"Art and Industry" at the Pare Des Buttes Chaumont Ann E. Komara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historique Du Parc Des Buttes-Chaumont

A 175 Parc des Buttes-Chaumont Descriptif général HISTORIQUE DU PARC DES BUTTES-CHAUMONT Par Françoise HAMON, historienne, membre de l’équipe Grünig-Tribel Mai 2001. Publié en ligne avec l’autorisation de l’auteur. Reproduction interdite pour un usage commercial ou professionnel. Historique sous forme de trois chapitres présentés en annexe au descriptif général du concours. Annexe 1 : historique du projet des Buttes-Chaumont Annexe 2 : Liste de la documentation d’archives disponibles relative au parc des Buttes-Chaumont Annexe 3 : Chronologie du parc 1 A 175 Equipe GRUNIG-TRIBEL - Historique du Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, par Françoise HAMON, historienne. I. Annexe 1 : Historique du projet des Buttes Chau- mont a) La genèse Parc des Buttes-Chaumont Descriptif général ⇒ Les origines du jardin paysager Les traités anglais du XVIII˚ siècle consacrés aux jardins ne traitent que des parcs de châteaux et ne portent sur des questions d’esthétique : comment créer des paysages dignes d’être peints, c’est- à-dire pittoresques. En réalité, on cherche surtout, par une rupture subtile avec le paysage rural environnant, à mettre en valeur la demeure aristocratique ainsi que l’exige une société extrêmement hiérarchisée. Autant que les portraits de famille (conversation pieces) destinés à valoriser la lignée, l’aristocratie anglaise apprécie les portraits de maisons (voir le film Meurtre dans un jardin anglais) destinés à renforcer la présence territoriale de leur demeure et sa domination spatiale, dans une tradi- tion encore féodale. Le naturel du jardin paysager sera donc un naturel au second degré, identifiable comme naturel fabriqué. On peut ici jouer sur les mots car ce naturel fabriqué est fondé sur la présence de fabriques : outre les commodités qu’elle offre pour la vie sociale, la multiplication de ces pavillons d’agrément produit des fragments de paysages exotiques (à base de pagodes chinoises ou tentes turques) ou historiques (fondés sur le temple antique ou la ruine médiévale). -

À La Station Visuel De Couverture : La Gare De Saint-Omer, Été 2019

FOCUS DE LA GARE DE SAINT-OMER À LA STATION Visuel de couverture : La gare de Saint-Omer, été 2019. 2 Cliché Carl Peterolff. SOMMAIRE P.4 L’ARRIVÉE DU CHEMIN DE FER P.29 LA GARE À LA RECHERCHE DANS L’AUDOMAROIS d’un secOND SOUFFLE > Contexte général (1945-1979) > Mise en place de la ligne Lille-Calais > La Reconstruction > La première gare de Saint-Omer > L’étiolement du trafic > Un équipement en perte de vitesse P.9 LE PROJET DE NOUVELLE GARE > L’exiguïté des infrastructures existantes P.33 DES DÉFIS NOUVEAUX > Le projet et sa mise en oeuvre (1980-2019) > Une cathédrale ferroviaire > Reconnaissance patrimoniale > Redessiner le quartier > Regain de fréquentation > Modernisation et TGV > L’intégration aux politiques locales P.17 LES GRANDES HEURES DU FERROVIAIRE AUDOMAROIS > La gare des maraîchers P.43 LES LIGNES SECONDAIRES > Voyageurs et marchandises ET LE PATRIMOINE FERROVIAIRE > Une nouvelle population > La ligne Saint-Omer – Boulogne > Les Voies métriques : La ligne Anvin à Calais et Aire – Berck-sur-Mer P.21 UNE INFRASTRUCTURE AU > Modernisation et Fermeture COEUR DES CONFLITS MONDIAUX > Le patrimoine ferroviaire du Pays d’art et > La Grande guerre d’histoire > Le second conflit mondial 3 4 1 L’arrivée DU CHEMIN DE FER dans l’audomarois 2 2. Lors de la construction de la ligne Lille-Calais, Saint-Omer milite pour un contournement du marais par l’ouest mais ses édiles n’obtiennent pas gain de cause. 1848. BAPSO, archives communales, 2O. CONTEXTE GÉNÉRAL MISE EN PLACE DE LA LIGNE LILLE-CALAIS Au XIXème siècle, le transport par voie de Lille et Dunkerque forment une «alliance» chemin de fer s’est développé en France et en qui appuie dès 1843 la mise en place de Europe, grâce à la création des locomotives à l’embranchement vers les ports à partir vapeur. -

Rapport D'activité 2019 Musées D'orsay Et De L'orangerie

Rapport d’activité 2019 Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie Rapport d’activité 2019 Établissement public des musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie Sommaire Partie 1 Partie 3 Les musées d’Orsay Le public, au cœur de la politique et de l’Orangerie : des collections de l’EPMO 57 exceptionnelles 7 Un musée ouvert à tous 59 La vie des collections 9 L’offre adulte et grand public 59 Les acquisitions 9 L’offre de médiation famille et jeune Le réaccrochage des collections permanentes 9 public individuel 60 Les inventaires 10 L’offre pour les publics spécifiques 63 Le récolement 22 L’éducation artistique et culturelle 64 Les prêts et dépôts 22 Les outils numériques 65 La conservation préventive et la restauration 23 Les sites Internet 65 Le cabinet d’arts graphiques et de photographies 25 Les réseaux sociaux 65 Les accrochages d’arts graphiques Les productions audiovisuelles et numériques 66 et de photographies 25 Le public en 2019 : des visiteurs venus L’activité scientifique 30 en nombre et à fidéliser 69 Bibliothèques et documentations 30 Des records de fréquentation en 2019 69 Le pôle de données patrimoniales digitales 31 Le profil des visiteurs 69 Le projet de Centre de ressources La politique de fidélisation 70 et de recherche 32 Les activités de recherche et la formation des stagiaires 32 Partie 4 Les colloques et journées d’étude 32 L’EPMO, Un établissement tête de réseau : l’EPMO en région 33 un rayonnement croissant 71 Les expositions en région 33 Les partenariats privilégiés 34 Un rayonnement mondial 73 Orsay Grand Département 34 Les expositions -

P22 445 Index

INDEXRUNNING HEAD VERSO PAGES 445 Explanatory or more relevant references (where there are many) are given in bold. Dates are given for all artists and architects. Numbers in italics are picture references. A Aurleder, John (b. 1948) 345 Aalto, Alvar (1898–1976) 273 Automobile Club 212 Abadie, Paul (1812–84) 256 Avenues Abaquesne, Masséot 417 Av. des Champs-Elysées 212 Abbate, Nicolo dell’ (c. 1510–71) 147 Av. Daumesnil 310 Abélard, Pierre 10, 42, 327 Av. Foch 222 Absinthe Drinkers, The (Edgar Degas) 83 Av. Montaigne 222 Académie Française 73 Av. de l’Observatoire 96 Alexander III, Pope 25 Av. Victor-Hugo 222 Allée de Longchamp 357 Allée des Cygnes 135 B Alphand, Jean-Charles 223 Bacon, Francis (1909–92) 270 American Embassy 222 Ballu, Théodore (1817–85) 260 André, Albert (1869–1954) 413 Baltard, Victor (1805–74) 261, 263 Anguier, François (c. 1604–69) 98, Balzac, Honoré de 18, 117, 224, 327, 241, 302 350, 370; (statue ) 108 Anguier, Michel (1614–86) 98, 189 Banque de France 250 Anne of Austria, mother of Louis XIV Barrias, Louis-Ernest (1841–1905) 89, 98, 248 135, 215 Antoine, J.-D. (1771–75) 73 Barry, Mme du 17, 34, 386, 392, 393 Apollinaire, Guillaume (1880–1918) 92 Bartholdi, Auguste (1834–1904) 96, Aquarium du Trocadéro 419 108, 260 Arc de Triomphe 17, 220 Barye, Antoine-Louis (1795–1875) 189 Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel 194 Baselitz, Georg (b. 1938) 273 Arceuil, Aqueduct de 372 Bassin du Combat 320 Archipenko, Alexander (1887–1964) Bassin de la Villette 320 267 Bastien-Lepage, Jules (1848–84) 89, Arènes de Lutèce 60 284 Arlandes, François d’ 103, 351 Bastille 16, 307 Arman, Armand Fernandez Bateau-Lavoir 254 (1928–2005) 270 Batignolles 18, 83, 234 Arp, Hans (Jean: 1886–1966) 269, 341 Baudelaire, Charles 31, 40, 82, 90, 96, Arras, Jean d’ 412 108 Arsenal 308 Baudot, Anatole de (1834–1915) 254 Assemblée Nationale 91 Baudry, F. -

La Sylve Au Bord De L'ourcq, À La Ferté Milon

La Sylve au Bord de l’Ourcq, à la Ferté Milon Le lundi 28 mai 2001, les "dénicheurs" de la Sylve, Après avoir quitté les bords du canal, nous nous Maurice et Pierre, nous entraînaient pour une sommes dirigés vers le village de Silly-la-Poterie, promenade avec pique-nique, depuis la avons longé un étang tout à fait romantique mais Ferté-Milon, sur les bords du Canal de l'Ourcq, à probablement infesté de moustiques, avant de l'orée de la forêt domaniale de Retz (une bonne reprendre haleine sur la pelouse ombragée d'un vingtaine de participants). ravissant château privé du XVIIIème siècle. Nous pique-niquons au bord d'un pré, avec pour ligne Par cette chaude journée ensoleillée, ce sont de crête l'orée de la forêt de Retz, servant d'écrin 10kms que nous avons parcourus sur le chemin au château. Après une heure et demie de halte de halage bordé de très vieux ou de tout jeunes pour déjeuner, pendant lequel circulaient bons peupliers, dans lesquels il est toujours si agréable mots, petits rouges, petits noirs, gâteaux et d'entendre le vent chanter. Un colvert et ses petits chocolats, nous avons repris nos sacs à dos ont beaucoup ému les enfants que nous sommes devenus plus légers pour rejoindre La Ferté Milon restés ; plus loin un ragondin, pressé, nous ignora, (fortifications d'un seigneur Milon, au VIIIème avant que, de l'ombre, ne surgisse, suprême siècle). L'heure culturelle avait sonné ! ! ! élégance... un cygne noir. Chemin faisant, Jeannine nous citait le nom des herbes folles et des fleurs L'église Saint Nicolas, du XVème siècle offre de des champs. -

Promenade Dans Le Parc Monceau

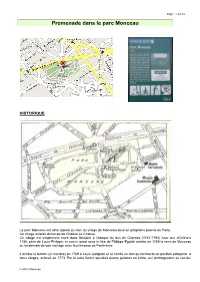

Page : 1 sur 16 Promenade dans le parc Monceau HISTORIQUE Le parc Monceau est ainsi appelé du nom du village de Monceau situé en périphérie proche de Paris. Ce village existait du temps de Charles Le Chauve. Ce village est simplement entré dans l’histoire à l’époque du duc de Chartres (1747-1793) futur duc d’Orléans 1785, père de Louis-Philippe, et connu aussi sous le titre de Philippe Egalité achète en 1769 la terre de Monceau au lendemain de son mariage avec la princesse de Penthièvre. Il achète le terrain (un hectare) en 1769 à Louis Colignon et lui confie en tant qu’architecte un pavillon octogonal, à deux étages, achevé en 1773. Par la suite furent ajoutées quatre galeries en étoile, qui prolongeaient au rez-de- Le Parc Monceau Page : 2 sur 16 chaussée quatre des pans, mais l'ensemble garda son unité. Colignon dessine aussi un jardin à la française c’est à dire arrangé de façon régulière et géométrique. Puis, entre 1773 et 1779, le prince décida d’en faire construire un autre plus vaste, dans le goût du jour, celui des jardins «anglo-chinois» qui se multipliaient à la fin du XVIIIe siècle dans la région parisienne notamment à Bagatelle, Ermenonville, au Désert de Retz, à Tivoli, et à Versailles. Le duc confie les plans à Louis Carrogis dit Carmontelle (1717-1806). Ce dernier ingénieur, topographe, écrivain, célèbre peintre et surtout portraitiste et organisateur de fêtes, décide d'aménager un jardin d'un genre nouveau, "réunissant en un seul Jardin tous les temps et tous les lieux ", un jardin pittoresque selon sa propre formule. -

Angkor Redux: Colonial Exhibitions in France

Angkor Redux: Colonial Exhibitions in France Dawn Rooney offers tantalising glimpses of late 19th-early 20th century exhibitions that brought the glory of Angkor to Europe. “I saw it first at the Paris Exhibition of 1931, a pavilion built of concrete treated to look like weathered stone. It was the outstanding feature of the exhibition, and at evening was flood-lit F or many, such as Claudia Parsons, awareness of the with yellow lighting which turned concrete to Angkorian kingdom and its monumental temples came gold (Fig. 1). I had then never heard of Angkor through the International Colonial Exhibitions held in Wat and thought this was just a flight of fancy, France in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a wonder palace built for the occasion, not a copy of a temple long existent in the jungle of when French colonial presence in the East was at a peak. French Indo-China. Much earlier, the Dutch had secured domination over Indonesia, the Spanish in the Philippines, and the British But within I found photographs and read in India and Burma. France, though, did not become a descriptions that introduced me to the real colonial power in Southeast Asia until the last half of the Angkor and that nest of temples buried with it nineteenth century when it obtained suzerainty over Cam- in the jungle. I became familiar with the reliefs bodia, Vietnam (Cochin China, Tonkin, Annam) and, lastly, and carved motifs that decorated its walls, Laos. Thus, the name ‘French Indochina’ was coined not and that day I formed a vow: Some day . -

Atlas 1860 Des Chemins De Fer Français

ATLAS HISTORIQUE ET STATISTIQUE DES PAR ADOLPHE JOANNE Auteur des Itinéraires de la Suisse, de l'Allemagne; des Pyrénées des Environs de Paris, etc. CONTENANT 8 CARTES GRAVÉES SUR ACIER PARIS LIBRAIRIE DE L. HACHETTE ET Gic RUÈ PIERRE -SARRAZIN, N° 14 ( Près de l'École de médecine ) 1859 TABLE DES MATIÈRES. PRÉFACE. Page Exploitation de l'année 1857. Page 63 Etat des 69 INTRODUCTION 1 travaux. Conseil d'administration 71 Résumé historique. 2 Organisationadministrative et financière. 9 Le chemin de fer de Lyon à Genève. 72 Les compagnies. 11 Le réseau 72 Établissement. 12 Situation financièreen 73 Exploitation. 15 Exploitationdes années 1856 et 1857. 74 Tableau chronologiquedes ouvertures de lignes et Etat des travaux. sections. 18 Conseil d'administration. 76 Les chemins de fer du Nord. 21 Les chemins de fer du Midi et le canal latéral à Le 21 la 77 Situationréseau.financière en 1857. 22 Le Exploitation de l'année 24 Situationréseau.financièreen 79 27 1857. Etat des travaux. Exploitation de l'année 1857 Conseil d'administration 29 Etat des 85 30 travaux. Les chemins de fer de l'Est Conseil d'administration 86 Le 30 Les chemins de fer du Situationréseau. financière en 1857. 31 Le chemin de fer de 91. Exploitation de l'année 32 Ceinture. 1857. Le chemin de fer de Bessègesà Alais Etat destravaux. 33 93 Conseil d'administration. 35 Le chemin de fer de Graissessac à 94 :Les chemins de fer des 36 Le chemin de fer de Bordeaux au 94 Le 36 Les chemins de fer industriels 95. Exploitationréseau.de l'année 36 95 Situation financière en 37 De Cramaux à 95 37 Du chemin de CeintureAlby.à la de gare 95 Conseil d'administration 38 D'Hautmont à la frontière belge. -

Jean-Charles-Adolphe Alphand Et Le Rayonnement Des Parcs Publics De L’École Française E Du XIX Siècle

Jean-Charles-Adolphe Alphand et le rayonnement des parcs publics de l’école française e du XIX siècle Journée d’étude organisée dans le cadre du bi-centenaire de la naissance de Jean-Charles-Adolphe Alphand par la Direction générale des patrimoines et l’École Du Breuil 22 mars 2017 ISSN : 1967-368X SOMMAIRE Introduction et présentation p. 4 Carine Bernède, directice des espaces verts et de l’environnement de la Ville de Paris « De la science et de l’Art du paysage urbain » dans Les Promenades de Paris (1867-1873), traité de l’art des jardins publics p. 5 Chiara Santini, docteur en histoire (EHESS-Université de Bologne), ingénieur de recherche à l’École nationale supérieure de paysage de Versailles-Marseille Jean-Pierre Barillet-Deschamps, père fondateur d’une nouvelle « école paysagère » p. 13 Luisa Limido, architecte et journaliste, docteur en géographie Édouard André et la diffusion du modèle parisien p. 19 Stéphanie de Courtois, historienne des jardins, enseignante à l’École nationale supérieure d’architecture de Versailles Les Buttes-Chaumont : un parc d’ingénieurs inspirés p. 27 Isabelle Levêque, historienne des jardins et paysagiste Les plantes exotiques des parcs publics du XIXe siècle : enjeux et production aujourd’hui p. 36 Yves-Marie Allain, ingénieur horticole et paysagiste DPLG Le parc de la Tête d’Or à Lyon : 150 ans d’histoire et une gestion adaptée aux attentes des publics actuels p. 43 Daniel Boulens, directeur des Espaces Verts, Ville de Lyon ANNEXES Bibliographie p. 51 -2- Programme de la journée d’étude p. 57 Présentation des intervenants p. -

Château De La Muette 2, Rue André Pascal Paris 75016 28 -30 June 2004

OECD SHORT-TERM ECONOMIC STATISTICS EXPERT GROUP MEETING (STESEG) Château de la Muette 2, rue André Pascal Paris 75016 28 -30 June 2004 INFORMATION General 1. The Short-term Economic Statistics Expert Group (STESEG) meeting is scheduled to be held at the OECD headquarters at 2, rue André Pascal, Paris 75016, from Monday 28 June to Wednesday 30 June 2004. 2. The meeting will commence at 9.30am on Monday 28 June 2004 and will be held in Room 2 for the first two days and Room 6 on the third day. Registration and identification badges 3. All delegates are requested to register with the OECD Security Section and to obtain ID badges at the Reception Centre, located at 2, rue André Pascal, on the first morning of the meeting. It is advisable to arrive there no later than 9.00am; queues often build up just prior to 9.30am because of the number of meetings which start at that time. Please note you should bring some form of photo identification with you. 4. For identification and security reasons, participants are requested to wear their security badges at all times while inside the OECD complex. Immigration requirements 5. Delegates travelling on European Union member country passports do not require visas to enter France. All other participants should check with the relevant French diplomatic or consular mission on visa requirements. If a visa is required, it is your responsibility to obtain it before travelling to France. If you need a formal invitation to support your visa application please contact the Statistics Directorate well before the meeting. -

Vysoké Učení Technické V Brně Brno University of Technology

VYSOKÉ UČENÍ TECHNICKÉ V BRNĚ BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY FAKULTA STAVEBNÍ FACULTY OF CIVIL ENGINEERING ÚSTAV TECHNOLOGIE STAVEBNÍCH HMOT A DÍLCŮ INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OF BUILDING MATERIALS AND COMPONENTS VLIV VLASTNOSTÍ VSTUPNÍCH MATERIÁLŮ NA KVALITU ARCHITEKTONICKÝCH BETONŮ INFLUENCE OF INPUT MATERIALS FOR QUALITY ARCHITECTURAL CONCRETE DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE DIPLOMA THESIS AUTOR PRÁCE Bc. Veronika Ondryášová AUTHOR VEDOUCÍ PRÁCE prof. Ing. RUDOLF HELA, CSc. SUPERVISOR BRNO 2018 1 2 3 Abstrakt Diplomová práce se zaměřuje na problematiku vlivu vlastností vstupních surovin pro výrobu kvalitních povrchů architektonických betonů. V úvodní části je popsána definice architektonického betonu a také výhody a nevýhody jeho realizace. V dalších kapitolách jsou uvedeny charakteristiky, dávkování či chemické složení vstupních materiálů. Kromě návrhu receptury je důležitým parametrem pro vytvoření kvalitního povrchu betonu zhutňování, precizní uložení do bednění a následné ošetřování povrchu. Popsány jsou také jednotlivé druhy architektonických betonů, jejich způsob vyrábění s uvedenými příklady na konkrétních realizovaných stavbách. V praktické části byly navrženy 4 receptury, kde se měnil druh nebo dávkování vstupních surovin. Při tvorbě receptur byl důraz kladen především na minimální segregaci čerstvého betonu a omezení vzniku pórů na povrchu ztvrdlého betonu. Klíčová slova Architektonický beton, vstupní suroviny, bednění, separační prostředky, cement, přísady, pigment. Abstract This diploma thesis focuses on the influence of properties of feedstocks for the production of quality surfaces of architectural concrete. The introductory part describes the definition of architectural concrete with the advantages and disadvantages of its implementation. In the following chapters, the characteristics, the dosage or the chemical composition of the input materials are given. Besides the design of the mixture, important parameters for the creation of a quality surface of concrete are compaction, precise placement in formwork and subsequent treatment of the surface. -

Vieux Bourg De La Ferté-Milon

LA FERTE-MILON 02-07 Vieux bourg de la Ferté-Milon Ruines du château Eglise Notre-Dame Place du vieux château SITE INSCRIT Vers Villers-Coterêts Arrêté du 2 février 1965. CRITÈRE : Pittoresque, Historique YPOLOGIE T : Vers Paris Site urbain, bourg, village Canal de l’Ourcq MOTIVATION DE PROTECTION Rapport de présentation absent Le site du vieux bourg couvre une entité bâtie homogène au caractère historique très marqué. Le périmètre s’étend à l’église, au château, aux places et aux rues ainsi qu’aux façades et toitures des constructions qui parti- cipent à l’ambiance convi- viale et pittoresque de la ville. « La Ferté-Milon se compose de deux rues, l’une la Chaussée, va de colline à colline à travers 19 DÉLIMITATION-SUPERficiE AISNE 8,55 hectares. la vallée en franchissant l’Ourcq ; l’autre longe le pied du coteau taillé en falaise sur lequel Louis d’Orléans voulut édifier son palais fortifié. (...) Cette église fut le noyau de la Cité ; tout PROPRIÉTÉ PUBLIQUE autour dévalent des rues irrégulières bordées de vieilles bâtisses et pauvrement habitées, ET PRIVÉE. aboutissant à une terrasse qui porte les ruines du château ou plutôt l’une de ses façades, car AUTRES PROTECTIONS : le puissant palais garde une seule paroi, flanquée de quatre tours dont deux encadrent la porte . Site inclus dans la ZPPAUP (...). Cette façade monumentale regarde la campagne et non la bourgade ; du côté de celle-ci de la Ferté-Milon (04 mars il n’y a qu’un mur cyclopéen formant terrasse et qui, sans doute, ne fut jamais élevé plus haut.