Oman: the Gulf’S Go-Between Sigurd Neubauer Issue Paper #1 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S

Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy Updated January 27, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RS21534 SUMMARY RS21534 Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy January 27, 2020 The Sultanate of Oman has been a strategic partner of the United States since 1980, when it became the first Persian Gulf state to sign a formal accord permitting the U.S. military to use its Kenneth Katzman facilities. Oman has hosted U.S. forces during every U.S. military operation in the region since Specialist in Middle then, and it is a partner in U.S. efforts to counter terrorist groups and related regional threats. The Eastern Affairs January 2020 death of Oman’s longtime leader, Sultan Qaboos bin Sa’id Al Said, is unlikely to alter U.S.-Oman ties or Oman’s regional policies. His successor, Haythim bin Tariq Al Said, a cousin selected by Oman’s royal family immediately upon the Sultan’s death, espouses policies similar to those of Qaboos. During Qaboos’ reign (1970-2020), Oman generally avoided joining other countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, UAE, Bahrain, Qatar, and Oman) in regional military interventions, instead seeking to mediate their resolution. Oman joined the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State organization, but it did not send forces to that effort, nor did it support groups fighting Syrian President Bashar Al Asad’s regime. It opposed the June 2017 Saudi/UAE-led isolation of Qatar and did not join a Saudi-led regional counterterrorism alliance until a year after that group was formed in December 2015. -

GM ..L«»U2=U UM-H33 Casu

ROYAL NORWEGIAN EMBASSY 5*-.-94.3435‘5*-.=S1-5* U-I’--J‘ RIYADH-DQ — tLIUL§.unJ‘ UA 41441/05/24 zt-.0‘-'4‘ 92020/01/19:¢3éuA\ 2020/05/OM :5-3; MSL gmqfms,.asgmnUuamxwbuugíxgxgggàzgågíaeæymzesmwjiuméàg .2\,\_>,,,n\a_,_>,m\sfij,kgu..u^afè,fll\flej.fl\uu,gzsée,sfl\æsygmaxm dJ3---“ J93:-“ 43499oe gs:-*9 oe ~3-39/313--51‘ am 93! L§":‘JJ“‘as---S=u‘ 4-'9‘IMM” :0‘-A3"*3-‘=1-«e"‘-s+J‘$3* 0334'-“ 0° J-J3-“JW" .4:-I-w«JV-‘ea-U-C>eu-u-.I\3 oU=1--“3-D‘-ritési-.=5oJ=J‘J aw?‘ 1a,.;u\Q,é4:JuS!3Lu\,‘J\L§..ei¢51:,¢.,s:s1,s‘sM,.shi,‘9s‘Li‘s ¢§‘J'u:u\,.i.{§.;a:i ,9,.‘t...:.Js...a..':..x\,~\...,s..xsQ,:.L....\,..L§..s-.\\,.x§s:¢\;.s.;...,4.$:.1,34.,.;....x1g,:.s\ JLa.§s\,,:.\:J\4..\,':J\1:y..:.\J,;i:J4§3_i..,:;._,L.,.s;i..,c5L,.,,13¢,LLL..s\3\J>\.,¢,1s;§J 13s=;.ss‘,,A2x.sL.4..Js,?>L.4s_3,g.3s " L5-‘.-.UJ*-“deaéu‘ 4-'9‘/Saw-5‘ 43-2993;-'4‘ 3-.9354‘beis æugàmnUuaumgmgflaâumsuâaèæymaessánbmxJeg; ..L«»u2=uUM-H33 GM casu- :gun du; an.. 3,13.» s» J4‘-—-U5‘ Posta! Address Office Address Telephone: E4MaI1 P O Box 94380 Drplomatic Quarter +966 11 488 7904 [email protected] Rcyadh 11693 Riyadh Fax www.norway.no/en/saudi-arabIa/ Saudi Arabia Saudi Arabua +966 11 483 3168 ROYAL NORWEGIAN EMBASSY Ix,.+4,,,3s\3.,sJ..3ssJ1.i...J\ RIYADH-DQ üULÃuJl gå - Date: 19/01/2020 Ref: OM/05/2020 The Royal Norwegian Embassy presents its compliments to the Embassy of Sultanate of Oman in Riyadh and has the honor to convey, the following condolences message from H.E the Norwegian Minster of Foreign Affairs Ms. -

January 9, 1975 the President's Office 2:40 P.M

File scanned from the National Security Adviser's Memoranda of Conversation Collection at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON S13 SitE'£'I XGDS MEMORANDUM OF CONVERSATION PARTICIPANTS: His Majesty Qaboos bin Said, Sultan of Oman Qays Abd al-Munim Zawawi. Minister of State fo r Fo reign Affair Sayyid Tarik, Royal Advisor President Gerald R. Ford Dr. Henry A. Kissinger, Secretary of State and Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Lt. General Brent Scowcroft DATE AND TIME: Thur sday, January 9. 1975 2:30 p. m. (45 minutes) PLACE: The Oval Office The President: We are very pleased to have you here. And we are very proud of our long relationship, which was established in 1833. ~ During Andrew Jackson's presidency. I wonder how someone from the ~ hills of Kentucky could be so farsighted. ~ 0;() J I understand we have the Peace Crops in your country. What do they do? ''; e;i Sultan Qaboos: I think they are out in the field mostly. !~!:oreign Minister: They are working mostly in agriculture. ~he President: We are revising the Peace Corps program. Now it Ilincludes a lot of retired people with real skills. Previously there were 21 .a lot of people who specialized in political matters. We have stopped most _.IO! that. .~ "." " • I wa.uld appreciate your views on South Yemen and the insurgency it'S!!~ 1~ supporting. ~ I Sultan Qaboos: They have been supporting revolutionaries and terrorists. - ;:..,..../ Jt They have two schools where they train about 500 young people whom they II Ii will later infiltrate not only into Oman but elsewhere. -

Oman Succession Crisis 2020

Oman Succession Crisis 2020 Invited Perspective Series Strategic Multilayer Assessment’s (SMA) Strategic Implications of Population Dynamics in the Central Region Effort This essay was written before the death of Sultan Qaboos on 20 January 2020. MARCH 18 STRATEGIC MULTILAYER ASSESSMENT Author: Vern Liebl, CAOCL, MCU Series Editor: Mariah Yager, NSI Inc. This paper represents the views and opinions of the contributing1 authors. This paper does not represent official USG policy or position. Vern Liebl Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning, Marine Corps University Vern Liebl is an analyst currently sitting as the Middle East Desk Officer in the Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning (CAOCL). Mr. Liebl has been with CAOCL since 2011, spending most of his time preparing Marines and sailors to deploy to Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and other interesting locales. Prior to joining CAOCL, Mr. Liebl worked with the Joint Improvised Explosives Device Defeat Organization as a Cultural SME and, before that, with Booz Allen Hamilton as a Strategic Islamic Narrative Analyst. Mr. Liebl retired from the Marine Corps, but while serving, he had combat tours to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Yemen, as well as numerous other deployments to many of the countries of the Middle East and Horn of Africa. He has an extensive background in intelligence, specifically focused on the Middle East and South Asia. Mr. Liebl has a Bachelor’s degree in political science from University of Oregon, a Master’s degree in Islamic History from the University of Utah, and a second Master’s degree in National Security and Strategic Studies from the Naval War College (where he graduated with “Highest Distinction” and focused on Islamic Economics). -

A Study in Longevity

darien analytics Financial market analysis MARCH 2012 ISSUE 5 special report An Egyptian demonstrator in Tahrir Square holds up a picture of former President Gamal Abd al-Nasser Rulers or Heads of State? In the Middle East, it is usually obvious Middle East Rulers: who the rulers are even though they carry different titles: for example, King Fahd of Saudi Arabia, Sultan Qaboos of Oman, and President Bouteflika of Algeria. In all three a study in longevity of those countries there are Parliamentary bodies elected by some degree of suffrage and exercising certain levels of legislative When Ali Abdullah Saleh left Yemen for medical treatment in the U.S. in January, he became authority – but it is clear who wields the the fourth Arab leader to fall as a result of the popular uprisings in the region that began real power. in 2011. Saleh’s return from the U.S. and his formal handing over of the Presidency at a It’s not always clear. ceremony in Sana’a on 25 February couldn’t disguise the fact that he had been ousted as a result of popular protests and a loss of support from significant sections of the armed forces. The Lebanese head of state, President Michel Suleiman, has powers, both formal Saleh’s fall had been preceded by that of Mo’ammer Ghaddafi, who began losing control and informal. Like his predecessor, Emile of Libya in mid-2011 and was killed in October; Hosni Mubarak, who resigned as President Lahoud, he was previously head of the of Egypt in February; and Zeine el-Abeddine Ben Ali, who resigned as President of Tunisia army, and he is one of the key figures in January. -

NAPCO CELEBRATING OMANI NATIONAL DAY Omani National Day

MONTHLY NEWS where creativity meets quality LETTER NOVEMBER2018 INSIDE THIS ISSUE NAPCO CELEBRATING OMANI NATIONAL DAY Omani national day ................. 1 Ministries visit......................... 2 National Aluminum Product Company S.A.O.G (NAPCO) Employee of the month ........... 2 celebrated the National Day with excitement across its of- Royal state Eng. ...................... 3 fice and factory in Rusayl. Case study ............................... 3 National Day celebrates many achievements of the beloved warning.................................... 3 leader His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said, and focuses on New slogan .............................. 4 the achievements across all Omani communities and sec- Contact us ................................ 4 tors of the economy, since the commencement of the NAPCO INSIGHTS blessed Renaissance march in 1970. • NAPCO Celebrating Omani na- To mark this blessed occasion, Ihab Mouallem, chief execu- tional day. tive officer, said: “I would like to congratulate everyone on • NAPCO arranged factory visit. the 48th National Day and pray to Allah to bless our be- • Where creativity meets quality loved leader His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said with good health and long life. As NAPCO fulfilled its 3 decades of alu- minum extrusion giving highly end aluminum profiles to rise Oman flag high in all over the world and to let everyone knows Omani product that made extremely high impact in- to Oman’s economy”. MINISTRIES ENGINEERS VISIT TO NAPCO To introduce Oman’s aluminum extrusion and to make Omani product the first choice in all invest- ments, NAPCO invited engineers from different min- istries in Oman to attend a presentation about the company and to visit the factory. during the visit NAPCO CEO Mr. Ihab Mouallem highlighted the dif- ferences between abroad and local product and clari- fied all points that been asked by the visitors. -

Suddensuccession

SUDDEN SUCCESSION Examining the Impact of Abrupt Change in the Middle East SIMON HENDERSON EDITOR REUTERS Oman After Qaboos: A National and Regional Void The ailing Sultan Qaboos bin Said al-Said, now seventy-nine years old, has no children and no announced successor, with only an ambiguous mechanism in place for the family council to choose one. This study con- siders the most likely candidates to succeed the sultan, Oman’s domestic economic challenges, and whether the country’s neutral foreign policy can survive Qaboos’s passing. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY POLICY NOTE 74 DECEMBER 2019 SUDDEN SUCCESSION: OMAN In November 2019, while presiding over Oman’s TABLE 1. ILL-FATED OMANI SULTANS National Day celebration at the Wudam naval base, Thuwaini bin r. 1856–66 Killed in his sleep by his Sultan Qaboos bin Said, who has ruled his country Said son Salem bin Thuwaini for nearly five decades, looked particularly frail. It was correspondingly of little surprise that on December 7 he Salem bin r. 1866–68 Deposed by his cousin departed for Belgium to undergo a series of medical Thuwaini Azzan bin Qais tests at Leuven’s University Hospitals. In 2014–15, the Azzan bin r. 1868–71 Not recognized by British; sultan spent eight months in Germany while receiving Qais killed in battle apparently successful treatment for colon cancer. But his latest trip abroad coincided with rumors of a signifi- Taimur bin r. 1913–32 Abdicated to his son Said Faisal bin Taimur under pressure cant deterioration in his health.1 Although he has now returned to Oman, the prognosis for any seventy-nine- Said bin r. -

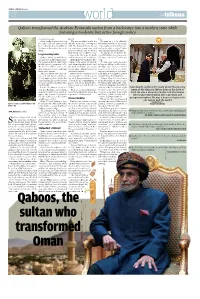

Qaboos, the Sultan Who Transformed Oman

SUNDAY, JANUARY 12, 2020 07 Qaboos transformed the Arabian Peninsula nation from a backwater into a modern state while pursuing a moderate but active foreign policy cil statement said. (GCC). 1962. State media did not disclose “He was a stable force in the He went on to join a British the cause of death. Qaboos had Middle East and a strong US infantry battalion in Germany, been ailing for years and was in ally. His Majesty had a vision returning home to bide his time Belgium in December for treat- for a modern, prosperous, and under the close watch of his fa- ment. peaceful Oman, and he willed ther, Sultan Said bin Taymur. that vision into reality,” former On July 23, 1970, Qaboos de- Longest-serving leader US president George W. Bush posed his father in a palace coup, Qaboos, who died on Friday at said in a message of condolence. pledging “a new era” for the na- the age of 79 as the longest-serv- Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mo- tion. ing leader of the modern Arab hammed bin Zayed Al-Nahyan “In the early years, he went world, came to power in 1970. said Saturday that Oman and village to village and he had a He had been ill for some time the Arab world have lost a “wise weekly radio address -- that and was believed to be suffering leader and a (figure) of great was the only way to reach the from colon cancer. historical stature”. entire population at the time,” The late sultan, who was un- British Prime Minister Boris said Muscat-based public policy married and had no children, Johnson also recalled a meet- analyst Ahmed al-Mukhaini. -

President Clinton's Meetings & Telephone Calls with Foreign

President Clinton’s Meetings & Telephone Calls with Foreign Leaders, Representatives, and Dignitaries from January 23, 1993 thru January 19, 20011∗ 1993 Telephone call with President Boris Yeltsin of Russia, January 23, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin of Israel, January 23, 1993, White House Telephone call with President Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine, January 26, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt, January 29, 1993, White House Telephone call with Prime Minister Suleyman Demirel of Turkey, February 1, 1993, White House Meeting with Foreign Minister Klaus Kinkel of Germany, February 4, 1993, White House Meeting with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney of Canada, February 5, 1993, White House Meeting with President Turgut Ozal of Turkey, February 8, 1993, White House Telephone call with President Stanislav Shushkevich of Belarus, February 9, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with President Boris Yeltsin of Russia, February 10, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with Prime Minister John Major of the United Kingdom, February 10, 1993, White House Telephone call with Chancellor Helmut Kohl of Germany, February 10, 1993, White House declassified in full Telephone call with UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali, February 10, 1993, White House 1∗ Meetings that were only photo or ceremonial events are not included in this list. Meeting with Foreign Minister Michio Watanabe of Japan, February 11, 1993, -

Isg Celebrates National Day with Zeal

ISG CELEBRATES NATIONAL DAY WITH ZEAL Indian School Al Ghubra celebrated the 46th National Day of Oman with great fanfare and fervor. The school campus adorned with flags, balloons, ribbons and streamers came alive with the vibrant colours of the flag of Oman setting the mood for the festivities. Students of Classes 6 to 8, dressed in red, white and green displayed their love and loyalty to His Majesty Sultan Qaboos Bin Said by forming the words ‘Long Live Sultan’ on the school grounds on Thursday, November 17.. A Special Assembly conducted on November 17, by the students of the senior school commenced with the singing of the Royal Anthem of Oman by the Nationals on the school staff. Speeches, presentations and a skit in Arabic enlightened students about the life and achievements of His Majesty Sultan Qaboos Bin Said, his vision and leadership which launched this country on the path of progress and prosperity. The rich cultural heritage of Oman, the natural beauty of the land and the significance of National Day was also focused upon. The highlight of the Assembly was the performance of Omani Nationals who are valued members on the school staff. Through speeches, and poems in Arabic and English they expressed their love for His Majesty Sultan Qaboos Bin Said and the special bond he has forged with his people. They also shared the pride and loyalty they feel towards their beloved land and enlightened the students about the glorious past of Oman. In his address, Mr. Ahmed Rayees, the President of the School Management Committee highlighted the remarkable progress made by Oman in all sectors be it infrastructure, education or health care. -

Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy

Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy Updated March 28, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RS21534 Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy Summary The Sultanate of Oman has been a strategic ally of the United States since 1980, when it became the first Persian Gulf state to sign a formal accord permitting the U.S. military to use its facilities. Oman has hosted U.S. forces during every U.S. military operation in the region since then, and it is a partner in U.S. efforts to counter regional terrorism and related threats. Oman’s ties to the United States are unlikely to loosen even after its ailing leader, Sultan Qaboos bin Sa’id Al Said, leaves the scene. Qaboos underwent cancer treatment abroad during 2014-2015, and his frail appearance in public appearance fuels speculation about succession. He does continue to meet with visiting leaders, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on October 25, 2018, the first such visit by Israeli leadership to Oman in more than 20 years. Oman has tended to position itself as a mediator of regional conflicts, and generally avoids joining its Gulf allies of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, UAE, Bahrain, Qatar, and Oman) in regional military interventions such as that in Yemen. Oman joined the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State organization, but it did not send forces to that effort, nor did it support groups fighting Syrian President Bashar Al Asad’s regime. It refrained from joining a Saudi-led regional counterterrorism alliance until a year after that group was formed in December 2015, and Oman opposed the June 2017 Saudi/UAE isolation of Qatar. -

Program from Ceremony for International Peace Award to His

ADDRESSFROM HIS MAJESTY SULTAN QABOOS BIN SAID We believe that when nations and cul tures, despite their differences, are able to communicate effectively with each other, they move naturally to wards peace. We believe that human kind is inherently peace loving. And so, we also believe that all, individu ally and collectively, have a sacred duty to pursue the cause of peace, and that in fulfilling this duty, we help humankind to real ize its destiny. It has been our privilege to work closely with the United States for this cause. We have worked together for more than twenty years, in the search for a just, lasting, and comprehensive peace in the Middle East. We would like to thank President Carter for honoring us by mak ing this Award. We highly value and appreciate the leadership he gave the world during his presidency. We are grateful to all of the organizations who contributed to and sponsored this Award, in particular to Dr. John Duke Anthony and the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations for their initiative. We thank you all for your recognition of our contribution to re gional and international peace. Be assured our commitment is wholehearted, and, with the gracious will of God, will endure in the face of every challenge. 2 MESSAGE FROM PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER It is a great privilege for me to present the International Peace Award to His Majesty Sultan Qaboos Bin Said. For many years, I personally have admired his courageous efforts to bring peace to his region of the world. He deserves recognition and thanks, as do the people of Oman for their support of him.