Little Baddow History Centre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorial to the Fallen of Danbury, 1914 1919

MEMORIAL TO THE FALLEN OF DANBURY, 1914 1919 1 Men named on the Danbury memorial, and on the tablet within St John ’s Church, Danbury, who lost their lives in the first world war The list of names has been there in the village for all to see since the memorial was put in place in 1926. Now, research has been undertaken to see what we can learn about those men, their lives, their service and their families. The list of names may not be complete. There was no government led undertaking to commemorate the fallen, or central records used; it was up to individual parishes to decide what to do. Maybe there was a parish meeting, or a prominent local person might have set things in motion, or the Royal British Legion, and parishioners would have been asked for the names of those lost. Sometimes men were associated with more than one parish, and would have relatives putting their names forward in each of them. Occasionally people did not wish the name of their loved one to be there, to be seen each time they walked past, a constant reminder of their loss. Various websites have been consulted, namely the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, Findmypast and Forces War Records. My thanks go also to Ian Hook at The Essex Regiment Museum who helped me to track down some of the men and to Alan Ridgway who allowed me to use material from his and Joanne Phillips’ comprehensive study of the lives of the “Great War Heroes of Little Baddow and their Families”, regarding Joseph Brewer and Charles Rodney Wiggins. -

Historic Environment Characterisation Project

HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT Chelmsford Borough Historic Environment Characterisation Project abc Front Cover: Aerial View of the historic settlement of Pleshey ii Contents FIGURES...................................................................................................................................................................... X ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................................................XII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................................... XIII 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ............................................................................................................................ 2 2 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF CHELMSFORD DISTRICT .................................................................................. 4 2.1 PALAEOLITHIC THROUGH TO THE MESOLITHIC PERIOD ............................................................................... 4 2.2 NEOLITHIC................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 BRONZE AGE ............................................................................................................................................... 5 -

South Woodham Ferrers in Christ, Loving and Serving God's World 8Th

service. South Woodham Ferrers Lent course: Our Lent course begins this week. The evening sessions will start on Wednesday 11th March In Christ, loving and serving at 7:30pm in Church with the sessions repeated in God’s world daytime sessions starting on Friday 13th March at 12noon in the Meeting Room. The course will run for four weeks and each session is self-contained so you can dip in and out. The course Is based on Stephen 8th March 2020 2ndt Sunday of Lent Cotrell’s book, The things he carried – and we will look at the things that Jesus took with him to the Daphne Colderwood cross. Just come along! If you need further Daphne passed away on Saturday 29th February. We information – please contact Reverend Carol. send condolences to her family. Funeral details to follow. School Kitchen Bins We have had a request from the school asking us to Welcome to our 10.00am Service. If you have a not put any rubbish in the bins in the school kitchen but hearing aid, please select the ‘T’ switch position and to take our rubbish away when we leave. benefit from our deaf loop, which is directly linked to Easter Hamper the microphones. Please join us for tea, coffee in the We are organising an Easter Hamper and we are school hall after the service. asking for donations; there will be a list during coffee for you to sign. We are hoping to have the hamper Readings: Genesis 12: 1-4a John 3: 1-17 ready for our next coffee morning (14th March) so we Prayers: Anne West can sell raffle tickets during the morning. -

Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin, Little Baddow

PARISH CHURCH OF ST MARY THE VIRGIN, LITTLE BADDOW. WELCOME ….. to this ancient and interesting church, which has a pleasant and peaceful situation at the northern end of the parish, near the River Chelmer and at the foot of the gentle rise of Danbury Hill, upon the slope of which is situated the main residential area of the parish. People have worshipped here for at least 900 years and throughout its long history, generations of Baddow folk have altered, improved and beautified this ancient building. Today it is still in regular use for Christian worship; the purpose for which it was built. We hope that you will enjoy exploring St Mary‟s and discover its features of interest and beauty. Above all, we hope that you will feel “at home” here in our Father‟s House. No visitor can fail to appreciate the love and care given to this church by its present-day custodians, who have recently spent thousands of pounds upon the building. Please pray for the priest and people whose Spiritual Home this is, and who welcome any contributions that their visitors could spare, to help them keep their ancient church intact and beautiful for future generations to use and enjoy. * * * * * * * * * EXTERIOR The church stands attractively in a trim churchyard, from which the ground descends to the west, thus explaining the unusual arrangement of buttresses which strengthen the sturdy tower. The north-west buttress is diagonal, whereas the south-west corner has angle buttresses. This 52 ft high tower is mostly work of the 14th century and has a fine west doorway with Decorated (early 14th century) window above it. -

Danbury Guide

DANBURY COUNTRY PARK & LAKES HOW TO GET TO The country park and lakes were originally part of the estate WELCOME TO surrounding the Palace. Now owned by Essex County Council, DANBURYDANBURY they are normally open from 8am to dusk. There are two pay and display car parks entered from Woodhill Road. There is also footpath access from Well Lane and from the A414 opposite DANBURYDANBURY The Bell pub. Note that the adjoining ‘Danbury Outdoors’ is not open to the public (apart from the well-marked public A hilltop village in the heart of rural Essex footpaths). Enjoy the open parkland for a picnic, take a stroll by the lakes, or walk through the woodland in the shade of ancient oaks, hornbeams and sweet chestnuts. In spring the rhododendrons are spectacular. Fishing permits are available for the lower lake from the Park Rangers. 19 DANBURY HILL FROM THE SOUTH A detailed map can be found in the Mayes Lane car park. Explore our woodlands and commons, country park and MAIN BUS ROUTES THROUGH THE VILLAGE lakes. Enjoy the panoramic views of the surrounding area. Chelmsford to Maldon Route 31, 31X Chelmsford to South Woodham Ferrers Route 36 WHILST IN THE AREA WHY NOT VISIT..... Paper Mill Lock, Little Baddow (4km/2.5m) FEEDING THE DUCKS Boat trips, tea room, canal-side walks www.papermilllock.co.uk EVES CORNER 20 Little Baddow History Centre, Chapel Lane, Little Baddow (4km/2.5m) This is the centre of our village with picturesque shops, www.thehistorycentre.org.uk village green and duck pond. Relax on the seats, enjoy a RHS Garden, Hyde Hall (7km4.5m) cuppa at the tea shop, or have a pint in one of the nearby pubs. -

CHELMSFORD CITY LOCAL HIGHWAY PANEL POTENTIAL SCHEMES LIST (Version 35)

CHELMSFORD CITY LOCAL HIGHWAY PANEL POTENTIAL SCHEMES LIST (Version 35) This Potential Scheme List identifies all of the scheme requests which have been received for the consideration of the Chelmsford City Local Highways Panel. The Panel are asked to review the schemes on the attached Potential Scheme List, finalise their scheme funding recommendations for the schemes they wish to see delivered in 2018/19 and remove any schemes the Panel would not wish to consider for future funding. There are currently potential schemes with an estimated cost of £1,532,300 as shown in the summary below - Potential Schemes List (Version 35) Estimated Scheme Costs Ref. Scheme Type Total 2018/19 Priority schemes 1 Traffic Management £362,800 £50,000 & TBC (5 schemes) 2 Cycling £959,500 £149,500 3 School Crossing Patrol TBC TBC (1 scheme) 4 Passenger Transport £85,500 £0 5 Public Rights of Way £124,500 £46,500 Total £1,532,300 £246,000 Page 1 of 14 CHELMSFORD CITY LOCAL HIGHWAY PANEL POTENTIAL SCHEMES LIST (Version 35) On the Potential Schemes List the RAG column acknowledges the status of the scheme request as shown below: RAG Description of RAG status Status G The scheme has been validated as being feasible and is available for Panel consideration A The scheme has been commissioned for a feasibility study which needs completing before any Panel consideration R A scheme which is against policy or where there is no appropriate engineering solution V A scheme request has been received and is in the initial validation process Page 2 of 14 Traffic Management -

Education in Essex 2006/2007

Determined Admission Arrangements for Community and Voluntary Controlled Infant, Junior and Primary Schools in Essex for 2015/2016 Individual policies and over-subscription criteria are set out in this document in district order. The following information applies: Looked after Children A ‘looked after child’ or a child who was previously looked after but immediately after being looked after became subject to an adoption, residence or special guardianship order will be given first priority in oversubscription criteria ahead of all other applicants in accordance with the School Admissions Code 2012. A looked after child is a child who is (a) in the care of a local authority, or (b) being provided with accommodation by a local authority in the exercise of their social services functions (as defined in Section 22(1) of the Children Act 1989). Children with statements of special educational needs Children with statements of special educational needs that name the school on the statement are required to be admitted to a school regardless of their place in the priority order. Age of Admission Essex County Council’s policy is that children born on and between 1 September 2010 and 31 August 2011 would normally commence primary school in Reception in the academic year beginning in September 2015. As required by law, all Essex infant and primary schools provide for the full-time admission of all children offered a place in the Reception year group from the September following their fourth birthday. Therefore, if a parent wants a full-time place for their child from September (at the school at which a place has been offered) then they are entitled to that full-time place. -

A Role Description for the Newly Appointed Priest in Charge of Danbury and Little Baddow

The Diocese of Chelmsford A Role Description for the newly appointed Priest in Charge of Danbury and Little Baddow Name of appointed candidate: Role title (as on licence): Priest in Charge Proportion of time given to this role,: Full time Name of benefice: St John the Baptist Danbury and St Mary the Virgin Little Baddow Deanery: Chelmsford South Archdeaconry: Chelmsford Date you started in this role: Date of this Role Description: Winter 2017/18 During the vacancy, the team parish identified the following priorities The Key A) What is to be done? B) With whom is this to be C) To what end is it to areas of done? be done? work Develop strategies to enable both The leadership of the churches That the worshipping churches to grow numerically, and those involved in village and community grows and the including using the opportunities school life age range mirrors that of available with a church school the communities which Mission, they serve Service and Outreach Enable both churches to be a Those members of the That the churches may more visible presence in their worshipping community who are provide an effective communities and to engage with actively involved with the life of Christian presence in all the life of both villages their village; those in leadership aspects of village life roles in the villages Develop, maintain and encourage The leadership of the churches, That people in the Pastoral pastoral, bereavement and support and all those currently engaged churches and villages may Care work for the sick and needy in the with or called -

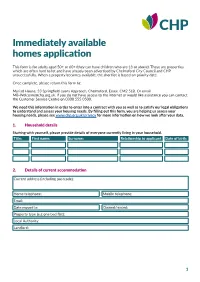

Immediately Available Homes Application

Immediately available homes application This form is for adults aged 50+ or 60+ (they can have children who are 18 or above). These are properties which are often hard to let and have already been advertised by Chelmsford City Council and CHP unsuccessfully. When a property becomes available, the shortlist is based on priority date. Once complete, please return this form to: Myriad House, 33 Springfield Lyons Approach, Chelmsford, Essex. CM2 5LB. Or email [email protected]. If you do not have access to the internet or would like assistance you can contact the Customer Service Centre on 0300 555 0500. We need this information in order to enter into a contract with you as well as to satisfy our legal obligations to understand and assess your housing needs. By filling out this form, you are helping us assess your housing needs, please see www.chp.org.uk/privacy for more information on how we look after your data. 1. Household details Starting with yourself, please provide details of everyone currently living in your household. Title: First name: Surname: Relationship to applicant Date of birth: 2. Details of current accommodation Current address (including postcode): Home telephone: Mobile telephone: Email: Date moved in: Owned/rented: Property type (e.g one bed flat): Local Authority: Landlord: 1 If you have lived at your current address for less than five years, please give your previous addresses for the last five years: Address (include postcode): Date moved Date moved Landlord: Reason for leaving: in: out: Do you currently own, any other property here or abroad? Yes No If yes, please state address: Is this property subject to be sold Yes No What is the main reason for wanting to move from your last settled home? Do you have any pets that you would want to live with you? Yes No If yes, please provide details: 3. -

Local Wildlife Site Review 2016 Appendix 1

APPENDIX 1 SUMMARY TABLE OF 2016 LOCAL WILDLIFE SITES Sites retain their original numbers, as identified in 2004, so any gaps within numbers 1-150 are where Sites have been dropped from the LoWS register. Sites 151-186 are new LoWS. Site Reference No. and Name Area (hectares) Grid Reference Ch1 Horsfrithpark Wood, Radley Green 6.22 TL 61610434 Ch2 Bushey-hays Spring, Roxwell 0.49 TL 61710847 Ch3 River Can Floodplain, Good Easter 7.85 TL 61811208 Ch4 Skreens Wood, Roxwell 3.3 TL 62060920 Ch5 Sandpit Wood, Roxwell 2.32 TL 62180745 Ch6 Parson’s Spring, Loves Green 27.48 TL 62290271 Ch7 Barrow Wood/Birch Spring, Loves Green 78.64 TL 62820236 Ch9 Engine Spring/Ring Grove, Roxwell 2.25 TL 63320768 Ch10 Hopgarden Spring, Roxwell 1.44 TL 63520787 Ch11 Cooley Spring, Roxwell 1.79 TL 63630903 Ch12 Chalybeate Spring Meadows, Good Easter 2.84 TL 63611159 Ch13 Road Verge 9, Roxwell 0.05 TL 63650997 Ch14 Writtle High Woods, Loves Green 49.64 TL 64010257 Ch16 Boyton Cross Verges, Roxwell 0.75 TL 64440973 Ch17 Nightingale Wood, Mashbury 4.86 TL 65211065 Ch18 Lady Grove, Writtle 5.19 TL 65530540 Ch19 Writtlepark Woods, Margaretting 48.91 TL 65650294 Ch20 Bushey Wood, Margaretting 3.04 TL 65700146 Ch21 James’s Spring, Margaretting 2.3 TL 65840242 Ch22 Great/Little Edney Woods, Edney Common 25.36 TL 65810385 Ch23 Lee Wood, Writtle 3.24 TL 65870474 Ch24 Osbourne’s Wood, Margaretting 1.89 TL 66000112 Ch26 Cow Watering Lane Verge, Writtle 0.05 TL 66540703 Ch28 Pleshey Castle, Pleshey 3.15 TL 66531441 Ch29 Rook Wood, Margaretting 4.19 TQ 66749985 Ch30 King -

Chelmsford City Council Review of Polling Districts and Polling Places 2014

APPENDIX 1 CHELMSFORD CITY COUNCIL REVIEW OF POLLING DISTRICTS AND POLLING PLACES 2014 Introduction The aim of the review is to ensure that polling districts are logical and reflect the local community and that polling places are conveniently located and accessible. This review is an opportunity for electors and any other interested parties within Chelmsford to express their views on the existing polling district boundaries and polling places. A polling district is a geographical sub-division of an electoral area. All wards within Chelmsford are divided into polling districts, which form the basis upon which the register of electors is produced. Most are defined by parish boundaries, geographical or man-made features, but there are exceptions. A polling place is the geographical area within which a polling station is located. In the absence of any legal definition, this can be regarded as widely as the entire polling district or as narrowly as the actual building used as a polling station. Summary of Proposals Other than those referred to below, no changes are proposed to existing polling districts and polling places. The exceptions are: Proposal Polling district Proposal Polling district Proposal Polling district No. No. No. 11 Dorset Avenue 20 Central 63 Broomfield North 14 Civic 28 Melbourne 67 Little Waltham 15 Rectory Lane 34 Holy Trinity 68 Chignal 19 Victoria Road 57 Collingwood 74 Writtle South 1 PROPOSALS Proposal Polling District Proposal for District Reason for District Proposal Map No. No. Parliamentary Electorate (Aug 2014) Proposal for Polling Place Reason for Polling Place Proposal Existing Polling Place Chelmsford Constituency / Chelmer Village and Beaulieu Park Ward 1. -

Essex County Council Primary School Admissions Brochure for Mid Essex

Schools Admission Policies Directory 2021/2022 Mid Essex Braintree, Chelmsford and Maldon Districts Apply online at www.essex.gov.uk/admissions Page 2 Mid Essex Online admissions Parents and carers who live in the Essex You will be able to make your application County Council area (excluding those online from 9 November 2020. living in the Borough of Southend-on-Sea or in Thurrock) can apply for their child’s The closing date for primary applications is 15 January 2021. This is the statutory national school place online using the Essex closing date set by the Government. Online Admissions Service at: www.essex.gov.uk/admissions The online application system has a number of benefits for parents and carers: • you can access related information through links on the website to find out more about individual schools, such as home to school transport or inspection reports; • when you have submitted your application you will receive an email confirming this; • you will be told the outcome of your online application by email on offer day if you requested this when you applied. Key Points to Remember • APPLY ON TIME - closing date 15 January 2021. • Use all 4 preferences. • Tell us immediately in writing (email or by letter) about any address change. • Make sure you read and understand the Education Transport Policy information on www. essex.gov.uk/schooltransport if entitlement to school transport is important to you. School priority admission (catchment) areas are not relevant to transport eligibility. Transport is generally only provided to the nearest available school where the distance criteria is met.