India Pvt. Ltd. C-13, Pannalal Silk Mills Compound, L.B.S. Marg, Bhandup (W), 4 Notice to the Shareholders Mumbai - 400 078. Tel. No. (022) 2594 6970-80 18 Directors’ Report Fax No. (022) 2594 6969 E-mail: [email protected] 21 Management Discussion and Analysis Auditors 24 Report on Corporate Governance K.S. Aiyar & Co. Chartered Accountants 36 Auditors’ Report Principal Bankers 40 Financials State Bank of India Bank of India ING Vysya Bank Ltd. Letter from the Chairman Dear Members, It is my pleasure to welcome you all to this 106th Annual General Meeting and present the Annual Report of your Company. -

Myth, Language, Empire: the East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-10-2011 12:00 AM Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 Nida Sajid University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Nida Sajid 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Cultural History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Sajid, Nida, "Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 153. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/153 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 (Spine Title: Myth, Language, Empire) (Thesis format: Monograph) by Nida Sajid Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Nida Sajid 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners _____________________ _ ____________________________ Dr. -

On India's Postcolonial Engagement with the Rule

ON INDIA’S POSTCOLONIAL ENGAGEMENT WITH THE RULE OF LAW Moiz Tundawala* By rescuing the rule of law from ideological abuse, this paper explores in its postcolonial career in India, continuities with and distinctiveness from the colonial experience. Specifically focusing on the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court on civil liberties, equality and social rights, it claims that ideas of the exceptional and of the outsider have been integral to the mod- ern rule of law project, and that marked continuities can be noticed with the colonial past in so far as they have been acknowledged in Indian public law practice. India’s distinctiveness, though, lies in the invocation of exceptions for the sake of promoting popular welfare in a postcolonial democracy. I. INTRODUCTION As soon as India acquired independence in 1947, it was con- fronted with the most difficult challenges pertaining to its organization into a national community and state. Those who had once been at the forefront of its freedom struggle were now tasked with the exciting but daunting responsibility of institutionalizing governmental arrangements which would best facilitate its fresh tryst with destiny. What options were available to the founding framers as they began deliberating over possible constitutional principles for India’s political organization? It was clear that something new was on the horizons; the British were leaving, and the thought of them being replaced by the descendant of the last Mughal ruler did not even occur to anyone. But then, was it possible to ignore history altogether and completely start afresh? India, conceptualized in whichever way, was by no means a tab- ula rasa. -

The Keys to British Success in South Asia COLIN WATTERSON

The Keys to British Success in South Asia COLIN WATTERSON “God is on everyone’s side…and in the last analysis he is on the side with plenty of money and large armies” -Jean Anouilh For a period of a period of over one hundred years, the British directly controlled the subcontinent of India. How did a small island nation come on the Edge of the North Atlantic come to dominate a much larger landmass and population located almost 4000 miles away? Historian Sir John Robert Seeley wrote that the British Empire was acquired in “a fit of absence of mind” to show that the Empire was acquired gradually, piece-by-piece. This will paper will try to examine some of the most important reasons which allowed the British to successfully acquire and hold each “piece” of India. This paper will examine the conditions that were present in India before the British arrived—a crumbling central political power, fierce competition from European rivals, and Mughal neglect towards certain portions of Indian society—were important factors in British control. Economic superiority was an also important control used by the British—this paper will emphasize the way trade agreements made between the British and Indians worked to favor the British. Military force was also an important factor but this paper will show that overwhelming British force was not the reason the British military was successful—Britain’s powerful navy, ability to play Indian factions against one another, and its use of native soldiers were keys to military success. Political Agendas and Indian Historical Approaches The historiography of India has gone through four major phases—three of which have been driven by the prevailing world politics of the time. -

MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 to the Present)

MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 to the Present) STUDY MATERIAL I / II SEMESTER HIS1(2)C01 Complementary Course of BA English/Economics/Politics/Sociology (CBCSS - 2019 ADMISSION) UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION Calicut University P.O, Malappuram, Kerala, India 673 635. 19302 School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION STUDY MATERIAL I / II SEMESTER HIS1(2)C01 : MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 TO THE PRESENT) COMPLEMENTARY COURSE FOR BA ENGLISH/ECONOMICS/POLITICS/SOCIOLOGY Prepared by : Module I & II : Haripriya.M Assistanrt professor of History NSS College, Manjeri. Malappuram. Scrutinised by : Sunil kumar.G Assistanrt professor of History NSS College, Manjeri. Malappuram. Module III&IV : Dr. Ancy .M.A Assistant professor of History School of Distance Education University of Calicut Scrutinised by : Asharaf koyilothan kandiyil Chairman, Board of Studies, History (UG) Govt. College, Mokeri. Modern Indian History (1857 to the present) Page 2 School of Distance Education CONTENTS Module I 4 Module II 35 Module III 45 Module IV 49 Modern Indian History (1857 to the present) Page 3 School of Distance Education MODULE I INDIA AS APOLITICAL ENTITY Battle Of Plassey: Consolodation Of Power By The British. The British conquest of India commenced with the conquest of Bengal which was consummated after fighting two battles against the Nawabs of Bengal, viz the battle of Plassey and the battle of Buxar. At that time, the kingdom of Bengal included the provinces of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. Wars and intrigues made the British masters over Bengal. The first conflict of English with Nawab of Bengal resulted in the battle of Plassey. -

Institute Information Admission Brochure 2020-21

Walchand College of Engineering Sangli (Government Aided Autonomous Institute) Information Brochure (Draft Guideline document) (Based on previous data) for Entry Level Admissions of F.Y. B.Tech, F.Y. M.Tech & DSE 2020-21 For any further information please email to: [email protected] Information Prepared by Mr. K.V.Madhale and Mr.A.A.Powar ADMISSION PROCEDURE Admissions to WCE, Sangli are strictly based on merit only through on-line centralised admission process (CAP) as per the guidelines of Government of Maharashtra and are conducted “The Competent Authority, the Commissioner of State Common Entrance Test Cell, Maharashtra State” (UG, PG programs). Undergraduate (Degree) Admissions Undergraduate (B. Tech.) admissions: Admissions to WCE, Sangli are strictly based on merit only through on-line centralised admission process (CAP) as per the guidelines of Government of Maharashtra and are conducted “The Competent Authority, the Commissioner of State Common Entrance Test Cell, Maharashtra State”. Eligibility and Entrance Test: Please refer website https://www.mahacet.org. , https://mhtcet2020.mahaonline.gov.in/ List of document required for admission: Please refer Link: https://mhtcet2020.mahaonline.gov.in/Content/PDF/News/Documents_Required_for_Admissi ons_to_Engineering_Pharmacy_Agriculture_Fisheries_and_Dairy_Technology_Courses.pdf Admission Process: Please refer to website https://www.mahacet.org and http://www.dtemaharashtra.gov.in/index.html. F.Y. B.Tech Admission (CAP) Related old Links 2019-20 Admission Link: https://fe2019.mahacet.org/staticpages/homepage.aspx -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Dealing with Dirt and the Disorder of Development: Managing Rubbish in Urban Pakistan

LSE Research Online Article (refereed) Jo Beall Dealing with dirt and the disorder of development: managing rubbish in urban Pakistan Original citation: Beall, Jo (2006) Dealing with dirt and the disorder of development: managing rubbish in urban Pakistan. Oxford development studies, 34 (1). pp. 81-97. Copyright © 2006 Taylor and Francis Group. This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/2900 Available online: December 2007 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the publisher’s version remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk Contact LSE Research Online at: [email protected] Dealing with Dirt and the Disorder of Development: Managing Rubbish in Urban Pakistan1 Jo Beall London School of Economics Abstract This article unveils the different ‘thought worlds’ that inform urban development policy and the reality of urban service delivery in Faisalabad, Pakistan’s third largest city.