Ed 359 288 Title Institution Pub Date Note Available from Pub Type Edrs Price Descriptors Identifiers Abstract Document Resume U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

Westward Expansion and Indian Removal

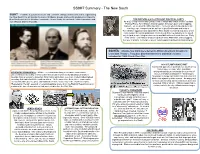

Unit 6: The New South SS8H7 Griffith-Georgia Studies THE BIG IDEA SS8H7: The student will evaluate key political, social, and economic changes that occurred in Georgia between 1877 and 1918. Evaluate- to make a judgment as to the worth or value of something; judge, assess Griffith-Georgia Studies SS8H7a SS8H7a: Evaluate the impact the Bourbon Triumvirate, Henry Grady, International Cotton Expositions, Tom Watson and the Populists, Rebecca Latimer Felton, The 1906 Race Riot, the Leo Frank Case, and the county unit system had on Georgia between 1877 and 1918 Evaluate- to make a judgment as to the worth or value of something; judge, assess Griffith-Georgia Studies Bourbon Triumvirate SS8H7a Bourbon Triumvirate- GA’s 3 most powerful politicians during the Post-Reconstruction Era. Brown They were… John B. Gordon Joseph E. Brown Alfred H. Colquitt Shared power between Colquitt the governor and senate seats from 1872-1890 Gordon Griffith-Georgia Studies John B. Gordon SS8H7a Father owned a coal mine and he worked there when the Civil war broke out. Gained notoriety in the war as a distinguished Confederate officer. Wounded 5 times Political leader Generally acknowledged as head of the Ku Klux Klan in GA Member of the Bourbon Triumvirate Served multiple terms in the U.S. Senate Governor of GA from 1886 to 1890 Griffith-Georgia Studies Joseph E. Brown SS8H7a Born in SC moved to GA Briefly attended Yale Became lawyer and businessman The Civil War governor of GA One of the most successful politicians in GA’s history. Member of the Bourbon Triumvirate Brown served as a U.S. -

1995 Annual Meeting Program

ACJS EXECUTIVE BOARD 1st VICE PRESIDENT PRESIDENT and PRESIDENT ELECT 2nd VICE PRESIDENT Harry Allen Jay Albanese Donna Hale San Jose State University Niagara University Shippensburg University Administration of Justice Political Scn/Crim Just Criminal Justice Dept San Jose, CA 95192 Niagara Univ, NY 14109 Shippensburg, PA 17257 SECRETARYjTREASURER IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT Marilyn Chandler Ford Francis Cullen Volusia County Branch Jail University of Cincinnati Caller Service Box 2865 Criminal Justice/Box 210389 Daytona Beach, FL 32120-2865 Cincinnati, OH 45221-0389 TRUSTEES AT lARGE Mittie Southerland Dorothy Taylor Alida Merlo Eastern Kentucky University University of Miami Westfield State College College of Law Enforcement Sociology Dept/Box 248164 Criminal Justice Dept Richmond, KY 40475 Miami, FL 33124-2208 Westfield, MA 01086 REGIONAL. TRUSTEES REGION 1 - NORTHEAST REGION 2 - SOUTHERN REGION 3 - MIDWEST Eva Buzawa Charles Fields Frank Horvath University of MA-Lowell Appalachian State University Michigan State University Lowell, MA 01854 Boone, NC 28608 East Lansing, MI 48824 REGION 4 - SOUTHWEST REGION 5 - WESTERN/PACIAC Mary Parker Frank Williams III University of Arkansas California State University Little Rock, AR 72204-1099 San Bernardino, CA 92407 PAST PRESIDENTS 1963-1964 Donald F McCall 1979-1980 Larry Bassi 1964-1965 Felix M Fabian 1980-1981 Harry More Jr 1965-1966 Arthur F Brandstatter 1981-1982 Robert G Culbertson 1966-1967 Richard 0 Hankey 1982-1983 Larry T Hoover 1967-1968 Robert Sheehan 1983-1984 Gilbert Bruns 1968-1969 -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

The Transformation of Noncitizen Detention in the United States

From Exclusion to State Violence: The Transformation of Noncitizen Detention in the United States and Its Implications in Arizona, 1891-present by Judith Irangika Dingatantrige Perera A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved March 2018 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Jack Schermerhorn, Chair Leah Sarat Julian Lim ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzes the transformation of noncitizen detention policy in the United States over the twentieth century. For much of that time, official policy remained disconnected from the reality of experiences for those subjected to the detention regime. However, once detention policy changed into its current form, disparities between policy and reality virtually disappeared. This work argues that since its inception in the late nineteenth century to its present manifestations, noncitizen detention policy transformed from a form of exclusion to a method of state-sponsored violence. A new periodization based on detention policy refocuses immigration enforcement into three eras: exclusion, humane, and violent. When official policy became state violence, the regime synchronized with noncitizen experiences in detention marked by pain, suffering, isolation, hopelessness, and death. This violent policy followed the era of humane detentions. From 1954 to 1981, during a time of supposedly benevolent national policies premised on a narrative against de facto detentions, Arizona, and the broader Southwest, continued to detain noncitizens while collecting revenue for housing such federal prisoners. Over time increasing detentions contributed to overcrowding. Those incarcerated naturally reacted against such conditions, where federal, state, and local prisoners coalesced to demand their humanity. Yet, when taxpayers ignored these pleas, an eclectic group of sheriffs, state and local politicians, and prison officials negotiated with federal prisoners, commodifying them for federal revenue. -

Thomas Hungerford

ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS FOR THOMAS HUNGERFORD OF HARTFORD AND NEW LONDON, CONN. AND HIS DESCENDANTS IN AMERICA By F. PHELPS LEACH Pitblished by F. PHELPS LEACH East Highgate, Vermont 1932 F"REI; PRESS PRINTING co.I BURLINGTOM1 VT, Copyright 1932 by F. PHELPS LEACH All rights reserved THE AUTHOR'S PREFACE The preparation of these additions and corrections for Thomas Hungerford of Hartford and New London, Conn., that I published in 1924, has been attended with no ordinary degree of perplexity and toil, on account of the imperfect and disordered condition of the records, and the necessity of resorting to various other sources for information. I have aimed at but two results-fullness and accuracy, but it is hardly to be expected that errors have been wholly avoided, and it is hoped that they are but few, and that they do not impair the usefulness of the work. I made two errors in my 1924 work which I have corrected in this, but the printers dropped type when they went to press, and were responsible for several. On page 14, in lines 35 and 38, they make the surname of the children of 5. Joseph Douglass7 Soule, Barnes instead of Soule. Mr. Soule married Mary Elizabeth Barnes. The first words that invite the eye in a book are the last written. When the preface is prepared the work is finished. Many lines in this volume are up-to-date, but the genealogy of the Hungerfords goes on. More great men of the name are to come. The logic of all genealogy contemplates the conclusion we confidently declare it is, that some day one of the descendants of this tribe will publish the 187 pages of manuscript of our English ancestors that I have before me. -

Ss8h7-Summary-New-South 2018

SS8H7 Summary - The New South SS8H7 Evaluate key political, social, and economic changes that occurred in Georgia during the New South Era. a.) Identify the ways individuals, groups, and events attempted to shape the New South; include the Bourbon Triumvirate, Henry Grady, International Cotton Exposition, and TOM WATSON and the POPULIST POLITICAL PARTY Tom Watson and the Populists. As a US Congressman and Senator from Georgia and leader of the Populists Political Party, Tom Watson helped support Georgia’s poor and struggling farmers. He created the RFD (Rural Free Delivery) which helped deliver US mail to people living in rural areas that helped build roads and bridges. Tom Watson opposed (was against) the New South movement and many of the conservative Democrat politicians. He believed that new industry in the south only helped people living in urban areas and did not benefit rural farmers. Early in his career Tom Watson tried to help both white AND black sharecroppers, but later in politics he became openly racist supporting disenfranchising blacks. SS8H7b Analyze how rights were denied to African-Americans through Jim Crow laws, Plessy v. Ferguson, disenfranchisement, and racial violence, including the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot. 1906 ATLANTA RACE RIOT Atlanta had gained a reputation as a southern city that prospered under white and black entrepreneurship as evident by the success of BOURBON TRIUMVIRATE - All three men had something in common: conservative Democrat Governors who embraced the New South movement by wanting to transform Alonzo Herndon and Booker T. Washington. Georgia from an economy based on King Cotton agriculture to a more modern industrialized Newspapers to spread racial fears and rumors of black men attacking white women. -

Saddam Expects Attack from U.S. in Near Future (AP) - Saddam Hussein Said Before Embarking on Hostilities

---------------- ~------- ---------- ~~ I VOL. XXIII NO. 42 WEDNESDAY I OCTOBER 31,1990 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY'S Saddam expects attack from U.S. in near future (AP) - Saddam Hussein said before embarking on hostilities. there is no timetable for ac Tuesday that Iraq was making He refused to comment publicly tion." final preparations for war and on a report the United States Fitzwater sought to dampen expected an attack within days plans to discuss a timetable fears that fighting was immi by the United States and its al with U.S. allies for a military nent. "The attitude at the lies. A U.S. senator said offensive. meeting was play it down - be President Bush's "patience is Secretary of State James calm." he said. wearing thin." Baker on Saturday will begin a The United States has more In the Persian Gulf, 10 weeklong visit to Arab and than 200,000 troops in the gulf American sailors died when a European countries to consult region and has announced steam pipe ruptured in the on future steps in the gulf, offi plans to send at least 100,000 boiler room of the USS Iwo cials said. The visit will include more. It is the largest U.S. mili Jima. And in Saudi Arabia, a a meeting with Soviet Foreign tary deployment since the Marine was killed in an acci Minister Eduard Shevardnadze. Vietnam War. dent while driving in the desert. Asked about the potential for Saddam summoned his mili · Bush discussed possible mili a U.S. military strike, White tary commanders to a meeting tary action against Iraq in a House spokesman Marlin in Baghdad to complete meeting with congressional Fitzwater said: "As these things "preparations for urban war leaders on the gulf crisis. -

The Transformation of Noncitizen Detention in the United States And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ASU Digital Repository From Exclusion to State Violence: The Transformation of Noncitizen Detention in the United States and Its Implications in Arizona, 1891-present by Judith Irangika Dingatantrige Perera A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved March 2018 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Jack Schermerhorn, Chair Leah Sarat Julian Lim ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzes the transformation of noncitizen detention policy in the United States over the twentieth century. For much of that time, official policy remained disconnected from the reality of experiences for those subjected to the detention regime. However, once detention policy changed into its current form, disparities between policy and reality virtually disappeared. This work argues that since its inception in the late nineteenth century to its present manifestations, noncitizen detention policy transformed from a form of exclusion to a method of state-sponsored violence. A new periodization based on detention policy refocuses immigration enforcement into three eras: exclusion, humane, and violent. When official policy became state violence, the regime synchronized with noncitizen experiences in detention marked by pain, suffering, isolation, hopelessness, and death. This violent policy followed the era of humane detentions. From 1954 to 1981, during a time of supposedly benevolent national policies premised on a narrative against de facto detentions, Arizona, and the broader Southwest, continued to detain noncitizens while collecting revenue for housing such federal prisoners. Over time increasing detentions contributed to overcrowding. -

Using a Theory of Planned Behavior Approach to Assess

USING A THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOR APPROACH TO ASSESS PRINCIPALS’ PROFESSIONAL INTENTIONS TO PROMOTE DIVERSITY AWARENESS BEYOND THE LEVEL RECOMMENDED BY THEIR DISTRICT A Dissertation by EDITH SUZANNE LANDECK Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2006 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction USING A THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOR APPROACH TO ASSESS PRINCIPALS’ PROFESSIONAL INTENTIONS TO PROMOTE DIVERSITY AWARENESS BEYOND THE LEVEL RECOMMENDED BY THEIR DISTRICT A Dissertation by EDITH SUZANNE LANDECK Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Patricia J. Larke Committee Members, Linda Skrla G. Patrick Slattery, Jr. Juan Lira Head of Department, Dennie L. Smith December 2006 Major Subject: Curriculum and Instruction iii ABSTRACT Using a Theory of Planned Behavior Approach to Assess Principals’ Professional Intentions to Promote Diversity Awareness Beyond the Level Recommended by Their District. (December 2006) Edith Suzanne Landeck, B.B.A., St. Mary’s University of San Antonio, Texas; M.B.A.-I.T., Laredo State University; M.S.E., Texas A&M International University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Patricia J. Larke The increasing population diversity in the United States and in public schools signifies a need for principals to promote diversity awareness as mandated by principal standards. A means to quantify and measure the principals’ diversity intentions empirically is required. This study researched the possibility that the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991) could provide a theoretical basis for an operation measurement model. -

ED359289.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 359 289 UD 029 316 TITLE Changing Perspectives on Civil Rights. United States Commission on Civil Rights Forum (Nashville, Tennessee, December 8-9, 1988). INSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 90 NOTE 207p.; For the proceedings of the September 1988 forum, see UD 026 315. AVAILABLE FROMU.S. Government Printing Office, Superintendent of Documents, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Asian Americans; Blacks; *Civil Rights; Demography; Dropout Rate; Economically Disadvantaged; *Economic Development; Elementary Secondary Education; *Equal Education; *Equal Opportunities (Jobs); Higher Education; Hispanic Americans; *Minority Groups; Racial Relations; *Role of Education; Social Change IDENTIFIERS Demographic Projections; Diversity (Student); Testimony ABSTRACT A subcommittee of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission heard testimony on social changes in progress and the future of civil rights, in the second in a series of forums. Thepurpose of the forum was to gather information about equal opportunities for minorities in education and economic development. Representatives from the Federal Government, public schools, the media, corporations, researchgroups, and non-profit organizations participated. Many participants pointed to the critical role education will play in preparing the next generation of Americans, especially the poor who are disproportionately minorities, to take full advantage of the opportunities in a changing society. Some participants indicated that an emphasis on education will be particularly important in view of the high dropout rates and the declining college participationrates of Blacks and Hispanics. Participants also discussed changes that have occurred in race relations over the past two decades, the importance of economic development for creating opportunities for minorities, and corporate and non-profit initiatives thatmay help to create opportunities for minorities. -

8 Grade Social Studies New South to World War I Unit Information

8th Grade Social Studies New South to World War I Unit Information Milestones Domain/Weight: History 47% Purpose/Goal: After the Civil War and Reconstruction period, Atlanta began its “rise from the ashes” and slowly became one of the more important cities in the South, proving it by hosting events such as the International Cotton Exposition. Henry Grady began to champion the cause of the “New South,” one that was industrial and self-sufficient. Entrepreneurs, both black and white, developed new services and products. One example was Alonzo Herndon, who rose from slavery to eventually own the most profitable African-American business in the country. It was also a time of terrible racism and injustice. Segregation and “Jim Crow” were the law of the land. The KKK reorganized after the murder of Mary Phagan, and this time targeted not only blacks, but Jews, Catholics, and immigrants as well. Tom Watson gained greater notoriety after he changed his position and became an ardent segregationist and anti-Semite. Additionally, Atlanta the “city too busy to hate” experienced the worst race riot in its history. During this period of racial strife, several successful African-American men became well known throughout the country for their work with civil rights. This group of men included educators W.E.B. Dubois, Booker T. Washington, along with Georgian John Hope. In addition, women, such as Rebecca Felton and Lugenia Burns Hope, made important contributions to the state. Content Map: New South to World War I Content Map New South Study/Resource