Front Matter Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PACIFIC’ Coupling Rods Fitted to Tornado at Darlington Locomotive Works

60163 Tornado 60163 Tornado 60163 Tornado THE A1 STEAM LOCOMOTIVE TRUST Registered Office, All Enquiries: Darlington Locomotive Works, Hopetown Lane, Darlington DL3 6RQ Hotline Answerphone: 01325 4 60163 E-mail: [email protected] Internet address: www.a1steam.com PRESS INFORMATION – PRESS INFORMATION - PRESS INFORMATION PR04/04 Monday 4 October 2004 MAJOR STEP FORWARD AS NEW STEAM LOCOMOTIVE BECOMES A ‘PACIFIC’ Coupling rods fitted to Tornado at Darlington Locomotive Works The A1 Steam Locomotive Trust, the registered charity that is building the first new mainline steam locomotive in Britain for over 40 years, today announced that No. 60163 Tornado is now a Pacific following the fitting of all four coupling rods to its six 6ft8in driving wheels (the name Pacific refers to the 4-6-2 wheel arrangement under the Whyte Notation of steam locomotive wheel arrangements) which now rotate freely together for the first time. Each of the four 7ft 6in rods weighs around two hundredweight and after forging, extensive machining and heat treatment, the four cost around £22,000 to manufacture. These rods are vital components within the £150,000 valve gear and motion assemblies, which are now the focus of work on Tornado at the Trust’s Darlington Locomotive Works. The Trust has also started work on the fitting of the rest of the outside motion. The bushes for the connecting rods are currently being machined at Ian Howitt Ltd, Wakefield and one side of the locomotive has now been fitted with a mock-up of parts of its valve gear. This is to enable accurate measurements to be taken to set the length of the eccentric rod as the traditional method of heating the rod to stretch/shrink it used when the original Peppercorn A1s were built in 1948/9 is no longer recommended as it can affect the rod’s metallurgical properties. -

The Unauthorised History of ASTER LOCOMOTIVES THAT CHANGED the LIVE STEAM SCENE

The Unauthorised History of ASTER LOCOMOTIVES THAT CHANGED THE LIVE STEAM SCENE fredlub |SNCF231E | 8 februari 2021 1 Content 1 Content ................................................................................................................................ 2 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 3 1975 - 1985 .......................................................................................................................... 6 Southern Railway Schools Class .................................................................................................................... 6 JNR 8550 .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 V&T RR Reno ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Old Faithful ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Shay Class B ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 JNR C12 ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 PLM 231A ..................................................................................................................................................... -

The A1steam Locomotive Trust Tornado to Be

60163 Tornado 60163 Tornado 60163 Tornado THE A1 STEAM LOCOMOTIVE TRUST Registered Office, All Enquiries: Darlington Locomotive Works, Hopetown Lane, Darlington DL3 6RQ Hotline Answerphone: 01325 4 60163 E-mail: [email protected] Internet address: www.a1steam.com PRESS INFORMATION – PRESS INFORMATION - PRESS INFORMATION PR05/04 Sunday 17 October 2004 TORNADO TO BE COMPLETED IN THREE YEARS Coal fired 60163 in steam by end of 2007 and on mainline in 2008 The A1 Steam Locomotive Trust, the registered charity that is building the first new mainline steam locomotive in Britain for over 40 years at a cost of over £2m, today announced that No. 60163 Tornado is to be completed by the end of 2007 and will be running on the mainline in 2008. The announcement follows a successful 11th Annual Convention attended by around 200 supporters at the Trust’s Darlington Locomotive Works on Saturday 9th October where No. 60163 Tornado is under construction. Having just fitted the coupling rods to No. 60163 Tornado, the Trust rotated the six 6ft8in driving wheels together on the incomplete locomotive for the first time in public at the Convention. The Trust also unveiled several significant new components for Tornado including other valve gear and motion components ready for fitting to the locomotive. The following key announcements were made at the Convention: 1. Following meetings with financial institutions the Trust’s strategy has been changed to reflect their requirement for supporting us 2. Having raised and spent over £1m on Tornado to-date, around £1m is now required to complete the locomotive 3. -

The Steam Locomotive Table, V1

The Steam Locomotive Table, v1 If you’re reading this; you either like steam trains, or want to know more about them. Hopefully, either way, I can scratch your itch with this; a set of randomizer/dice-roll tables of my own making; as inspired by some similar tables for tanks and aircrafts. Bear with me, I know not everyone knows the things I do, and I sure know I don’t know a lot of things other train enthusiasts do; but hopefully the descriptions and examples will be enough to get anyone through this smoothly. To begin, you’ll either want a bunch of dice or any online dice-rolling/number generating site (or just pick at your own whim); and somewhere or something to keep track of the details. These tables will give details of a presumed (roughly) standard steam locomotive. No sentinels or other engines with vertical boilers; no climax, shay, etc specially driven locomotives; are considered for this listing as they can change many of the fundamental details of an engine. Go in expecting to make the likes of mainline, branchline, dockyard, etc engines; not the likes of experiments like Bulleid’s Leader or specific industry engines like the aforementioned logging shays. Some dice rolls will have uneven distribution, such as “1-4, and 5-6”. Typically this means that the less likely detail is also one that is/was significantly less common in real life, or significantly more complex to depict. For clarity sake examples will be linked, but you’re always encouraged to look up more as you would like or feel necessary. -

Union Pacific 844 4-8-4 FEF “Northern”

True Sound Project for Zimo Sounds designed by Heinz Daeppen US Steam Page 1 Version 160328 Union Pacific 844 4-8-4 FEF “Northern” The Prototype The category FEF locomotives of the Union Pacific Railroad (UP), also known as class 800, are steam locomotives with the wheel arrangement 2'D2 '(Northern). In the total of 45 locomotives, there are three series of delivery or subclasses FEF 1 FEF 2 and FEF-3, where the FEF-2 and -3 differ in driving axels and cylinder diameter to the FEF-1. The last locomotive of this series, no. 844, was the last steam locomotive built for UP. It was never taken out of service and is kept operational by the UP today. In the late 1930s, the pulling loads on train operations were so large that the 2'D1 locomotives Class 7000 reached its limits. After the failure of such a locomotive, which happened to be pulling a train containing the official car of the US President, ALCO was commissioned to build a stronger engine, which could pull 20 coaches with 90 mph (145 km/h) on the flat. The first 20 locomotives were delivered 1937. They got the numbers 800-819 and the name FEF, which stood for "four-eight-four" (the wheel arrangement 4-8-4 in the Whyte notation). They had a driving wheels of 77 inches (1956 mm). The first driving axel was displaced laterally, so that despite a solid wheelbase of 6.7 m the locomotive could still handle the same radius curves . Despite the size of the locomotives only two cylinders were used, as was almost always common in the United States. -

Factors That Affect Health & Safety Are So Prominent a Part of Modern Living

Vol 22 No 143 THE EMAIL EDITION November 2005 THE BULLETIN For the WIRED members of the Model Railway Society of Ireland in its forty-second year Head of steam In the continental and US sectors, where RTR tends to be more dominant, investment risk is high but for different Happily the Doolan/ 6026 “debate” in the last issue did not reasons. Production numbers are greater than in the Britain result in satisfaction at dawn by means of pistols, swords or but locally, continental and US enthusiasts are in a minority. even brass pannier tanks so perhaps it is safe to consider Anyone wishing to up-grade might find disposal of his current locomotive model costs a little further. The proliferation of fleet an expensive exercise – a simple matter of supply and types, modifications, sub classes, design variants and demand. liveries now so evident in OO/HO sectors of the RTR There is no advantage in starting in a “war of the gauges” but market stands in stark contrast to the meagre offerings by there is merit in trying to see why other scales are attractive the Hornby Dublo/ Triang combination in days of yore. to other enthusiasts. In so doing, it might be instructive to Dissatisfaction with their limited model ranges spawned a discover where and why others see value instead of excess. taste for something different in a growing hobby. White metal, brass sheet and plastic based kits provided the Apart from the inherent advantages of 7mm mentioned by means of expanding and improving the fleet for those who 6026, those working in this scale tend to spend more of their wished to stay with British prototypes. -

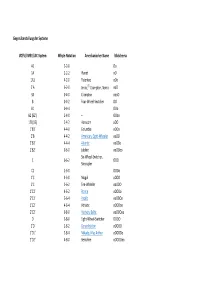

Gegenüberstellung Der Systeme VDEV/VMEV/UIC-System Whyte-Notation Amerikanischer Name Bildschema A1 2-2-0 Oo 1A 2-2-2 Planet Oo

Gegenüberstellung der Systeme VDEV/VMEV/UIC-System Whyte-Notation Amerikanischer Name Bildschema A1 2-2-0 Oo 1A 2-2-2 Planet oO 1A1 4-2-0 Patentee oOo 2’A 6-2-0 Jervis,[3] Crampton, Norris ooO 3A 0-4-0 Crampton oooO B 0-4-2 Four-Wheel-Switcher OO B1 0-4-4 OOo B2 (B2’) 2-4-0 – OOoo 1’B (1B) 2-4-2 Hanscom oOO 1’B1’ 4-4-0 Columbia oOOo 2’B 4-4-2 American, Eight-Wheeler ooOO 2’B1’ 4-4-4 Atlantic ooOOo 2’B2’ 0-6-0 Jubilee ooOOoo Six-Wheel-Switcher, C 0-6-2 OOO Sixcoupler C1 2-6-0 OOOo 1’C 4-6-0 Mogul oOOO 2’C 2-6-2 Ten-Wheeler ooOOO 1’C1’ 4-6-2 Prairie oOOOo 2’C1’ 2-6-4 Pacific ooOOOo 1’C2’ 4-6-4 Adriatic oOOOoo 2’C2’ 0-8-0 Hudson, Baltic ooOOOoo D 2-8-0 Eight-Wheel-Switcher OOOO 1’D 2-8-2 Consolidation oOOOO 1’D1’ 2-8-4 Mikado, Mac Arthur oOOOOo 1’D2’ 4-8-0 Berkshire oOOOOoo 2’D 4-8-2 Twelve-Wheeler, Mastodon ooOOOO 2’D1’ 4-8-4 Mountain, Mohawk (NYC) ooOOOOo Northern, Niagara (NYC), 2’D2’ 0-10-0 ooOOOOoo Wyoming E 0-10-2 Ten-Wheel Switcher OOOOO E1’ 2-10-0 Union OOOOOo 1’E 4-10-0 Decapod oOOOOO 2’E 2-10-2 Mastodon ooOOOOO 1’E1’ 2-10-4 Santa Fé oOOOOOo 1’E2’ 4-10-2 Texas oOOOOOoo Texas, Southern Pacific, 2’E1’ 2-12-0 ooOOOOOo Overland 1’F 2-12-2 Centipede oOOOOOO 1’F1’ 4-12-2 Javanic oOOOOOOo ooOOOOOO 2’F1’ 0-6-6-0 Union Pacific o C’C 2-6-6-0 Erie (Gelenklok) OOO OOO (1’C)C 2-6-6-2 namenlos (Gelenklok) oOOO OOO Gelenk Mogul (SP), Prairie (1’C)C1’ 2-6-6-4 oOOO OOOo Articulated (ATSF) oOOO (1’C)C2’ 4-6-6-4 namenlos (Gelenklok) OOOoo ooOOO (2’C)C2’ 2-6-6-6 Challenger (Gelenklok) OOOoo oOOO (1’C)C3’ 0-8-8-0 Allegheny (Gelenklok) OOOooo OOOO D’D -

LEGO Trains Reference - Texas Brick Railroad, 2021

LEGO Trains Reference - Texas Brick Railroad, 2021 LEGO Trains Glossary Ballast - The gravel, rocks, sand and other material laid under railroad track, which provides stability and drainage to the track. For LEGO trains, this is usually done with layers of plates and tiles under the track pieces. Also “ballasting track” - building LEGO tracks with such pieces. LEGO train builders sometimes include railroad ties when talking about ballasting. [Figure 2] Benchwork - Tables, usually custom-built to specific dimensions, on which a layout is displayed. Buffer - Shock-absorbing devices mounted on the ends of railcars, usually one in each corner, which maintain spacing between coupled railway cars. These are common in European trains but rare in North American trains, which tend to use rigid couplers. Buffers are attached to a transverse structure across the end of the car called the buffer beam. (see Bricklink part 29085c01 and its variants) [Figure 3] Buffer Stop - A device used to keep a train from going past the end of the track. These may involve buffers similar to those found on train cars, or other shock-absorbing mechanisms to slow down a train. Also called bumpers, bumper posts, or stopblocks. [Figure 4] Engine House - A building used to store and service locomotives. Sometimes built in a circular/semicircular shape called a roundhouse, with a turntable in the center to position and turn around engines. [Figure 5] Hand of God / Big Hand From the Sky - When you have to use your hand to pick up or adjust your train, couple/decouple cars, or operate other functions like switches. -

The First Garratt Locomotive in the Netherlands

The first Garratt locomotive in the Netherlands By H. Brunner ME Translation ©2015 by René F. Vink, Netherlands In this article1 the reasons are mentioned that made the Limburg Tramway Co Ltd decide to purchase a "Garratt" locomotive. Furthermore a description is given of the acquired locomotive. General. In December 1931 a "Garratt" locomotive of 71.5 t [70.4 long ton] service weight was putinto service by the Limburg Tramway Co Ltd on her 26 km [16 mi] long line Maastricht-Vaals (fig. 1). Fig. 1. The Garratt locomotive In 1909 the Australian H.W. Garratt († 1913) obtained the patents on his engine type, with which the boiler was freely and completely accessible located on a frame that rested with pivots on a bogie each of which contained a separate locomotive engine. By locating the supply bunkers for water and coal on the bogie units, he diminished the tendency of the latter to rotate around their horizontal centers of gravitation at higher speeds as a consequence of the not fully counter balanced reciprocating masses of the components of the motion. Thus they contribute to the riding stability of the locomotive. He could increase the evaporative ability of the boiler almost at will because the dimensions of the boiler, the fire grate and the ash pan were no longer restricted by the tight dimensions and unfavourable restrictions of coupled wheels and water tanks. 1 This is a translation of the article that appeared in issue 35 of the Dutch magazine "De Ingenieur" (The Mechanical Engineer) in 1932. Some considerations apply to this translation - I followed the UK English spelling. -

UP Class 4000 “Bigboy”

True Sound Project for Zimo Sounds designed by Heinz Daeppen US Steam Page 1 Version 150403 UP Class 4000 “BigBoy” Prototype information The class 4000 of the Union Pacific Railroad (UP), known as the Big Boy, was one of the largest and most powerful steam locomotives worldwide. A total of 25 units of this type were built by the American Locomotive Company (ALCO), 20 in the year 1941 and five in the year 1944. It was designed by a team led by Otto Jabelmann, who had already designed the Big Boy predecessor, the class 3900. (The Manufacturer's designation was Challenger with the wheel arrangement (2'C) C2 '). An unknown employee of the ALCO works came up with the name Big Boy, which he wrote with chalk on the smoke chamber. The name came into use quickly for the locomotives of the 4000 class. The locomotives were specified by the Union Pacific Railroad especially for the freight duty in the Rocky Mountains, to eliminate the need for labor-intensive double heading and helper operations over the continental divide. The most difficult section on the Union Pacific transcontinental line of was the long climb over Sherman Hill (Albany County, Wyoming) south of Ames Monument, with a maximum gradient of 1.55%. The new locomotives needed to pull 3.600 short tons (about 3.300 t) up this gradient, but also had to be fast enough to cover the whole distance between Cheyenne (Wyoming) and Ogden (Utah) without changing locomotives. The performance requirements showed the need for an articulated locomotive with the wheel arrangement (2'd) D2 ' (Whyte notation: 4-8-8-4 ). -

Whyte Classification of Steam Locomotive Wheel Arrangements

Lindsay & District Model Railroaders P.O. Box 452, Lindsay, ON, K9V 4S5 Email: [email protected] http://www.ldmr.org Steam Locomotive Wheel Arrangements Whyte-Notation American name picture scheme 2-2-0 Planet oO 2-2-2 Patentee oOo 4-2-0 Crampton, Norris ooO 6-2-0 Crampton oooO 0-4-0 Four-Wheel-Switcher OO 2-4-0 Hanscom oOO 2-4-2 Columbia oOOo 4-4-0 American, Eight-Wheeler ooOO 4-4-2 Atlantic ooOOo 4-4-4 Jubilee ooOOoo 0-6-0 Six-Wheel-Switcher OOO 2-6-0 Mogul oOOO 4-6-0 Ten-Wheeler ooOOO 2-6-2 Prairie oOOOo 4-6-2 Pacific ooOOOo 2-6-4 Adriatic oOOOoo 4-6-4 Hudson, Baltic ooOOOoo 0-8-0 Eight-Wheel-Switcher OOOO 2-8-0 Consolidation oOOOO 2-8-2 Mikado, Mac Arthur oOOOOo 2-8-4 Berkshire oOOOOoo 4-8-0 Twelve-Wheeler, Mastodon ooOOOO 4-8-2 Mountain, Mohawk (NYC) ooOOOOo 4-8-4 General Service (SP), Golden State (SP), Northern, Niagara (NYC), Wyoming ooOOOOoo 0-10-0 Ten-Wheel Switcher OOOOO 0-10-2 Union OOOOOo 2-10-0 Decapod oOOOOO 4-10-0 Mastodon ooOOOOO 2-10-2 Santa Fe oOOOOOo 2-10-4 Texas oOOOOOoo 4-10-2 Texas, Southern Pacific, Overland ooOOOOOo 2-12-0 Centipede oOOOOOO 2-12-2 Javanic oOOOOOOo 4-12-2 Union Pacific ooOOOOOOo 0-6-6-0 Erie (Mallet-Lok) OOO OOO 2-6-6-0 nameless (Mallet-Lok) oOOO OOO 2-6-6-2 Mallet Mogul (SP), Prairie Mallet (ATSF) oOOO OOOo 2-6-6-4 nameless (Mallet-Lok) oOOO OOOoo 4-6-6-4 Challenger (Mallet-Lok) ooOOO OOOoo 2-6-6-6 Allegheny (Mallet-Lok) oOOO OOOooo 0-8-8-0 Angus (Mallet-Lok) OOOO OOOO 2-8-8-0 Bullmoose (Mallet-Lok) oOOOO OOOO 2-8-8-2 Chesapeake, Mallet consolidation (Mallet-Lok) oOOOO OOOOo 2-8-8-4 Yellowstone (Mallet-Lok) oOOOO OOOOoo 4-8-8-2 Articulated consolidation (Mallet-Lok) ooOOOO OOOOo 4-8-8-4 Big Boy (Mallet-Lok) ooOOOO OOOOoo 2-10-10-2 Virginian (Mallet-Lok) oOOOOO OOOOOo 4-6-2 + 2-6-4 Double Pacific (Garratt-Lok) ooOOOo oOOOoo 4-8-2 + 2-8-4 Double Mountain (Garratt-Lok) ooOOOOo oOOOOoo Page 1 of 1 . -

Forney from Accucraft a Development of the Much-Modded Ruby from the US – a Gardenrail Review

REVIEWS G SCALE Forney from Accucraft A development of the much-modded Ruby from the US – a GardenRail review. ccucraft US started live-steam model making with the eccentrics are obvious ‘carry over’ components. The cylinders now oft maligned but reasonably priced ‘Ruby,’ and from the feature a nice crosshead, a characteristic bound to please many. The Astart this little locomotive has been the basis for many original Horowitz design was somewhat hamstrung by the small conversions. Mark Horowitz, the designer of the original Ruby, cylinders which needed rather more than 30psi to generate power to believed its whole raison d’être was to be regularly reworked by approach that of a Roundhouse ‘Sammie’. those of a kit-bashing nature. The cab has been much improved and it is no longer the It is one of these conversions that encouraged the production of invective-invoking and tantrum-producing lift-off item that was this recently introduced ‘Classic Range’ model. Forney locomotives possibly the single most frustrating part ever attached to a model. came in a multitude of styles, shapes and sizes. All featured a very The new roof lifts and tips to one side while the main cab body large cab and an under-cab truck, while some had a forward pony has a solid bolt-down fixing to the footplate. With the cab open, truck and some did not. access to all the usual service items is pretty much the same as on a The original Forney design was patented by Matthias Forney in standard Accucraft UK live steam model – with a few exceptions.