Douglas-Fir Beetle Malcolm M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1 B.W. Kooi Groningen, The Netherlands 1983 1B.W. Kooi, On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow PhD-thesis, Mathematisch Instituut, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, The Netherlands (1983), Supported by ”Netherlands organization for the advancement of pure research” (Z.W.O.), project (63-57) 2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Prefaceandsummary.............................. 5 1.2 Definitionsandclassifications . .. 7 1.3 Constructionofbowsandarrows . .. 11 1.4 Mathematicalmodelling . 14 1.5 Formermathematicalmodels . 17 1.6 Ourmathematicalmodel. 20 1.7 Unitsofmeasurement.............................. 22 1.8 Varietyinarchery................................ 23 1.9 Qualitycoefficients ............................... 25 1.10 Comparison of different mathematical models . ...... 26 1.11 Comparison of the mechanical performance . ....... 28 2 Static deformation of the bow 33 2.1 Summary .................................... 33 2.2 Introduction................................... 33 2.3 Formulationoftheproblem . 34 2.4 Numerical solution of the equation of equilibrium . ......... 37 2.5 Somenumericalresults . 40 2.6 A model of a bow with 100% shooting efficiency . .. 50 2.7 Acknowledgement................................ 52 3 Mechanics of the bow and arrow 55 3.1 Summary .................................... 55 3.2 Introduction................................... 55 3.3 Equationsofmotion .............................. 57 3.4 Finitedifferenceequations . .. 62 3.5 Somenumericalresults . 68 3.6 On the behaviour of the normal force -

Psme 46 Douglas-Fir-Incense

PSME 46 DOUGLAS-FIR-INCENSE-CEDAR/PIPER'S OREGONGRAPE Pseudotsuga menziesii-Calocedrus decurrens/Berberis piperiana PSME-CADE27/BEPI2 (N=18; FS=18) Distribution. This Association occurs on the Applegate, Ashland, and Prospect Ranger Districts, Rogue River National Forest, and the Tiller and North Umpqua Ranger Districts, Umpqua National Forest. It may also occur on the Butte Falls Ranger District, Rogue River National Forest and adjacent Bureau of Land Management lands. Distinguishing Characteristics. This is a drier, cooler Douglas-fir association. White fir is frequently present, but with relatively low covers. Piper's Oregongrape and poison oak, dry site indicators, are also frequently present. Soils. Parent material is mostly schist, welded tuff, and basalt, with some andesite, diorite, and amphibolite. Average surface rock cover is 8 percent, with 8 percent gravel. Soils are generally deep, but may be moderately deep, with an average depth of greater than 40 inches. PSME 47 Environment. Elevation averages 3000 feet. Aspects vary. Slope averages 35 percent and ranges between 12 and 62 percent. Slope position ranges from the upper one-third of the slope down to the lower one-third of the slope. This Association may also occur on benches and narrow flats. Vegetation Composition and Structure. Total species richness is high for the Series, averaging 44 percent. The overstory is dominated by Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine, with sugar pine and incense-cedar common associates. Douglas-fir dominates the understory. Incense-cedar, white fir, and Pacific madrone frequently occur, generally with covers greater than 5 percent. Sugar pine is common. Frequently occurring shrubs include Piper's Oregongrape, baldhip rose, poison oak, creeping snowberry, and Pacific blackberry. -

DOUGLAS's Datasheet

DOUGLAS Page 1of 4 Family: PINACEAE (gymnosperm) Scientific name(s): Pseudotsuga menziesii Commercial restriction: no commercial restriction Note: Coming from North West of America, DOUGLAS FIR is often used for reaforestation in France and in Europe. Properties of european planted trees (young and with a rapid growth) which are mentionned in this sheet are different from those of the "Oregon pine" (old and with a slow growth) coming from its original growing area. WOOD DESCRIPTION LOG DESCRIPTION Color: pinkish brown Diameter: from 50 to 80 cm Sapwood: clearly demarcated Thickness of sapwood: from 5 to 10 cm Texture: medium Floats: pointless Grain: straight Log durability: low (must be treated) Interlocked grain: absent Note: Heartwood is pinkish brown with veins, the large sapwood is yellowish. Wood may show some resin pockets, sometimes of a great dimension. PHYSICAL PROPERTIES MECHANICAL AND ACOUSTIC PROPERTIES Physical and mechanical properties are based on mature heartwood specimens. These properties can vary greatly depending on origin and growth conditions. Mean Std dev. Mean Std dev. Specific gravity *: 0,54 0,04 Crushing strength *: 50 MPa 6 MPa Monnin hardness *: 3,2 0,8 Static bending strength *: 91 MPa 6 MPa Coeff. of volumetric shrinkage: 0,46 % 0,02 % Modulus of elasticity *: 16800 MPa 1550 MPa Total tangential shrinkage (TS): 6,9 % 1,2 % Total radial shrinkage (RS): 4,7 % 0,4 % (*: at 12% moisture content, with 1 MPa = 1 N/mm²) TS/RS ratio: 1,5 Fiber saturation point: 27 % Musical quality factor: 110,1 measured at 2971 Hz Stability: moderately stable NATURAL DURABILITY AND TREATABILITY Fungi and termite resistance refers to end-uses under temperate climate. -

Arthropod Diversity and Conservation in Old-Growth Northwest Forests'

AMER. ZOOL., 33:578-587 (1993) Arthropod Diversity and Conservation in Old-Growth mon et al., 1990; Hz Northwest Forests complex litter layer 1973; Lattin, 1990; JOHN D. LATTIN and other features Systematic Entomology Laboratory, Department of Entomology, Oregon State University, tural diversity of th Corvallis, Oregon 97331-2907 is reflected by the 14 found there (Lawtt SYNOPSIS. Old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest extend along the 1990; Parsons et a. e coastal region from southern Alaska to northern California and are com- While these old posed largely of conifer rather than hardwood tree species. Many of these ity over time and trees achieve great age (500-1,000 yr). Natural succession that follows product of sever: forest stand destruction normally takes over 100 years to reach the young through successioi mature forest stage. This succession may continue on into old-growth for (Lattin, 1990). Fire centuries. The changing structural complexity of the forest over time, and diseases, are combined with the many different plant species that characterize succes- bances. The prolot sion, results in an array of arthropod habitats. It is estimated that 6,000 a continually char arthropod species may be found in such forests—over 3,400 different ments and habitat species are known from a single 6,400 ha site in Oregon. Our knowledge (Southwood, 1977 of these species is still rudimentary and much additional work is needed Lawton, 1983). throughout this vast region. Many of these species play critical roles in arthropods have lx the dynamics of forest ecosystems. They are important in nutrient cycling, old-growth site, tt as herbivores, as natural predators and parasites of other arthropod spe- mental Forest (HJ cies. -

Western Larch, Which Is the Largest of the American Larches, Occurs Throughout the Forests of West- Ern Montana, Northern Idaho, and East- Ern Washington and Oregon

Forest An American Wood Service Western United States Department of Agriculture Larch FS-243 The spectacular western larch, which is the largest of the American larches, occurs throughout the forests of west- ern Montana, northern Idaho, and east- ern Washington and Oregon. Western larch wood ranks among the strongest of the softwoods. It is especially suited for construction purposes and is exten- sively used in the manufacture of lumber and plywood. The species has also been used for poles. Water-soluble gums, readily extracted from the wood chips, are used in the printing and pharmaceutical industries. F–522053 An American Wood Western Larch (Lark occidentalis Nutt.) David P. Lowery1 Distribution Western larch grows in the upper Co- lumbia River Basin of southeastern British Columbia, northeastern Wash- ington, northwest Montana, and north- ern and west-central Idaho. It also grows on the east slopes of the Cascade Mountains in Washington and north- central Oregon and in the Blue and Wallowa Mountains of southeast Wash- ington and northeast Oregon (fig. 1). Western larch grows best in the cool climates of mountain slopes and valleys on deep porous soils that may be grav- elly, sandy, or loamy in texture. The largest trees grow in western Montana and northern Idaho. Western larch characteristically occu- pies northerly exposures, valley bot- toms, benches, and rolling topography. It occurs at elevations of from 2,000 to 5,500 feet in the northern part of its range and up to 7,000 feet in the south- ern part of its range. The species some- times grows in nearly pure stands, but is most often found in association with other northern Rocky Mountain con- ifers. -

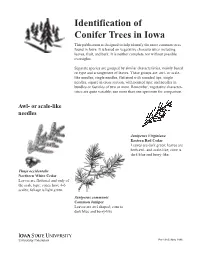

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes

Ornamental Horticulture Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes Bob Cain, Extension Forest Entomologist One-Seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) Description: One-seed juniper grows 20-30 feet high and is multistemmed. Its leaves are scalelike with finely toothed margins. One-seed cones are 1/4-1/2 inch long berrylike structures with a reddish brown to bluish hue. The cones or “berries” mature in one year and occur only on female trees. Male trees produce Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) pollen and appear brown in the late winter and spring compared to female trees. Description: The alligator juniper can grow up to 65 feet tall, and may grow to 5 feet in diameter. It resembles the one-seed juniper with its 1/4-1/2 inch long, berrylike structures and typical juniper foliage. Its most distinguishing feature is its bark, which is divided into squares that resemble alligator skin. Other Characteristics: • Ranges throughout the semiarid regions of the southern two-thirds of New Mexico, southeastern and central Arizona, and south into Mexico. Other Characteristics: • An American Forestry Association Champion • Scattered distribution through the southern recently burned in Tonto National Forest, Arizona. Rockies (mostly Arizona and New Mexico) It was 29 feet 7 inches in circumference, 57 feet • Usually a bushy appearance tall, and had a 57-foot crown. • Likes semiarid, rocky slopes • If cut down, this juniper can sprout from the stump. Uses: Uses: • Birds use the berries of the one-seed juniper as a • Alligator juniper is valuable to wildlife, but has source of winter food, while wildlife browse its only localized commercial value. -

Douglasfirdouglasfirfacts About

DouglasFirDouglasFirfacts about Douglas Fir, a distinctive North American tree growing in all states from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, is probably used for more Beams and Stringers as well as Posts and Timber grades include lumber and lumber product purposes than any other individual species Select Structural, Construction, Standard and Utility. Light Framing grown on the American Continent. lumber is divided into Select Structural, Construction, Standard, The total Douglas Fir sawtimber stand in the Western Woods Region is Utility, Economy, 1500f Industrial, and 1200f Industrial grades, estimated at 609 billion board feet. Douglas Fir lumber is used for all giving the user a broad selection from which to choose. purposes to which lumber is normally put - for residential building, light Factory lumber is graded according to the rules for all species, and and heavy construction, woodwork, boxes and crates, industrial usage, separated into Factory Select, No. 1 Shop, No. 2 Shop and No. 3 poles, ties and in the manufacture of specialty products. It is one of the Shop in 5/4 and thicker and into Inch Factory Select and No. 1 and volume woods of the Western Woods Region. No. 2 Shop in 4/4. Distribution Botanical Classification In the Western Douglas Fir is manufactured by a large number of Western Woods Douglas Fir was discovered and classified by botanist David Douglas in Woods Region, Region sawmills and is widely distributed throughout the United 1826. Botanically, it is not a true fir but a species distinct in itself known Douglas Fir trees States and foreign countries. Obtainable in straight car lots, it can as Pseudotsuga taxifolia. -

End Jointing of Laminated Veneer Lumber for Structural Use

End jointing of laminated veneer lumber for structural use J.A. Youngquist T.L. Laufenberg B.S. Bryant proprietary process for manufacturing extremely long Abstract lengths of the material both in panel widths and in LVL Laminated veneer lumber (LVL) materials rep- form. The proprietary process requires a substantial resent a design alternative for structural lumber users. capital investment, limiting production of LVL. If ex- The study of processing options for producing LVL in isting plywood facilities were adapted to processing of plywood manufacturing and glued-laminating facilities 5/8-inch- to 1-1/2-inch-thick panels, subsequent panel is of interest as this would allow existing production ripping and end jointing of the resultant structural equipment to be used. This study was conducted in three components could conceivably compete both in price and phases to assess the feasibility of using visually graded performance with the highest structural grades of lum- veneer to produce 8-foot LVL lengths which, when end ber. Herein lies the major concern of this study: Is it jointed, could be competitive with existing structural technically feasible to manufacture end-jointed LVL lumber products. Phase I evaluated panel-length from PLV panels made in conventional plywood 3/4-inch-thick LVL made from C- or D-grade 3/16-, 1/8-, presses? or 1/10-inch-thick veneer, and the effect of specimen width on flexural and tensile properties. Phase II evalu- An evaluation of the production and marketing ated the use of vertical and horizontal finger joints and feasibility of LVL products made from panel lengths scarfjoints to join 3/4-inch thicknesses of LVL. -

Current U.S. Forest Data and Maps

CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA AND MAPS Forest age FIA MapMaker CURRENT U.S. Forest ownership TPO Data FOREST DATA Timber harvest AND MAPS Urban influence Forest covertypes Top 10 species Return to FIA Home Return to FIA Home NEXT Productive unreserved forest area CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA (timberland) in the U.S. by region and AND MAPS stand age class, 2002 Return 120 Forests in the 100 South, where timber production West is highest, have 80 s the lowest average age. 60 Northern forests, predominantly Million acreMillion South hardwoods, are 40 of slightly older in average age and 20 Western forests have the largest North concentration of 0 older stands. 1-19 20-39 40-59 60-79 80-99 100- 120- 140- 160- 200- 240- 280- 320- 400+ 119 139 159 199 240 279 319 399 Stand-age Class (years) Return to FIA Home Source: National Report on Forest Resources NEXT CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA Forest ownership AND MAPS Return Eastern forests are predominantly private and western forests are predominantly public. Industrial forests are concentrated in Maine, the Lake States, the lower South and Pacific Northwest regions. Source: National Report on Forest Resources Return to FIA Home NEXT CURRENT U.S. Timber harvest by county FOREST DATA AND MAPS Return Timber harvests are concentrated in Maine, the Lake States, the lower South and Pacific Northwest regions. The South is the largest timber producing region in the country accounting for nearly 62% of all U.S. timber harvest. Source: National Report on Forest Resources Return to FIA Home NEXT CURRENT U.S. -

Slimline Standard Inswing Door WA8400 (Rev

Slimline Standard Inswing Door WA8400 (rev. 02.06.18) Copyright © 2018 Reveal Windows & Doors All rights reserved. No part of this manual may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission by Reveal Windows & Doors. Slimline Standard Inswing Door WA8400 (rev. 02.06.18) Slimline Standard Inswing Door WA8400 Section Contents Product Overview ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Hardware Options ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Glazing Options ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Wood Species .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Hardware Images ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Insects That Feed on Trees and Shrubs

INSECTS THAT FEED ON COLORADO TREES AND SHRUBS1 Whitney Cranshaw David Leatherman Boris Kondratieff Bulletin 506A TABLE OF CONTENTS DEFOLIATORS .................................................... 8 Leaf Feeding Caterpillars .............................................. 8 Cecropia Moth ................................................ 8 Polyphemus Moth ............................................. 9 Nevada Buck Moth ............................................. 9 Pandora Moth ............................................... 10 Io Moth .................................................... 10 Fall Webworm ............................................... 11 Tiger Moth ................................................. 12 American Dagger Moth ......................................... 13 Redhumped Caterpillar ......................................... 13 Achemon Sphinx ............................................. 14 Table 1. Common sphinx moths of Colorado .......................... 14 Douglas-fir Tussock Moth ....................................... 15 1. Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University Cooperative Extension etnomologist and associate professor, entomology; David Leatherman, entomologist, Colorado State Forest Service; Boris Kondratieff, associate professor, entomology. 8/93. ©Colorado State University Cooperative Extension. 1994. For more information, contact your county Cooperative Extension office. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture,