The Changing Role of Official Donors in Humanitarian Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nominations Committee

36TH SESSION - UNESCO GENERAL CONFERENCE INFORMATION OFFICE ORGAN NOMINATIONS COMMITTEE Date 25 October 2011 Room Room IV From: 12:00 a.m. No meeting First meeting Hour To: 1:30 p.m. Chairperson(s) Mr David Hamadziripi Country Zimbabwe SUMMARY OF DEBATE(S) Items examined 1.5: Election of the President and Vice-Presidents of the General Conference and of the Chairpersons, Vice-Chairpersons and Rapporteurs of the commissions and committees Debate status Start Related documents 36 C/NOM/8 Prov.; 36 C/NOM/1; 36 C/NOM/1 Add. DRs examined N/A Countries that took Azerbaijan, Ecuador, Egypt, India and Philippines floor Summary of debate 1. The Vice-Chairperson of the Executive Board, Mr Isao Kiso (Japan), opened the first meeting of the Nominations Committee and on the recommendation of the Executive Board, contained in decision 186 EX/Decision 22(IV), the Committee elected as its Chairperson Mr David Hamadziripi (Zimbabwe). 2. The Nominations Committee approved the recommendation of the Executive Board contained in decision 187 EX/Decision 26(v) to elect Madame Katalin Bogyay (Hungary) as President of the 36th session of the General Conference. 3. On recommendation of the Executive Board at its 187th session, the Committee nominated the heads of delegations of 36 Member States for the posts of Vice-Presidents of the 36th session of the General Conference. These Member States are as follows: Albania, Australia, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Croatia, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Denmark, Egypt, El Salvador, France, Germany, Grenada, Kenya, Kuwait, Lao People’s Democratic, Republic, Latvia,Lebanon, Madagascar, Montenegro, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Saint Lucia, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Serbia, Thailand, United States of America, Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), Yemen and Zambia. -

The Burundi Peace Process

ISS MONOGRAPH 171 ISS Head Offi ce Block D, Brooklyn Court 361 Veale Street New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 346-9570 E-mail: [email protected] Th e Burundi ISS Addis Ababa Offi ce 1st Floor, Ki-Ab Building Alexander Pushkin Street PEACE CONDITIONAL TO CIVIL WAR FROM PROCESS: THE BURUNDI PEACE Peace Process Pushkin Square, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Th is monograph focuses on the role peacekeeping Tel: +251 11 372-1154/5/6 Fax: +251 11 372-5954 missions played in the Burundi peace process and E-mail: [email protected] From civil war to conditional peace in ensuring that agreements signed by parties to ISS Cape Town Offi ce the confl ict were adhered to and implemented. 2nd Floor, Armoury Building, Buchanan Square An AU peace mission followed by a UN 160 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock, South Africa Tel: +27 21 461-7211 Fax: +27 21 461-7213 mission replaced the initial SA Protection Force. E-mail: [email protected] Because of the non-completion of the peace ISS Nairobi Offi ce process and the return of the PALIPEHUTU- Braeside Gardens, Off Muthangari Road FNL to Burundi, the UN Security Council Lavington, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 386-1625 Fax: +254 20 386-1639 approved the redeployment of an AU mission to E-mail: [email protected] oversee the completion of the demobilisation of ISS Pretoria Offi ce these rebel forces by December 2008. Block C, Brooklyn Court C On 18 April 2009, at a ceremony to mark the 361 Veale Street ON beginning of the demobilisation of thousands New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa DI Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 460-0998 TI of PALIPEHUTU-FNL combatants, Agathon E-mail: [email protected] ON Rwasa, leader of PALIPEHUTU-FNL, gave up AL www.issafrica.org P his AK-47 and military uniform. -

Africa Two Views on the Crisis in Sudan

programAfrica two views on the crisis in sudan Nureldin Satti, UNESCO (Ret) August 2010 John Prendergast and Laura Jones, Enough Project Introduction by Steve McDonald and Alan Goulty, Woodrow Wilson Center Working Group Series Paper No. 1 Based on the Expert Policy Working Group on Sudan of the Africa Program Working Group Series Paper No. 1 SUdan at A CROSSROADS UPDATE: During the first week of August, at a high level U.S. Government meeting on Sudan, tensions erupted be- tween senior administration officials over disagreements on the issues of Darfur, management of the referendum, and incentives and pressures on the Bashir government, which are the focus of this report. Foreign Policy Magazines Blog, the Cable, written by Josh Rogin, reported the clash on August 13, 2010, saying a memo had been sent forward to President Obama for determination, but the end result could be the reassignment of Special Envoy Scott Gration. The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, not been publicly shared, have served an invaluable pur- under its Africa Program and Project for Leadership and pose of linking voices and interests not always in contact Building State Capacity, has been, with the support of the with one another, and in spinning off public elements, Open Society Institute, conducting an such as the conference on Sudan on-going effort to engage and inform held on June 14, 2010, with for- policy makers on issues important to mer South African President Thabo U.S. national interests. This takes the Mbeki and UN Special Representa- form of open public conferences or tive of the Secretary General, Haile presentations, closed policy working Menkerios, when they spoke on UN groups, and occasional publications. -

WIFI: BL-GUEST-CONF PW:Blgue5t23 #Acbooksouth Delegate List

The Academic Book in the South Programme at a Glance DAY 1: Monday 7th March 2016 10.00 Welcome - Caroline Brazier, Chief Librarian, The British Library 10.05 Introduction - Maja Maricevic (British Library), Marilyn Deegan (King’s College) anD Caroline Davis (OxforD Brookes University) 10.15 Academic Authorship and Knowledge Production: Chair, Marilyn Deegan Sukanta ChauDhuri, Jadavpur University 11.00 Sari Hanafi, American University of Beirut 11.45 Coffee 12.15 Panel Discussion Stephanie Kitchen, Managing EDitor, International Africa Institute anD Managing EDitor, Africa Insa Nolte, Department of African StuDies anD Anthropology, University of Birmingham Padmini Ray Murray, Srishti Institute of Art, Design anD Technology Ola Uduku, Reader in Architecture anD Dean International for Africa, University of Edinburgh 1.15 Lunch 2.15 Academic Publishing in the South: Chair, Caroline Davis Walter Bgoya, Mkuki na Nyota Publishers, Tanzania 3.00 Akoss Ofori-Mensah, Sub-Saharan Publishers, Ghana 3.45 Tea 4.15 Panel Discussion Frances Pinter, KnowleDge UnlatcheD Mary Jay, African Books Collective Lynn Taylor, Managing EDitor, Boydell anD Brewer /James Currey Maria Marsh, CambriDge University Press 5.30 Close & Drinks Reception DAY 2: Tuesday 8th March 10.00 Welcome anD IntroDuction to Day 2 10.10 The Role of Libraries and Archives: Chair, Maja Maricevic NurelDin M. Satti, National Library of SuDan & SuDanese Association for the Archiving of Knowledge 11.00 Shamil Jeppie, Timbuktu Project, University of Cape Town 11.45 Coffee 12.15 Panel Discussion -

Welcome to the United Nations Office in Burundi(ONUB)-Press

Welcome to the United Nations Office in Burundi (UNOB) °°°°°°°°°°°°° PRESS KIT °°°°°°°°°°°°° Public Information Office BUJUMBURA FEBRUARY 2004 UNOB PRESS KIT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page number Map of Burundi………………………………………………………………………... 2 I. UNOB’s Mandate and the Mechanisms for its Implementation UNOB in Brief………………………………………………………...……………. 3 The Arusha Agreement……………………………………………………………... 4 The Implementation Monitoring Committee (IMC)………………………………... 5 The Joint Ceasefire Commission (JCC)……………………………………….……. 6 II. Burundi: The Political Setting Recent Political Events and Outlook for 2004……………………………………... 7 Chronology of Recent Events…………………………………………………….... 8 Profile of Government……………………………………………………………... 9 Members of the Transitional Government 10 List of Political Parties and Armed Movements ………………………………….. 11-12 III. Biographies Berhanu Dinka, Special Representative of the Secretary-General…..…………….. 13 Nureldin Satti, Deputy to the Special Representative of the Secretary- General.…………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Ayite J.C. Kpakpo, Director, IMC Secretariat ..…………………………………... 15 Brigadier General El Hadji Alioune Samba, Chairman, JCC……………………… 16 Annex I: African Mission in Burundi……………………………………….…. … 17 Annex II: Key Indicators for Burundi……………………………………………… 18 MAP OF BURUNDI __________________________________________________________________________________________ 15feb04 UNOB PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE 3 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE IN BURUNDI (UNOB) v UNOB's establishment and evolution: UNOB was established on 25 October 1993 at the request -

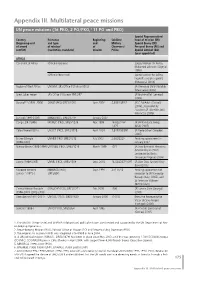

Appendix III. Multilateral Peace Missions

Appendix III. Multilateral peace missions UN peace missions (16 PKO, 2 PO/PKO,1 11 PO and PBO) Special Representative/ Country Existence Beginning- Soldiers/ head of mission (SR) (beginning-end and type end Military Special Envoy (SE) of armed of mission2 of Observers/ Personal Envoy (PE) and conflict) (resolution, mandate) mission Police Special Adviser (SA) (year appointed) AFRICA Continent of Africa (Office in Geneva) Special Adviser for Africa, Mohamed Sahnoun (Algeria) (1997) (Office in New York) Special Adviser for Africa, Legwaila Joseph Legwaila (Botswana) (2006) Region of West Africa UNOWA, SR’s Office (PO) since 03/02 SR Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah (Mauritania) (2002) Great Lakes region SR’s Office (PO) since 19/12/97 SR Ibrahima Fall (Senegal) (2002) Burundi** (1993- 2006) ONUB3 (PKO) S/RES/1545 June 2004 5,336/189/87 SR C. McAskie (Canada) (2004), succeeded by Assistant SR, Nureldin Satti (Morocco) (2006) Burundi (1993-2006) BINUB (PBO), S/RES/1719 January 2007 Congo, DR (1998-) MONUC (PKO), S/RES/1279 Nov. 1999 16,622/776/ SR William Lacy Swing 1,075 (USA) (2003) Côte d’Ivoire(2002-) UNOCI4 (PKO), S/RES/1528 April 2004 7,849/195/992 SR Pierre Schori (Sweden) (2005) Eritrea-Ethiopia UNMEE (PKO) S/RES/1312 July 2000 2,062/222/- Pending appointment in (1998-2000) January 2007 Guinea-Bissau (1998-1999) UNOGBIS (PBO), S/RES/1216 March 1999 -/2/1 SR Joao Bernardo Honwana (Mozambique) (2004) succeeded by Shola Omoregie (Nigeria) (2006) Liberia (1989-2005) UNMIL (PKO), S/RES/1509 Sept. 2003 14,334/207/1,097 SR Alan Doss (United King- dom) (2005) Morocco-Western MINURSO (PKO) Sept. -

Tanzania's Role in Burundi's Peace Process

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE TANZANIA’S ROLE IN BURUNDI’S PEACE PROCESS STUDENT: SAID J K AMEIR SUPERVISOR DR. ABDUL LAMIN In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Degree of Maters in the International Relations, The Graduate School for the Humanities and Social Sciences, Faculty of Humanitaries, UNIVERSITY OF WITWATERSRAND DECLARATION I declare that this research work is my own, unaided. It has neither been presented before at Wits University nor in any other Universities for any other award. Signed by Said J K Ameir ………………………… This …… day of ……. …. 2008 i DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my family which cares for most of my progress in life. First, my parents who raised and made me became who I am today. I pay special tribute to my father who aside from his decade-long illness has never hesitated to allow me to travel and never bothered by my absence. He has always inspired, motivated and supported me in all my endeavours in life including this one. My wife also deserves special tribute for the undue difficulties she went through, during my absence, when she gave birth to our lovely son Farez. Tribute also goes to my children Mgeni, Lulu and Kauthar for respecting my decision to come to Wits, something which shows that we share the same vision as a family. ii ACKOWLEDGEMENT This research work would not have been possible without the assistance and contribution, by one way or another, of many people. I would therefore like to express my gratitude to the following: First is my supervisor Dr Abdul Lamin for his professional guidance and his steadfast encouragement from the presentation of my first draft proposal to the last chapter. -

5134 ISS Monograph 171.Indd

ISS MONOGRAPH 171 ISS Head Offi ce Block D, Brooklyn Court 361 Veale Street New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 346-9570 E-mail: [email protected] Th e Burundi ISS Addis Ababa Offi ce 1st Floor, Ki-Ab Building Alexander Pushkin Street PEACE CONDITIONAL TO CIVIL WAR FROM PROCESS: THE BURUNDI PEACE Peace Process Pushkin Square, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Th is monograph focuses on the role peacekeeping Tel: +251 11 372-1154/5/6 Fax: +251 11 372-5954 missions played in the Burundi peace process and E-mail: [email protected] From civil war to conditional peace in ensuring that agreements signed by parties to ISS Cape Town Offi ce the confl ict were adhered to and implemented. 2nd Floor, Armoury Building, Buchanan Square An AU peace mission followed by a UN 160 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock, South Africa Tel: +27 21 461-7211 Fax: +27 21 461-7213 mission replaced the initial SA Protection Force. E-mail: [email protected] Because of the non-completion of the peace ISS Nairobi Offi ce process and the return of the PALIPEHUTU- Braeside Gardens, Off Muthangari Road FNL to Burundi, the UN Security Council Lavington, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 386-1625 Fax: +254 20 386-1639 approved the redeployment of an AU mission to E-mail: [email protected] oversee the completion of the demobilisation of ISS Pretoria Offi ce these rebel forces by December 2008. Block C, Brooklyn Court C On 18 April 2009, at a ceremony to mark the 361 Veale Street ON beginning of the demobilisation of thousands New Muckleneuk, Pretoria, South Africa DI Tel: +27 12 346-9500 Fax: +27 12 460-0998 TI of PALIPEHUTU-FNL combatants, Agathon E-mail: [email protected] ON Rwasa, leader of PALIPEHUTU-FNL, gave up AL www.issafrica.org P his AK-47 and military uniform. -

International Organizations

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS EUROPEAN SPACE AGENCY (E.S.A.) Headquarters: 8–10 Rue Mario Nikis, 75738 Paris Cedex 15, France phone 011–33–1–5369–7654, fax 011–33–1–5369–7560 Chairman of the Council.—Per Tegne´r. Director General.—Jean-Jacques Dordain. Member Countries: Austria Greece Spain Belgium Ireland Sweden Denmark Italy Switzerland Finland Netherlands United Kingdom France Norway Germany Portugal Cooperative Agreement.—Canada. European Space Operations Center (E.S.O.C.), Robert-Bosch-Str. 5, D–64293 Darmstadt, Germany, phone 011–49–6151–900, fax 011–49–6151–90495. European Space Research and Technology Center (E.S.T.E.C.), Keplerlaan 1, NL–2201, AZ Noordwijk, ZH, The Netherlands, phone 011–31–71–565–6565; Telex: 844–39098, fax 011–31–71–565–6040. European Space Research Institute (E.S.R.I.N.), Via Galileo Galilei, Casella Postale 64, 00044 Frascati, Italy. Phone, 011–39–6–94–18–01; fax 011–39–6–9418–0280. Washington Office (E.S.A.), Suite 7800, 955 L’Enfant Plaza SW. 20024. Head of Office.—Frederic Nordlund (202) 488–4158, fax 488–4930, [email protected]. INTER-AMERICAN DEFENSE BOARD 2600 16th Street 20441, phone 939–6041, fax 387–2880 Chairman.—MG Keith M. Huber, U.S. Army. Vice Chairman.—MG Dardo Juan Antonio Parodi, Army, Argentina. Secretary.—CAPT Jaime Navarro, U.S. Navy. Deputy Secretary for— Administration.—MAJ Richard D. Phillips, U.S. Army. Conference.—C/F Jose Da Costa Monteiro, Brazil, Navy. Finance.—MAJ Dan McGreal, U.S. Army. Information Management.—LTC Thomas Riddle, U.S. Army. Protocol.—MAJ Ivonne Martens, U.S. -

Download the Publication

MARCH 2012 WORKING GROUP SERIES PAPER NO. 2 “United We Stand, Divided We Fall:” The Sudans After the Split Alan Goulty s the situation in and between the Republic of Sudan (North) and the new na- Wilson Center tion of South Sudan deteriorates, I thought it timely to call again on the expertise Nuredin Satti A UNESCO (Ret) within the ranks of the Africa Program’s Sudan Working Group to shed some light on Introduction by developments. Therefore, two foremost experts, who are also the co-chairs of our working Steve McDonald Wilson Center group – Ambassador Alan Goulty, former UK Ambassador to Sudan and Special Envoy to Darfur, and Ambassador Nureldin Satti, a senior Sudanese diplomat and former United Nations’ Special Representative of the Secretary General – have agreed to pull together these recent updates. They are written specifically from the views of the North and South. Ambassador Satti is currently living in Khartoum, and is well placed to fol- low events there closely. Ambassador Goulty, while now a resident in Washington, DC, travels frequently to South Sudan. WORKING GROUP SERIES PAPER NO. 2 While the papers give a valuable update on current events, including the ongo- ing conflicts in Abyei, South Kordofan, and the Nuba Mountains, the implementa- tion of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), North and South conflicts on oil revenue, and internal political rivalry and governance issues, they also examine the mindsets, beliefs, and biases of the leadership of both sides that have led to the current situation. Unique insights are given into the psyche of both entities, including an examination of the differences between a divided National Congress Party (NCP) in Sudan and the Islamist movements prominent in the “Arab Spring” events over the last year in their Arab neighbors. -

International Organizations

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS EUROPEAN SPACE AGENCY (E.S.A.) Headquarters: 8–10 Rue Mario Nikis, 75738 Paris Cedex 15, France phone 011–33–1–5369–7654, fax 011–33–1–5369–7560 Chairman of the Council.—Per Tegne´r. Director General.—Jean-Jacques Dordain. Member Countries: Austria Greece Portugal Belgium Ireland Spain Denmark Italy Sweden Finland Luxembourg Switzerland France Netherlands United Kingdom Germany Norway Cooperative Agreement.—Canada. European Space Operations Center (E.S.O.C.), Robert-Bosch-Str. 5, D–64293 Darmstadt, Germany, phone 011–49–6151–900, fax 011–49–6151–90495. European Space Research and Technology Center (E.S.T.E.C.), Keplerlaan 1, NL–2201, AZ Noordwijk, ZH, The Netherlands, phone 011–31–71–565–6565, Telex: 844–39098, fax 011–31–71–565–6040. European Space Research Institute (E.S.R.I.N.), Via Galileo Galilei, Casella Postale 64, 00044 Frascati, Italy, phone 011–39–6–94–18–01, fax 011–39–6–9418–0280. Washington Office (E.S.A.), 955 L’Enfant Plaza, SW., Suite 7800, 20024. Head of Office.—Frederic Nordlund (202) 488–4158, fax 488–4930, [email protected]. INTER-AMERICAN DEFENSE BOARD 2600 16th Street, NW., 20441, phone (202) 939–6041, fax 387–2880 Chairman.—LTG Jorge Armando de Almeida Ribiero, Army, Brazil. Vice Chairman.—GB Thomas Pena y Lillo, Army, Bolivia. Secretary.—CAPT Jaime Navarro, U.S. Navy. Deputy Secretary for— Administration.—MAJ Jaime Adames, U.S. Air Force. Conference.—Cel Heldo F. de Souza, Army, Brazil. Information Management.—LTC Michael Cobb, U.S. Army. Protocol.—CAPT William Vivoni, U.S. -

Africa Two Views on the Crisis in Sudan

programAfrica two views on the crisis in sudan Nureldin Satti, UNESCO (Ret) August 2010 John Prendergast and Laura Jones, Enough Project Introduction by Steve McDonald and Alan Goulty, Woodrow Wilson Center Working Group Series Paper No. 1 Based on the Expert Policy Working Group on Sudan of the Africa Program Working Group Series Paper No. 1 SUdan at A CROSSROADS UPDATE: During the first week of August, at a high level U.S. Government meeting on Sudan, tensions erupted be- tween senior administration officials over disagreements on the issues of Darfur, management of the referendum, and incentives and pressures on the Bashir government, which are the focus of this report. Foreign Policy Magazines Blog, the Cable, written by Josh Rogin, reported the clash on August 13, 2010, saying a memo had been sent forward to President Obama for determination, but the end result could be the reassignment of Special Envoy Scott Gration. The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, not been publicly shared, have served an invaluable pur- under its Africa Program and Project for Leadership and pose of linking voices and interests not always in contact Building State Capacity, has been, with the support of the with one another, and in spinning off public elements, Open Society Institute, conducting an such as the conference on Sudan on-going effort to engage and inform held on June 14, 2010, with for- policy makers on issues important to mer South African President Thabo U.S. national interests. This takes the Mbeki and UN Special Representa- form of open public conferences or tive of the Secretary General, Haile presentations, closed policy working Menkerios, when they spoke on UN groups, and occasional publications.