The Eurasian Hobby Berlin and the Area Around Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress in the Development of an Eurasian-African Bird Migration Atlas

CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP13/Inf.20 MIGRATORY 10 February 2020 SPECIES Original: English 13th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Gandhinagar, India, 17 - 22 February 2020 Agenda Item 25 PROGRESS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN EURASIAN-AFRICAN BIRD MIGRATION ATLAS (Submitted by the European Union of Bird Ringing (EURING) and the Institute of Avian Research) Summary: The African-Eurasian Bird Migration Atlas is being developed under the auspices of CMS in the framework of a Global Animal Migration Atlas, of which it constitutes a module. The African-Eurasian Bird Migration Atlas is being developed and compiled by the European Union of Bird Ringing (EURING) under a Project Cooperation Agreement (PCA) between the CMS Secretariat and the Institute of Avian Research, acting on behalf of EURING. The development of the African-Eurasian Bird Migration Atlas is funded with the contribution granted by the Government of Italy under the Migratory Species Champion Programme. This information document includes a progress report on the development of the various components of the project. The project is expected to be completed in 2021. UNEP/CMS/COP13/Inf.20 Eurasian-African Bird Migration Atlas progress report February 2020 Stephen Baillie1, Franz Bairlein2, Wolfgang Fiedler3, Fernando Spina4, Kasper Thorup5, Sam Franks1, Dorian Moss1, Justin Walker1, Daniel Higgins1, Roberto Ambrosini6, Niccolò Fattorini6, Juan Arizaga7, Maite Laso7, Frédéric Jiguet8, Boris Nikolov9, Henk van der Jeugd10, Andy Musgrove1, Mark Hammond1 and William Skellorn1. A report to the Convention on Migratory Species from the European Union for Bird Ringing (EURING) and the Institite of Avian Research, Wilhelmshaven, Germany 1. British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford, IP24 2PU, UK 2. -

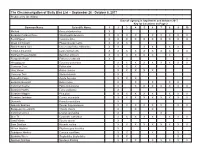

The Circumnavigation of Sicily Bird List -- September 26

The Circumnavigation of Sicily Bird List -- September 26 - October 8, 2017 Produced by Jim Wilson Date of sighting in September and October 2017 Key for Locations on Page 2 Common Name Scientific Name 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X Yellow-legged Gull Larus michahellis X X X X X X X X X X Northern House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X European Robin Erithacus rubecula X X Woodpigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X Common Coot Fulica atra X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X Bonnelli's Eagle Aquila fasciata X X X Eurasian Buzzard Buteo buteo X X X X X Common Kestrel Falco tinnunculus X X X X X X X X Eurasian Hobby Falco subbuteo X Eurasian Magpie Pica pica X X X X X X X X Eurasian Jackdaw Corvus monedula X X X X X X X X X Dunnock Prunella modularis X Spanish Sparrow Passer hispaniolensis X X X X X X X X European Greenfinch Chloris chloris X X X Common Linnet Linaria cannabina X X Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus X X X X X X X X Sand Martin Riparia riparia X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X Willow Warbler Phylloscopus trochilus X Subalpine Warbler Curruca cantillans X X X X Eurasian Wren Troglodytes troglodytes X X X Spotless Starling Spotless Starling X X X X X X X X Common Name Scientific Name 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sardinian Warbler Curruca melanocephala X X X X -

Birds Versus Bats: Attack Strategies of Bat-Hunting Hawks, and the Dilution Effect of Swarming

Supplementary Information Accompanying: Birds versus bats: attack strategies of bat-hunting hawks, and the dilution effect of swarming Caroline H. Brighton1*, Lillias Zusi2, Kathryn McGowan2, Morgan Kinniry2, Laura N. Kloepper2*, Graham K. Taylor1 1Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PS, UK. 2Department of Biology, Saint Mary’s College, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA. *Correspondence to: [email protected] This file contains: Figures S1-S2 Tables S1-S3 Supplementary References supporting Table S1 Legend for Data S1 and Code S1 Legend for Movie S1 Data S1 and Code S1 implementing the statistical analysis have been uploaded as Supporting Information. Movie S1 has been uploaded to figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11823393 Figure S1. Video frames showing examples of attacks on lone bats and the column. (A,B) Attacks on the column of bats, defined as an attack on one or more bats within a cohesive group of individuals all flying in the same general direction. (C-E) Attacks on a lone bat (circled red), defined as an attack on an individual that appeared to be flying at least 1m from the edge of the column, and typically in a different direction to the swarm. (F) If an attack occurred in a volume containing many bats, but with no coherent flight direction, then this was also categorised as an attack on a lone bat, rather than as an attack on the swarm. Figure S2 Video frames used to estimate the proportion of bats meeting the criteria for classification as lone bats. -

Migratory Birds of Ladakh a Brief Long Distance Continental Migration

WORLD'S MIGRATORY BIRDS DAY 08 MAY, 2021 B R O W N H E A D E D G U L L MIGRATORY BIRDS OF LADAKH A BRIEF LONG DISTANCE CONTINENTAL MIGRATION the Arctic Ocean and the Indian Ocean, and comprises several migration routes of waterbirds. It also touches “West Asian- East African Flyway”. Presence of number of high-altitude wetlands (>2500 m amsl altitude) with thin human population makes Ladakh a suitable habitat for migration and breeding of continental birds, including wetlands of very big size (e.g., Pangong Tso, Tso Moriri, Tso Kar, etc.). C O M M O N S A N D P I P E R Ladakh provides a vast habitat for the water birds through its complex Ladakh landscape has significance network of wetlands including two being located at the conjunction of most important wetlands (Tso Moriri, four zoogeographic zones of the world Tso Kar) which have been designated (Palearctic, Oriental, Sino-Japanese and as Ramsar sites. Sahara-Arabian). In India, Ladakh landscape falls in Trans-Himalayan Nearly 89 bird species (long distance biogeographic zone and two provinces migrants) either breed or roost in (Ladakh Mountains, 1A) and (Tibetan Ladakh, and most of them (59) are Plateau, 1B). “Summer Migrants”, those have their breeding grounds here. Trans-Himalayan Ladakh is an integral part of the "Central Asian Flyway" of migratory birds which a large part of the globe (Asia and Europe) between Ladakh also hosts 25 bird species, during their migration along the Central Asian Flyway, as “Passage Migrants” which roost in the region. -

Birding on the Roof of the World Promoting Low-Impact Nature Tourism for Conservation and Livelihoods in the Hindu Kush Karakoram Pamir Landscape

HKPL INITIATIVE Birding on the roof of the world Promoting low-impact nature tourism for conservation and livelihoods in the Hindu Kush Karakoram Pamir Landscape Photo: Imran Shah Landscape ecology and biodiversity The region’s forests, wetlands, The transboundary Hindu Kush Karakoram Pamir rangelands, and peatlands serve as Landscape (HKPL) – a biodiversity-rich location spanning natural habitat for a wide variety of parts of Afghanistan, China, Pakistan, and Tajikistan – is home to six protected areas: the Wakhan National Park resident and migratory birds. of Afghanistan; the Taxkorgan Nature Reserve of China; the Broghil, Qurumber, and Khunjerab national parks of Pakistan; and the Zorkul Nature Reserve of Tajikistan. birds. The landscape is an important migratory corridor, Together, these physically connected protected areas cover hosting staging and breeding grounds for several species 33,000 square kilometres, just under half of the total area of including the Critically Endangered sociable lapwing and the the landscape. Endangered steppe eagle, saker falcon, and Pallas’s fish eagle. As part of the western Hindu Kush Himalaya, the HKPL lies As ecological indicators of habitat quality, birds provide at a junction of several important biogeographical regions. important information about ecosystem health for A unique diversity of flora and fauna, including 306 bird conservation planning, setting management priorities, and species, flourish in its cold desert ecosystem. measuring the success of restoration efforts. In the HKPL, Birds are an integral part of the HKPL’s biodiversity. The the six contiguous protected areas present opportunities for region’s wetlands, rangelands, and peatlands are the transboundary cooperation for biodiversity conservation and natural habitat of a wide variety of resident and migratory sustainable development. -

Red Necked Falcon

Ca Identifi cation Habit: The Red-necked Falcon is an arboreal and Features: Cultural Aspects: aerial crepuscular bird. Lives and hunts in pairs. In ancient India this falcon was Flight is fast and straight. It is capable of hovering. esteemed by falconers as it hunts in 1st and 4th primary pairs, is easily trained and is obedient. Distributation: India upto Himalayan foothills and subequal. 2nd and 3rd It took birds as large as partridges. terrai; Nepal, Pakistan and BanglaDesh. South of primary subequal. In ancient Egypt, Horus, was the Sahara in Africa. Crown and cheek stripe falcon-headed god of sun, war and chestnut. protection and was associated with Habitat: Keeps to plain country with deciduous the Pharoahs. vegetation, hilly terrain, agricultural cropland with Bill plumbeous, dark groves, semiarid open scrub country and villages. tipped. Avoids forests. Iris brown. Related Falcons: Behaviour: Resident falcon with seasonal Cere, orbital skin, legs and Common Kestrel, Shaheen and Laggar Falcon are residents . The movements that are not studied. Swiftly chases feet yellow. Peregrine, Eurasian Hobby and Merlin are migrants. Red-legged crows, kites and other raptors that venture near its Falcon is extra-limital and is not recorded from India. nest. Shrill call is uttered during such frantic chase. Utters shrill and piercing screams ki ki ki ki, with diff erent calls, grates and trills for other occasions. Female feeds the male during the breeding season. A pair at sunrise roosting on the topmost perches of a tall tree Claws black. Tail broad with black sub-terminal band. Thinly barred abdomen MerlinM Common Kestrel Laggar Falcon Amur Falcon and fl anks. -

Kanha Bird Checklist (Pdf)

KANHA BIRD SURVEY - CHECKLIST Expected Species eBird 'English (India)' Local name eBird scientific name status Detection 17/03 18/03 19/03 Lesser Whistling Duck Dendrocygna javanica R Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea W Cotton Pygmy-Goose Nettapus coromandelianus R Gadwall Anas strepera W Eurasian Wigeon Anas penelope W Indian Spot-billed Duck Anas poecilorhyncha R Northern Pintail Anas acuta W Garganey Anas querquedula W Green-winged Teal (Common Teal) Anas crecca W Indian Peafowl Pavo cristatus R Red Spurfowl Galloperdix spadicea R Jungle Bush-Quail Perdicula asiatica R Painted Francolin Francolinus pictus R H Grey Francolin Francolinus pondicerianus R H Red Junglefowl Gallus gallus R H Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis R Asian Openbill Anastomus oscitans R Black Stork Ciconia nigra W Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus R Lesser Adjutant Leptoptilos javanicus R Little Cormorant Microcarbo niger R Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo R Indian Cormorant (Indian Shag) Phalacrocorax fuscicollis R Oriental Darter Anhinga melanogaster R Grey Heron Ardea cinerea R Purple Heron Ardea purpurea R Great Egret Ardea alba R Intermediate Egret Mesophoyx intermedia R Little Egret Egretta garzetta R Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis R Indian Pond-Heron Ardeola grayii R Threskiornis Black-headed Ibis melanocephalus R Red-naped Ibis (Indian Black Ibis) Pseudibis papillosa R Black-shouldered Kite Elanus caeruleus R (Black-winged Kite) Crested (Oriental) Honey Buzzard Pernis ptilorhynchus R White-rumped Vulture Gyps bengalensis R Indian Vulture (Indian Long-billed -

Madrid Hot Birding, Closer Than Expected

Birding 04-06 Spain2 2/9/06 1:50 PM Page 38 BIRDING IN THE OLD WORLD Madrid Hot Birding, Closer Than Expected adrid is Spain’s capital, and it is also a capital place to find birds. Spanish and British birders certainly know M this, but relatively few American birders travel to Spain Howard Youth for birds. Fewer still linger in Madrid to sample its avian delights. Yet 4514 Gretna Street 1 at only seven hours’ direct flight from Newark or 8 ⁄2 from Miami, Bethesda, Maryland 20814 [email protected] Madrid is not that far off. Friendly people, great food, interesting mu- seums, easy city transit, and great roads make central Spain a great va- cation destination. For a birder, it can border on paradise. Spain holds Europe’s largest populations of many species, including Spanish Imperial Eagle (Aquila heliaca), Great (Otis tarda) and Little (Tetrax tetrax) Bustards, Eurasian Black Vulture (Aegypius monachus), Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio), and Black Wheatear (Oenanthe leucura). All of these can be seen within Madrid Province, the fo- cus of this article, all within an hour’s drive of downtown. The area holds birding interest year-round. Many of northern Europe’s birds winter in Spain, including Common Cranes (which pass through Madrid in migration), an increasing number of over-wintering European White Storks (Ciconia ciconia), and a wide variety of wa- terfowl. Spring comes early: Barn Swallows appear by February, and many Africa-wintering water birds arrive en masse in March. Other migrants, such as European Bee-eater (Merops apiaster), Common Nightingale (Luscinia megarhynchos), and Golden Oriole (Oriolus ori- olous), however, rarely arrive before April. -

Avifaunal Baseline Assessment of Wadi Al-Quff Protected Area and Its Vicinity, Hebron, Palestine

58 Jordan Journal of Natural History Avifaunal baseline assessment of Wadi Al-Quff Protected Area and its Vicinity, Hebron, Palestine Anton Khalilieh Palestine Museum of Natural History, Bethlehem University, Bethlehem, Palestine Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Birds of Wadi Al-Quff protected area (WQPA) were studied during the spring season of 2014. A total of 89 species of birds were recorded. Thirty species were found to breed within the protected area (24 resident and 6 summer breeders), while the others were migratory. Three species of raptors (Long legged Buzzard, Short-toed Eagle and the Hobby) were found to breed within man-made afforested area, nesting on pine and cypress trees. Within the Mediterranean woodland patches, several bird species were found nesting such as Cretzschmar's Bunting, Syrian Woodpecker, Sardinian Warbler and Wren. Thirteen species of migratory soaring birds were recorded passing over WQPA, two of them (Egyptian Vulture and Palled Harrier) are listed by the IUCN as endangered and near threatened, respectively. In addition, several migratory soaring birds were found to use the site as a roosting area, mainly at pine trees. Key words: Birds; Palestine; Endangered species. INTRODUCTION The land of historical Palestine (now Israel, West bank and Gaza) is privileged with a unique location between three continents; Europe, Asia, and Africa, and a diversity of climatic regions (Soto-Berelov et al., 2012). For this reason and despite its small area, a total of 540 species of bird were recorded (Perlman & Meyrav, 2009). In addition, Palestine is at the second most important migratory flyway in the world. Diverse species of resident, summer visitor breeders, winter visitor, passage migrants and accidental visitors were recorded (Shirihi, 1996). -

Aerial Attack Strategies of Bat-Hunting Hawks, and the Dilution Effect of Swarming

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.11.942060; this version posted July 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Aerial attack strategies of bat-hunting hawks, and the dilution effect of swarming Caroline H. Brighton1*, Lillias Zusi2, Kathryn McGowan2, Morgan Kinniry2, Laura N. Kloepper2*, Graham K. Taylor1* 1Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PS, UK. 2Department of Biology, Saint Mary’s College, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA. *Correspondence to: [email protected] or [email protected] Keywords: dilution effect, confusion effect, predator-prey interaction, swarming, Buteo swainsoni, Tadarida brasiliensis Lay summary Bats emerging by daylight from a massive desert roost are able to minimise their predation risk by maintaining tight column formation, because the hawks that attack them target stragglers disproportionately often. Whereas the predation risk of a bat therefore depends on how it maintains its position within the swarm, the catch success of a hawk depends on how it maneuvers to attack. Catch success is maximised by executing a stooping dive or a rolling grab. Abstract Aggregation behaviors can often reduce predation risk, whether through dilution, confusion, or vigilance effects, but these effects are challenging to measure under natural conditions, involving strong interactions between the behaviors of predators and prey. Here we study aerial predation of massive swarms of Brazilian free-tailed bats Tadarida brasiliensis by Swainson’s hawks Buteo swainsoni, testing how the behavioral strategies of predator and prey influence catch success and predation risk. -

2019 Trip Report Available Here

Ronda and the Straits – the unknown Vulture spectacle! Friday 18th October – Thursday 24th October Report by Beth Aucott www.ingloriousbustards.com Friday 18th October After an early start we arrived at Malaga airport about midday where we met Niki and the first member of our group Margaret. After introductions, the four of us set off in one of the vehicles whilst Simon met the rest of the group and it wasn’t long before we were travelling in convoy on our way to our first base, Huerta Grande - a beautiful eco-lodge snuggled into cork-oak woodland. Over a light lunch, and a glass of wine, we met the rest of the group, Alexia, Glenn, Carla, Chris and Colin as we watched Crested Tits come into the feeders. It felt bizarre to be watching these funky little birds in shorts and t-shirt when then the only time I’d seen them before had been in the snow in Scotland! We had time to settle in and have a quick wander around the grounds. Our list started to grow with sightings of Nuthatch, Short-toed Treecreeper, Long-legged Buzzard, Booted Eagle, Sand Martin, House Martin, Barn and Red-rumped Swallow. Fleeting views of Two-tailed Pasha and Geranium Bronze also went down well as welcome additions to the butterfly list. We then headed out to Punta Carnero and spent some time at a little viewpoint on the coast. From here we watched a couple of Ospreys fishing as we looked across the straits to Africa. Red-rumped Swallows and Crag Martins whizzed overhead, sharing the sky with Hobby, Sparrowhawk and Peregrine. -

Life Science Journal 2014;11(7) 809

Life Science Journal 2014;11(7) http://www.lifesciencesite.com Histomophological studies on the stomach of Eurasian Hobby (Falconinae: Falco subbuteo, Linnaeus 1758) and its relation with its feeding habits Mohamed M. A. Abumandour Anatomy and Embryology Department, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Alexandria University, Egypt [email protected] Abstract: The avian stomach was a muscular organ, located between the esophagus and the intestine and it was consisted of two parts; the proventriculus and the ventriculus as reported in many text books and previous articles. A morphological study of stomach was carried out, grossly and under light microscopy on ten adult normal healthy Eurasian Hobbies. The stomach was constituted by two chambers: proventriculus and gizzard. The proventriculus was elongated fusiform shaped organ and extended from the level of 2nd intercostal space to the level of 4th rib, while the ventricular resembles a biconvex lens and was extended from the level of 4th rib to the level of 7th rib. There is no any proventricular papilla on the gastric epithelium surface. Both, the mucous tunic of the proventriculus and of the ventriculus present folds were lined by simple columnar epithelium. The tunica mucosa of the proventriculus was extensively folded due to the presence of well-developed longitudinal muscle bundles. The Eurasian Hobby stomach ischaracterized by the absence of the isthmus. There are fourventricular muscles that radiating from a powerful fan-shaped tendinous center; two thick and two thin muscles. The luminal surface of the ventriculus have cuticle, which was sloughed and shed small fine area around the pyloric opening and very thin membrane and highly closely adherent to the lining surface of gizzard.