Download the Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YOUR DONATION to PHCA Ashland Bellsouth Corp

Argonaut Group. Bass, Berry and Sims, PLC Butler Manufacturing Co. Ariel Capital Management Baxter International Cadence Design Systems Aristokraft Bay Networks Calex Manufacturing Co. Arkema BEA Systems Calpine, Corp. Armstrong World Industries Bechtel Group CambridgeSoft Armtek, Corp. Becton Dickinson and Co. Campbell Soup Foundation Arrow Electronics Belden Wire and Cable Co. Canadian Pacific Railway YOUR DONATION to PHCA Ashland BellSouth Corp. Capital Group Cos. Aspect Telecommunications Bemis Co. Capital One Services Companies with Matching Gift Programs Associates Corp. of North BeneTemps Cardinal Health (contact your HR Dept. for instructions) America L.M. Berry and Co. Cargill Assurant Health BHP Minerals International Carnegie Corp. of New York Astoria Federal Savings Binney and Smith Castrol North America AAI Corp. Amerada Hess Corp. AstraZenca Bituminous Casualty Corp. Carson Products Co. Abbott Laboratories Ameren Corp. AT&T Black and Decker Corp. Catalina Marketing, Corp. ABN AMBRO North American Electric Power Atlantic City Electric Co. Blount Foundation Catepillar America American Express Co. Atlantic Data Services Blue Bell Central Illinois Light Co. Accenture American General Corp. Autodest BMC Industries Chesapeake Corp. ACF Industries American Honda Motor Corp. Automatic Data Processing BMO Financial Group, US ChevronTexaco Corp. Acuson American International Group AVAYA BOC Group Chicago Mercantile Exchange ADC Telecommunications American National Bank Avery Dennison, Corp. Boeing Co. Chicago Title and Trust Co. Addison Weley Longman American Optical Corp. Avon Products Bonneville International Corp. Chicago Tribune Co. Adobe Systems American Standard AXA Financial Borden Family of Cos. Chiquita Brands International Advanced Micro Devices American States Insurance Baker Hughes Boston Gear Chubb and Sone AEGON USA American Stock Exchange Ball Corp. -

Real Estate Sector 4 August 2015 Japan

Deutsche Bank Group Markets Research Industry Date Real estate sector 4 August 2015 Japan Real Estate Yoji Otani, CMA Akiko Komine, CMA Research Analyst Research Analyst (+81) 3 5156-6756 (+81) 3 5156-6765 [email protected] [email protected] F.I.T.T. for investors Last dance Bubbles always come in different forms With the big cliff of April 2017 in sight, enjoy the last party like a driver careening to the cliff's brink. Japan is now painted in a completely optimistic light, with the pessimism which permeated Japan after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 forgotten and expectations for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics riding high. The bank lending balance to the real estate sector is at a record high, and we expect bubble-like conditions in the real estate market to heighten due to increased investment in real estate to save on inheritance taxes. History repeats itself, but always in a slightly different form. We have no choice but to dance while the dance music continues to play. ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Deutsche Securities Inc. Deutsche Bank does and seeks to do business with companies covered in its research reports. Thus, investors should be aware that the firm may have a conflict of interest that could affect the objectivity of this report. Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. DISCLOSURES AND ANALYST CERTIFICATIONS ARE LOCATED IN APPENDIX 1. MCI (P) 124/04/2015. Deutsche Bank Group Markets Research Japan Industry Date 4 August 2015 Real Estate Real estate sector FITT Research Yoji Otani, CMA Akiko Komine, CMA Research Analyst Research Analyst Last dance (+81) 3 5156-6756 (+81) 3 5156-6765 [email protected] [email protected] Bubbles always come in different forms Top picks With the big cliff of April 2017 in sight, enjoy the last party like a driver Mitsui Fudosan (8801.T),¥3,464 Buy careening to the cliff's brink. -

Case 20-32299-KLP Doc 208 Filed 06/01/20 Entered 06/01/20 16

Case 20-32299-KLP Doc 208 Filed 06/01/20 Entered 06/01/20 16:57:32 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 137 Case 20-32299-KLP Doc 208 Filed 06/01/20 Entered 06/01/20 16:57:32 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 137 Exhibit A Case 20-32299-KLP Doc 208 Filed 06/01/20 Entered 06/01/20 16:57:32 Desc Main Document Page 3 of 137 Exhibit A1 Served via Overnight Mail Name Attention Address 1 Address 2 City State Zip Country Aastha Broadcasting Network Limited Attn: Legal Unit213 MezzanineFl Morya LandMark1 Off Link Road, Andheri (West) Mumbai 400053 IN Abs Global LTD Attn: Legal O'Hara House 3 Bermudiana Road Hamilton HM08 BM Abs-Cbn Global Limited Attn: Legal Mother Ignacia Quezon City Manila PH Aditya Jain S/O Sudhir Kumar Jain Attn: Legal 12, Printing Press Area behind Punjab Kesari Wazirpur Delhi 110035 IN AdminNacinl TelecomunicacionUruguay Complejo Torre De Telecomuniciones Guatemala 1075. Nivel 22 HojaDeEntrada 1000007292 5000009660 Montevideo CP 11800 UY Advert Bereau Company Limited Attn: Legal East Legon Ars Obojo Road Asafoatse Accra GH Africa Digital Network Limited c/o Nation Media Group Nation Centre 7th Floor Kimathi St PO Box 28753-00100 Nairobi KE Africa Media Group Limited Attn: Legal Jamhuri/Zaramo Streets Dar Es Salaam TZ Africa Mobile Network Communication Attn: Legal 2 Jide Close, Idimu Council Alimosho Lagos NG Africa Mobile Networks Cameroon Attn: Legal 131Rue1221 Entree Des Hydrocarbures Derriere Star Land Hotel Bonapriso-Douala Douala CM Africa Mobile Networks Cameroon Attn: Legal BP12153 Bonapriso Douala CM Africa Mobile Networks Gb, -

TOKYO TATEMONO GROUP CSR REPORT 2019 Index Message from the President Feature Corporate Philosophy Environmental Initiatives and CSR

TOKYO TATEMONO GROUP CSR REPORT 2019 Index Message from the President Feature Corporate Philosophy Environmental Initiatives and CSR Safety & Security Initiatives Responding to Social Change Community Involvement Utilization of Human Improving Management Resource Assets System Message from the President P3 [Editorial Policy] Tokyo Tatemono Group sees the realization of a Feature P5 sustainable society as its duty. The CSR information Feature Learn, Connect, Act Community Building through broadcast to society is for the purpose of communicating the type of initiatives that we are undertaking to all of our Creating "Spaces" P5 stakeholders. The CSR Communication Book (Booklet) is published in Group Profile P9 an easy-to-read format to target an even greater number Corporate Philosophy and CSR P10 of people. Initiatives including all data are available on our CSR website as well as CSR, which summarize our efforts of each year, and ESG Data Book, which only has data, Environment are available as PDF. To facilitate understanding from various stakeholders, Environmental Initiatives P13 Tokyo Tatemono Group selects themes considered important to society and our customers and strives Policy and System for Environmental Initiatives P13 to expand our public information items around recent Climate Change P19 examples of initiatives for those themes. Biodiversity P23 In addition, the Feature section includes initiatives distinct to the Tokyo Tatemono Group that we would like to Water Resources P24 highlight in particular to all of our stakeholders. Pollution Control and Effective Use of Resources P25 In Responding to Social Changes, recent activities that the Tokyo Tatemono Group is focusing on in response to the changing society are reported. -

Experience and Track Record in Marunouchi

Otemachi Park Building, 1-1, Otemachi 1-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8133, Japan TEL +81-3-3287-5200 http://www.mec.co.jp/ Experience and Track Record in Marunouchi 1890 The construction of the area’s first modern office Building, Mitsubishi 1900 1890s – 1950s Ichigokan, was completed in 1894. Soon after, three-story redbrick office First Phase of Buildings began springing up, resulting in the area becoming known as the 1910 “London Block.” Development Following the opening of Tokyo Station in 1914, the area was further 1890s developed as a business center. American-style large reinforced concrete 1920 Dawning of a Full-Scale Buildings lined the streets. Along with the more functional look, the area Starting from Business Center Development was renamed the “New York Block.” Scratch 1940 Purchase of Marunouchi Land and Vision of a Major Business Center 1950 As Japan entered an era of heightened economic growth, there was a sharp 1960 1960s – 1980s increase in demand for office space. Through the Marunouchi remodeling plan that began in 1959, the area was rebuilt with large-scale office buildings, providing a considerable supply of highly integrated office space. 1970 Second Phase of Sixteen such buildings were constructed, increasing the total available floor Development space by more than five times. In addition, Naka-dori Avenue, stretching 1980 An Abundance of Large-Capacity from north to south through the Marunouchi area, was widened from 13 Office Buildings Reflecting a meters to 21 meters. The 1980s marked the appearance of high-rise buildings more than 100 The history of Tokyo’s Marunouchi 1990 Period of Rapid Economic Growth meters tall in the area. -

List of Matching Gift Companies *Verify with Your HR Dept. 3M a a & B Foundation a K Steel Foundation A

List of Matching Gift Companies *Verify with your HR Dept. 3M A A & B Foundation A K Steel Foundation A. E. Stanley Manufacturing A. O. Smith Foundation AARP Abbott Laboratories ABN AMRO Accenture Access Energy Corp. ACE INA Acuity Brands Acuson Corporation A-D Electronics, Inc. Adams, Harkness & Hill, Inc. Adaptec Foundation ADC Telecommunications Adelante Capital Management, LLC Adobe Systems Inc. ADP Advance Micro Devices Advancement Programs AES Corporation Aetna Inc. AG Communication Systems Corp. AIG Matching Grants Program Air Products and Chemicals Akzo Nobel Chemicals, Inc. Albany International Corp. Albermarble Corp. Albright & Wilson Americas, Inc. Alcan Aluminum Corporation Alco Standard Corp. Alcoa Foundation Alexander & Baldwin, Inc. Alexander Haas Martin Algonquin Gas Transmission Co. Allegheny Teledyne Allegro MicroSystems Inc. Allendale Mutual Insurance Co. Alliance Capital Management, LP Alliant Techsystems Allied-Signal, Inc. Allstate Corporation Altria Group Inc. Amazon Amerada Hess Corporation American Airlines American Brands, Inc. American Broadcast Co. American Express Co. American General Corporation American Home Products Corporation American International Group Inc. American International Group, Inc. American National Bank American National Can Co. American Security Insurance Group American Standard, Inc. American Stock Exchange American Stock Exchange, Inc. Amerigroup Corporation Ameriprise Financial Ameristar Casinos Ameritech Amfac, Inc. Amgen, Inc. Amica Insurance Amoco Foundation Inc. AMP Fdn. AmSouth BanCorp. Foundation AMSTED Industries, Inc. Anadarko Petroleum Corp. Analog Devices Anchor Capital Advisors Inc. Anchor/Russell Capital Advisors Inc. Andersen Consulting Andersons Inc. Anheuser- Busch Anthem, Inc AOL Time Warner Aon Corp. Aquarion Co. Archer Daniels Midland ARCO ARCO Foundation Arco Foundation, Inc. Ares Advanced Technology Argonaut Croup Inc. Ariel Capital Management, LLC Aristech Chemical Company Aristokraft Inc. -

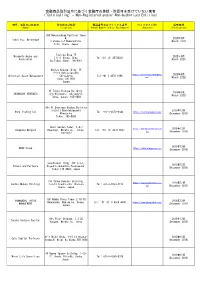

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered And/Or Non-Authorized Entities)

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered and/or Non-Authorized Entities) 商号、名称又は氏名等 所在地又は住所 電話番号又はファックス番号 ウェブサイトURL 掲載時期 (Name) (Location) (Phone Number and/or Fax Number) (Website) (Publication) 28F Nakanoshima Festival Tower W. 2020年3月 Tokai Fuji Brokerage 3 Chome-2-4 Nakanoshima. (March 2020) Kita. Osaka. Japan Toshida Bldg 7F Miyamoto Asuka and 2020年3月 1-6-11 Ginza, Chuo- Tel:+81 (3) 45720321 Associates (March 2021) ku,Tokyo,Japan. 104-0061 Hibiya Kokusai Bldg, 7F 2-2-3 Uchisaiwaicho https://universalassetmgmt.c 2020年3月 Universal Asset Management Chiyoda-ku Tel:+81 3 4578 1998 om/ (March 2022) Tokyo 100-0011 Japan 9F Tokyu Yotsuya Building, 2020年3月 SHINBASHI VENTURES 6-6 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku (March 2023) Tokyo, Japan, 102-0083 9th Fl Onarimon Odakyu Building 3-23-11 Nishishinbashi 2019年12月 Rock Trading Inc Tel: +81-3-4579-0344 https://rocktradinginc.com/ Minato-ku (December 2019) Tokyo, 105-0003 Izumi Garden Tower, 1-6-1 https://thompsonmergers.co 2019年12月 Thompson Mergers Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Tel: +81 (3) 4578 0657 m/ (December 2019) 106-6012 2019年12月 SBAV Group https://www.sbavgroup.com (December 2019) Sunshine60 Bldg. 42F 3-1-1, 2019年12月 Hikaro and Partners Higashi-ikebukuro Toshima-ku, (December 2019) Tokyo 170-6042, Japan 31F Osaka Kokusai Building, https://www.smhpartners.co 2019年12月 Sendai Mubuki Holdings 2-3-13 Azuchi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tel: +81-6-4560-4410 m/ (December 2019) Osaka, Japan. 16F Namba Parks Tower 2-10-70 YAMANASHI KYOTO 2019年12月 Nanbanaka, Naniwa-ku, Osaka, Tel: +81 (0) 6-4560-4440 https://www.ykmglobal.com/ MANAGEMENT (December 2019) Japan 8th Floor Shidome, 1.2.20 2019年12月 Tenshi Venture Capital Kaigan, Minatu-ku, Tokyo (December 2019) 6flr Nishi Bldg. -

Energy Efficiency in Buildings: Policy and Programs in Tokyo Yuko Nishida Tokyo Metropolitan Government-Environment Agenda 1

20131213 Energy Efficiency in Buildings: Policy and Programs in Tokyo Yuko Nishida Tokyo Metropolitan Government-Environment Agenda 1. Background information & Tokyo’s policy 2. Major Programs for Existing Buildings 3. Major Programs for New Buildings 4. Some Results 1. Background Information & Tokyo's Policy Energy Consump tion in Tok yo by sector Industrial Transportation 10% 24% 36% Commercial 31% Residential Emission from the Buildings Sector Tokyo’s Building Stock New Buildings (5 years or younger) 6% Existing buildings (2011) 94% Tokyo Climate Strategy TARGET 25% Reduction in GHG Emissions 20% Reduction in Energy Consumption By 2020 from the 2000 level Framework of Tokyygo Program Existing New bu ildings Larger buildings District Plan for Energy Efficiency Cap & Trade Program Building Size Green Building Program DlDevelopmen ts CO2 Emission w. incentive bonus Reporting Program Smaller Planning/Operation Stage Planning Design Construction Operation Tuning Retrofit Tokyo'sPolicyinBEE s Policy in BEE 1. Approach to Both New & Existing Buildings 2. Ratings & Disclosure 3. Utilize Ex isti ng (N ait onal) P rograms and Standards and Require Higher Performance 4. Incentivize Further Improvements Policy Development in Tokyo Plans “The 10-yr TMG environmental master plan plan” Setting sect oral targets & programs Setting the target 2000 2002 2005 2006 2008 2010 2012 Programs Climate Change Strategy Carbon Minus 10yr project Basic policy for the10yr project Action plan Reporting Program CO2 Emission Reporting program for SMEs ●2002 ●●20052005 Start ReviseIntroduce Disclosure system Tokyo Cap& Trade ●2008 ●2010 Enact Start Green Bu ilding P rogram ● ●2008 2002 ●2005 Revise Start Revise Green Labeling Program for Condominiums District Plan for Energy Efficiency 2. -

Japan-US-2009-Symposium.Pdf

SYMPOSIUM ON BUILDING THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM OF THE 21ST CENTURY: AN AGENDA FOR JAPAN AND THE UNITED STATES ARMONK, NEW YORK • OCTOBER 23-25, 2009 AGENDA FRIDAY, OCTOBER 23 5:30-6:15 Doral Guests – Bus to the Weill Center departs approximately every 15 minutes 6:00-6:30 Cocktail Reception – Main Lobby of the Weill Center 6:30-6:40 GREETINGS – Conference Room H, second floor Hal Scott, Nomura Professor and Director, Program on International Financial Systems (PIFS), Harvard Law School Tribute to Tasuku Takagaki Takashiro Furuhata, Executive Director, International House of Japan 6:40-7:40 KEYNOTE ADDRESS – Conference Room H Bill Rhodes, Senior Vice Chairman, Citi; Senior Vice Chairman, Citibank Shigesuke Kashiwagi, President and Chief Executive Officer, Nomura Holding America, Inc. 7:45-9:15 Dinner – Main Dining Room, first floor 9:15-11:00 After-Dinner Cocktails – Main Lobby 9:15 Doral Guests – Bus to the Doral; meet in Main Lobby 10:00 Doral Guests – Bus to the Doral; meet in Main Lobby 11:00 Doral Guests – Last bus to the Doral; meet in Main Lobby SATURDAY, OCTOBER 24 7:00-8:00 Doral Guests – Bus to the Weill Center departs approximately every 15 minutes 7:30-8:15 Breakfast – Main Dining Room Panelists, Reporters, and Facilitators – Breakfast Meeting in Main Dining Room 8:15-8:25 WELCOME & OPENING REMARKS – Conference Room H Hal Scott, Nomura Professor and Director, Program on International Financial Systems (PIFS), Harvard Law School 1 8:25-8:45 PANEL SESSION – Conference Room H Topic 1: The Future of Banking and Securities Regulation Japan Panelist: Nobuchika Mori, Deputy Commissioner, International Affairs and Supervision, Financial Services Agency, Government of Japan U.S. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 ANNUAL REPORT 2010 | 21 Building Business

Business Information Business Structure of the Mitsubishi Estate Group Maximize asset Risk Funds Real estate Building Business efficiency management procurement investment Urban Development & Residential Business Investment Management Determine Conduct Consider Real estate-related Customers current research initiatives planning, International Business Mitsubishi Estate Architectural Design & Co., Ltd. Engineering status and analysis and proposals proposals and services Custom-Built Housing Hotel Business Proposal determination Real Estate Services Implementation Consolidated Analysis and review Business Segment Group Framework Business Activities Sales Breakdown Building Business • Property Management and Office Leasing Building Business segment revenues are derived mainly Group from building development and leasing in Japan. This • Commercial Asset Management and Develop- segment is also engaged in building management, ment Group parking facilities, district heating and cooling, and ¥489.6 47.4% • Retail Property Group other operations. Billion Real estate development Real estate investment Real estate liquidity Building operation and Comprehensive building Construction Design and supervision CRE strategy support • Development method • Real estate investment • Real estate-backed management analysis • Single-unit homes • Environmental assessment • Organization of CRE proposals strategy formulation support financing support • Operation and management plan • Earthquake resistance and rental and and research information • Business plan support -

Initiatives for Supporting Urban Development Overseas by Private Companies

Initiatives for supporting Urban Development Overseas by Private Companies Toru ISHIKAWA, Director, International Affairs Office, City Bureau, MLIT Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism 1. Promotion of Overseas Expansion of Infrastructure Systems 2. Experiences in Japanese Urban Development 3. Japanese Initiatives 4. Japan Overseas Infrastructure Investment Corporation for Transport & Urban Development (JOIN) 5. Examples of Current Policies 6. Next Steps 1. Promotion of Overseas Expansion of Infrastructure Systems • In accordance with the Prime Minister’s directives in March 2013, the “Economic Infrastructure Strategy Committee” was established with the Chief Cabinet Secretary as chairman to comprehensively debate infrastructure export, economic assistance, etc. • The “Infrastructure Systems Export Strategy” was determined at an Economic Assistance Infrastructure Strategy Meeting in May of that same year. The goal result was set as orders of about ¥30 trillion in 2020 (about ¥10 trillion in 2010). As we promote the Five Pillars of Concrete Strategy below, we carry out active top-level sales by the Prime Minister, cabinet ministers, etc. <Five Pillars of Concrete Strategy (policy system for infrastructure system export strategy) > 1. Promotion of public-private partnerships for strengthening enterprises’ global competitiveness 2. Support for discovery/cultivation of enterprises/local governments and talent that can carry overseas expansion of infrastructure forward 3. Acquisition of international standards utilizing advanced -

Integrated Report 2019

Otemachi Park Building, 1-1, Otemachi 1-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8133, Japan http://www.mec.co.jp/index_e.html MITSUBISHI ESTATE CO., LTD. Integrated Report 2019 Report Integrated LTD. CO., MITSUBISHI ESTATE Advancing Innovation, Unlocking Potential Integrated Report 2019 This report is printed using paper that contains This report has been prepared using 100% raw materials certified by the Forest vegetable ink. Every effort is made to Stewardship Council (FSC®). FSC® certification contain the incidence of volatile organic ensures that materials have been harvested compounds (VOCs) and to preserve from properly managed forests. petroleum resources. Printed in Japan WorldReginfo - 9b940c6b-cea5-49fd-a84f-5fb8403d01d6 MEC_AR19E_CV_0822_2nd.indd 1-2 2019/08/23 10:16 P2 ABOUT THE MITSUBISHI ESTATE GROUP P69 FINANCIAL SECTION 2 Track Record of Mitsubishi Estate 69 Japan’s Real Estate Market 4 Marunouchi Today 70 Eleven-Year Summary of Selected Financial Data 6 The Marunouchi Area Going Forward (Consolidated) 8 Mitsubishi Estate’s Value Creation Model 72 Financial Review 10 Business Segments 78 Consolidated Balance Sheets 80 Consolidated Statements of Income / Consolidated P12 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Statements of Comprehensive Income 81 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Net Assets P18 SPECIAL FEATURE 83 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows Urban Development of Mitsubishi Estate for 84 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements “A Love for People. Improving Corporate Value 107 Independent Auditor’s Report 20 SPECIAL FEATURE 1: