How Jewish Was Felix Mendelssohn?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Russian Piano Music Series, Vol. 13: Sergei Rachmaninov

Russian Piano Music Series, vol. 13: Sergei Rachmaninov Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) 1 Etude-Tableau in A minor, Op. 39 No. 2 8:15 Moments Musicaux, Op. 16 31:21 2 No. 1 Andantino in B flat minor 8:50 3 No. 2 Allegretto in E flat minor 3:49 4 No. 3 Andante cantabile in B minor 4:42 5 No. 4 Presto in E minor 3:32 6 No. 5 Adagio sostenuto in D flat major 4:29 7 No. 6 Maestoso in C major 5:52 Piano Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 28 40:20 8 I Allegro moderato 15:38 9 II Lento 9:34 10 III Allegro molto 15:06 total duration : 79:56 Alfonso Soldano piano Dedication I wish to dedicate this album to the great Italian pianist and professor Paola Bruni. Paola was a special friend, and there was no justice in her sad destiny; she was a superlative human being, deep, special and joyful always, as was her playing… everybody will miss you forever Paola! Alfonso Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) “The Wanderer’s Illusions” by Rosellina de Bellis ".. What I try to do, when I write my music, is to say simply and directly what is in my heart when I compose. If there is love, or bitterness, or sadness, or religion, these moods become part of my music .. " The bitterness of the words spoken by Schubert about the connection between song and love, "... when I wanted to sing love it turned into pain, and if I wanted to sing pain, it became love; so both divide my soul.. -

La Clemenza Di Tito

La clemenza di Tito La clemenza di Tito (English: The Clemency of Titus), K. 621, is an opera seria in La clemenza di T ito two acts composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an Italian libretto by Caterino Mazzolà, after Pietro Metastasio. It was started after the bulk of Die Zauberflöte Opera by W. A. Mozart (The Magic Flute), the last opera that Mozart worked on, was already written. The work premiered on 6 September 1791 at theEstates Theatre in Prague. Contents Background Performance history Roles Instrumentation Synopsis Act 1 The composer, drawing by Doris Act 2 Stock, 1789 Recordings Translation The Clemency of Titus See also References Librettist Caterino Mazzolà External links Language Italian Based on libretto by Pietro Metastasio Background Premiere 6 September 1791 In 1791, the last year of his life, Mozart was already well advanced in writing Die Estates Theatre, Zauberflöte by July when he was asked to compose an opera seria. The commission Prague came from the impresario Domenico Guardasoni, who lived in Prague and who had been charged by the Estates of Bohemia with providing a new work to celebrate the coronation of Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor, as King of Bohemia. The coronation had been planned by the Estates in order to ratify a political agreement between Leopold and the nobility of Bohemia (it had rescinded efforts of Leopold's brother Joseph II to initiate a program to free the serfs of Bohemia and increase the tax burden of aristocratic landholders). Leopold desired to pacify the Bohemian nobility in order to forestall revolt and strengthen his empire in the face of political challenges engendered by the French Revolution. -

Susan Rutherford: »Bel Canto« and Cultural Exchange

Susan Rutherford: »Bel canto« and cultural exchange. Italian vocal techniques in London 1790–1825 Schriftenreihe Analecta musicologica. Veröffentlichungen der Musikgeschichtlichen Abteilung des Deutschen Historischen Instituts in Rom Band 50 (2013) Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Rom Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat der Creative- Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) unterliegt. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Den Text der Lizenz erreichen Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode »Bel canto« and cultural exchange Italian vocal techniques in London 1790–1825 Susan Rutherford But let us grant for a moment, that the polite arts are as much upon the decline in Italy as they are getting forward in England; still you cannot deny, gentlemen, that you have not yet a school which you can yet properly call your own. You must still admit, that you are obliged to go to Italy to be taught, as it has been the case with your present best artists. You must still submit yourselves to the direction of Italian masters, whether excellent or middling. Giuseppe -

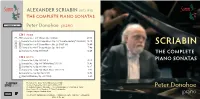

Scriabin (1872-1915) the Complete Piano Sonatas

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872-1915) THE COMPLETE PIANO SONATAS SOMMCD 262-2 Peter Donohoe piano CD 1 [74:34] 1 – 4 Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) 23:58 5 – 6 Sonata No. 2 in G Sharp Minor, Op. 19, “Sonata-Fantasy” (1892-97) 12:10 7 – bl Sonata No. 3 in F Sharp Minor, Op. 23 (1897-98) 18:40 SCRIABIN bm – bn Sonata No. 4 in F Sharp Major, Op. 30 (1903) 7:40 bo Sonata No. 5, Op. 53 (1907) 12:05 THE COMPLETE CD 2 [65:51] 1 Sonata No. 6, Op. 62 (1911) 13:13 PIANO SONATAS 2 Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” (1911) 11:47 3 Sonata No. 8, Op. 66 (1912-13) 13:27 4 Sonata No. 9, Op. 68, “Black Mass” (1912-13) 7:52 5 Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 (1913) 12:59 6 Vers La Flamme, Op. 72 (1914) 6:29 TURNER Recorded live at the Turner Sims Concert Hall SIMS Southampton on 26-28 September 2014 and 2-4 May 2015 Recording Producer: Siva Oke ∙ Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Peter Donohoe Front Cover: Peter Donohoe © Chris Cristodoulou Design & Layout: Andrew Giles piano DDD © & 2016 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND Made in the EU SCRIABIN PIANO SONATAS DISC 1 [74:34] SONATA NO. 5, Op. 53 (1907) bo Allegro. Impetuoso. Con stravaganza – Languido – 12:05 SONATA NO. 1 in F Minor, Op. 6 (1892) [23:58] Presto con allegrezza 1 I. Allegro Con Fuoco 9:13 2 II. Crotchet=40 (Lento) 5:01 3 III. -

4941635-56D6e1-053479218827.Pdf

SEASCAPES The piano’s seven-plus octaves provide an ideal vessel for oceanic music, and many 1. Smetana Am Seegestade 4:58 composers have risen to the occasion. I hope that this collection serves as gateway to a 2. Bortkiewicz Caprices de la mer 3:11 treasury of pieces inspired by the limitless moods and splendor of the sea. 3-5. Guillaume At the Sea: Shining Morning 2:36 Bedřich Smetana (1824–1884), now recognized as a seminal proponent of The Rocky Beach 2:29 “Czech” music, struggled for years to establish himself as a composer and pianist. Rough Sea 3:44 Disillusioned with Prague, reeling from the death of a third young daughter, he 6. Rowley Moonlight at Sea 3:19 accepted a conducting position in the coastal town of Gothenburg, Sweden in 1856. 7. Sauer Flammes de mer 3:19 Smetana remained there in isolation for almost a year, with warm encouragement from 8. Blumenfeld Sur mer 4:37 Franz Liszt sustaining him through that desolate time. 9. Castelnuovo-Tedesco Alghe 3:37 Composed in 1861, the concert etude Am Seegestade (On the Seashore) recalls 10-12. Bloch Poems of the Sea: Waves 4:15 Smetana’s dark winter in Sweden. Tumultuous, jagged arpeggios sweep over the Chanty 2:44 keyboard before ebbing to a calm close. At Sea 4:11 13-15. Manziarly Impressions de mer: La grève 3:21 Born to a noble Polish family in Ukraine, Sergei Bortkiewicz (1877–1952) escaped Par une journée grise 2:34 to Constantinople alive but penniless following the Russian revolution. -

View Russian Chamber Music Competition Schedule 2018

! Thank you for your participation! Please take a moment to read rules and etiquette guidelines on the next page. The 2018 competition will be held all day at: Mercer Island Presbyterian Church 3605 84th Ave. SE Mercer Island, WA 98040 on December 1st, 2018. Please PRINT this attachment and bring with you to see, hear and enjoy the miraculous playing of our wonderful young musicians. We look forward to seeing you! Please check in at the registration desk where you will receive a Certificate of Achievement. ! Welcome students, parents, teachers and Russian music lovers to the 2018 Russian Chamber Music Foundation of Seattle competition & festival! In this packet, you will see the room assignments, times and the name of the adjudicator. Some very important rules apply. Please be prepared prior to the competition so that your experience will be orderly, pleasant and efficient. ~ Dahae Cheong, competition coordinator & Dr. Natalya Ageyeva, founder & artistic director. 1. PLEASE ARRIVE 15 MINUTES TO 30 MINUTES PRIOR TO YOUR COMPETITION TIME. For example, if your time block starts at 10:30, you need to be in the building around 10 or 10:15. Rushing in from the cold is not a good idea. Please plan your trip and check the internet for any freeway or road closures. You can wait outside the doors to the judging room, but once your time block starts, you should be inside the room. There are no door monitors to find you or call you in. You may also choose to be outside if you don’t enjoy hearing others or if you need a little personal space, but please keep track of the order of the performers so that you do not miss your turn. -

The First Movements of Sergei Bortkiewicz's Two Piano Sonatas, Op. 9

THE FIRST MOVEMENTS OF SERGEI BORTKIEWICZ’S TWO PIANO SONATAS, OP. 9 AND OP. 60: A COMPARISON INCLUDING SCHENKERIAN ANALYSIS AND AN EXAMINATION OF CLASSICAL AND ROMANTIC INFLUENCES Yi Jing Chen, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2021 APPROVED: Gustavo Romero, Major Professor Timothy Jackson, Co-Major Professor Elvia Puccinelli, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Jaymee Haefner, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Chen, Yi Jing. The First Movements of Sergei Bortkiewicz’s Two Piano Sonatas, Op. 9 and Op. 60: A Comparison including Schenkerian Analysis and an Examination of Classical and Romantic Influences. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2021, 79 pp., 1 figure, 47 musical examples, 1 appendix, bibliography, 57 titles. The purpose of this study is to analyze the first movements of Sergei Bortkiewicz’s two piano sonatas and compare them with works by other composers that may have served as compositional models. More specifically, the intention is to examine the role of the subdominant key in the recapitulation and trace possible inspirations and influences from the Classical and Romantic styles, including Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. The dissertation employs Schenkerian analysis to elucidate the structure of Bortkiewicz’s movements. In addition, the first movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata K. 545, Beethoven’s Coriolan Overture, and the first movement of Schubert’s “Trout” Quintet in A, D. 667, are examined in order to illuminate the similarities and differences between the use of the subdominant recapitulation by these composers and Bortkiewicz. -

Cremona Baroque Music 2018

Musicology and Cultural Heritage Department Pavia University Cremona Baroque Music 2018 18th Biennial International Conference on Baroque Music A Programme and Abstracts of Papers Read at the 18th Biennial International Conference on Baroque Music Crossing Borders: Music, Musicians and Instruments 1550–1750 10–15 July 2018 Palazzo Trecchi, Cremona Teatro Bibiena, Mantua B Crossing Borders: Music, Musicians and Instruments And here you all are from thirty-one countries, one of Welcome to Cremona, the city of Monteverdi, Amati and the largest crowds in the whole history of the Biennial Stradivari. Welcome with your own identity, to share your International Conference on Baroque Music! knowledge on all the aspects of Baroque music. And as we More then ever borders are the talk of the day. When we do this, let’s remember that crossing borders is the very left Canterbury in 2016, the United Kingdom had just voted essence of every cultural transformation. for Brexit. Since then Europe—including Italy— has been It has been an honour to serve as chair of this international challenged by migration, attempting to mediate between community. My warmest gratitude to all those, including humanitarian efforts and economic interests. Nationalist the Programme Committee, who have contributed time, and populist slogans reverberate across Europe, advocating money and energy to make this conference run so smoothly. barriers and separation as a possible panacea to socio- Enjoy the scholarly debate, the fantastic concerts and political issues. Nevertheless, we still want to call ourselves excursions. Enjoy the monuments, the food and wine. European, as well as Italian, German, French, Spanish, And above all, Enjoy the people! English etc. -

Performance Practice Issues in Russian Piano Music G. M

PERFORMANCE PRACTICE ISSUES IN RUSSIAN PIANO MUSIC G. M. SMITH PERFORMANCE PRACTICE ISSUES IN RUSSIAN PIANO MUSIC by GREGORY MICHAEL SMITH A.mus.A., L.mus.A., B.mus. (Hon.) Submitted for the degree of MASTER OF CREATIVE ARTS February 2003 I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis is the result of original research and has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other University or Institution. ___________________________ CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE PIANO MINIATURE 3 Scriabin: Poèmes (op.32), Scherzo (op.46), Rêverie (op.49) 3 Rachmaninoff: Six Moments Musicaux (op.16) 16 Liadoff: Preludes (op.11 no.1 & op.39 no.4) 27 Sorokin: Three Dances (op.30a), Dance (op.29 no.2) 34 Shostakovich: Preludes (op.34 nos.2, 5, 9, 10, 20) 41 CHAPTER 2: THE RUSSIAN ETUDE 47 Bortkiewicz: Le Poète (op.29 no.5) & Le Héros (op.29 no.6) 48 Rachmaninoff: Etudes Tableaux (op.33 no.3, 4 & 7, op.39 no.2) 63 Scriabin: Etudes (op.2 no.1 & op.42) 80 Prokofiev: Etudes (op.2 no.1 & 2) 101 CHAPTER 3: RUSSIAN PIANO MUSIC DISPLAYING EXTRA-MUSICAL THEMES: PROGRAMMATIC MUSIC AND THE RUSSIAN ELEGY 108 Tchaikovsky: The Seasons (op.37 bis nos 1, 2, 4, 9, 10 & 12) 108 Medtner: Tales (op.20 no.1, op.34 no.2 & 4, op.42 no.1) 136 The Russian Elegy 156 Arensky: Elegy (op.36 no.16) 157 Rachmaninoff: Elegy (op.3, no.1) 163 CHAPTER 4: THE RUSSIAN PIANO SONATA Medtner: Sonata in g minor (op.22) 168 Scriabin: Sonata no.9 (op.68) 198 Kabalevsky: Sonata no.3 (op.46) 208 Baltin: Sonatine 217 CONCLUSION 224 APPENDIXES 1. -

Magnified and Sanctified: the Music of Jewish Prayer

Magnified and Sanctified – the music of Jewish Prayer June 2015 Leeds University Full Report Magnified and Sanctified: The Music of Jewish Prayer International Conference held at Leeds University, 16-19 June 2015 A Report by Dr Malcolm Miller and Dr Benjamin Wolf Pictured: Torah Mantle, Amsterdam c 1675© Victoria and Albert Museum, London Introduction and Overview A historically significant and ground-breaking event in the field of music and musicology, held at Leeds University in June 2015, set a benchmark in the field and a stimulus for rich avenues of research. Entitled Magnified and Sanctified: The Music of Jewish Prayer, the conference was the first ever International Conference on Jewish Liturgical Music in the UK , which, during the week of 16-19 June 2015, attracted an international array of leading scholars and musicians from Europe, Australia, USA and Israel to share cutting-edge research on all aspects of synagogue music past and present. The stimulating and diverse program featured an array of keynote lectures, scholarly papers, panel discussions and musical performances, and was followed by the 10th Annual European Cantors Convention weekend. The conference, presented by the European Cantor’s Association and the music department of Leeds University, was one of the inaugural events in the three-year international project ‘Performing the Jewish Archive’ (2015-2018) which has seen several major conferences and festivals across the world. Spearheaded by Dr Stephen Muir, Senior Lecturer at Leeds and Conference Director, the project has given rise to revivals of and research into much music lost during the period of the Holocaust and Jewish migrations in the 20th century. -

JEWISH SINGING and BOXING in GEORGIAN ENGLAND Shai Burstyn

Catalog TOC <<Page>> JEWISH SINGING AND BOXING IN GEORGIAN ENGLAND Shai Burstyn By their very nature, catalogues and inventoires of manuscirpts are factual and succinct, composed of dry lists of names, titles, textual and musical incipits, folio numbers, concordances, variant spellings and other similarly "inspiring" bits of information. Bits is indeed apt, for these dry bones, usually made even direr by a complex and barely decipherable mass of unfamiliar, "unfriendly" abbreviations, are merely the stuff from which the historical and musical story may be reconstructed. Yet, as every library mole knows, next to the incompar able thrill of actually holding and studying a centuriesold original manuscript, contrary to their uninviting appearance, such inventories may in fact provide many hours of exciting intellectual stimulation, of detective work fueled by numerous guesses, many of them of the category politely called "educated," but not a few also of the "wilder" variety. What Israel Adler has provided us with in Hebrew Notated Manuscript Sources RISM (Adler 1989) is a treasure house of opportunities for a lifetimeof such excitements. With its 230 manuscripts containing 3798 items and 4251 melodic incipits there is no question that for the ifrst time ever the grounds of Jewish musical manuscript sources have been surveyed, mapped and presented with a sophistication, precision and comprehensiveness destined to open a new era in the scholarly study of the ifeld. In addition to the access now gained by the student of Jewish music to the study of individual manuscripts, a master key has been provided for launching comparative studiesof groupsof manuscripts linked by all sorts of common denominators.