SEO, MINJUNG, DMA Ernest Bloch's Musical Style from 1910 To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIM's First Artistic Director Was Ernest Bloch, a Swiss Composer and Teacher Who Came to Cleveland from New York City

BLOCH, ERNEST (24 July 1880-15 July 1959), was an internationally known composer, conductor, and teacher recruited to found and direct the CLEVELAND INSTITUTE OF MUSIC in 1920. Bloch was born in Geneva, Switzerland. The son of Sophie (Brunschwig) and Maurice (Meyer) Bloch, a Jewish merchant, Bloch showed musical talent early and determined that he would become a composer. His teen years were marked by important study with violin and composition masters in various European cities. Between 1904 and 1916, he juggled business responsibilities with composing and conducting. In 1916 Bloch accepted a job as conductor for dancer Maud Allen's American tour. The tour collapsed after 6 weeks, but performances of his works in New York and Boston led to teaching positions in New York City. During the Cleveland years (1920-25), Bloch completed 21 works, among them the popular Concerto Grosso, which was composed for the students' orchestra at the Cleveland Institute of Music. His contributions included an institute chorus at the CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART, attention to pedagogy especially in composition and theory, and a concern that every student should have a direct and high-quality aesthetic experience. He taught several classes himself. After disagreements with Cleveland Institute of Music policymakers, he moved to the directorship of the San Francisco Conservatory. Following some years studying in Europe, Bloch returned to the U.S. in 1939 to teach at the Univ. of Calif.-Berkeley. He retired in 1941. His students over the years included composers Roger Sessions and HERBERT ELWELL. Bloch composed over 100 works for a variety of individual instruments and ensemble sizes and won over a dozen prestigious awards. -

Interpretive Sign

1880 Ernest Bloch 1959 ROVEREDO GENEVA MUNICH FRANKFURT PARIS LONDON BOSTON NEW YORK CLEVELAND CHICAGO SANTA FE BERKELEY SAN FRANCISCO PORTLAND AGATE BEACH Composer Philosopher Humanist Photographer Mycophagist Beachcomber THOMAS BEECHAM CLAUDE DEBUSSY ALBERT EINSTEIN FRIDA KAHLO SERGE KOUSSEVITSKY GUSTAV MAHLER YEHUDI MENUHIN ZARA NELSOVA DIEGO RIVERA LEOPOLD STOKOWSKI IGOR STRAVINSKY The First American Period, comprising Unpublished Student Works (Geneva, The Second European Period New York (1916-20), Cleveland (1920-25), The Second American period, incorporating the “Agate Beach Years” (1941-59) Brussel, Frankfurt, Munich, Paris) (Switzerland, France, Italy) 1880-1903 1916-1930 San Francisco (1925-30) 1930-1938 1939-1959 Ernest Bloch was born in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1880. Although Bloch moved to New York in In his retreat at Roveredo-Capriasca, Switzerland, he immersed The Stern trust fund for Bloch was administered by the drive from here. The next day she sends a telegram. On the his parents were not particularly artistic, music called to Bloch 1916. Because success had himself in a study of Hebrew in preparation for the composition University of California at Berkeley. Upon his return from his 11th I’ll go and pick her up in Oswego. In the meantime I’ve even as a child. At the age of 9 he began learning to play the violin, eluded him in Europe, he of his Sacred Service (Avodath Hakodesh), which had its debut eight year sabbatical, Bloch was to occupy an endowed chair at discovered a really nice path, flat, which among wild forests quickly proving himself to be a prodigy. By the age of 11, he vowed took a job as the orchestral in Turin, Italy, in 1934, followed the university in fulfillment of the terms surrounding the Stern leads to another beach, huge, empty, on the other side of a to become a composer and then ritualistically burned the written director for a new modern- by performances in Naples, fund. -

Ernest Bloch (1880-1959) Three Nocturnes (1924) Andante Andante Quieto Tempestoso

Ernest Bloch (1880-1959) Three Nocturnes (1924) Andante Andante quieto Tempestoso Bloch was born into a Jewish family in Geneva - the son of a clock-maker. He learned the violin and composition, initially in Geneva, but in his teens he moved to Brussels to study with Eugène Ysaÿe, then to Frankfurt, Munich and Paris. In his mid-twenties he returned to Geneva where he married and entered his father's firm as a bookkeeper and salesman, along with occasional musical activities – composing, conducting and lecturing. His opera Macbeth was successfully performed at the Paris Opéra-Comique in 1910. Six years later he went to the United States, initially to conduct a dance company's tour. The tour collapsed, but he secured a job teaching composition at a New York music college and his wife and children joined him there. Performances of new works including some with a Jewish flavour ( Trois poèmes juifs and Schelomo) increased his visibility. His popular association with 'Jewish' music was enhanced by G.Schirmer publishing his works with a characteristic trademark logo – the six-pointed Star of David with the initials E.B. in the centre. From 1920-5 he served as the founding director of the Cleveland Institute of Music and from 1925–30 as director of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. The Conservatory subsidised his return to Switzerland in the 1930s allowing him to compose undisturbed. But with the rise of the Nazis and the need to maintain his American citizenship, in 1939 he returned to a chair at UC Berkeley which he held until his retirement to Agate Bay, Oregon, where he continued to compose widely, took photographs and polished agates. -

Am<Eriica~ Ttlh<E Lalrnd of Lpromiise and F Ullfiillllmelrntt for Olrn<E Of

September 7, 1918 MUSICAL AMERICA 5 Am<eriica~ ttlh<e lalrnd of lPromiise and Fullfiillllmelrntt for Olrn<e of Swiitzerlland~ s Most Giiftted SolrnS~ lErlrn<esit Blloch Meteoric Rise to F arne in Our New World Opened Its Arms to Country of This Signally Him-Found More Real Crit Gifted Composer - Writer Ical Acumen Here Than in ,. Notes Characteristically Amer Europe -His Great Quartet ican Qualities in Mr. Bloch-A Finished Within Stone's Man of Action, Broad Interest Throw of the "L"-Has Cast and Sympathies, and Flaming in His Lot with Us-Potential Imagination - His "] ewish Influence on Our Music Side" - Early Career and with every contemporary current. His Studies Judaism saved him. from being swept away by any of them. It gave him By CESAR SAERCHINGER nourishment when after all his studies with different masters he turned within T is considerably more than a year himself to study, as he expressed it, I since Ernest Bloch stirred musical "with nature and with myself." And ~ believe that his coming to America, New York with a great orchestral con when .he had evolved this new style of cert consisting entirely of his own works his own, is of still greater significance. -works of such magnitude and bold de For the problem that Bloch has solved sign as to arrest the attention of every for himself, musical America must solve for herself also. We must emerge from musician and critic in America. Many this European welter into a freer, were enthusiastic, others were hostile, brighter world of our own, permeated few were indifferent-a fairly good sign with the spirit of our own ideals and that ·the works were important. -

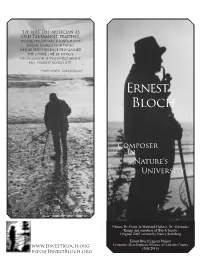

Ernest Bloch

“He was the musician as Old Testament prophet, whose speech was thunder and whose glance lightning, whose very presence proclaimed the divine fire by which, on occasion, a bystander might feel himself scorched.” ” Yehudi Menuhin, “Unfinished Journey” Ernest Bloch Composer in Photo by Walt Dyke Walt Photo by Nature’s University Photo by Lucienne Bloch, courtesy Old Stage Studios Editors Dr. Frank Jo Maitland Geltner, Dr. Alexander Knapp and members of Bloch family. Original 2005 version by Nancy Steinberg Ernest Bloch Legacy Project Economic Development Alliance of Lincoln County www.ernestbloch.org (July 2018) [email protected] Chronological List of Ernest Bloch’s Compositions 1923 Enfantines: Ten Pieces for Children, piano (Fischer) Compiled by Alexander Knapp from his “Alphabetical List of Bloch’s Published Five Sketches in Sepia: Prélude – Fumées sur la ville – Lucioles – Incertitude – and Unpublished Works” in Ernest Bloch Studies, co-edited by Alexander Knapp Epilogue, piano (Schirmer) Mélodie: violin and piano (Fischer) and Norman Solomon, Cambridge University Press, 2016. Night, string quartet (Fischer) The years shown indicate date of completion, not date of publication. Nirvana: Poem for Piano (Schirmer) Within each year, works are listed in alphabetical order. Paysages (Landscapes) – Three Pieces for String Quartet: North – Alpestre - *Unpublished work – manuscript extant. Tongataboo (Fischer) **Unpublished - manuscript lost. Piano Quintet No. 1 (Schirmer) 1924 From Jewish Life: Three Sketches for Violoncello and Piano (also -

Finding Aid for the Ernest Bloch Miscellaneous Acquisitions Collection, 1926, 1978 AG 103

Center for Creative Photography The University of Arizona 1030 N. Olive Rd. P.O. Box 210103 Tucson, AZ 85721 Phone: 520-621-6273 Fax: 520-621-9444 Email: [email protected] URL: http://creativephotography.org Finding aid for the Ernest Bloch Miscellaneous Acquisitions Collection, 1926, 1978 AG 103 Finding aid updated by Meghan Jordan, June 2016 AG 103: Ernest Bloch Miscellaneous Acquisitions Collection, 1926, 1978 - page 2 Ernest Bloch Miscellaneous Acquisitions Collection, 1926, 1978 AG 103 Creator Center for Creative Photography Abstract This collection contains materials documenting the life and career of Ernest Bloch (1880- 1959), composer and photographer. Each group of materials will be described separately. The collection is active. Quantity/ Extent 1 linear foot Language of Materials English Biographical Note Ernest Bloch was born July 24, 1880 in Geneva, Switzerland. He began composing music after receiving a violin at the age of 9. He studied music and composition in Brussels, Germany, and Paris before settling in the United States in 1916 and becoming an American citizen in 1924. Bloch is celebrated as one of the most renowned 20th century composers, and received many honors, including the Coolidge Prize (1919), the Musical American Prize (1928), the first Gold Medal in Music (1942), and the honor of Professor Emeritus of Music (1952) from the University of California at Berkeley. Bloch held multiple teaching positions throughout the U.S. He died in Portland, Oregon on July 15, 1959. Bloch’s photography was discovered by Eric B. Johnson in 1970. Bloch became interested in photography at the age of sixteen. Bloch worked with black and white photography and produced small-format images mounted in albums as well as stereoscopic views. -

ETHEL LEGINSKA: PIANIST, FEMINIST, CONDUCTOR Extraordinalre, and COMPOSER

CHRISTOPHER NEWPORT UNIVERSITY ETHEL LEGINSKA: PIANIST, FEMINIST, CONDUCTOR EXTRAORDINAlRE, AND COMPOSER FALK SEMINAR RESEARCH PAPER MUSIC 490 BY MELODIE LOVE GRIFFIN NEWPORT NEWS, VIRGINIA DECEMBER 1993 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank, first, the Minnesota Historical Society for providing rare, dated material essential to the completion of this paper, namely, articles from the Minneapolis Journal and the Duluth Herald. Second, her mother, who patiently endured nearly a year of irritability, frustration, stubborn persistence, and long midnight hours the author experienced in the completion of this paper, not to mention a day's trip to Washington, D.C. on short notice. Third, the Library of Congress, for providing several of Ethel Leginska's pUblished works. Fourth, the Falk Seminar Professor/Advisor, Dr. Brockett, for his assistance in gathering articles, contributing a title, and for his insistence on perfection, motivating the author of this paper to strive for perfection in all of her coursework and other undertakings, eschewing mediocrity. Last, but most importantly, the author gives thanks to the Lord Jesus Christ, for supplying all her needs along the way, including the strength to persevere when it seemed, at times, that this project was too much to handle and should have been dropped. Ethel Leginska (1886-1970) was widely acclaimed as a concert pianist and, later, as a conductor at a time when women were considered by some to be no fitting match for men as concert pianists, and it was preposterous to think a woman could take up the baton for a major orchestra. However, very little seems to have been said about her as a composer, and her compositions have been basically overlooked for close scrutiny. -

Romantic Voices Danbi Um, Violin; Orion Weiss, Piano; with Paul Huang, Violin

CARTE BLANCHE CONCERT IV: Romantic Voices Danbi Um, violin; Orion Weiss, piano; with Paul Huang, violin July 30 PROGRAM OVERVIEW Violinist Danbi Um embodies the tradition of the great Romantic style, her Sunday, July 30 natural vocal expression coupled with virtuosic technique. Partnered by pia- 6:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School nist Orion Weiss, making his Music@Menlo debut, she offers a program of music she holds closest to her heart, a stunning variety of both favorites and SPECIAL THANKS delightful discoveries. Music@Menlo dedicates this performance to Hazel Cheilek with gratitude for her generous support. ERNEST BLOCH (1880–1959) JENŐ HUBAY (1858–1937) Violin Sonata no. 2, Poème mystique (1924) Scènes de la csárda no. 3 for Violin and Piano, op. 18, Maros vize (The River GEORGE ENESCU (1881–1955) Maros) (ca. 1882–1883) Violin Sonata no. 3 in a minor, op. 25, Dans le caractère populaire roumain (In FRITZ KREISLER (1875–1962) Romanian Folk Character) (1926) Midnight Bells (after Richard Heuberger’s Midnight Bells from Moderato malinconico The Opera Ball) (1923) Andante sostenuto e misterioso Allegro con brio, ma non troppo mosso ERNEST BLOCH Avodah (1928) INTERMISSION JOSEPH ACHRON (1886–1943) ERICH WOLFGANG KORNGOLD (1897–1957) Hebrew Dance, op. 35, no. 1 (1913) Four Pieces for Violin and Piano from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s CONCERTS BLANCHE CARTE Danbi Um, violin; Orion Weiss, piano Much Ado about Nothing, op. 11 (1918–1919) Maiden in the Bridal Chamber March of the Watch PABLO DE SARASATE (1844–1908) Intermezzo: Garden Scene Navarra (Spanish Dance) for Two Violins and Piano, op. -

Ernest Bloch in San Francisco

Min-Ad: Israel Studies in Musicology Online David Z. Kushner – Ernest Bloch in San Francisco ERNEST BLOCH IN SAN FRANCISCO DAVID Z. KUSHNER Ernest Bloch’s arrival on American shores, on 30 July 1916, marked the beginning of his lengthy career in the United States. Like other European fortune seekers who left behind a war-stricken Europe, which offered little hope for financial survival, he went through a period of economic instability, networking with his connections and experimenting with a variety of musical and artistic enterprises. Despite early financial disappointment as conductor of an ill-fated tour by the Maud Allan dance company, he capitalized on such European connections as the Flonzaley Quartet, and support from such influential luminaries as Paul Rosenfeld, Waldo Frank, and Olin Downes. He was thus able to get important performances and to cement further a network of devoted yea- sayers. Brief teaching engagements at the recently founded Mannes Music School in New York (1917- 20), the Hartt School of Music (1919-20), and the Bird School in Peterborough, New Hampshire (summer 1919) paved the way toward his appointment as director of the newly formed Cleveland Institute of Music (1920-25). During his final year there, increasing strife between the maestro, his assistant director, and the trustees of the school eventually led to his resignation.1 Bloch once again was called by fate and by the invitation of Ada Clement and Lillian Hodghead to go further west to serve as artistic director and teacher at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.2 Bloch was a public figure by then, and the press heralded his arrival on the western frontier. -

Ernest Bloch Schelomo, Hebraic Rhapsody for Solo Cello and Large

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Ernest Bloch Born July 24, 1880, Geneva, Switzerland. Died July 15, 1959, Portland, Oregon. Schelomo, Hebraic Rhapsody for Solo Cello and Large Orchestra (1916) Swiss by birth; trained in Brussels, Frankfurt, Dresden, and Paris; and first recognized in the United States, Ernest Bloch has come to be known primarily as a Jewish composer. But, as Yehudi Menuhin, one of his strongest champions, noted, Bloch was “a great composer without any narrowing qualifications whatever.” Bloch was always interested in exploring other lands and other cultures through music—one of his first compositions was an Oriental Symphony he wrote at the age of fifteen—but he soon came to realize that it was his own Jewish roots that spoke most strongly to him. Many of Bloch’s best-known works, particularly those written in the second decade of the twentieth century, are dominated by his Jewish consciousness—“a voice,” as he wrote, “which seemed to come from far beyond myself, far beyond my parents.” In the end, Bloch admitted that he couldn’t distinguish to what extent his music was Jewish and to what extent “it is just Ernest Bloch.” Bloch was not interested in authenticity; he was after a different kind of truth. “I do not propose or desire to attempt a reconstruction of the music of the Jews,” he wrote, “or to base my work on melodies more or less authentic. I am not an archaeologist. I believe that the most important thing is to write good and sincere music—my music. It is rather the Hebrew spirit that interests me, the complex, ardent, agitated soul that vibrates for me in the Bible.” After the start of World War I, Bloch was drawn to the biblical book of Ecclesiastes. -

Ernest Bloch: the Cleveland Years (1920-25)

Min-Ad: Israel Studies in Musicology Online David Z. Kushner – Ernest Bloch: The Cleveland Years (1920-25) Ernest Bloch: The Cleveland Years (1920-25) DAVID Z. KUSHNER Ernest Bloch (1880-1959) spent the summer of 1919 teaching music to young children, including his daughters Suzanne and Lucienne, at the school founded in Peterboro, New Hampshire by Joanne Bird Shaw. Its purpose was to provide an alternative education for her children and for those of some of her neighbors. Toward that end, she engaged persons prominent in the arts to teach there. A stenographic account of Bloch’s classes,1 including comments by the instructor and his pupils, offer striking testimony to the fact that, even at this juncture in his fledgling career in the United States, the composer had little regard for traditional textbooks. He advocated instead direct access to the works of the masters. With his youthful charges, emphasis was placed on aural training and eurhythmics.2 His reputation secure as a composer, the result of successful performances of the works comprising the “Jewish Cycle,” most notably Trois Poèmes juifs, Schelomo, and Israel, Bloch, after spending the 1919-20 academic year teaching at David Mannes’s3 newly established music school in New York, accepted a “call from the wild,” to serve as founding director of the as yet unformed Cleveland Institute of Music. It is of no little moment that Mannes observed that Bloch, who was anxious to develop his career as a composer, was “born to create and not to observe a teacher’s schedule and a routine scholastic *It is my distinct pleasure to be a contributor to the special edition of Min-Ad in honor of Professor Emerita Bathia Churgin, who celebrated her 80th birthday last year. -

Ben-Haim · Bloch · Korngold

Ben-Haim · Bloch · Korngold Cello Concertos Raphael Wallfisch BBC National Orchestra of Wales Łukasz Borowicz VOICES IN THE WILDERNESS CELLO CONCERTOS BY EXILED JEWISH COMPOSERS Paul Ben-Haim (1897–1984) Cello Concerto (1962) 22'01 1 Allegro giusto 9'01 2 Sostenuto e languido 6'23 3 Allegro gioioso 6'37 Ernest Bloch (1880–1959) Symphony for Cello & Orchestra (1954) 17'52 4 Maestoso 3'25 5 Agitato 9'23 6 Allegro deciso 5'04 Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897–1957) All rights of the producer and of the owner of the work reserved. 7 Concerto in D in one movement 13'17 Unauthorized copying, hiring, renting, public performance and broadcasting 8 Tanzlied des Pierrot (from the opera Die tote Stadt) 4'17 of this record prohibited. cpo 555 273–2 (1880–1959) Ernest Bloch Recorded 31 October – 2 November 2018, BBC Hoddinott Hall 9 Vidui (1st movement of the Baal Shem-Suite) 3'00 Recording produced by Simon Fox-Gál Balance engineer: Simon Smith, BBC Wales 10 Nigun (2nd movement of the Baal Shem-Suite) 6'53 Edited by Jonathan Stokes and Simon Fox-Gál T.T.: 63'25 Executive Producers: Burkhard Schmilgun/Meurig Bowen Cover Painting: Felix Nussbaum, »Der Leierkastenmann«, 1931, Raphael WallfischVioloncello Berlin, Berlinische Galerie BBC National Orchestra of Wales © Photo: akg-images, 2019; Design: Lothar Bruweleit cpo, Lübecker Str. 9, D–49124 Georgsmarienhütte Łukasz Borowicz Conductor ℗ 2019 – Made in Germany Łukasz Borowicz © Katarzyna Zalewska Anmerkungen des Cellisten Paul Ben-Haim: sich alsbald Paul Ben-Haim (hebr. »Sohn des Hein- Konzert für Violoncello und Orchester rich«) nannte, ins Exil ging.