Ernest Bloch in San Francisco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galka Scheyer: Eine Jüdische Kunsthändlerin (Braunschweig, 26-28 Nov 19)

Galka Scheyer: eine jüdische Kunsthändlerin (Braunschweig, 26-28 Nov 19) Braunschweig, 26.–28.11.2019 Eingabeschluss: 30.04.2019 Katrin Keßler, Bet Tfila - Forschungsstelle für jüdische Architektur in Europa [English below] Die Malerin, Kunsthändlerin und –sammlerin Galka Scheyer, geboren 1889 als Emilie Esther Schey- er, stammte aus einer Braunschweiger Unternehmerfamilie, der die seinerzeit größte Konservenfa- brik der Stadt gehörte. Für ein jüdisches Mädchen aus gutbürgerlichem Haus ist ihre Biographie überraschend. Ihr Weg führte sie bis in die USA, wo sie seit 1924 lebte und 1945 in Hollywood starb. Eine allgemeine Bekanntschaft erlangte sie nicht, wohl aber die „Blaue Vier“, die sie gemein- sam mit vier anerkannten Künstlern des Weimarer Bauhauses gründete: Paul Klee, Wassily Kand- insky, Lyonel Feininger und Alexej von Jawlensky. Anfangs hatte Emilie Scheyer eigene künstlerische Ambitionen. Im Alter von 16 Jahren hatte sie Deutschland verlassen, um in England, Frankreich, Belgien und der Schweiz Malerei, Bildhauerei und Musik zu studieren. In der Schweiz lernte sie 1916 Jawlensky kennen und beschloss, nicht mehr selbst künstlerisch tätig zu sein, sondern ihre Energie der Vermittlung und dem Verkauf sei- ner Werke zu widmen. Mit der Gründung der Künstlergruppe „Blaue Vier“ im Jahre 1924 wurde sie zur offiziellen Kunsthändlerin der „vier blauen Könige“, wie sie selbst „ihre“ Künstler nannte. Sie organisierte zahlreiche Ausstellungen und Lichtbildvorträge, unternahm Reisen durch Europa, die USA und Asien. Mit einer internationalen Tagung wollen die Bet Tfila – Forschungsstelle für jüdische Architektur und das Städtische Museum Braunschweig in Kooperation mit der Stadt Braunschweig diese bedeutende Tochter der Stadt in den Blickpunkt nehmen. Trotz der großen Bedeutung der von ihr vertretenen Künstler in der Kunstgeschichte des frühen 20. -

CIM's First Artistic Director Was Ernest Bloch, a Swiss Composer and Teacher Who Came to Cleveland from New York City

BLOCH, ERNEST (24 July 1880-15 July 1959), was an internationally known composer, conductor, and teacher recruited to found and direct the CLEVELAND INSTITUTE OF MUSIC in 1920. Bloch was born in Geneva, Switzerland. The son of Sophie (Brunschwig) and Maurice (Meyer) Bloch, a Jewish merchant, Bloch showed musical talent early and determined that he would become a composer. His teen years were marked by important study with violin and composition masters in various European cities. Between 1904 and 1916, he juggled business responsibilities with composing and conducting. In 1916 Bloch accepted a job as conductor for dancer Maud Allen's American tour. The tour collapsed after 6 weeks, but performances of his works in New York and Boston led to teaching positions in New York City. During the Cleveland years (1920-25), Bloch completed 21 works, among them the popular Concerto Grosso, which was composed for the students' orchestra at the Cleveland Institute of Music. His contributions included an institute chorus at the CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART, attention to pedagogy especially in composition and theory, and a concern that every student should have a direct and high-quality aesthetic experience. He taught several classes himself. After disagreements with Cleveland Institute of Music policymakers, he moved to the directorship of the San Francisco Conservatory. Following some years studying in Europe, Bloch returned to the U.S. in 1939 to teach at the Univ. of Calif.-Berkeley. He retired in 1941. His students over the years included composers Roger Sessions and HERBERT ELWELL. Bloch composed over 100 works for a variety of individual instruments and ensemble sizes and won over a dozen prestigious awards. -

Maven of Modernism: Galka Scheyer in California April 7–Sept

October 2016 Media Contacts: Leslie C. Denk | [email protected] | (626) 844-6941 Emma Jacobson-Sive | [email protected] | (323) 842-2064 Maven of Modernism: Galka Scheyer in California April 7–Sept. 25, 2017 Pasadena, CA—The Norton Simon Museum presents Maven of Modernism: Galka Scheyer in California, an exhibition that delves into the life of Galka Scheyer, the enterprising dealer responsible for the art phenomenon the “Blue Four”—Lyonel Feininger, Alexei Jawlensky, Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. In California, through the troubling decades of the Great Depression and the Second World War, German- born Scheyer (1889–1945) single-handedly cultivated a taste for their brand of European modernism by arranging exhibitions, lectures and publications on their work, and negotiating sales on their behalf. Maven of Modernism presents exceptional examples from Scheyer’s personal collection by the Blue Four artists, as well as works by artists including Alexander Archipenko, László Moholy-Nagy, Pablo Picasso Head in Profile, 1919 Emil Nolde (German, 1867-1956) and Diego Rivera, which was given to the Pasadena Art Institute in the Watercolor and India ink on tan wove paper 14-1/2 x 11-1/8 in. (36.8 x 28.3 cm) Norton Simon Museum, The Blue Four Galka Scheyer Collection early 1950s. All together, these works and related ephemera tell the © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll, Germany fascinating story of this trailblazing impresario, who helped shape California’s reputation as a burgeoning center for modern art. Galka Scheyer was born Emilie Esther Scheyer in Braunschweig, Germany, in 1889, to a middle-class Jewish family. -

Interpretive Sign

1880 Ernest Bloch 1959 ROVEREDO GENEVA MUNICH FRANKFURT PARIS LONDON BOSTON NEW YORK CLEVELAND CHICAGO SANTA FE BERKELEY SAN FRANCISCO PORTLAND AGATE BEACH Composer Philosopher Humanist Photographer Mycophagist Beachcomber THOMAS BEECHAM CLAUDE DEBUSSY ALBERT EINSTEIN FRIDA KAHLO SERGE KOUSSEVITSKY GUSTAV MAHLER YEHUDI MENUHIN ZARA NELSOVA DIEGO RIVERA LEOPOLD STOKOWSKI IGOR STRAVINSKY The First American Period, comprising Unpublished Student Works (Geneva, The Second European Period New York (1916-20), Cleveland (1920-25), The Second American period, incorporating the “Agate Beach Years” (1941-59) Brussel, Frankfurt, Munich, Paris) (Switzerland, France, Italy) 1880-1903 1916-1930 San Francisco (1925-30) 1930-1938 1939-1959 Ernest Bloch was born in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1880. Although Bloch moved to New York in In his retreat at Roveredo-Capriasca, Switzerland, he immersed The Stern trust fund for Bloch was administered by the drive from here. The next day she sends a telegram. On the his parents were not particularly artistic, music called to Bloch 1916. Because success had himself in a study of Hebrew in preparation for the composition University of California at Berkeley. Upon his return from his 11th I’ll go and pick her up in Oswego. In the meantime I’ve even as a child. At the age of 9 he began learning to play the violin, eluded him in Europe, he of his Sacred Service (Avodath Hakodesh), which had its debut eight year sabbatical, Bloch was to occupy an endowed chair at discovered a really nice path, flat, which among wild forests quickly proving himself to be a prodigy. By the age of 11, he vowed took a job as the orchestral in Turin, Italy, in 1934, followed the university in fulfillment of the terms surrounding the Stern leads to another beach, huge, empty, on the other side of a to become a composer and then ritualistically burned the written director for a new modern- by performances in Naples, fund. -

Kunsthändler Und -Sammler Art Dealers and Collectors

Kunsthändler und -sammler Art dealers and collectors Die Eigentümergeschichte der Kunstwerke aus dem Bestand des Museum Berggruen bildet das Leitmotiv der Ausstellung. Die Namen derer, die mit e history of ownership of the artworks from the collection of the Museum den Werken in Berührung kamen oder deren Eigentum sie waren, lesen sich Berggruen is the leitmotif of the exhibition. e names of those who came wie ein „Who is Who“ der Kunstwelt der ersten Häle des 20. Jahrhunderts: into contact with the works or who owned them read like a "Who's Who" of Kunsthändler wie Alfred Flechtheim, Paul Rosenberg, Daniel-Henry Kahn- the art world of the rst half of the 20th century: Art dealers such as Alfred weiler oder Karl Buchholz, die Klee-Enthusiastin Galka Scheyer sowie die Flechtheim, Paul Rosenberg, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler or Karl Buchholz, Sammler Alphonse Kann, Douglas Cooper und Marie-Laure Comtesse the Klee-enthusiast Galka Scheyer as well as the art collectors Alphonse de Noailles. Kann, Douglas Cooper and Marie-Laure Comtesse de Noailles. Die Kunstwerke rufen damit nicht nur ihre Besitzer und Eigentümer in e artworks do not only remind us of their owners and proprietors, whose Erinnerung, deren Lebensgeschichte in historische Ereignisse eingebettet biographies is embedded in historical events. eir provenances also express ist. Ihre Provenienzen drücken auch die Vielfalt der emen aus, welche die the variety of themes that shape the history of 20th century art: the popula- Geschichte von Kunst im 20. Jahrhunderts prägen: die Popularisierung der risation of Modernism, the development of the international art market, the Moderne, die Entwicklung des internationalen Kunstmarktes, die Emigra- emigration of art dealers and collectors and the translocation of artworks, tion von Kunsthändlern und Sammlern und die Translokation von Kunst- the art policy and the art looting of the National Socialists between 1933 werken, die Kunstpolitik und der Kunstraub der Nationalsozialisten and 1945. -

Paul Klee, 1879-1940 : a Retrospective Exhibition

-— ' 1" I F" -pr,- jpp«_p —^ i / P 1^ j 1 11 111 1 I f^^^r J M • •^^ | Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Library and Archives http://www.archive.org/details/paulklee1879klee PAUL KLEE 1879 1940 A RETROSPECTIVE EXHIBITION ORGANIZED BY THE SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM IN COLLABORATION WITH THE IMSADENA ART MUSEUM 67-19740 © 1967, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York Library of Congress Card Catalogue Number: Printed in the United States of America PARTICIPATING IIVSTITITIOWS PASADENA ART MUSEUM SAN FRANCISCO MUSEUM OF ART COLUMBUS GALLERY OF FINE ARTS CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART WILLIAM ROCKHILL NELSON GALLERY OF ART, KANSAS CITY BALTIMORE MUSEUM OF ART WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY, GALLERY OF ART. ST. LOUIS PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART Paul Klee stated in 1902: "I want to do something very modest, to work out by myself a tiny formal motif, one that my pencil will be able to encompass without any technique..."'. Gradually he intensified his formal and expressive range, proceeding from the tested to the experimental, toward an ever deepening human awareness. Because of his intensive concentration upon each new beginning, categories fall by the wayside and efforts to divide Klee's work into stable groupings remain unconvincing. Even styl- istic continuities are elusive and not easily discernible. There is nothing in the develop- ment of his art that resembles, for example. Kandinsky's or Mondrian s evolution from a representational toward a non-objective mode. Nor is it possible to speak of "periods" in the sense in which this term has assumed validity with Picasso. -

An Exploration of the Availability and Implementation of Undergraduate Degrees in Conducting in the United States Erik Lee Garriott University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 An Exploration of the Availability and Implementation of Undergraduate Degrees in Conducting in the United States Erik Lee Garriott University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Garriott, E. L.(2017). An Exploration of the Availability and Implementation of Undergraduate Degrees in Conducting in the United States. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4100 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Exploration of the Availability and Implementation of Undergraduate Degrees in Conducting in the United States by Erik Lee Garriott Bachelor of Arts Point Loma Nazarene University, 2010 Master of Music California State University Northridge, 2013 _________________________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Conducting School of Music University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: Donald Portnoy, Major Professor Cormac Cannon, Chair, Examining Committee Andrew Gowan, Committee Member Alicia Walker, Committee Member Kunio Hara, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Erik Lee Garriott, -

Ernest Bloch (1880-1959) Three Nocturnes (1924) Andante Andante Quieto Tempestoso

Ernest Bloch (1880-1959) Three Nocturnes (1924) Andante Andante quieto Tempestoso Bloch was born into a Jewish family in Geneva - the son of a clock-maker. He learned the violin and composition, initially in Geneva, but in his teens he moved to Brussels to study with Eugène Ysaÿe, then to Frankfurt, Munich and Paris. In his mid-twenties he returned to Geneva where he married and entered his father's firm as a bookkeeper and salesman, along with occasional musical activities – composing, conducting and lecturing. His opera Macbeth was successfully performed at the Paris Opéra-Comique in 1910. Six years later he went to the United States, initially to conduct a dance company's tour. The tour collapsed, but he secured a job teaching composition at a New York music college and his wife and children joined him there. Performances of new works including some with a Jewish flavour ( Trois poèmes juifs and Schelomo) increased his visibility. His popular association with 'Jewish' music was enhanced by G.Schirmer publishing his works with a characteristic trademark logo – the six-pointed Star of David with the initials E.B. in the centre. From 1920-5 he served as the founding director of the Cleveland Institute of Music and from 1925–30 as director of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. The Conservatory subsidised his return to Switzerland in the 1930s allowing him to compose undisturbed. But with the rise of the Nazis and the need to maintain his American citizenship, in 1939 he returned to a chair at UC Berkeley which he held until his retirement to Agate Bay, Oregon, where he continued to compose widely, took photographs and polished agates. -

Aspects of Jazz and Classical Music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2002 Aspects of jazz and classical music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini Heather Koren Pinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pinson, Heather Koren, "Aspects of jazz and classical music in David N. Baker's Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini" (2002). LSU Master's Theses. 2589. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2589 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASPECTS OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL MUSIC IN DAVID N. BAKER’S ETHNIC VARIATIONS ON A THEME OF PAGANINI A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in The School of Music by Heather Koren Pinson B.A., Samford University, 1998 August 2002 Table of Contents ABSTRACT . .. iii INTRODUCTION . 1 CHAPTER 1. THE CONFLUENCE OF JAZZ AND CLASSICAL MUSIC 2 CHAPTER 2. ASPECTS OF MODELING . 15 CHAPTER 3. JAZZ INFLUENCES . 25 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 48 APPENDIX 1. CHORD SYMBOLS USED IN JAZZ ANALYSIS . 53 APPENDIX 2 . PERMISSION TO USE COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL . 54 VITA . 55 ii Abstract David Baker’s Ethnic Variations on a Theme of Paganini (1976) for violin and piano bring together stylistic elements of jazz and classical music, a synthesis for which Gunther Schuller in 1957 coined the term “third stream.” In regard to classical aspects, Baker’s work is modeled on Nicolò Paganini’s Twenty-fourth Caprice for Solo Violin, itself a theme and variations. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

-Fo Oc Cs>Fiifr[Tftk<L- — Lof <R

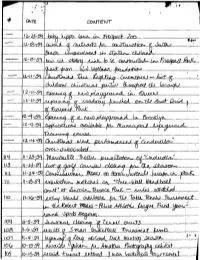

, -fo Oc Cs>fiifr[tfTk<l- — Lof <r - : OXAK" — *5h(VF 6&i-f[/N3 uUPcflUY- J[« (JobL 3 %OAArLdc Mk/J /\ifaxir\Q fU> fbbxJ JUtkLsMc •» • 3 • \HxKxapai tfom pxrz. 5(o '<3>^ 55 5\ 5o (o-3-&\ fa tlJt Brot&* {) 5-22- 45 . c^ J .^^"io^U; 1&uuu^ajp<& CM-M^cyL5ta^ l i /cto^TLT. 6LO^ h&cQtyOte 51 . a -t 15* 35 <?4 u S3 •52. U -CjLl€hj01&-- Iv3l ^tcL?U J^UMj^tO^ zi ^ _.Ei-ciw_p4#_ QoU_. GIMJX ^c^co6 &cJ._^st. Z3 C^dLG— Cr?. fihfoJ^dtf'Gsi 2.2, ^ (jo Z( 2O Q 16 w 17 i ^ 15 4-2-5? <fl 13 II -uSj-f <n. fads - Ste&ttelL TcujrNztrtLti-. .. IP.. of q ..s. - past _ i A 1-13- Q od. .c?_ ttCJL 3 a 2 (-15-59 u % 7 i* DEPARTMEN O F PA R K S ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK REGENT 4-1000 FOR RELEASE THURSDAY, DECEMBER 24, 1959 l-l-l-60M-707199(58) 114 The Department of Parks announces that a •baby- female hippopotamus weighing approximately 70 lbs. was born on November 24, 1959, at the Prospect Park &oo in Brooklyn. The mother, Betsy, now 9 years old, arrived at the Prospect Park &oo on September 8, 1953, and the sire, "Dodger", was 3 years old v/hen he arrived in 1951. However, "Dodger" passed away on October 8, 1959, and will not be around to hand out cigars. The new offspring has been named "'Annie". N.B. s Press photographs may be taken at tine* 12/23/59 DEPARTMEN O F PA R K S ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK REGENT 4-1000 FOR RELEASE SUHDAY, D5CBMHBR 20, 1959 M-l-60M-529Q72(59) 114 The Borough President of Richmond and the Department of Parks announce the award of contracts, in the amount of $2,479,487, for the second stage of construction of the South Beach improvement in Staten Islitnd. -

Universiv Micrcsilms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Tlie sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy.