Performance Practice Issues in Russian Piano Music G. M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Piano Music Series, Vol. 13: Sergei Rachmaninov

Russian Piano Music Series, vol. 13: Sergei Rachmaninov Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) 1 Etude-Tableau in A minor, Op. 39 No. 2 8:15 Moments Musicaux, Op. 16 31:21 2 No. 1 Andantino in B flat minor 8:50 3 No. 2 Allegretto in E flat minor 3:49 4 No. 3 Andante cantabile in B minor 4:42 5 No. 4 Presto in E minor 3:32 6 No. 5 Adagio sostenuto in D flat major 4:29 7 No. 6 Maestoso in C major 5:52 Piano Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 28 40:20 8 I Allegro moderato 15:38 9 II Lento 9:34 10 III Allegro molto 15:06 total duration : 79:56 Alfonso Soldano piano Dedication I wish to dedicate this album to the great Italian pianist and professor Paola Bruni. Paola was a special friend, and there was no justice in her sad destiny; she was a superlative human being, deep, special and joyful always, as was her playing… everybody will miss you forever Paola! Alfonso Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) “The Wanderer’s Illusions” by Rosellina de Bellis ".. What I try to do, when I write my music, is to say simply and directly what is in my heart when I compose. If there is love, or bitterness, or sadness, or religion, these moods become part of my music .. " The bitterness of the words spoken by Schubert about the connection between song and love, "... when I wanted to sing love it turned into pain, and if I wanted to sing pain, it became love; so both divide my soul.. -

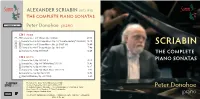

Scriabin (1872-1915) the Complete Piano Sonatas

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872-1915) THE COMPLETE PIANO SONATAS SOMMCD 262-2 Peter Donohoe piano CD 1 [74:34] 1 – 4 Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) 23:58 5 – 6 Sonata No. 2 in G Sharp Minor, Op. 19, “Sonata-Fantasy” (1892-97) 12:10 7 – bl Sonata No. 3 in F Sharp Minor, Op. 23 (1897-98) 18:40 SCRIABIN bm – bn Sonata No. 4 in F Sharp Major, Op. 30 (1903) 7:40 bo Sonata No. 5, Op. 53 (1907) 12:05 THE COMPLETE CD 2 [65:51] 1 Sonata No. 6, Op. 62 (1911) 13:13 PIANO SONATAS 2 Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” (1911) 11:47 3 Sonata No. 8, Op. 66 (1912-13) 13:27 4 Sonata No. 9, Op. 68, “Black Mass” (1912-13) 7:52 5 Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 (1913) 12:59 6 Vers La Flamme, Op. 72 (1914) 6:29 TURNER Recorded live at the Turner Sims Concert Hall SIMS Southampton on 26-28 September 2014 and 2-4 May 2015 Recording Producer: Siva Oke ∙ Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Peter Donohoe Front Cover: Peter Donohoe © Chris Cristodoulou Design & Layout: Andrew Giles piano DDD © & 2016 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND Made in the EU SCRIABIN PIANO SONATAS DISC 1 [74:34] SONATA NO. 5, Op. 53 (1907) bo Allegro. Impetuoso. Con stravaganza – Languido – 12:05 SONATA NO. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) [23:58] Presto con allegrezza 1 I. Allegro Con Fuoco 9:13 2 II. Crotchet=40 (Lento) 5:01 3 III. -

4941635-56D6e1-053479218827.Pdf

SEASCAPES The piano’s seven-plus octaves provide an ideal vessel for oceanic music, and many 1. Smetana Am Seegestade 4:58 composers have risen to the occasion. I hope that this collection serves as gateway to a 2. Bortkiewicz Caprices de la mer 3:11 treasury of pieces inspired by the limitless moods and splendor of the sea. 3-5. Guillaume At the Sea: Shining Morning 2:36 Bedřich Smetana (1824–1884), now recognized as a seminal proponent of The Rocky Beach 2:29 “Czech” music, struggled for years to establish himself as a composer and pianist. Rough Sea 3:44 Disillusioned with Prague, reeling from the death of a third young daughter, he 6. Rowley Moonlight at Sea 3:19 accepted a conducting position in the coastal town of Gothenburg, Sweden in 1856. 7. Sauer Flammes de mer 3:19 Smetana remained there in isolation for almost a year, with warm encouragement from 8. Blumenfeld Sur mer 4:37 Franz Liszt sustaining him through that desolate time. 9. Castelnuovo-Tedesco Alghe 3:37 Composed in 1861, the concert etude Am Seegestade (On the Seashore) recalls 10-12. Bloch Poems of the Sea: Waves 4:15 Smetana’s dark winter in Sweden. Tumultuous, jagged arpeggios sweep over the Chanty 2:44 keyboard before ebbing to a calm close. At Sea 4:11 13-15. Manziarly Impressions de mer: La grève 3:21 Born to a noble Polish family in Ukraine, Sergei Bortkiewicz (1877–1952) escaped Par une journée grise 2:34 to Constantinople alive but penniless following the Russian revolution. -

View Russian Chamber Music Competition Schedule 2018

! Thank you for your participation! Please take a moment to read rules and etiquette guidelines on the next page. The 2018 competition will be held all day at: Mercer Island Presbyterian Church 3605 84th Ave. SE Mercer Island, WA 98040 on December 1st, 2018. Please PRINT this attachment and bring with you to see, hear and enjoy the miraculous playing of our wonderful young musicians. We look forward to seeing you! Please check in at the registration desk where you will receive a Certificate of Achievement. ! Welcome students, parents, teachers and Russian music lovers to the 2018 Russian Chamber Music Foundation of Seattle competition & festival! In this packet, you will see the room assignments, times and the name of the adjudicator. Some very important rules apply. Please be prepared prior to the competition so that your experience will be orderly, pleasant and efficient. ~ Dahae Cheong, competition coordinator & Dr. Natalya Ageyeva, founder & artistic director. 1. PLEASE ARRIVE 15 MINUTES TO 30 MINUTES PRIOR TO YOUR COMPETITION TIME. For example, if your time block starts at 10:30, you need to be in the building around 10 or 10:15. Rushing in from the cold is not a good idea. Please plan your trip and check the internet for any freeway or road closures. You can wait outside the doors to the judging room, but once your time block starts, you should be inside the room. There are no door monitors to find you or call you in. You may also choose to be outside if you don’t enjoy hearing others or if you need a little personal space, but please keep track of the order of the performers so that you do not miss your turn. -

The First Movements of Sergei Bortkiewicz's Two Piano Sonatas, Op. 9

THE FIRST MOVEMENTS OF SERGEI BORTKIEWICZ’S TWO PIANO SONATAS, OP. 9 AND OP. 60: A COMPARISON INCLUDING SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS AND AN EXAMINATION OF CLASSICAL AND ROMANTIC INFLUENCES Yi Jing Chen, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2021 APPROVED: Gustavo Romero, Major Professor Timothy Jackson, Co-Major Professor Elvia Puccinelli, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Jaymee Haefner, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Chen, Yi Jing. The First Movements of Sergei Bortkiewicz’s Two Piano Sonatas, Op. 9 and Op. 60: A Comparison including Schenkerian Analysis and an Examination of Classical and Romantic Influences. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2021, 79 pp., 1 figure, 47 musical examples, 1 appendix, bibliography, 57 titles. The purpose of this study is to analyze the first movements of Sergei Bortkiewicz’s two piano sonatas and compare them with works by other composers that may have served as compositional models. More specifically, the intention is to examine the role of the subdominant key in the recapitulation and trace possible inspirations and influences from the Classical and Romantic styles, including Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. The dissertation employs Schenkerian analysis to elucidate the structure of Bortkiewicz’s movements. In addition, the first movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata K. 545, Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, and the first movement of Schubert’s “Trout” Quintet in A, D. 667, are examined in order to illuminate the similarities and differences between the use of the subdominant recapitulation by these composers and Bortkiewicz. -

Stylistic and Compositional Influences in the Music of Sergei Bortkiewicz Jeremiah A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 10-2016 Echoes of the Past: Stylistic and Compositional Influences in the Music of Sergei Bortkiewicz Jeremiah A. Johnson University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Commons Johnson, Jeremiah A., "Echoes of the Past: Stylistic and Compositional Influences in the Music of Sergei Bortkiewicz" (2016). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 114. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/114 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ECHOES OF THE PAST: STYLISTIC AND COMPOSITIONAL INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF SERGEI BORTKIEWICZ by Jeremiah A. Johnson A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Mark K. Clinton Lincoln, Nebraska October, 2016 ECHOES OF THE PAST: STYLISTIC AND COMPOSITIONAL INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF SERGEI BORTKIEWICZ Jeremiah A. Johnson, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2016 Adviser: Mark K. Clinton Despite the wide array of his compositional output in the first half of the twentieth century, the late Romantic composer, Sergei Bortkiewicz (1877-1952), remains relatively unknown. -

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Six Pieces from Cinderella, Op

Russian Piano Music Series, vol. 14: Sergei Prokofiev Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Six Pieces from Cinderella, Op. 102 25:26 1 I. Waltz: Cinderella and the Prince 7:29 2 II. Cinderella’s Variation 1:36 3 III. The Quarrel 3:34 4 IV. Waltz: Cinderella goes to the Ball 3:07 5 V. Pas de Chale 4.46 6 VI. Amoroso 4:52 Piano Sonata No. 6 in A major, Op. 82 31:30 7 I. Allegro moderato 9:38 8 II. Allegretto 5:10 9 III. Tempo di valzer, lentissimo 8:38 10 IV. Vivace 8:03 11 Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor, Op. 1 8:14 Four Etudes, Op. 2 11:33 12 No. 1 in D minor Allegro 2:45 13 No. 2 in E minor Moderato 2:38 14 No. 3 in C minor Andante semplice 4:19 15 No. 4 in C minor Presto energico 1:50 16 Suggestion Diabolique, Op. 4 No. 4 2:54 total duration : 79:39 Stefania Argentieri piano Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) “The Rhythmic Charm of Prokofiev” by Attilio Cantore The revolution in Russian music took place through the so-called "Group of Five", whose popularity (in the sense of Volkstümlichkeit) was the result of a successful negotiation, a magnificent syncretism, between native components (the style of harmonization of folk songs) and Central European elements (the Liszt harmonic cycles and Beethoven elaborative processes). Mily Balakirev, Cesar Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Borodin were the brave messengers of a dazzling "opening”: ‘It was as if the sky and the earth had suddenly opened, to deliver their most intimate and jealous voice. -

Darío Llanos Javierre Piano

Darío Llanos Javierre piano presentation dossier, repertoire, press pictures mobile: +1 (214) 727‑0359 (USA) +34 605 33 51 75 (Spain) email: [email protected] website: www.dariollanos.com 1. Biography Praised for “demonstrating exactly how a real musician can possess a limitless reserve of technical strength, (…) always placed in subservience to the uncompromising musical demands of the score” (Musical Opinion) and for his “clarity and exceptional tonal control” (Musical Opinion), Darío Llanos Javierre has been hailed as having an “intellectually probing pianism of forensic intensity, but delivered without fuss or excessive gesture” ( The Liszt Society Newsletter) . He is currently based in Dallas, where he holds a teaching fellowship in the College of Music at the University of North Texas for his Graduate Artist Certificate in Music Performance with Maestro Joseph Banowetz, activity he combines with his performance career, both as a soloist and as a chamber musician, and, currently, with the preparation of the recording of the entire piano works by Spanish composer Miguel del Barco for the To ccata Classics label. In 2014 he was awarded the first prize in the International Piano Prize organised by The Liszt Society in London for his interpretation of the Troisième Année of Liszt’s Années de Pèlerinage. Since then, he is regularly invited by The Liszt Society, The Keyboard Charitable Trust and Master Musicians International to give series of recitals across England. His outstanding acquaintance of Franz Liszt’s work was acknowledged again in 2016, being a prizewinner in the Los Angeles Franz Liszt International Piano Competition. He has performed in recital and as soloist with orchestra in Europe and in the United States., and was recently invited for the XX anniversary of the passing of Spanish pianist Esteban Sánchez to perform Jose Buenagu’s RhapsodyTribute (on pianistic themes by Esteban Sánchez) , followed by Franz Liszt’s Concerto Nº2 in A major, S125, one of Sánchez’s favorites, in Badajoz (Spain) with the Orquesta de Extremadura. -

Event Results Log Out: Ellyses Kuan (Admin)

5/6/2021 Event Printout Event Results Log Out: Ellyses Kuan (Admin) 51st Annual Bay State Contest, Piano Division Date: May 12, 2019 Location: Boston Conservatory at Berklee, 8 The Fenway, Boston, MA 02215 Piano 6/7A (6 years - 7 years) Contestant #5: Sophia Popescu — 1st Place (Teacher: Tanya Schwartzman) E. Grieg Poetic Tone Picture , No 1 Romantic J. Ibert A little white donkey Contemporary Contestant #2: Ethan Wei — 2nd Place (Teacher: Estelle Lin) Ludwig van Beethoven Seven Bagatelles , op.33 No.1 in E-flat Major Classical Bohuslav Martinu Nová Loutka (Shimmy) , Puppets (Loutky) Book I H.137 no.2 Contemporary Contestant #8: Claire Huang — 3rd Place (Teacher: Tong Liu) L.V.Beethoven Sonatina , F Major Classical - First movement Allegro Dmitri Kabalevsky Clown , A Major Op. 39 no.20 Contemporary Contestant #3: Raesha Chen — Honorable Mention (Teacher: Tanya Schwartzman) P. Tchaikovsky Song of the Lark, Children's Album Romantic Y. Nakada Etude Allegro Contemporary Piano 6/7B (6 years - 7 years) 03c81a2.netsolhost.com/event_registration_printout.aspx?event_id=1228 1/24 5/6/2021 Event Printout Contestant #8: Collin Zhang — 1st Place (Teacher: Lina Yen) Diabelli Sonatina in C MVT I, Op. 151 N0.2 Classical Gillock Fountain in the Rain Contemporary Contestant #3: William Huang — 2nd Place (Teacher: Tanya Schwartzman) R. Schumann From strange lands and people., Scenes from the Childhood. Romantic J. S. Bach Short Prelude, C minor Baroque Contestant #7: Kayla Fang — 2nd Place (Teacher: Yidan Guo) L.Streabbog Little Fairy by Waltz, Op105 No. 1 Romantic Tchaikovsky Song of the Lark , Op. 39 No. 22 Romantic Contestant #4: William Zelevinsky — 3rd Place (Teacher: Tanya Schwartzman) N. -

Paladino Music – Catalogue 2017

jean françaix works for clarinet paladino music dimitri ashkenazy 2017 ada meinich bernd glemser yvonne lang cincinnati philharmonia orchestra christoph-mathias mueller harald genzmer works for mixtur trautonium. from post war sounds to early krautrock catalogue paladino music peter pichler paladino music RZ-Korr_BOOKLET_pmr0075_Antheil_32-stg.qxp_Layout 1 26.07.16 16:21 Seite 1 RZ-Korr_BOOKLET_pmr0075_Antheil_32-stg.qxp_Layout 1 26.07.16 16:21 Seite 1 george antheil bad boy of music (en/de) george antheil bad boy of music (en/de) gottlieb wallisch cghortisttloiepbh ewr arolltihsch kcahrrli smtoarpkhoevirc sroth karl markovics composers / a–b Antheil: Bad Boy of Music Bach: Goldberg Variations Works by George Antheil Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 Gottlieb Wallisch, piano | Christopher Roth, narrator english Michael Tsalka, clavichord Karl Markovics, narrator german This is the first recording of the Goldberg Variations on two clavichords Antheil’s approach to piano playing is extremely physical: He compares standing side by side. Acclaimed Early Music specialist Michael Tsalka his work with that of a boxer, describes how he cools his swollen hands regularly performs this work on a variety of keyboard instrument, but in goldfish bowls and eloquently talks about sweat running down his has chosen the clavichord for his first recording of Bach’s masterwork. body in broad and greasy streams. On this recording you can hear some of his most interesting compositions played by Viennese pianist Gottlieb ”My interpretation is a bow to the spirit of improvisation, freedom and pmr 0075 (2 CDs) Wallisch. Between the piano pieces Karl Markovics and Christopher Roth unbound imagination, which shines through the music of JS Bach and his pmr 0032 antheil: are reading excerpts from Antheil’s biography „Bad Boy of Music“. -

Sergei Bortkiewicz

Russian Piano Music Series, vol. 12: Sergei Bortkiewicz Sergei Bortkiewicz (1877-1952) Lyrica Nova, Op. 59 11:08 1 I. Con moto affettuoso 3:30 2 II. Andantino 3:11 3 III. Andantino 3:18 4 IV. Con slancio 1:07 5 Etude in D flat major, Op. 15 No. 8 5:12 6 Nocturne from Trois Morceaux, Op. 24 4:52 Esquisses de Crimée, Op. 8 16:56 7 I. Les rochers d’outche-coche 6:46 8 II. Caprices de la mer 3:46 9 III. Les promenades des d’Aloupka: Idylle orientale 3:34 10 IV. Les promenades des d’Aloupka: Chaos 2:49 Three Preludes 10:06 11 Prelude, Op. 13 No. 5 4:42 12 Prelude, Op. 40 No. 4 2:51 13 Prelude, Op. 66 No. 3 2:31 Piano Sonata No. 2 in C sharp minor, Op. 60 21:24 14 I. Allegro ma non troppo 7:29 15 II. Allegretto 5:35 16 III. Andante misericordioso 5:27 17 IV. Agitato 2:52 total duration : 69:39 Alfonso Soldano piano the composer and his music Sergei Eduardovich Bortkiewicz was born in Kharkov (Ukraine) on 28 February 1877 and spent most of his childhood on the nearby family estate of Artiomowka. Bortkiewicz received his musical training from Anatol Liadov (1855-1914) and Karel van Ark (1842-1902) at the Imperial Conservatory of Music in St Petersburg. In 1900 he left St Petersburg and travelled to Leipzig, where he became a student of Salomon Jadassohn (1831-1902), Karl Piutti (1846-1902) and Alfred Reisenauer (1863-1907), who was a pupil of Liszt. -

Washington International Piano Arts Council

…………………………..……………... A Message from the Chair Welcome to the Festival of Music 2011 & The Ninth Washington International Piano Artists Competition WIPAC continues to present Summer Festival of Music & The Washington International Piano Arts Council competition in cooperation with The George Washington University Music Department, The Arts Club of Washington, and the Embassies of Bulgaria, France, Malaysia and Poland. To make the event special, the Welcome Reception is hosted under the gracious patronage of H. E. the Ambassadors of Poland and Mrs. Robert Kupiecki, in honor of these wonderful international pianists. WIPAC and all our guests cordially welcome them as we open the festivities of the week. We are very privileged and grateful for the full participation and support of the Cultural Affairs of the Embassy of Poland and I personally extend a special note of thanks to Ambassador Kupiecki for the hospitality and generous gestures he has extended to WIPAC as our organization continues to present unique and exciting cultural events in DC, where music lives. Something new this year is an intensive seminar on piano and performance to be conducted by pianist and WIPAC juror, Professor Tzvetan Konstantinov of GWU Faculty entitled “Boot Camp for Pianists”. All are invited to attend: pianists, teachers, mere lovers of music and other mortals aspiring to learn what it takes to become a performing artist. If you have missed this whirlwind of activities called “Festival of Music”, one should not miss the Piano Marathon at The Arts Club of Washington where pianists who did not make it to the next level get another chance to show off the rest of their program in this historical venue in DC.