The Centenary of Latvia's Foreign Affairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECFG-Latvia-2021R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: A Latvian musician plays a popular folk instrument - the dūdas (bagpipe), photo courtesy of Culture Grams, ProQuest). The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on the Baltic States. Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Latvia Latvian society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre-deployment training (Photo: A US jumpmaster inspects a Latvian paratrooper during International Jump Week hosted by Special Operations Command Europe). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

Akasvayu Girona

AKASVAYU GIRONA OFFICIAL CLUB NAME: CVETKOVIC BRANKO 1.98 GUARD C.B. Girona SAD Born: March 5, 1984, in Gracanica, Bosnia-Herzegovina FOUNDATION YEAR: 1962 Career Notes: grew up with Spartak Subotica (Serbia) juniors…made his debut with Spartak Subotica during the 2001-02 season…played there till the 2003-04 championship…signed for the 2004-05 season by KK Borac Cacak…signed for the 2005-06 season by FMP Zeleznik… played there also the 2006-07 championship...moved to Spain for the 2007-08 season, signed by Girona CB. Miscellaneous: won the 2006 Adriatic League with FMP Zeleznik...won the 2007 TROPHY CASE: TICKET INFORMATION: Serbian National Cup with FMP Zeleznik...member of the Serbian National Team...played at • FIBA EuroCup: 2007 RESPONSIBLE: Cristina Buxeda the 2007 European Championship. PHONE NUMBER: +34972210100 PRESIDENT: Josep Amat FAX NUMBER: +34972223033 YEAR TEAM G 2PM/A PCT. 3PM/A PCT. FTM/A PCT. REB ST ASS BS PTS AVG VICE-PRESIDENTS: Jordi Juanhuix, Robert Mora 2001/02 Spartak S 2 1/1 100,0 1/7 14,3 1/4 25,0 2 0 1 0 6 3,0 GENERAL MANAGER: Antonio Maceiras MAIN SPONSOR: Akasvayu 2002/03 Spartak S 9 5/8 62,5 2/10 20,0 3/9 33,3 8 0 4 1 19 2,1 MANAGING DIRECTOR: Antonio Maceiras THIRD SPONSOR: Patronat Costa Brava 2003/04 Spartak S 22 6/15 40,0 1/2 50,0 2/2 100 4 2 3 0 17 0,8 TEAM MANAGER: Martí Artiga TECHNICAL SPONSOR: Austral 2004/05 Borac 26 85/143 59,4 41/110 37,3 101/118 85,6 51 57 23 1 394 15,2 FINANCIAL DIRECTOR: Victor Claveria 2005/06 Zeleznik 15 29/56 51,8 13/37 35,1 61/79 77,2 38 32 7 3 158 10,5 MEDIA: 2006/07 Zeleznik -

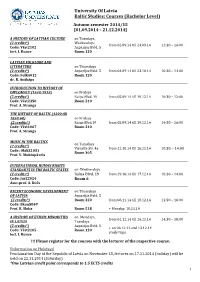

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Helsinki Watch Committees in the Soviet Republics: Implications For

FINAL REPORT T O NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTIO N AUTHORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky Tönu Parming CONTRACTOR : University of Delawar e PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky, Project Director an d Co-Principal Investigato r Tönu Parming, Co-Principal Investigato r COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 621- 9 The work leading to this report was supported in whole or in part fro m funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research . NOTICE OF INTENTION TO APPLY FOR COPYRIGH T This work has been requested for manuscrip t review for publication . It is not to be quote d without express written permission by the authors , who hereby reserve all the rights herein . Th e contractual exception to this is as follows : The [US] Government will have th e right to publish or release Fina l Reports, but only in same forma t in which such Final Reports ar e delivered to it by the Council . Th e Government will not have the righ t to authorize others to publish suc h Final Reports without the consent o f the authors, and the individua l researchers will have the right t o apply for and obtain copyright o n any work products which may b e derived from work funded by th e Council under this Contract . ii EXEC 1 Overall Executive Summary HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTION by Yaroslav Bilinsky, University of Delawar e d Tönu Parming, University of Marylan August 1, 1975, after more than two years of intensive negotiations, 35 Head s of Governments--President Ford of the United States, Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada , Secretary-General Brezhnev of the USSR, and the Chief Executives of 32 othe r European States--signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperatio n in Europe (CSCE) . -

Dear Members of the FIDE Electoral Integrity Committee, I Write Regarding the Complaint That You Have Received from Mr. Arkady

Dear members of the FIDE Electoral Integrity Committee, I write regarding the complaint that you have received from Mr. Arkady Dvorkovich, I would like to note the following; 1. The positions of principals are awarded to people on the basis of their experience and the valuable voluntary contribution towards the functioning of FIDE. This has been a standing principle. With regards to the countries mentioned in Mr. Dvorkovich's complaint; Austria, Georgia, Greece, Germany, I further inform you that; a) Nikolopoulos, Takis (GRE), Japaridze, Marika (GEO), Tandashvili, Margarita (GEO) were proposed for nomination by the Organizers b) Deventer, Klaus (GER), Kytharidis, Argiris (GRE) were proposed for nomination by Europe (ECU) c) The Chief Arbiter, Takis Nikolopoulos, proposed for nomination in order to ensure the best possible team for the pairings, the remaining three officials; Herzog, Heinz (AUT) (Owner Of Swiss Manager Program - Olympiad Version, Used In Every Olympiad Since 2010) Krause, Christian (GER) (Swiss Pairings Programs Commission Chairman, Owner Of The Swiss Pairings Program For Olympiad - Countercheck Of Swiss Manager), Stubenvoll, Werner (AUT) (Qualification Commission Chairman, Swiss Manager Program Specialist) Subsequently, out of the eight persons mentioned by Mr. Dvorkovich, neither FIDE nor I have nominated any of them. I only approved these persons, in accordance with FIDE regulations. I fear that the attack which Mr. Dvorkovich attempts to make is mainly a political one, especially in regards to Georgia, which being the country that organises the Olympiad was entitled to even more than two Principals that they were awarded to them. Regrettably, although Mr. Dvorkovich runs for the presidency of a global sports organization, he is unable to separate that from his own country's political agenda, or the clear need for a politically independent FIDE President, in accordance with the principles of the IOC to which FIDE is affiliated. -

Importance of European Remembrance for the Future of Europe

European Parliament 2019-2024 TEXTS ADOPTED P9_TA(2019)0021 Importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe European Parliament resolution of 19 September 2019 on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe (2019/2819(RSP)) The European Parliament, – having regard to the universal principles of human rights and the fundamental principles of the European Union as a community based on common values, – having regard to the statement issued on 22 August 2019 by First Vice-President Timmermans and Commissioner Jourová ahead of the Europe-Wide Day of Remembrance for the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, – having regard to the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted on 10 December 1948, – having regard to its resolution of 12 May 2005 on the 60th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe on 8 May 19451, – having regard to Resolution 1481 of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe of 26 January 2006 on the need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian Communist regimes, – having regard to Council Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA of 28 November 2008 on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law2, – having regard to the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism adopted on 3 June 2008, – having regard to its declaration on the proclamation of 23 August as European Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Stalinism and Nazism adopted on 23 September 20083, 1 OJ C 92 E, 20.4.2006, p. 392. 2 OJ L 328, 6.12.2008, p. -

Latvia's 'Russian Left': Trapped Between Ethnic, Socialist, and Social-Democratic Identities

Cheskin, A., and March, L. (2016) Latvia’s ‘Russian left’: trapped between ethnic, socialist, and social-democratic identities. In: March, L. and Keith, D. (eds.) Europe's Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream? Rowman & Littlefield: London, pp. 231-252. ISBN 9781783485352. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/133777/ Deposited on: 11 January 2017 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk This is an author’s final draft. The article has been published as: Cheskin, A. & March, L. (2016) ‘Latvia’s ‘Russian left’: Trapped between ethnic, socialist, and social-democratic identities’ in, L. March & D. Keith (eds.) Europe’s radical left: From marginality to the mainstream? Rowman and Littlefield: London, pp. 231-252. Latvia’s ‘Russian left’: trapped between ethnic, socialist, and social- democratic identities Ammon Cheskin and Luke March Following the 2008 economic crisis, Latvia suffered the worst loss of output in the world, with GDP collapsing 25 percent.1 Yet Latvia’s radical left has shown no notable ideological or strategic response. Existing RLPs did not secure significant political gains from the crisis, nor have new challengers benefitted. Indeed, Latvia has been heralded as a ‘poster child’ for austerity as the right has continued to dominate government policy.2 This chapter explores this puzzle. Although the economic crisis was economically destructive, we argue that the political responses have been consistently ethnicised in Latvia. Additionally, the Latvian left has been equally challenged intellectually and strategically by the ethnically-framed Ukrainian crisis of 2014. -

Speaker of the Saeima, Two Deputy Speakers, a Secretary and a Deputy Secretary

The Presidium of the Saeima The work of the Saeima is managed by the Presidium, which is elected by the Saeima at the beginning of its term of office. The Presidium of the Saeima consists of five members of the Saeima – the Speaker of the Saeima, two Deputy Speakers, a Secretary and a Deputy Secretary. Nominations for the positions in the Saeima Presidium are submitted by Saeima members in writing, and voting on the nominees for each position is held simultaneously by secret ballot and by using ballot papers. The nominee who receives the most votes is deemed elected; however, the number of votes should not be less than the absolute majority of votes of the members present. Members of the Presidium are usually elected from the ru- ling parties represented in the Saeima; however, the Speaker In order to coordinate the activities of parliamentary of the Saeima may also be elected from the party which has groups and political blocs, as well as to settle matters not gained the largest number of seats in the Saeima. which are not covered by the Rules of Procedure, the The Presidium of the Saeima determines the internal ru- Council of Parliamentary Groups is formed. It consists les of the Saeima, gives opinions on the documents sub- of the Saeima Presidium and one Saeima member from mitted and forwards these documents as prescribed by each parliamentary group and political bloc. Decisions of the Rules of Procedure, prepares the agenda of Saeima the Council of Parliamentary Groups are only advisory. sittings, as well as confirms planned business trips. -

Vidvuds and Lāčplēsis Viņi Joprojām Atgriežas

Justyna Prusinowska They are Still Coming Back. Heroes for the Time of Crisis .. Literatūra un reliģija DOI: http://doi.org/10.22364/lursug.03 66.–84. lpp. They are Still Coming Back. Heroes for Time of Crisis: Vidvuds and Lāčplēsis Viņi joprojām atgriežas. Varoņi krīzes laikam: Vidvuds un Lāčplēsis Justyna Prusinowska Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań E-mail: [email protected] The ground-breaking or especially difficult moments in the history of Latvia have almost always found their reflection in the literature. During each of the challenging moments an ideal hero is born, a hero ready to fight for his fatherland and nation, constituting a role model to be followed. However, Latvian writers do not create new heroes, but have been summoning the same figures for over a hundred years. The paper is going to present the stands and transformations of literary heroes – Vidvuds and Lāčplēsis – at different stages of Latvian history, as they face threats against national freedom and social integrity. Keywords: Latvian literature, Latvian national hero, Latvian national identity. During Latvian National Awakening a vital role was played by the “Young Latvians” (Latvian: jaunlatvieši) and their followers, especially through articles and poetry that they published in press. Among the plethora of very diverse texts one may find those that are devoted to the Latvian past, to its ancient religion, gods and heroes. These heroes in particular – gifted with extraordinary power and skills – were chosen as leaders and advocates of freedom and the new, better order. Throughout the entire 19th century quite a few of them appeared in the Latvian literary space, Imanta, Lāčplēsis, Vidvuds and Kurbads being the most prominent. -

M. Korostikov / Russian State and Economy

’Ifri ’Ifri _____________________________________________________________________ Leaving to Come Back: Russian Senior Officials and the State-Owned Companies _____________________________________________________________________ Mikhail Korostikov August 2015 . Russia/NIS Center Ifri is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debates and research activities. The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ alone and do not reflect the official views of their institutions. ISBN: 978-2-36567-435-5 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2015 Ifri Ifri-Bruxelles 27, rue de la Procession Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – FRANCE 1000 – Bruxelles – BELGIQUE Tél. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tél. : +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Fax : +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email : [email protected] Email : [email protected] Website : Ifri.org Russie.Nei.Visions Russie.Nei.Visions is an online collection dedicated to Russia and the other new independent states (Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan). Written by leading experts, these policy- oriented papers deal with strategic, political and economic issues. -

160 KAZACHONAK Katsiaryna / КАЗАЧЁНОК Катарина Latvian

Альманах североевропейских и балтийских исследований / Nordic and Baltic Studies Review. 2016. Issue 1 KAZACHONAK Katsiaryna / КАЗАЧЁНОК Катарина Latvian Society of Archivists / Латвийское общество архивистов Latvia, Riga / Латвия, Рига [email protected] COOPERATION OF LATVIAN BELARUSIANS WITH THE NON-BELARUSIAN POLITICAL ORGANIZATIONS OF LATVIA IN 1928—31 СОТРУДНИЧЕСТВО БЕЛОРУСОВ ЛАТВИИ С НЕБЕЛОРУССКИМИ ЛАТВИЙСКИМИ ПОЛИТИЧЕСКИМИ ОРГАНИЗАЦИЯМИ В 1928—1931 ГГ. Аннотация: В статье рассматривается вопрос о характере отношений представителей белорусского меньшинства Латвии с политическими партиями Латвии в период предвыборных кампаний в парламент второго и третьего coзывов. Именно в это время белорусы начали интенсивно искать контакты с другими политическими организациями Латвии. Поддержка белорусами социал-демократов и коммунистов была закономерна и обуславливалась социальной структурой белорусского меньшинства Латвии. В начале 1930-х гг. белорусы сделали попытку расширить свои контакты через взаимодействие с другими гражданскими партиями Латвии, которые, хотя и были левыми, выражали некоторые идеи, ранее не характерные для белорусских политических организаций (Латгальского объединения прогрессивных крестьян, Партии крестьян-христиан). Это свидетельствует, с одной стороны, о разочаровании в белорусских национальных политических партиях, а с другой стороны, о более глубокой интеграции белорусов в латвийское общество. Статья написана на основе архивных документов и периодической печати того времени, много информации из источников публикуется впервые. Kewords / Ключевые слова: Latvia, Latgalе, Belarusian minority, Belarusian political parties, parliamentary elections, the 3rd Saeima, the 4th Saeima / Латвия, Латгалия, белорусское меньшинство, белорусские политические партии, парламентские выборы, Третий Сейм, Четвёртый Сейм. In the 1920s and 1930s the Belarusians were one of the largest national minorities in Latvia. The majority of Belarusians lived in region of Latgale (the eastern part of Latvia) and Ilūkste Municipality (southeastern Latvia, part of Zemgale region). -

The Commercial Deals Connected with Gazprom's Nord Stream 2

The commercial deals connected with Gazprom's Nord Stream 2 A review of strings and benefits attached to the controversial Russian pipelines Anke Schmidt-Felzmann, PhD Senior Researcher at the Research Centre of the General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania Abstract This paper reviews the multiple strings and benefits attached to the single most controversial gas pipeline project in Europe - the second Russian twin subsea pipeline that is currently under construction in the Baltic Sea. While much attention has been paid to the question of why and how the Russian state- controlled energy giant seeks to circumvent Ukraine as a transit country for its delivery of gas to Western Europe, hardly any attention has been paid to the benefits gained by the companies and political entities directly involved in the preparation and construction of Nord Stream 2. The paper seeks to fill this gap in the debate by taking a closer look at the business deals and commercial actors involved in the implementation of this second Russian natural gas pipeline project in the Baltic Sea. It highlights how local and national economic interests and European energy companies' motivations for participating in the project go beyond the volumes of Russian natural gas that Gazprom expects to deliver to European customers through its Baltic Sea pipelines from 2020. Keywords: Baltic Sea, Nord Stream, Gazprom, Russia, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Latvia. This analysis was produced within the Think Visegrad Non-V4 Fellowship programme. Think Visegrad – V4 Think Tank Platform is a network for structured dialog on issues of strategic regional importance. The network analyses key issues for the Visegrad Group, and provides recommendations to the governments of V4 countries, the annual presidencies of the group, and the International Visegrad Fund.