Talmudic Literature As a Historical Source

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

Chapter Fourteen Rabbinic and Other Judaisms, from 70 to Ca

Chapter Fourteen Rabbinic and Other Judaisms, from 70 to ca. 250 The war of 66-70 was as much a turning point for Judaism as it was for Christianity. In the aftermath of the war and the destruction of the Jerusalem temple Judaeans went in several religious directions. In the long run, the most significant by far was the movement toward rabbinic Judaism, on which the source-material is vast but narrow and of dubious reliability. Other than the Mishnah, Tosefta and three midrashim, almost all rabbinic sources were written no earlier than the fifth century (and many of them much later), long after the events discussed in this chapter. Our information on non-rabbinic Judaism in the centuries immediately following the destruction of the temple is scanty: here we must depend especially on archaeology, because textual traditions are almost totally lacking. This is especially regrettable when we recognize that two non-rabbinic traditions of Judaism were very widespread at the time. Through at least the fourth century the Hellenistic Diaspora and the non-rabbinic Aramaic Diaspora each seem to have included several million Judaeans. Also of interest, although they were a tiny community, are Jewish Gnostics of the late first and second centuries. The end of the Jerusalem temple meant also the end of the Sadducees, for whom the worship of Adonai had been limited to sacrifices at the temple. The great crowds of pilgrims who traditionally came to the city for the feasts of Passover, Weeks and Tabernacles were no longer to be seen, and the temple tax from the Diaspora that had previously poured into Jerusalem was now diverted to the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus in Rome. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Hanne Trautner-Kromann n this introduction I want to give the necessary background information for understanding the nine articles in this volume. II start with some comments on the Hebrew or Jewish Bible and the literature of the rabbis, based on the Bible, and then present the articles and the background information for these articles. In Jewish tradition the Bible consists of three main parts: 1. Torah – Teaching: The Five Books of Moses: Genesis (Bereshit in Hebrew), Exodus (Shemot), Leviticus (Vajikra), Numbers (Bemidbar), Deuteronomy (Devarim); 2. Nevi’im – Prophets: (The Former Prophets:) Joshua, Judges, Samuel I–II, Kings I–II; (The Latter Prophets:) Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezek- iel; (The Twelve Small Prophets:) Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephania, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi; 3. Khetuvim – Writings: Psalms, Proverbs, Job, The Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, Chronicles I–II1. The Hebrew Bible is often called Tanakh after these three main parts: Torah, Nevi’im and Khetuvim. The Hebrew Bible has been interpreted and reinterpreted by rab- bis and scholars up through the ages – and still is2. Already in the Bible itself there are examples of interpretation (midrash). The books of Chronicles, for example, can be seen as a kind of midrash on the 10 | From Bible to Midrash books of Samuel and Kings, repeating but also changing many tradi- tions found in these books. In talmudic times,3 dating from the 1st to the 6th century C.E.(Common Era), the rabbis developed and refined the systems of interpretation which can be found in their literature, often referred to as The Writings of the Sages. -

Israeli History

1 Ron’s Web Site • North Shore Flashpoints • http://northshoreflashpoints.blogspot.com/ 2 • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wb6IiSUx pgw 3 British Mandate 1920 4 British Mandate Adjustment Transjordan Seperation-1923 5 Peel Commission Map 1937 6 British Mandate 1920 7 British Mandate Adjustment Transjordan Seperation-1923 8 9 10 • Israel after 1973 (Yom Kippur War) 11 Israel 1982 12 2005 Gaza 2005 West Bank 13 Questions & Issues • What is Zionism? • History of Zionism. • Zionism today • Different Types of Zionism • Pros & Cons of Zionism • Should Israel have been set up as a Jewish State or a Secular State • Would Israel have been created if no Holocaust? 14 Definition • Jewish Nationalism • Land of Israel • Jewish Identity • Opposes Assimilation • Majority in Jewish Nation Israel • Liberation from antisemetic discrimination and persecution that has occurred in diaspora 15 History • 16th Century, Joseph Nasi Portuguese Jews to Tiberias • 17th Century Sabbati Zebi – Declared himself Messiah – Gaza Settlement – Converted to Islam • 1860 Sir Moses Montefiore • 1882-First Aliyah, BILU Group – From Russia – Due to pogroms 16 Initial Reform Jewish Rejection • 1845- Germany-deleted all prayers for a return to Zion • 1869- Philadelphia • 1885- Pittsburgh "we consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religious community; and we therefore expect neither a return to Palestine, nor a sacrificial worship under the sons of Aaron, nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning a Jewish state". 17 Theodore Herzl 18 Theodore Herzl 1860-1904 • Born in Pest, Hungary • Atheist, contempt for Judaism • Family moves to Vienna,1878 • Law student then Journalist • Paris correspondent for Neue Freie Presse 19 "The Traitor" Degradation of Alfred Dreyfus, 5th January 1895. -

The Nasi, the Judge and the Hostages: Loans and Oaths in Thirteenth-Century Narbonne

The Nasi, the Judge and the Hostages: Loans and Oaths in Thirteenth-Century Narbonne Pinchas Roth1 The Nesi’im, or Jewish “princes,” in Narbonne have aroused the curiosity and imaginations of people – Jewish and Christian alike – for centuries.2 As described by their earliest chronicler, the so-called Proven�al addition to Sefer ha-Kabbalah (The Book of Tradition), the Nesi’im were characterized by a combination of worldly wealth, political clout and rabbinic expertise.3 Their wealth and political status faded during the thirteenth century, but their status as respected aristocrats endured until the expulsion of the Jewish community in 1306.4 1 I would like to thank the members of the “Rethinking Early Modern Jewish Legal Culture: New Sources, Methodologies and Paradigms” research group at the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies, 2018–2019 for their feedback, Claire Soussen and Sarah Maugin for their constructive comments, and Menachem Butler for his invaluable help. This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 281/18). 2 E.M. Rose, The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 86; Arthur J. Zuckerman, A Jewish Princedom in Feudal France, 768–900 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1972); Jonathan Levi, Septimania: A Novel (New York: Overlook Press, 2016). For a resounding rebuttal of Zuckerman’s theory, see Jeremy Cohen, “The Nasi of Narbonne: A Problem in Medieval Historiography,” AJSR 2 (1977): 45–76. 3 “We have a tradition that in Narbonne they have a chain of grandeur in Torah and Nesi’ut and Ge’onut.” Ms New York, Jewish Theological Seminary, Rab. -

Yom Kippur 2015 Rabbi Carl M. Perkins Temple Aliyah Needham, MA

“Let’s Have a Conversation…” Yom Kippur 2015 Rabbi Carl M. Perkins Temple Aliyah Needham, MA I want to tell you a story about a famous rabbi, Rabbi Yehudah Ha-Nasi. Rabbi Yehudah lived in the Land of Israel at the end of the second century. He was an influential Jewish leader. He was selected to be the Nasi, the Patriarch, with apparently many administrative, legislative and judicial responsibilities. He edited the Mishnah, a comprehensive Jewish legal code. He was also beloved and looked up to by his fellow rabbis and scholars. This is the story about the day he died. The Talmud tells it this way:1 Rabbi Yehudah ha-Nasi was very, very ill. It was clear to him and to those around him that he was dying. He called for his sons, and when they arrived, he gave them instructions. Take care, he said, that you show respect to your mother. Keep the home fires burning. Let my two attendants, Yosef of Haifa and Shim’on of Efrat, who attended on me during my lifetime, attend to me after my death. He called on the Sages of Israel to come forward and he ordered them: Don’t mourn for me in the small villages. I don’t want to put people out. You may mourn for me in the towns, but for no longer than thirty days. His disciples gathered in the courtyard just outside his home to pray for his recovery. Now, Rabbi Yehuda had a dear, devoted aide, a woman of great sensitivity and compassion. -

THE HANDBOOK of PALESTINE MACMILLAN and CO., Limited

VxV'*’ , OCT 16 1923 i \ A / <$06JCAL Division DSI07 S; ct Ion .3.LB Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Princeton Theological Seminary Library https://archive.org/details/handbookofpalestOOIuke THE HANDBOOK OF PALESTINE MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA • MADRAS MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO DALLAS • SAN FRANCISCO THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd TORONTO DOME OF THE ROCK AND DOME OF THE CHAIN, JERUSALEM. From a Drawing by Benton Fletcher. THE HANDBOOK OF P A L E ST IN #F p“% / OCT 16 1923 V\ \ A A EDITED' BY V HARRY CHARLES LUKE, B.Litt., M.A. ASSISTANT GOVERNOR OF JERUSALEM AND ^ EDWARD KEITH-ROACH ASSISTANT CHIEF SECRETARY TO THE GOVERNMENT OF PALESTINE WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY The Right Hon. SIR HERBERT SAMUEL, P.C., G.B.E. HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR PALESTINE Issued under the Authority of the Government of Palestine MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON 1922 COPYRIGHT PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN PREFACE The Handbook of Palestine has been written and printed during a period of transition in the administration of the country. While the book was in the press the Council of the League of Nations formally approved the conferment on Great Britain of the Mandate for Palestine; and, consequent upon this act, a new constitution is to come into force, the nominated Advisory Council will be succeeded by a partly elected Legislative Council, and other changes in the direction of greater self-government, which had awaited the ratification of the Mandate, are becoming operative. Again, on the ist July, 1922, the adminis¬ trative divisions of the country were reorganized. -

Judah Ha-Nasi Judaism

JUDAH HA-NASI JUDAH HA-NASI al. Since the publication of his Mishnah at the end of the second or beginning of the third century, the primary pur- Head of Palestinian Jewry and codifier of the MISH- suit of Jewish sages has been commenting on its contents. NAH; b. probably in Galilee, c. 135; d. Galilee, c. 220. Judah was the son of Simeon II ben Gamaliel II, who was See Also: TALMUD. the grandson of GAMALIEL (mentioned in Acts 5.34; Bibliography: W. BACHER, The Jewish Encyclopedia. ed. J. 22.3), who was in turn the grandson of Hillel. As the pa- SINGER (New York 1901–06) 7:333–33. D. J. BORNSTEIN, Encyclo- triarch or head of Palestinian Jewry, Judah received as a paedia Judaica: Das Judentum in Geschichte und Gegenwart. permanent epithet the title ha-Nasi (the Prince), original- (Berlin 1928–34) 8:1023–35. L. LAZARUS, Universal Jewish Ency- clopedia (New York 1939–44) 6: 229–230. K. SCHUBERT, Lexikon ly given to the president of the Great Sanhedrin in Jerusa- für Theologie und Kirche, ed. J. HOFER and K. RAHNER (Freiberg lem. In the Mishnah he is referred to simply as Rabbi (the 1957–65) 5:889. A. GUTTMANN, ‘‘The Patriarch Judah I: His Birth teacher par excellence), and in the GEMARAH he is often and Death,’’ Hebrew Union College Annual 25 (1954) 239–261. called Rabbenu (our teacher) or Rabbenu ha-kadosh (our [M. J. STIASSNY] saintly teacher). He was instructed in the HALAKAH of the Oral Law by the most famous rabbis of his time, but he summed up his experience as a student, and later as a teacher, in the words: ‘‘Much of the Law have I learned JUDAISM from my teachers, more from my colleagues, but most of The term Judaism admits of various meanings. -

Jews in the Diaspora: the Bar Kohkva Revolt Submitted By

Jews In The Diaspora: The Bar Kohkva Revolt Submitted by: Jennifer Troy Subject Area: Jews in the Diaspora: Bar Kokhva Revolt Target Age group: Children (ages 9-13) –To use for adults, simply alter the questions to consider. Abstract: The lesson starts out in a cave-like area to emulate the caves used during the revolt. Then explain the history with Hadrian and how he changed his mind after a while. This lesson is to teach the children about the revolt and how they did it. They spent their time digging out caves all over the land of Israel and designing an intricate system so that they were able to get food and water in, as well as get in an out if entrances were sealed off. The students will learn about how the Romans were trying to convert the Jews--thus learning what Hellenists were. This lesson is designed to be a somewhat interactive history lesson, so that they remember it and enjoy it. The objective of this lesson is for the kids to understand what the rebellion was about, why it happened, how it happened and what it felt like to be in their situation. This is also one of the important events recognized by Tisha B'Av and it is important for the children to know it. Materials: -An outdoors setting where you can find a cave-like atmosphere -If find a cave, make sure to bring candles and matches for light in the cave. -Poster board with keywords relating to the era and revolt- if you like to teach with visuals. -

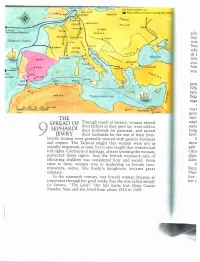

Dona Gracia Mendes Nasi and She Lived from About 1510 to 1569

Norin sen DHL SEU Route tased from 1492 HOLLAND London Route used by starranos 16 th and 1701 Centue Amsterdam PRUSSIA Aitwerp Warsaw GERMANY Cologne POLAND Mainzol Prague to Brazil, Paris be later w New Netherland BOHEMIA DNIEPER R . edic FRANCE Basel l'izuna Inqı Atlantic Ocean was RHONER Venice Bordeaux Milano Nas whe G211000 DANUBE R Ancona de L Leghorts Black Sea Marseilles Floravice tim SPAIN TURKIsu Adrianople Roma Adriatic Aarti cisc Sea • Toledo S Constantinople Nin Lisbon Naples Salonica you o the Seville ( ew World Gmiaka EMPIRE Palermo Cadiz Algiers Bizer Tangier peoj PALESTINE Whe fam AFRICA Mediterranean Sea bega tuga 100 200 300 400 500 miles EGYPT outv Ascheri Alexandria Cairo gove THE into SPREAD OF Through much of history, women served nepł their fathers as they grew up, were sold to sum SEPHARD their husbands for payment, and served long JEWRY their husbands for the rest of their lives. Jewi S Jewish women were generally treated with greater kindness and respect. The Talmud taught that women were not as mon socially important asmen , but it also taught that women had safe full rights . Contracts of marriage , always favoring thewoman , Otto protected these rights . And the Jewish woman 's role of place educating children was considered holy and sacred . From allov A time to time, women rose to leadership in Jewish com munities ; some, like Rashi's daughters, became great Here scholars . Mari In the sixteenth century, one Jewish woman became so live i important through her good works that she was called simply her i La Senora, " The Lady. -

Celebration Civilization Culture Contributions Contributors

PRESENTED BY THE ASPER FOUNDATION Celebration Civilization Culture Contributions Contributors TEL AVIV, ISRAEL Celebration Civilization Culture Contributions Contributors PRESENTED BY THE ASPER FOUNDATION 2017 A Frank Gehry museum for Tel Aviv, Israel The World’s Jewish Museum is the most ambitious and far-reaching project of its kind today. To be located in Tel Aviv, it will exhibit the spectacular array of Jewish ideas, education, thought, and creativity in every conceivable field. It engages visually and intellectually—and on a grand scale—with all things Jewish over the course of humanity’s journey. Judaism is writ large in global history, and the museum aims very high in its architecture, exhibits, scope, and passion. 6 PRESENTED BY THE ASPER FOUNDATION THE VISION The World’s Jewish Museum represents a positive paradigm focused on linking past and present contributions—with an outlook to the future. Most crucially, the World’s Jewish Museum will enhance the bond between Israel and the global Jewish population through the strengthening of its collective identity. This museum will attest to the significance of outstanding Jewish attainment and intellectual output and showcase the ways in which these contributions have shaped the path of humankind. Exhibitions and programs will also document the connection between the world’s Jewish peoples and the land of Israel. Why create the World’s Jewish Museum? The remarkable contributions of the Jewish people in the modern era—far out of proportion to their small number—is a cause for celebration and a subject for exploration. Their contributions and personalities are manifest. Whether working in a laboratory or a place of business, Jewish thinkers have transformed fundamental elements of modern life for all the world’s citizens. -

Do You Know Parshat Shoftim

QUESTIONS ON PARASHAT BEHA’ALOTCHA Q-1. (a) (1) After listing, at the end of Parashat Nasso, the gifts from each that were provided by the other nesi’im for the inauguration of the Mishkan, why did Hashem now command Aharon to kindle the menorah? (2) As the Nasi of Sheivet Levi, why did Aharon not offer these inauguration gifts like the other other nesi’im offered (3 views)? (b) (1) Why does 8:2 say, “be-ha’alotcha” (when you raise up), not “be-hadliykecha” (when you kindle) the lamps (3 views)? (2) Why did the 6 outside wicks point toward the center branch (2 reasons)? (c) (1) Why was each levi required to offer a korban chatat? (2) How was it possible for all of Bnei Yisrael to “lean their hands” (ve-samchu Bnei Yisrael”) on the levi’im (2 views)? (3) What was the purpose of the firstborns’ doing semicha on the levi’im? (d) From where do we learn that for the Torah reading on Shabbat, we divide the text of the parasha into 7 aliyot? (e) (1) On what calendar date did Moshe consecrate all of the levi’im? (2) Why did all of the hair on the body of each levi have to be shaven off? (3) Why did Aharon lift each of the 22,000 levi’im and wave them up and down and back and forth? (f) (1) Since 4:3 says that the levi’im shall work in the Mishkan beginning at age 30, why does 8:24 say, “from age 25 and up”? (2) When 8:25 says that from age 50, the levi’im shall no longer work in the Mishkan, to what avoda does this apply? (Bamidbar 8:2-19,24-25) A-1.