Alice Williams the Production of Luck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear Colleagues, It Is with Great Pleasure

Dear Colleagues, It is with great pleasure that the University of Chicago Press presents its Fall 2009 seasonal catalog of Distributed Books for your review. Here you will find upcoming titles from such distributed client presses as Reaktion, Seagull, British Library, The Bodleian Library, Center for American Places, KWS, The National Journal Group, and many more all conveniently searchable by subject. You can also access additional information for each book by clicking on its title. Please do not hesitate to contact us if you are interested in having a closer look at any of these books. And many thanks for your consideration! Mark Heineke Carrie Adams Promotions Director Publicity Manager University of Chicago Press University of Chicago Press 1427 E. 60th Street 1427 E. 60th Street Chicago IL 60637 Chicago IL 60637 [email protected] [email protected] DISTRIBUTED BOOKS Reaktion Books 105 Seagull Books 119 Architects Research Foundation 134 British Library 135 Planners Press, American Planning Association 141 National Journal Group 142 Bodleian Library, University of Oxford 144 Dana Press 147 American Meteorological Society 148 Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago 149 Prickly Paradigm Press 153 Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University 154 Verlag Scheidegger and Spiess 155 Swan Isle Press 158 The Karolinum Press, Charles University Prague 159 Smart Museum of Art 160 KWS Publishers 161 Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs 165 Intellect Books 166 Brigham Young University 170 University of Alaska Press 170 University of Chicago Center in Paris 175 Amsterdam University Press 176 University of Exeter Press 184 Campus Verlag 188 Liverpool University Press 191 University of Wales Press 198 University of Scranton Press 206 Eburon Publishers, Delft 209 Fondazione Rossini 210 MELS VAN DRIEL Manhood The Rise and Fall of the Penis Translated by Paul Vincent The ancient Greeks paraded enormous sculptural replicas in annual celebration. -

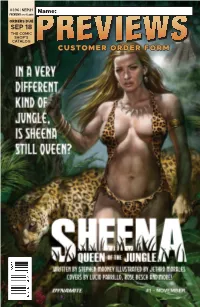

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

JULIANA VILLAGE July 2018

Juliana Village Activities Program – July 2018 JULIANA VILLAGE RESIDENTS’ NEWSLETTER July 2018 Juliana Village Activities Program – July 2018 Mon 2nd - Monthly Shopping Trip to Southgate at 10:30am with Shire Mini Bus. - Renata Nail Appointments - BINGO with Lorna at 1:45pm Tue 3rd - Music at 10:30am & Men’s Shed 10am -12pm - Music Therapy with Jenni at 2:15pm in GC Wed 4th - Podiatry Day - 9:30am in Georges Centre, - Devotion with Tony at 1:45pm Thurs 5th - Hairdresser Day, - Laughter Yoga at 2pm in GC Fri 6th - Painting Therapy with Janine at 10:30am, - Short Bus Trip at 1:15pm with Shire Mini Bus. - Residents Committee Meeting 2pm Mon 9th - BINGO with Lorna at 1:45pm , Tue 10th -Library Day , - Music at 10:30am, -Monthly Lunch Outing to: Bundeena Memorial RSL Club-$30pp, Bus departs at 10:30am with Activus Wed 11th -Devotion with Tony at 1:45pm in GC Thurs 12th - Hairdresser Day, - Birthday Party with Bollywood Dancers at 2:00pm Fri 13th - Painting Therapy with Janine at 10:30am Mon 16th - Renata Nail Appointments - BINGO with Lorna at 1:45pm Tue 17th - Music Sing-a-long at 10:30am & Men’s Shed with Tony 10am-12pm Wed 18th - Podiatry Day - Hairdresser in Today - Devotion with Tony at 1:45pm in GC Thurs 19th - Christmas in July Event at Panorama House, Bus Departs at 10:30am Fri 20th - Painting Therapy with Janine at 10:30am Mon 23rd h - BINGO with Lorna at 1:45pm , - Renata Nail Appointments Tue 24th - Library Day , - Music Sing-a-long & Men’s Shed 10am-12pm Wed 25th Devotion with Tony at 1:45pm in GC Thurs 26th - Hairdresser Day -Happy Hour at 2pm Fri 27th -Painting Therapy with Janine at 10:30am, - Short Shopping Trip to Menai Marketplace at 1:15pm with Activus . -

Index of Concepts in Eugenio Barba's Writings

NORDISK TEATERLABORATORIUM – ODIN TEATRET - WWW.ODINTEATRET.DK INDEX OF CONCEPTS IN EUGENIO BARBA’S WRITINGS LLUÍS MASGRAU CRITERIA . Eugenio Barba’s written work is a laboratory of concepts. Beyond the numerous texts and the apparent variety of subjects dealt with, there exists in his work a series of inner lines of strength that structure and amalgamate it in a coherent whole. These lines of strength are composed of a range of concepts that Barba takes up and elaborates from one text to another. These concepts move through his writings via innumerable intellectual peripetia. This document is an index of concepts with the respective bibliographical indications corresponding to Barba’s written work. The bibliographical indications don't refer to the places where he quotes the concepts in question, but to the fragments where he formulates and elaborates them. The document includes all the concepts that have a precise and concrete formulation in Barba’s writings, even if they have only one bibliographical reference. The document, however, does not include a whole series of very important concepts in his work which do not possess a precise formulation: "exile", "ethics", "ethos", "journey", "transcendence". This deliberate vagueness constitutes a kind of music or background throughout Barba’s written work. The title is always in English. If the text doesn't exist in English, it is given in the language of its first publication. Article titles are written in lower case letters, book titles in capitals. The references included in every concept are in chronological order, from the most recent to the oldest. Barba’s text, in which the most elaborate formulation of every concept appears, is in bold. -

Vinyl Records for Sale

VINYL RECORDS FOR SALE Updated: 14.09.2021 SIGNS & SYMBOLS: Artist / title / music / year of first publishing / country of origin / issue / label / country of issue / gradings (record / cover) / remarks / price in Euro To get the price in US Dollars = Price in Euro x 1,15 Music: age - new age avn - avantgarde avj - avantgarde/jazz avr - avantgarde/rock bea - beat bgr - bluegrass blu - blues blr - blues rock brs - brass rock chn - chansons ctr - country rock dis - disco eas - easy listening elm - electronic/meditation music fnk - funky fol - folk flr - folk rock hrd - hard rock hvm - heavy metal jaz - jazz j+r - jazz rock new - contemporary music, new music old - early music ork - orchestral music ost - original soundtrack p+r - poprock pjr - progressive jazz rock pop - pop prg - progressive rock prf - progressive folk rock prh - progressive hard rock psy - psychedelic pnk - punk reg - reggae roc - rock rnr - rock and roll rnb - rhythm and blues sgr - singer / songwriter ska - ska, rockabilly, psychobilly sou - soul slr - soulrock srf - surf music sth - southern rock swi - swing syn - synthesizer rock tec - techno trd - traditional jazz ujr - underground jazzrock und - underground music unf - underground folk unj - underground jazz unr - underground rock var - variety music Issue: or - original, first issue ri - reissue with different cover ro - reissue in original cover YY - release’s year of this reissue P.J. - Polish Jazz series Nr... APB - „Archiv of Polish Beat” series Gradings: (record first /then cover) m (mint - the record looks -

Released 19Th August 2020 BOOM!

Released 19th August 2020 BOOM! STUDIOS JAN201335 ANGEL SEASON 11 LIBRARY ED HC APR201364 FAITHLESS II #3 CVR A LLOVET APR201365 FAITHLESS II #3 CVR B EROTICA CONNECTING VAR JUN200787 FIREFLY #19 CVR A MAIN ASPINALL JUN200788 FIREFLY #19 CVR B KAMBADAIS VAR FEB201290 GO GO POWER RANGERS TP VOL 07 APR201373 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #10 CVR A FINDEN APR201374 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #10 CVR B MATTHEWS CO APR201371 ONCE & FUTURE #10 FEB201340 OVER GARDEN WALL SOULFUL SYMPHONIES TP JUN200764 POWER RANGERS DRAKKON NEW DAWN #1 CVR A MAIN SECRET JUN200767 POWER RANGERS DRAKKON NEW DAWN #1 FOIL VAR JUN208619 POWER RANGERS RANGER SLAYER #1 (2ND PTG) MAR201359 QUOTABLE GIANT DAYS GN JUN208620 SOMETHING IS KILLING CHILDREN #7 (2ND PTG) DARK HORSE COMICS APR200392 ART OF DRAGON PRINCE HC JAN200399 CYBERPUNK 2077 KITSCH PUZZLE JAN200400 CYBERPUNK 2077 NEOKITSCH PUZZLE JUN200310 DRAGON AGE BLUE WRAITH HC DC COMICS MAR200619 BATMAN BY GRANT MORRISON OMNIBUS HC VOL 03 OCT190663 GREEN ARROW LONGBOW HUNTERS OMNIBUS HC VOL 01 DYNAMITE APR201139 BETTIE PAGE #1 KANO LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201140 BETTIE PAGE #1 LINSNER LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201138 BETTIE PAGE #1 YOON LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201266 GEORGE RR MARTIN A CLASH OF KINGS #6 CVR A MILLER APR201267 GEORGE RR MARTIN A CLASH OF KINGS #6 CVR B RUBI APR201154 GREEN HORNET #1 JOHNSON LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201153 GREEN HORNET #1 WEEKS LTD VIRGIN VAR MAR201221 JAMES BOND #6 RICHARDSON LTD VIRGIN CVR MAR201231 KILLING RED SONJA #3 CVR A WARD MAR201232 KILLING RED SONJA #3 CVR B GEDEON HOMAGE APR201283 -

Humanities Festival Is Varied Program

FRIDAY, APRIL 30, 1976 T H E BENNETT BANNER Page Five Humanities Festival Is Varied Program Students learn to make clay pots under the direction of ceramist Karen Reed. photo by Virginia Tucker I Belinda DeFoor (L) and 'Twinkle' Richmond (R) try table Valena M. Williams, '43, (L) and Stella L. Britton, '73, (R) loom belonging to guest weaver Nancy Morton. share experiences with students. photo by Virginia Tucker photo by Cheryl E. Johnson Banner Staffer of 1940% Williams, Speaks Maggie Smoot (center) demonstrates card weaving to art teacher Alma Adams (L) and students. Alumnae Return To Participate in Humanities Salute photo by Virginia Tucker As a part of the W omen’s panel discussion in Black Hall on Mrs. Britton has worked in Studies Program and in conjunc “Leadership Opportunities for A.I.D.’s Office for Urban Develop tion with the Humanities Festival, Women in International Service.” ment and the Africa Bureau and two Bennett graduates appeared At 2 p.m., Mrs. Williams con is presently preparing analyses re at Bennett on April 21 in a semi ducted a media workshop. After lating to development policies, aid nar on the preparation of women the workshop, Mrs. Britton met in flows, and financial institutions at for leadership roles in interna formally with students. the Program and Policy Coordi tional service. Both women have had extensive nation Bureau. She received her experience in Africa, Under the M.A. degree in 1975 from the Mrs. Stella L. Britton, ’73, an Bennett co-op program Mrs. Brit School of Advanced International economist at the Program and ton served as an economist intern Studies, Johns Hopkins Univer Policy Coordination Bureau, with A.I.D. -

Download Download

FGSDGSDFGDFGFDGFGSDGSDFGDFGFDG JTA - Journal of Theatre Anthropology 1 1 JTA JTA J J OURNA OURNA OURNA OURNA T T AT AT AT AT A A NTOPOLOGY NTOPOLOGY JOURNAJOURNA TATTAT ANTOPOLOGYANTOPOLOGY T T ISSN 2784-8167ISSN 2784-8167 ISBN 978-88-5757-809-5ISBN 978-88-5757-809-5 MIMESIS MIMESIS 1 2021 1 2021 Mimesis EdizioniMimesis Edizioni www.mimesisedizioni.itwww.mimesisedizioni.it 22,00 euro22,00256 euro 9 7 8 8 895 77 8587885079 55 7 8 0 9 5 257 JTA JOURNAL OF THEATRE ANTHROPOLOGY NUMBER 1 - THE ORIGINS 2021 MIMESIS 258 Journal of Theatre Anthropology Annual Journal founded by Eugenio Barba JTAJTA In collaboration with International School of Theatre Anthropology (ISTA), JOURNAL OF THEATRE ANTHROPOLOGY Odin Teatret Archives (OTA), Centre for Theatre Laboratory Studies (CTLS) Department of Dramaturgy Founded by Eugenio Barba Aarhus University With the support of NUMBER 1 - THE ORIGINS Fondazione Barba Varley March 2021 © 2021 Journal of Theatre Anthropology and Author(s) This is an open access journal Editor distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) Eugenio Barba (Odin Teatret, Denmark) Journal’s website: https://jta.ista-online.org Printed copies are available at the Publisher’s website Managing Editor Leonardo Mancini (Verona University, Italy) Editorial correspondence and contributions should be sent Editorial Board to the managing editor Leonardo Mancini: [email protected] Simone Dragone (Genoa University, Italy / Odin Teatret Archives) Rina Skeel (Odin Teatret, Denmark) Julia Varley -

1 Azərbaycan Respublikasi Mədəniyyət Və Turizm Nazirliyi M.F.Axundov Adina Azərbaycan Milli Kitabxanasi Yeni K

AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASI MƏDƏNİYYƏT VƏ TURİZM NAZİRLİYİ M.F.AXUNDOV ADINA AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ KİTABXANASI YENİ KİTABLAR Annotasiyalı biblioqrafik göstərici 2009 Buraxılış IV B A K I – 2010 1 AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASI MƏDƏNİYYƏT VƏ TURİZM NAZİRLİYİ M.F.AXUNDOV ADINA AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ KİTABXANASI YENİ KİTABLAR 2009-cu ilin dördüncü rübündə M.F.Axundov adına Milli Kitabxanaya daxil olan yeni kitabların annotasiyalı biblioqrafik göstəricisi Buraxılış IV BAKI - 2010 2 Tərtibçilər: L.Talıbova N.Rzaquliyeva Baş redaktor: K.Tahirov Redaktor: T.Ağamirova Yeni kitablar: biblioqrafik göstərici /tərtib edənlər L.Talıbova [və b.]; baş red. K.Tahirov; red. T.Ağamirova; M.F.Axundov adına Azərbаycан Milli Kitabxanası.- B., 2009.- Buraxılış IV. - 356 s. © M.F.Axundov ad. Milli Kitabxana, 2009 3 Təbiət elmləri 1. Б1 Azərbaycan-bənzərsiz təbiət səltənəti [Mətn] /baş A99 red. H.Bağırov; foto H.Müller; dizayn L.Salamova.- Bakı: Çaşıoğlu, 2006.- 216 s. Kitabda Azərbaycanın canlı geologiyası, landşaftları, yarımsəhraları, heyvandarlıq və ətraf mühiti, parkları və qoruqları haqqında geniş məlumat verilmişdir. 2. Б Orucov, F.M. Təbiətşünaslığın əsasları [Mətn]: ali O-58 təhsilin bakalavr pilləsi üçün dərslik /Firudin Orucov; elmi red. R.Z.Sultanov; Azərb. Resp. TN, Təhsil problemləri institutu.- Bakı: BQU, 2005- 324 s. 3. 2-783389 Карпенков, С.Х. Концепции современного естествознания [Текст]: учебник для студентов вузов /Степан Карпенков; рец. М.В.Вальяно, В.А.Шахнов; предис. к одиннадцатому изд. С.Х.Карпенков.- М.: КноРус, 2009.- 672 с. 4. 2-783772 Куклев, Ю.И. Физическая экология [Текст]: учебное пособие для студ. техн. спец. /Юрий Куклев; рец. В.Т.Медведев.- М.: Высшая школа, 2008.- 392 с. В книге впервые обобщены, систематизированы и рассмотрены физические поля естественного и техногенного происхождения, являющиеся одним из главных абиотических факторов окружающей среды. -

Twisted Trails of the Wold West by Matthew Baugh © 2006

Twisted Trails of the Wold West By Matthew Baugh © 2006 The Old West was an interesting place, and even more so in the Wold- Newton Universe. Until fairly recently only a few of the heroes and villains who inhabited the early western United States had been confirmed through crossover stories as existing in the WNU. Several comic book miniseries have done a lot to change this, and though there are some problems fitting each into the tapestry of the WNU, it has been worth the effort. Marvel Comics’ miniseries, Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather was a humorous storyline, parodying the Kid’s established image and lampooning westerns in general. It is best known for ‘outing’ the Kid as a homosexual. While that assertion remains an open issue with fans, it isn’t what causes the problems with incorporating the story into the WNU. What is of more concern are the blatant anachronisms and impossibilities the story offers. We can accept it, but only with the caveat that some of the details have been distorted for comic effect. When the Rawhide Kid is established as a character in the Wold-Newton Universe he provides links to a number of other western characters, both from the Marvel Universe and from classic western novels and movies. It draws in the Marvel Comics series’ Blaze of Glory, Apache Skies, and Sunset Riders as wall as DC Comics’ The Kents. As with most Marvel and DC characters there is the problem with bringing in the mammoth superhero continuities of the Marvel and DC universes, though this is not insurmountable. -

Memoria Completa

1 AGRADECIMIENTOS Eva López, Juana Jara, Javier Fernández Río, Juan Majada y Pablo Priesca. Edita Caja Rural de Asturias Diseño, maquetación y contenidos Cronistar Fotografías Carlos Rodríguez Imprime Gráficas Eujoa S.A. Depósito Legal AS 2246-2003 www.fundacioncajaruraldeasturias.com 3 ÍNDICE Quiénes somos 4 Carta del Presidente 6 Laboratorio de oncología 8 Con los que avanzan 16 Ingeniero del año 38 Todo por aprender 42 Creciendo juntos 52 Artes plásticas 60 Libros y publicaciones 70 Música 78 Deporte 88 Nunca caminarán solos 102 Nuestro medio rural 122 Desglose económico 140 Órganos de Gobierno 142 5 Quiénes somos Nuestros valores Somos una cooperativa de crédito, una entidad financiera que » Devolver la CONFIANZA que nuestros socios y clientes nos desde 1965 provee de productos y servicios financieros al mer- han confiado. cado asturiano, destinatario de nuestra actuación directa. Ejer- cemos una banca de proximidad sin olvidar que nuestra asocia- » Establecer un COMPROMISO con los valores de nuestra co- ción con otras Cajas Rurales en el Banco Cooperativo Español munidad. nos permite realizar la actividad desde un concepto más global. » Defender un desarrollo basado en la ÉTICA social y empresa- La confianza, aspecto clave en la relación entre una entidad de rial. ahorro y sus clientes, la traducimos en una combinación de bue- nas prácticas bancarias y valores éticos al servicio de los intere- » Vocación de SERVICIO a la sociedad con el objetivo de mejo- ses financieros de nuestros socios respaldada por la fortaleza de rar su calidad de vida. nuestros recursos propios generados con una eficiente gestión. » Potenciar la CERCANÍA para desarrollar actividades destina- das a todos los segmentos de la población con especial dedi- Nuestro compromiso cación al fomento de la economía social y al medio rural. -

Dennis J. Miller of Michigan State University

---11111-111111111--------~S=i educator ) Dennis J. Miller of Michigan State University Dennis with post-doctoral associate Navin Asthana in 2006. BY DAINA M. BRIEDIS WITH JANE L. DEPRIEST Dennis has been a faculty member in the Department of edicated and resolute. If taken without energy, in Chemical Engineering and Materials Science at MSU in East novation, and relationships, these attributes suggest Lansing, Michigan, since completing his doctorate in 1982. Droutine, even monotony, in life. But for Dennis Miller, He has had the same 'Job" for his entire academic career. professor of chemical engineering at Michigan State Uni During that time, Dennis has been successful in cultivating his versity (MSU), life is anything but monotonous. His love of passion for teaching and research, while maintaining a hefty discovery and creative spirit energize him to constantly seek measure of service in the academic and local communities. new opportunities both professionally and personally, and his He has balanced career, family, and faith-all while trying to dedication and resolve have led to a life that is full of diverse keep a healthy perspective on time and resource challenges. experiences and accomplishments. With these traits, Dennis His energy, enthusiasm, and selfless commitment in all as Miller is exemplary in how a typical kid from Toledo, Ohio, pects of life have earned him the affectionate title of "The can become a respected and accomplished teacher, researcher, "Energizer Bunny" among family and friends. His passion and community servant. © Copyright ChE Division of ASEE 2009 82 Chemical Engineering Education for "doing" -and doing things well-is contagious, and has benefited his students, colleagues, family, and the progress of his career.