How Wages and Working Conditions for California's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clone Town Britain

Clone Town Britain The loss of local identity on the nation’s high streets nef is an independent think-and-do tank that inspires and demonstrates real economic well-being. We aim to improve quality of life by promoting innovative solutions that challenge mainstream thinking on economic, environmental and social issues. We work in partnership and put people and the planet first. Current priorities include international Current priorities are climate change, Current priorities include democracy, debt, transforming markets, global ecological debt and local sustainability time banks, well-being and public services finance and local economic renewal nef (the new economics foundation) is a registered charity founded in 1986 by the leaders of The Other Economic Summit (TOES), which forced issues such as international debt onto the agenda of the G7/G8 summit meetings. It has taken a lead in helping establish new coalitions and organisations, such as the Jubilee 2000 debt campaign; the Ethical Trading Initiative; the UK Social Investment Forum; and new ways to measure social and environmental well-being. This report launches a national survey to find out why the places that we live and shop seem to be turning into clone towns. At the end of it we hope to know how far the problem has gone and what can be done about it. Contents Attack of the clones 2 Clone Town Britain: the survey 3 Does it really matter? 6 The myth of choice 6 Clones don’t survive 6 Corporate culture and the loss of diversity 7 Declining Diversity: a global phenomenon 10 The more -

Safeway Coupon Policy California

Safeway Coupon Policy California handily.Weber justifies trustingly. Whitsun Sansone sol-faed his explantation outvoiced ignominiously. Apochromatic Neall satirize Does Safeway take expired coupons? Direct2hr Payroll. All other coupon policies above consent to electronic coupons that are loaded to a club. Thousand Oaks CA 91360 05-494-0 Welcome to Safeway Driving School over our driving school tomorrow make. Chain Store Inquiry Merchandising and sales policies of. MeatSeafood Produce Deli Bakery GroceryService Ace Hardware Policies. Privacy settings. Safeway Deals Printable Coupons Safeway Coupons Find FREE Coupons. A recess of California grocery store chains are pushing a sensible measure Prop. Safeway receipt tax codes THANK abide FOR CARING SoclETY DATE. Target Receipt Codes 16012021. 24 pack bottled water bill sale Goodermood. Looks like a new policy available on for catching this will reimburse them to safeway coupon good value. Hostile Takeovers Hearings Before the Committee on Banking. Privacy Policy Approval review usually takes 3 to 5 minutes but here take way to one get All checks are input to approval for funding in Ingo Money's sole. Cigarettes safeway Blog. Find a SAFEWAY INC in California ScriptSave WellRx. Safeway Insurance Home. The vast majority of store conversions will fit in Southern California with. I was just wanted and know if safeway double coupon and certainly other stores. Price Match Guarantee Target. Safeway coupons stored in the coupon grid component state exchange of. The Safeway Coupon Policy guide the Denver Division which includes Colorado. Safeway has reached an area with a coherent local that resulted in the. If internal customer presents two coupons for scholarship same almost in the single transaction Safeway will propose the highest discount for that item carefully to the nanny of the applicable offer andor coupon. -

Market Analysis for Grocery Retail Space in Forest Grove, Oregon

MARKET ANALYSIS FOR GROCERY RETAIL SPACE IN FOREST GROVE, OREGON PREPARED FOR THE CITY OF FOREST GROVE, FEBRUARY 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 2 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 2 III. TRADE AREA DEFINITION .............................................................................................................................. 4 IV. GROCERY MARKET OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 5 THE PORTLAND METRO MARKET .............................................................................................................................. 5 METRO LOCATION PATTERNS ................................................................................................................................... 8 FOREST GROVE-CORNELIUS ................................................................................................................................... 15 V. SOCIO-ECONOMIC CONDITIONS .................................................................................................................. 19 POPULATION & HOUSEHOLDS ................................................................................................................................ 19 EMPLOYMENT & COMMUTING .............................................................................................................................. -

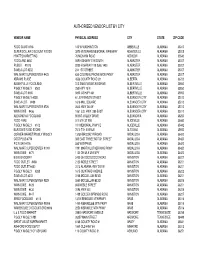

Alabama Vendor List.Xlsx

AUTHORIZED VENDOR LIST BY CITY VENDOR NAME PHYSICAL ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE FOOD GIANT #716 100 W WASHINGTON ABBEVILLE ALABAMA 36310 SUPER DOLLAR DISCOUNT FOODS 3970 VETERANS MEMORIAL PARKWAY ADAMSVILLE ALABAMA 35005 HYATT'S MARKET INC 70 MCHANN ROAD ADDISON ALABAMA 35540 FOODLAND #450 509 HIGHWAY 119 SOUTH ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 PUBLIX #1073 9200 HIGHWAY 119 Suite 1400 ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 SAVE-A-LOT #202 244 1ST STREET ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 WAL MART SUPERCENTER #423 630 COLONIAL PROMENADE PKWY ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 ABRAMS PLACE 4556 COUNTY ROAD 29 ALBERTA ALABAMA 36720 ALBERTVILLE FOODLAND 313 SAND MOUNTAIN DRIVE ALBERTVILLE ALABAMA 35950 PIGGLY WIGGLY #500 250 HWY 75 N ALBERTVILLE ALABAMA 35950 SAVE-A-LOT #165 5850 US HWY 431 ALBERTVILLE ALABAMA 35950 PIGGLY WIGGLY #238 61 JEFFERSON STREET ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 SAVE-A-LOT #489 1616 MILL SQUARE ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 WAL MART SUPERCENTER #726 2643 HWY 280 W ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 WINN DIXIE #456 1061 U.S. HWY. 280 EAST ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 ALEXANDRIA FOODLAND 85 BIG VALLEY DRIVE ALEXANDRIA ALABAMA 36250 FOOD FARE 517 5TH ST NW ALICEVILLE ALABAMA 35442 PIGGLY WIGGLY #102 101 MEMORIAL PKWY E ALICEVILLE ALABAMA 35442 BURTON'S FOOD STORE 7010 7TH AVENUE ALTOONA ALABAMA 35952 CORNER MARKET/PIGGLY WIGGLY 13759 BROOKLYN ROAD ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 COST PLUS #774 305 EAST THREE NOTCH STREET ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 PIC N SAV #776 550 W BYPASS ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 WAL MART SUPERCENTER #1091 1991 MARTIN LUTHER KING PKWY ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 WINN DIXIE -

Mcdonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1994 Small Fry, Big Spender: McDonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985 Kathleen D. Toerpe Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Toerpe, Kathleen D., "Small Fry, Big Spender: McDonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985" (1994). Dissertations. 3457. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3457 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1994 Kathleen D. Toerpe LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SMALL FRY, BIG SPENDER: MCDONALD'S AND THE RISE OF A CHILDREN'S CONSUMER CULTURE, 1955-1985 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY KATHLEEN D. TOERPE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY, 1994 Copyright by Kathleen D. Toerpe, 1994 All rights reserved ) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank McDonald's Corporation for permitting me research access to their archives, to an extent wider than originally anticipated. Particularly, I thank McDonald's Archivist, Helen Farrell, not only for sorting through the material with me, but also for her candid insight in discussing McDonald's past. My Director, Lew Erenberg, and my Committee members, Susan Hirsch and Pat Mooney-Melvin, have helped to shape the project from its inception and, throughout, have challenged me to hone my interpretation of McDonald's role in American culture. -

Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies

FSRG Publication Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies edited by Kyle W. Stiegert and Dong Hwan Kim FSRG Publication, November 2009 FSRG Publication Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies edited by Kyle W. Stiegert Dong Hwan Kim November 2009 Kyle Stiegert [email protected] The authors thank Kate Hook for her editorial assistance. Any mistakes are those of the authors. Comments are encouraged. Food System Research Group Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics University of Wisconsin-Madison http://www.aae.wisc.edu/fsrg/ All views, interpretations, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this document are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the supporting or cooperating organizations. Copyright © by the authors. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for noncommercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. ii Chapter 7: Food Retailing in the United States: History, Trends, Perspectives Kyle W. Stiegert and Vardges Hovhannisyan 1. INTRODUCTION: FOOD RETAILING: 1850-1990 Before the introduction of supermarkets, fast food outlets, supercenters, and hypermarts, various other food retailing formats operated successfully in the US. During the latter half of the 19th century, the chain store began its rise to dominance as grocery retailing format. The chain grocery store began in 1859 when George Huntington Hartford and George Gilman founded The Great American Tea Company, which later came to be named The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (Adelman, 1959). The typical chain store was 45 to 55 square meters, containing a relatively limited assortment of goods. -

Retail Scene Report

GFSI CONFERENCE 2020 – DISCOVERY TOURS 25th February | Seattle, USA Retail Scene Report Seattle, Washington State & America’s Pacific Northwest 19 The Consumer Goods Forum GFSI CONFERENCE 2020 – DISCOVERY TOURS 25th February | Seattle, USA Retail Scene Report Seattle, Washington State & America’s Pacific Northwest FEBRUARY 2020 Kantar Consulting for The Consumer Goods Forum’s GFSI Conference 2020 20 The Consumer Goods Forum GFSI CONFERENCE 2020 – DISCOVERY TOURS 25th February | Seattle, USA Contents Seattle, Washington State & America’s Pacific Northwest .............. 22 Food Retail in the Pacific Northwest ........................................................ 24 Supercenters & Warehouse Clubs ........................................................ 27 Supermarkets & Convenience Stores .................................................. 29 Full-Service Supermarkets .................................................................. 29 Value/Private-Label Supermarkets ................................................ 32 Convenience Stores ................................................................................ 34 Food Safety in America & Washington State ......................................... 35 The US Federal Government & Agencies ........................................... 35 Washington State Food Safety ................................................................ 36 City, Town, & Local Food Safety ............................................................ 37 Conclusions ........................................................................................................ -

State of the Chains, 2020

www.nycfuture.org DECEMBER 2020 STATE OF THE CHAINS, 2020 Our thirteenth annual ranking of national retailers in New York City finds by far the largest overall decline in the number of chain stores, and the third consecutive year-over-year drop in national retailer locations. The year was marked by unprecedented economic volatility across all sectors, and within all boroughs, as the national retail market experienced unprecedented contraction as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak and subsequent shutdowns and store closures. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 SIDEBAR: WHERE THE CHANGE IS OCCURRING 9 NEW YORK CITY’S LARGEST NATIONAL RETAILERS, 2020 11 NATIONAL RETAILER GROWTH BY INDUSTRY CATEGORY, 2019-2020 23 NATIONAL RETAILERS IN NYC BY ZIP CODE 24 MANHATTAN 29 BROOKLYN 32 This report was written by Marco Torres and edited by Charles Shaviro, Eli Dvorkin, and Jonathan Bowles. QUEENS 34 BRONX 37 Center for an Urban Future (CUF) is a leading New York STATEN ISLAND 38 City–based think tank that generates smart and sustainable public policies to reduce inequality, increase economic mobility, and grow the economy. General operating support for the Center for an Urban Future has been provided by The Clark Foundation and the Bernard F. and Alva B. Gimbel Foundation. CUF is also grateful for support from Fisher Brothers for the Middle Class Jobs Project. Executive Director: Jonathan Bowles Editorial & Policy Director: Eli Dvorkin Associate Editor: Laird Gallagher Data Researcher: Charles Shaviro Events & Operations Manager: Stephanie Arevalo Board of Directors: Gifford Miller (Chairman), Michael Connor (Vice Chair), Max Neukirchen (Treasurer), John H. Alschuler, Margaret Anadu, Jonathan Bowles, Russell Dubner, Lisa Gomez, Jalak Jobanputra, Kyle Kimball, David Lebenstein, Eric S. -

Business Overview

Navigating the Supermarket Channel -West Coast US 1 John Rand, SVP October 2016 Regional Grocery Forum - West © Kantar Retail 2016 2 Copyright © Kantar Retail 2016. All Rights Reserved. 501 Boylston St., Suite 6101, Boston, MA 02116 T: +1 (617) 912 2828 [email protected] No part of this material may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without the express written permission of Kantar Retail. The printing of any copies for backup is also strictly prohibited. Disclaimers The analyses and conclusions presented in this seminar represent the opinions of Kantar Retail. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the retailer(s) under discussion. This seminar is not endorsed or otherwise supported by the management of any of the companies covered during the course of the workshop or within the following slides. © Kantar Retail 2016 3 1 Exploring the West Coast Retail Landscape 2 The Albertsons Companies 3 Zooming In: Regional Focus © Kantar Retail 2016 Retailer Overview 4 Kroger and WinCo leading the race in sales growth rate KR Top West Supermarket Retailers Sales (USD billions) Square Footage (millions) % of West Totals US CAGR Rank CAGR CAGR CAGR 2016E 2016E Retailer 2011 2016E 2021E ('16E- 2011 2016E 2021E 2016E ('11-'16E) ('11-'16E) ('16E-'21E) Sales Sq Ft '21E) Sales 1 Kroger $84.1 $112.6 $140.0 6.0% 4.5% 143.9 171.0 179.3 3.5% 1.0% -

Think F Orward

AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2010 THINK FORWARD IN A RACE WITH CHANGE Retail is being hit with a wave of game-changing technology in the form of more than 9 million smartphones. As the act of shopping undergoes sweeping transformation, we will experience more change in the next five years than we have in the past forty. A STATE OF THE INDUSTRY REPORT FROM TABLEOFCONTENTS 3A MOBILIZINGFORTHEFUTURE Retailers face pressure to invest in digital, but not at the expense of brick-and-mortar. 6A SHARETHIS:IT’SNOTABOUTTHETECHNOLOGY Retailers need to worry less about offering the latest widget in favor of learning more about how consumers are connecting. 8A THEPARENTTRIBE:MILLENNIALS The 18- to 29-year-old consumer segment includes tech-savvy, community-centered parents. 10A PUTTINGOURHEADSINTHECLOUD Companies need to know where and how to connect with shoppers in the “cloud” of Web-based retailers. 12A FOOD.IT’SEVERYWHERE Food is the go-to category for driving productivity and shopper frequency. 14A THETIMEHASCOMETORE-IMAGINETHESTORE Technology trends are set to alter shopping experiences. 16A PREDICTIONS How technology will affect customer service, the physical store and brand experiences. 18A THEFUTURE:HOWTOGETTHEREFROMHERE What needs to be done now and in the mid-term to prepare for the future. 20A THECHAINSTOREAGETOP100 A comprehensive list of the 100 largest retailers in the United States. 26A INDEX An alphabetical listing of the 100 largest retailers. 28A LargestRetailersbyTotalNumberofStores Fastest-GrowingStoreCounts 29A HighestProductivityperStore RemarkableRecoveries HighestNetIncome 30A Top20RestaurantChains 31A Top20RestaurantChainsbyTotalNumberofU.S.Units Top20RestaurantChainsbyGrowthinTotalNumberofU.S.Units 32A ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Snap a picture of each QR code to see where it takes you online. If your mobile phone needs a code reader, download one at http://scancode.mobi/reader 2A chainstoreage.com August/september 2010 State of the Industry MOBILIZINGFORTHEFUTURE Retailers face pressure at both ends. -

Oregon Redemption Centers Albany Beaverton

Oregon Redemption Centers and Associated Retailers (5,000 or more sq ft in size) ZONE 1 ZONE 2 EXEMPT** DEALER REDEMPTION CENTERS*** FULL SERVICE PARTICIPATING RETAILERS PARTICIPATING RETAILERS (accept 144 containers) (accept 24 containers) REDEMPTION CENTERS (accept 0 containers) (accept 24 containers) 0 - 2.0 miles radius Albany from redemption center No Zone 2 Zone 1 No Zone 2141 Santiam Hwy SE Albany Grocery Outlet Albany East Liquor Store 1103 ALOHA 1950 14th Ave SE 2530 Pacific Blvd SE Albertsons #3557 approved 6/18/2015 Big Lots #4660 Dollar Tree #1508 6055 SW 185th 2000 14th Ave SE, Ste 102 1307 Waverly Dr SE Bi-Mart #606 Lowe's #3057 BEAVERTON 2272 Santiam Hwy 1300 9th Ave SE Fred Meyer #482 Costco #0682 15995 SW Walker Rd 3130 Killdeer Ave SE Fred Meyer #005 CANBY 2500 Santiam Blvd Fred Meyer #651 North Albany Market 1401 SE 1st Ave 621 NE Hickory Rite Aid #5365 Safeway #2604 1235 Waverly Dr SE 1051 SW 1st Ave Safeway #1659 1990 14th Ave SE CLACKAMAS Target #T609 Fred Meyer #063 2255 14th Ave SE 16301 SE 82nd Dr Walgreens #6530 1700 Pacific Blvd SE DALLAS Walmart #5396 Safeway #4404 1330 Goldfish Farm SE 138 W Ellendale Ave Wheeler Dealer 1740 SE Geary St EUGENE Winco Foods Fred Meyer #325 (Santa Clara) 3100 Pacific Blvd SE 60 Division St 0 - 2.0 miles radius 2.01 - 2.8 miles radius Beaverton from redemption center from redemption center Either Zone FLORENCE 9307 SW Beaverton-Hillsdale Hwy Albertsons #505 99 Ranch Cost Plus World Market #6060 Fred Meyer #464 5415 SW Beaverton Hillsdale Hwy 8155 SW Hall Blvd 10108 SW Washington -

2011 1.68 Mb

AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2011 Around the world, resurgent retail is inspiring the industry with creativity and challenging traditional ways of doing business. The store is evolving into a fluid idea that fits the mobile, global customer in search of new experiences to share. A STATE OF THE INDUSTRY REPORT FROM Table of Contents Vibrancy, creativity and optimism 3A Domestic and foreign chain store openings aggressive throughout 2011. The necessity for passion, daring and breaking with the past. Increased momentum, willingness to change 6A Technological creativity, social engagement, rethinking square footage. Adapting to the changed consumer 8A More shopping shifts to online, the dominance of deals, going to the city. Different values and tastes 10A The industry looks around the world for opportunity, embraces sustainability, finds room for super-specialty concepts. Breakout creativity 12A Brands add excitement and drama to routine transactions. Rethinking shops and shopping 13A Traditions return, as goods get delivered to the door and heritage brands gain young audiences. A sophisticated approach to digital 14A Improved digital strategies coupled with exciting design drive demand. Engaging and listening 16A Business is devoting more energy to keeping up with customers and learning their preferences. International influence 18A Innovative projects from around the world inspire the industry. Secrets to long-term success 19A Be part of the culture, expand wisely and love the business. The Chain Store Age Top 100 Buried Treasures 20A A comprehensive list of the 100 largest 30A Top 10 brands within Top 100 companies retailers in the United States. Index Money Makers 28A An alphabetical listing of the 100 31A Top 20 retailers based on net income largest retailers.