Yellow Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telecommunication Switching Networks

TELECOMMUNICATION SWITCHING AND NETWORKS TElECOMMUNICATION SWITCHING AND NffiWRKS THIS PAGE IS BLANK Copyright © 2006, 2005 New Age International (P) Ltd., Publishers Published by New Age International (P) Ltd., Publishers All rights reserved. No part of this ebook may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microfilm, xerography, or any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the publisher. All inquiries should be emailed to [email protected] ISBN (10) : 81-224-2349-3 ISBN (13) : 978-81-224-2349-5 PUBLISHING FOR ONE WORLD NEW AGE INTERNATIONAL (P) LIMITED, PUBLISHERS 4835/24, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi - 110002 Visit us at www.newagepublishers.com PREFACE This text, ‘Telecommunication Switching and Networks’ is intended to serve as a one- semester text for undergraduate course of Information Technology, Electronics and Communi- cation Engineering, and Telecommunication Engineering. This book provides in depth knowl- edge on telecommunication switching and good background for advanced studies in communi- cation networks. The entire subject is dealt with conceptual treatment and the analytical or mathematical approach is made only to some extent. For best understanding, more diagrams (202) and tables (35) are introduced wherever necessary in each chapter. The telecommunication switching is the fast growing field and enormous research and development are undertaken by various organizations and firms. The communication networks have unlimited research potentials. Both telecommunication switching and communication networks develop new techniques and technologies everyday. This book provides complete fun- damentals of all the topics it has focused. However, a candidate pursuing postgraduate course, doing research in these areas and the employees of telecom organizations should be in constant touch with latest technologies. -

Media Technology and Society

MEDIA TECHNOLOGY AND SOCIETY Media Technology and Society offers a comprehensive account of the history of communications technologies, from the telegraph to the Internet. Winston argues that the development of new media, from the telephone to computers, satellite, camcorders and CD-ROM, is the product of a constant play-off between social necessity and suppression: the unwritten ‘law’ by which new technologies are introduced into society. Winston’s fascinating account challenges the concept of a ‘revolution’ in communications technology by highlighting the long histories of such developments. The fax was introduced in 1847. The idea of television was patented in 1884. Digitalisation was demonstrated in 1938. Even the concept of the ‘web’ dates back to 1945. Winston examines why some prototypes are abandoned, and why many ‘inventions’ are created simultaneously by innovators unaware of each other’s existence, and shows how new industries develop around these inventions, providing media products for a mass audience. Challenging the popular myth of a present-day ‘Information Revolution’, Media Technology and Society is essential reading for anyone interested in the social impact of technological change. Brian Winston is Head of the School of Communication, Design and Media at the University of Westminster. He has been Dean of the College of Communications at the Pennsylvania State University, Chair of Cinema Studies at New York University and Founding Research Director of the Glasgow University Media Group. His books include Claiming the Real (1995). As a television professional, he has worked on World in Action and has an Emmy for documentary script-writing. MEDIA TECHNOLOGY AND SOCIETY A HISTORY: FROM THE TELEGRAPH TO THE INTERNET BrianWinston London and New York First published 1998 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. -

Association Des Amis Des Cables Sous-Marins Bulletin N° 51

ASSOCIATION DES AMIS DES CABLES SOUS-MARINS Le NC Antonio MEUCCI à La Seyne en août 2014 (G Fouchard) BULLETIN N° 51 – FEVRIER 2016 1 SOMMAIRE NUMERO 51 – FEVRIER 2016 Articles Auteurs Pages Couverture : Le NC Meucci à La Seyne sur Mer Rédaction 1 Sommaire Rédaction 2 Le billet du Président A. Van Oudheusden 3 La lettre du trésorier Gérard Fouchard 4 Undersea Fiber Communication Systems José Chesnoy 5 Le NC Meucci et les mensonges de l’histoire Rédaction 6 La technologie du futur des câbles sous marins José Chesnoy 10 L’actualité des câbles sous-marins Loic Le Fur 20 Les sémaphores de la Marine Yves Lecouturier 23 Gustave Ferrié et la radio pendant la Grande Guerre Gérard Fouchard 31 Paul Langevin à Toulon pendant la grande guerre Gérard Fouchard 39 Le point de vue de Pierre Suard Pierre Suard 45 Hommage à Alain Bacquey Jocelyne Yépès 46 Hommage à Marcel Ferrara J. L Bricout 47 Hommage à Jean Le Tiec Christian Delanis 48 Hommage à René Salvador Gérard Fouchard 49 FIN DE VOTRE ABONNEMENT AU BULLETIN Le numéro 50 devait être le dernier bulletin mais l’actualité, la technologie et les témoignages sur la guerre de 1914-1918 permettent l’édition plusieurs bulletins complémentaires. La trésorerie de l’association le permet. Je vous rappelle que la cotisation annuelle est de 5 euros. Seule une adhésion à jour vous permet recevoir le bulletin. Gérard Fouchard - Trésorier de l’AACSM - 40 Quai Hoche -83500 LA SEYNE SUR MER Site de l’association : www. Cablesm.fr 2 LE BILLET DU PRESIDENT Alain Van Oudheusden Je tiens à présenter à tous les adhérents, au nom du Bureau, mes meilleurs vœux à l’aube de 2016 et ce nouveau bulletin. -

A Compact Telecommunication System for Apartment

ISSN 2321 3361 © 2019 IJESC Research Article Volume 9 Issue No.9 A Compact Telecommunication System for Apartment Chandam Thoisana Singh BE Student Department of Electronics & Communication Engineering Manipur Institute of Technology, Manipur, India Abstract: This paper presents a multifunction and a multi-useful device that can be widely applicable and can be easily installed and handled by an ordinary person. In this paper the system i.e. A Compact Telecommunication System for Apartment is used as an EPABX (Electronic Private Automatic Branch Exchange) which maintains the privacy. Keywords: EPABX, Opto-isolation, Timer, Relay, Tone decoder, BCD to ten line decoder, Switches, IVRS. I. INTRODUCTION: They set the rates the phone companies could charge and determined that services and equipment each could offer. This As with many innovations, the idea for the telephone came stayed in effect until AT&T’s forced divestiture in 1984, the along far sooner than it was brought to reality. While Italian conclusion of a U.S. Department of Justice anti-trust suit that innovator Antonia Meucci is credited with inventing the first had been filed in 1974. The all powerful company had become basic phone in 1849, and Frenchman Charles Bourseul devised popularly known and disparaged as “Ma Bell.” AT&T’s local a phone in 1854, Alexander Graham Bell won the first U.S operations were divided into seven independent Regional Bell patent for the device in 1876. Bell began his research in 1874 Operating Companies, known as the “Baby Bells.” AT&T and had financial backers who gave him the best business plan became a long-distance-services company. -

Telephone – Inventions That Revolutionized the World

Telephone – Inventions that Revolutionized the World December 14, 2018 First Publication Date: 27th November 2010 The most common devices used for transmitting the voice signal over a greater distance are pipes and other physical mechanical media. All of us as a child must have used this form for communication. Another device used for centuries for voice communication is lover’s phone or tin can telephone. The classic example is the children’s toy made by connecting the bottoms of two paper cups, metal cans, or plastic bottles with string. But the invention which changed the entire scenario of the communication is the telephone. It revolutionized the entire communication system. People could hear the voice of their loved ones staying miles away. Telephone comes from the Greek word tele, meaning from afar, and phone, meaning voice or voiced sound. Generally, a telephone is any device which conveys sound over a distance During the second half of the 19th century many well-known inventors were trying to develop an acoustic telegraphy for economic telegraph messages which included Charles Bourseul, Thomas Edison, Antonio Meucci, Johann Philipp Reis, Elisha Gray, and Alexander Graham Bell. The ‘speaking telegraph’ or in simple terms ‘telephone’ emerged from the creation and gradual improvement of telegraph. The invention of telephone has been one of the most disputed facts of all time. Credit for the invention of the electric telephone is never an ending dispute and new controversies over the issue keeps arising from time-to-time. The Elisha Gray and Alexander Bell controversy raises the question of whether Bell and Gray invented the telephone independently and, if that’s not true, then whether Bell stole the invention from Gray. -

March of Mobile Money: the Future of Lifestyle Management

The March of Mobile Money THE FUTURE OF LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT SAM PITRODA & MEHUL DESAI The March of Mobile Money THE FUTURE OF LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT SAM PITRODA & MEHUL DESAI First published in India in 2010 by Collins Business An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers a joint venture with The India Today Group Copyright © Sam Pitroda and Mehul Desai 2010 ISBN: 978-81-7223-865-0 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 Sam Pitroda and Mehul Desai assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. HarperCollins Publishers A-53, Sector 57, Noida 201301, India 77-85 Fulham Palace Road, London W6 8JB, United Kingdom Hazelton Lanes, 55 Avenue Road, Suite 2900, Toronto, Ontario M5R 3L2 and 1995 Markham Road, Scarborough, Ontario M1B 5M8, Canada 25 Ryde Road, Pymble, Sydney, NSW 2073, Australia 31 View Road, Glenfield, Auckland 10, New Zealand 10 East 53rd Street, New York NY 10022, USA Typeset in 12/18.3 Dante MT Std InoSoft Systems Printed and bound at Thomson Press (India) Ltd We would like to thank the entire C-SAM family and its well-wishers, without whom this journey would not be as enriching. We would like to thank Mayank Chhaya, without whom we would not have been able to complete this book. We would like to thank our better halves, Anu and Malavika, without whose companionship this journey and book would not be as meaningful. -

THE BELL SYSTEM TECHNICAL JOURNAL Volume Xxxvii March

THE BELL SYSTEM TECHNICAL JOURNAL volume xxxvii March 1958 number2 Copyright 195S, American Telephone and Telegraph Company Telephone By E. T. GREEN This article, which appeared in the 1957 printing of the Encyclopedia Brilannica* has been reprinted by special permission for readers of the Bell System Technical Journal. All statistics have been corrected to the latest available figures. An objective account of the invention of the telephone itself is given, and the subsequent development and growth of telephony are described. A statisti- cal summary is presented of the intensity of development in different parts of the world. This is followed by a comprehensive review of technical develop- nients, including progress in station instrumentalities, and transmission and switching principles and methods. The article concludes with a predic- tion of trends to he anticipated in telephony as a result of recent technical advances. The term 'Telephone" (from the Greek roots rfjXe, far, and (puvh, sound) was formerly used to describe any apparatus for conveying sounds to a distant point. Specifically, the word was applied as early as 1796 to a megaphone, and not long afterward to a speaking tube. Subse- quently the name "string telephone" was given to the device invented long before by Robert Hooke (1607), in which vibrations in a diaphragm caused by voice or sound waves are transmitted mechanically along a string or wire to a similar diaphragm which reproduces the sound. Still later, devices employing electric currents to reproduce at a distance the mere pitch of musical sounds were called telephones. Nowadays, how- ever, this name is assigned almost exclusively to apparatus for reproduc- * Copyright 1957 by Encyclopedia Britaonica 2S9 290 THE BELL SYSTEM TECHNICAL JOURNAL, MARCH 1958 ing articulate speech and other sounds at a distance through the medium, of electric waves. -

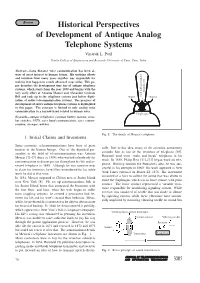

Historical Perspectives of Development of Antique Analog Telephone Systems Vinayak L

Review Historical Perspectives of Development of Antique Analog Telephone Systems Vinayak L. Patil Trinity College of Engineering and Research, University of Pune, Pune, India Abstract—Long distance voice communication has been al- ways of great interest to human beings. His untiring efforts and intuition from many years together was responsible for making it to happen to a such advanced stage today. This pa- per describes the development time line of antique telephone systems, which starts from the year 1854 and begins with the very early effort of Antonio Meucci and Alexander Graham magnet core Bell and ends up to the telephone systems just before digiti- Wire 1Coil with permanent Wire 2 zation of entire telecommunication systems. The progress of development of entire antique telephone systems is highlighted in this paper. The coverage is limited to only analog voice communication in a narrow band related to human voice. Diaphragm Keywords—antique telephones, common battery systems, cross- bar switches, PSTN, voice band communication, voice commu- nication, strowger switches. Fig. 1. The details of Meucci’s telephone. 1. Initial Claims and Inventions Since centuries, telecommunications have been of great cally. Due to this idea, many of the scientific community interest to the human beings. One of the dignified per- consider him as one of the inventors of telephone [10]. sonality in the field of telecommunication was Antonio Boursuel used term “make and break” telephone in his Meucci [1]–[7] (born in 1808) who worked relentlessly for work. In 1850, Philip Reis [11]–[13] began work on tele- communication to distant person throughout his life and in- phone. -

The Telephone a Revolution in Communication

UNIVERSITATEA TRANSILVANIA DIN BRASOV The telephone A revolution in communication Student: Teris Alexandra IEC 4521 Coordinating teacher: Prof. Dr. Ing. Helerea Elena Teris Alexandra IEC 4521 May 2013 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..........................................................................................................3 2. Description and operating principle ..................................................................3 3. History of the device .......................................................................................4 3.1 Evolution of the device ...............................................................................5 3.2 The telephone in Romania ........................................................................6 4. Impact on the society ......................................................................................7 5. Conclusions .....................................................................................................7 6. Bibliography .....................................................................................................7 7. Iconography .....................................................................................................7 2 Teris Alexandra IEC 4521 1. Introduction In our days we run along an “information superhighway” with sophisticated utensils which are far away of the first telephone. Such communication devices like computers, mobile telephones, pagers, caller ID, call waiting, numbers like 112, are now taken for granted. Modern electronic -

Judicial Developments and Legislative Proposals*

PATENTS: JUDICIAL DEVELOPMENTS AND LEGISLATIVE PROPOSALS* SYLVESTER PETROt THERE are some things about the patent system that can never be known as fully and directly as one might desire, e.g., whether or not it has operated on the whole to retard technological devel- opment in the United States. On the other hand, there are many impor- tant things about the patent system that can be and are known. The system has been in operation for over 15o years, and in that time it has produced, as a glance at the digest of federal cases will show, more litiga- tion than any other subject of federal jurisdiction except taxation and bankruptcy. From an examination of some of this litigation and consider- ation of the nature of science, technology, and invention, it appears that the subject matter is such as to make a fair decision in any vigorously dis- puted case concerning priority, validity, or scope of invention extremely difficult, if not impossible. This is true, in brief, because in an extremely signi cant sense, there is seldom an invention or a single inventor. In its attempt to grant rewards to single inventors for single inventions, there- fore, the patent system seems to have essayed the impossible. And from this attempt a multitude of evils have resulted. One can also know that the patent system has been one of the principal factors in the growth of private monopoly power in the United States. For this there is sufficient proof in the reported cases and in the facts that have come to light in recent years. -

Newsletter March/April

COURAGE, STRENGTH AND DETERMINATION 2015 Newsletter March/April International School of the Algarve’s students achieved excellent results at the Mega Sprinter – Athletics Event Students of the International School of the Algarve recently participated in the Athletic Festival held in Está- dio Municipal da Belavista, in the village of Parchal, and achieved excellent results: Under 10 Girls 3rd place Vortex Throw - Inês Dias Under 10 Boys 1st place Vortex Throw – Regional Champion Ricardo Ribeiro Under 12 Girls 1st Place Mega Sprinter – Regional Champion Carolina de Lagos 3rd place Vortex Throw Diana Lemeshko Under 16 Girls 3rd Mega Sprinter Building a “tin can” phone Yelyzaveta Lemeshko The “8ºano” science class built ‘tin can’ phones using 2nd place Mega KM plastic cups and strings. This old toy simulates the Runner- up – Madalena Severino operation of telephone equipment and allows 2nd place Mega Jump – Runner – up students to understand that sound is a vibration. It Catarina Duarte was a fun way to comprehend the different properties Solar eclipse on the last day of School of sound. A total solar eclipse was visible on Friday the The phone, a device designed to transform and emit 20th of March 2015 as a partial eclipse sound waves into electrical impulses as well as receive throughout Portugal. The total eclipse was only these signals, converting electrical signals into sound. visible in the far north Atlantic, the Faroe This is transmitted by wire cables and more recently by Islands, Svalbard and the Arctic region (through optical fiber. There is some controversy over the name the North Pole), an area between 410 and 480 of the telephone’s inventor, commonly idefined as km. -

Telecomwriting.Com's Telephone History Series

privateline.com's Telephone History Series by Tom Farley 215 19th Street West Sacramento, California 95691 USA http://www.privateline.com http://www.privateline.tv [email protected] [email protected] Compilation and .pdf formatting by Dave Mock http://www.geocities.com/dmock_1/ [email protected] Privateline.com's Telephone History Series by Tom Farley http://www.privateline.com Private Line's Telephone History Part 1 -- to 1830 "We picture inventors as heroes with the Intrigue aside for now, the story of the genius to recognize and solve a society's telephone is the story of invention itself. problems. In reality, the greatest inventors have been tinkerers who loved tinkering for its Bell developed new and original ideas but own sake and who then had to figure out what, did so by building on older ideas and if anything, their devices might be good for." developments. Bell succeeded specifically Jared Diamond because he understood acoustics, the study of sound, and something about electricity. I. Introduction II. Early Telephone Development III. The Other inventors knew electricity well but Inventors: Gray and Bell little of acoustics. The telephone is a shared accomplishment among many pioneers, therefore, although the credit and I. Introduction rewards were not shared equally. That, too, is often the story of invention. Telephone comes from the Greek word " . an inspired black- haired Scotsman of tele, meaning from afar, and phone, twenty eight, on the meaning voice or voiced sound. Generally, eve of marriage, a telephone is any device which conveys vibrant and alive to sound over a distance. A string telephone, new ideas." Alexander a megaphone, or a speaking tube might be Graham Bell : The Life and Times of the Man considered telephonic instruments but for Who Invented the our purposes they are not telephones.