Stafford V. Rite Aid Corp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cans for Cash

A Quarterly Newsletter of The City of Irvine (949) 724-7669 Waste Management of Orange County (949) 642-1191 ® Fall 2009 Cans for Cash Put a little green in During 2007 and 2008, the City of Irvine Halloween partnered with Irvine Unified School District and local businesses to take part The origins of the Halloween tradition in a nationwide aluminum can recycling started hundreds of years ago as an ancient challenge. Through this community Celtic festival that marked the end of partnership, the City of Irvine won an award summer harvest and the beginning of two years in a row for the most innovative winter. During this celebration, they would campaign and donated the award proceeds, adorn themselves in costumes and tell each totaling $10,000, to the Irvine Public other’s fortunes. Schools Foundation to support the school Today, many of us participate in district’s recycling program. Halloween celebrations and adorn ourselves This year, the City is participating in in costumes. But instead of fortune-telling, the recycling challenge once again. So, we head out for a bounty of candy or for please save your aluminum cans and recycle a lively party. Halloween has become them in Irvine during the month of October. the second biggest holiday season of the For more information about the year, with over $5 billion in annual sales, Cans for Cash contest, please visit www. according to the National Retail Federation. cityofirvine.org/environmentalprograms or This year, help make Halloween more call (949) 724-6459. environmentally friendly. Here are some tips to add a little green to your orange and black celebrations and help save some money in the process. -

Table of Contents Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 annual general merchandise programs (cont’d): TOPIC: Walk-Around (GM Only) Program.................................................................................................................... 38 Introduction........................................................................................................................................................4 Pharmacy Checkstand (Hearing Aid Battery) Program............................................................................... 39 Promotional Fixture Review...............................................................................................................................5-19 Checkstand Side Wings (Magazine) Program................................................................................................40 Marketing Signage / Graphics Submission.....................................................................................................20 Checkstand On-Counter (Magazine) Program..............................................................................................41 2020 Profit Plan Schedule..................................................................................................................................21 Walk-Around (Magazine) Program...................................................................................................................42 2020 New Item Submission Schedule.............................................................................................................. 22 Cosmetic (Magazine) -

( Is the Leading Provider of Secure Cell P

Media Contacts: Feintuch Communications Bennie Sham / Rick Anderson / Henry Feintuch (212) 808-4903 / (718) 986-1596 / (212) 808-4901 [email protected] ChargeItSpot Corporate Fact Sheet Company Overview ChargeItSpot (www.chargeitspot.com) is the leading provider of secure cell phone charging stations for retail chains, luxury retailers, casinos, hospitals, shopping centers/malls, universities, stadiums and other indoor public venues. Founded in 2011 by Douglas Baldasare, a Wharton MBA and passionate entrepreneur, ChargeItSpot addresses a constant and critical need shared by millions of consumers every day – running out of “juice” due to a low battery and no place to charge their phones. ChargeItSpot provides free, secure and easy-to-use charging stations that can charge eight phones at a time. For retailers like Neiman Marcus, Under Armour, Nordstrom and Staples, ChargeItSpot charging stations are an innovative way to provide a much appreciated convenience for their customers while serving as a traffic and sales generator for their stores. In fact, a recent study conducted by GfK, a trusted international market research firm, found that the installation of ChargeItSpot charging stations in one retail chain brought numerous benefits to participating retail stores. The study found a 54 percent conversion rate of customers making a purchase while charging their phone, a 115 percent increase in customer in-store dwell time and a 29 percent increase in the value of each transaction. The GfK study estimated that ChargeItSpot stations generated an approximate $80,000 annual lift per unit. A significant part of ChargeItSpot’s appeal to brands, retailers and other venue owners, is the ability to fully customize the kiosk including the exterior wrap, and the touch screen interface – creating an innovative consumer engagement platform for branded messages and sponsorships. -

Usef-I Q2 2021

Units Cost Market Value U.S. EQUITY FUND-I U.S. Equities 88.35% Domestic Common Stocks 10X GENOMICS INC 5,585 868,056 1,093,655 1ST SOURCE CORP 249 9,322 11,569 2U INC 301 10,632 12,543 3D SYSTEMS CORP 128 1,079 5,116 3M CO 11,516 2,040,779 2,287,423 A O SMITH CORP 6,897 407,294 496,998 AARON'S CO INC/THE 472 8,022 15,099 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 24,799 2,007,619 2,874,948 ABBVIE INC 17,604 1,588,697 1,982,915 ABERCROMBIE & FITCH CO 1,021 19,690 47,405 ABIOMED INC 9,158 2,800,138 2,858,303 ABM INDUSTRIES INC 1,126 40,076 49,938 ACACIA RESEARCH CORP 1,223 7,498 8,267 ACADEMY SPORTS & OUTDOORS INC 1,036 35,982 42,725 ACADIA HEALTHCARE CO INC 2,181 67,154 136,858 ACADIA REALTY TRUST 1,390 24,572 30,524 ACCO BRANDS CORP 1,709 11,329 14,749 ACI WORLDWIDE INC 6,138 169,838 227,965 ACTIVISION BLIZZARD INC 13,175 839,968 1,257,422 ACUITY BRANDS INC 1,404 132,535 262,590 ACUSHNET HOLDINGS CORP 466 15,677 23,020 ADAPTHEALTH CORP 1,320 39,475 36,181 ADAPTIVE BIOTECHNOLOGIES CORP 18,687 644,897 763,551 ADDUS HOMECARE CORP 148 13,034 12,912 ADOBE INC 5,047 1,447,216 2,955,725 ADT INC 3,049 22,268 32,899 ADTALEM GLOBAL EDUCATION INC 846 31,161 30,151 ADTRAN INC 892 10,257 18,420 ADVANCE AUTO PARTS INC 216 34,544 44,310 ADVANCED DRAINAGE SYSTEMS INC 12,295 298,154 1,433,228 ADVANCED MICRO DEVICES INC 14,280 895,664 1,341,320 ADVANSIX INC 674 15,459 20,126 ADVANTAGE SOLUTIONS INC 1,279 14,497 13,800 ADVERUM BIOTECHNOLOGIES INC 1,840 7,030 6,440 AECOM 5,145 227,453 325,781 AEGLEA BIOTHERAPEUTICS INC 287 1,770 1,998 AEMETIS INC 498 6,023 5,563 AERSALE CORP -

Rite Aid Members Stand Strong Together!

Fall 2018 Rite Aid members stand strong together! Nomination of Officers: Official notice on page 15 Thanksgiving Contents Nov. 22, 23 Union President’s Report Union Representative’s Report offices Christmas Labor History Series introduction Surviving social media Dec. 24, 25 3 11 closed: New Year’s Day What’s Happening MAP Jan 1, 2019 4 Retirements, marriages, births 12 Donate blood/Alcohol awareness Negotiations Update Trust Fund Scholarship Rite Aid members reject co. offer Congratulations recipients! Next Quarterly 5 13 Membership Meetings: Rosie’s Corner News from Other Places 6 Women candidates run on courage Dodger Dogs now UNION! Wednesday, Sept. 26, 2018 14 Wednesday, Dec. 19, 2018 Reflections on Labor Day Official Notice Local 1167 Scholarship Winners Nominations of union officers Meetings start at 7 p.m. 7 15 New Member meetings are also held Labor History Series ON THE COVER: monthly at 10 a.m. and 5:30 p.m. at: Former President Bill Brooks Members at UFCW Local 1167 Auditorium 8 recalls ‘family’ strength 855 W. San Bernardino Ave. Rite Aid 5717, Riverside Bloomington, CA 92316 MAP NEW MEMBER DESERT EDGE MEETINGS Joe Duffle Here to help Editor MEMBERSHIP ASSISTANCE PROGRAM Are you a new member of Official quarterly publication of UFCW Local 1167? Has one of your Local 1167, United Food and If you have problems Health Management Center co-workers recently joined our union? Commercial Workers International Union with : Alcohol, drugs, any time, day or night, Get up to a $65 credit toward your Serving San Bernardino, Riverside and children & adolescents, 24 hours a day, Imperial Counties, California. -

Albertsons and Rite Aid to Merge in the Latest Move to Contrast the Growing Threat Posed by Online E-Commerce

Find our latest analyses and trade ideas on bsic.it Albertsons and Rite Aid to merge in the latest move to contrast the growing threat posed by online e-commerce Rite Aid (NYSE:RAD) – market cap as of 23/02/2018: $2.22bn Introduction On the 20th February, Rite Aid Corporation, one of the leading US drugstore chains, entered into a definitive merger agreement with Albertsons Companies, one of the largest American private equity-backed grocery retailers. The deal will result in the creation of a company with a combined enterprise value of c. $24bn and expected revenues of $83bn this year. Besides being part of the recent wave of consolidation characterizing the drug retailing sector, the deal can also be interpreted as a clear move against the potential entry of Amazon in the industry. About Rite Aid Corporation Rite Aid is a drugstore network and benefits-management group founded in 1968 and headquartered in Pennsylvania. The company operates approximately 4,560 stores in over 30 states across the United States and mainly operates in two segments: Retail Pharmacy and Pharmacy Services. The Retail Pharmacy segment sells brand and generic prescription drugs, as well as an assortment of front-end products. Moreover, through the two subsidiaries RediClinic and Health Dialog, it operates retail clinics and provides health coaching and healthcare analytics. The Pharmacy Services segment provides a range of transparent and traditional pharmacy benefit management (PBM) options through its EnvisionRx subsidiary and MedTrak PBMs. The company’s performance highlights a P/E ratio of 20x, aligned to the industry benchmark of 20.8x according to Reuters, and an EBITDA margin of 2.7% in FYE17. -

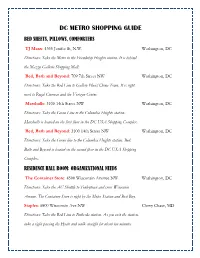

Dc Metro Shopping Guide Bed Sheets, Pillows, Comforters

DC METRO SHOPPING GUIDE BED SHEETS, PILLOWS, COMFORTERS TJ Maxx: 4350 Jenifer St, N.W. Washington, DC Directions: Take the Metro to the Friendship Heights station. It is behind the Mazza Gallerie Shopping Mall. Bed, Bath and Beyond: 709 7th Street NW Washington, DC Directions: Take the Red Line to Gallery Place/China Town. It is right next to Regal Cinemas and the Verizon Center. Marshalls: 3100 14th Street NW Washington, DC Directions: Take the Green Line to the Columbia Heights station. Marshalls is located on the first floor in the DC USA Shopping Complex. Bed, Bath and Beyond: 3100 14th Street NW Washington, DC Directions: Take the Green line to the Columbia Heights station. Bed, Bath and Beyond is located on the second floor in the DC USA Shopping Complex. RESIDENCE HALL ROOM: ORGANIZATIONAL NEEDS The Container Store: 4500 Wisconsin Avenue NW Washington, DC Directions: Take the AU Shuttle to Tenleytown and cross Wisconsin Avenue. The Container Store is right by the Metro Station and Best Buy. Staples: 6800 Wisconsin Ave NW Chevy Chase, MD Directions: Take the Red Line to Bethesda station. As you exit the station, take a right passing the Hyatt and walk straight for about ten minutes. Staples will be to your right. Staples: 3100 14th Street NW Washington, DC Directions: Take the Green Line to the Columbia Heights station. Staples is located in the DC USA Shopping Complex. APPLIANCES (RADIOS, CLOCKS, PHONES, COMPUTERS) Best Buy: 4500 Wisconsin Avenue NW Washington, DC Directions: Take the AU Shuttle to Tenleytown and cross Wisconsin Avenue. Best Buy is right by the Metro Station and The Container Store. -

Oregon Redemption Centers Albany Beaverton

Oregon Redemption Centers and Associated Retailers (5,000 or more sq ft in size) ZONE 1 ZONE 2 EXEMPT** DEALER REDEMPTION CENTERS*** FULL SERVICE PARTICIPATING RETAILERS PARTICIPATING RETAILERS (accept 144 containers) (accept 24 containers) REDEMPTION CENTERS (accept 0 containers) (accept 24 containers) 0 - 2.0 miles radius Albany from redemption center No Zone 2 Zone 1 No Zone 2141 Santiam Hwy SE Albany Grocery Outlet Albany East Liquor Store 1103 ALOHA 1950 14th Ave SE 2530 Pacific Blvd SE Albertsons #3557 approved 6/18/2015 Big Lots #4660 Dollar Tree #1508 6055 SW 185th 2000 14th Ave SE, Ste 102 1307 Waverly Dr SE Bi-Mart #606 Lowe's #3057 BEAVERTON 2272 Santiam Hwy 1300 9th Ave SE Fred Meyer #482 Costco #0682 15995 SW Walker Rd 3130 Killdeer Ave SE Fred Meyer #005 CANBY 2500 Santiam Blvd Fred Meyer #651 North Albany Market 1401 SE 1st Ave 621 NE Hickory Rite Aid #5365 Safeway #2604 1235 Waverly Dr SE 1051 SW 1st Ave Safeway #1659 1990 14th Ave SE CLACKAMAS Target #T609 Fred Meyer #063 2255 14th Ave SE 16301 SE 82nd Dr Walgreens #6530 1700 Pacific Blvd SE DALLAS Walmart #5396 Safeway #4404 1330 Goldfish Farm SE 138 W Ellendale Ave Wheeler Dealer 1740 SE Geary St EUGENE Winco Foods Fred Meyer #325 (Santa Clara) 3100 Pacific Blvd SE 60 Division St 0 - 2.0 miles radius 2.01 - 2.8 miles radius Beaverton from redemption center from redemption center Either Zone FLORENCE 9307 SW Beaverton-Hillsdale Hwy Albertsons #505 99 Ranch Cost Plus World Market #6060 Fred Meyer #464 5415 SW Beaverton Hillsdale Hwy 8155 SW Hall Blvd 10108 SW Washington -

MM Russell 2000® Small Cap Index Fund Northern Trust

Fund Holdings As of 06/30/2021 MM Russell 2000® Small Cap Index Fund Northern Trust Fund Shares or Par Position Market Security Name Ticker CUSIP Weighting (%) Amount Value ($) E-Mini Russ 2000 Sep21 Xcme 20210917 0 0 1.07 1,600 3,692,480 AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc Class A AMC 00165C104 0.75 45,428 2,574,859 Fixed Inc Clearing Corp.Repo 0 0 0.58 2,000,940 2,000,940 United States Treasury Bills 0% 0 9127963S6 0.33 1,155,000 1,154,981 Intellia Therapeutics Inc NTLA 45826J105 0.33 7,125 1,153,609 Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals Inc ARWR 04280A100 0.27 11,305 936,280 Ovintiv Inc OVV 69047Q102 0.27 29,240 920,183 Lattice Semiconductor Corp LSCC 518415104 0.25 15,140 850,565 II-VI Inc IIVI 902104108 0.25 11,668 846,980 Crocs Inc CROX 227046109 0.24 7,205 839,527 Scientific Games Corp Ordinary Shares SGMS 80874P109 0.24 10,727 830,699 Staar Surgical Co STAA 852312305 0.23 5,244 799,710 Denali Therapeutics Inc DNLI 24823R105 0.23 10,147 795,931 Tenet Healthcare Corp THC 88033G407 0.23 11,847 793,631 Fate Therapeutics Inc FATE 31189P102 0.23 8,943 776,163 Silicon Laboratories Inc SLAB 826919102 0.22 4,955 759,354 Pacific Biosciences of California Inc PACB 69404D108 0.22 21,690 758,499 Upwork Inc UPWK 91688F104 0.22 13,009 758,295 Invitae Corp NVTA 46185L103 0.22 22,351 753,899 Texas Roadhouse Inc TXRH 882681109 0.22 7,810 751,322 EMCOR Group Inc EME 29084Q100 0.22 6,037 743,698 HealthEquity Inc HQY 42226A107 0.21 9,125 734,380 Tetra Tech Inc TTEK 88162G103 0.21 6,015 734,071 Fox Factory Holding Corp FOXF 35138V102 0.21 4,712 733,470 BridgeBio Pharma -

Who's Minding the Store?

AWho’s report card on Minding retailer actions to the eliminate Store? toxic chemicals The fifth annual Who’s Minding the Store? or plastics or improving their retailer report card shows that the largest retailers chemical policies. This progress in the United States and Canada continue to is impressive given the chal- make substantial progress towards reducing and lenges of 2020 and the ongoing eliminating toxic chemicals and offering safer, impacts of a global pandemic. more sustainable products and packaging. These retail sustainability actions are preventing toxic The group of 11 retailers first pollution of communities, workers, homes, water, graded in 2016 achieved the food, people, and wildlife. greatest increase in average grade, moving from a D+ to a B-. Fifty major retailers were evaluated this year, up from 43 in 2019. Together, these retailers have This year’s report card more than 200,000 stores across the United States had the lowest-ever and Canada. percentage of retailers with failing grades. Significant Progress In 2018, nearly half of the retailers received failing grades. by Many Retailers health inequities from chemicals in beauty The failure rate dropped to nearly one-third in 2019 Companies are implementing more com- products marketed to women of color. and again to one-quarter this year. Four retailers prehensive chemical policies and achieving climbed out of the hole in 2021, erasing their pre- The beauty and personal care sector reported among greater reductions over the last five years. vious F with an improved grade: McDonald’s, TJX, the greatest gains of any retail sector. Ulta Beauty Out of the 43 retailers graded previously, near- Ulta Beauty, and Yum! Brands. -

GAME on Drug Stores Battle to Compete with Amazon | Bill Pedersen

GAME ON Drug Stores Battle to Compete with Amazon | Bill Pedersen Over the past couple of years, the retail sector has seen significant changes. With the Amazon threat now looming over the pharmacy industry, we’ve seen mergers and acquisitions heavily increase to compete with the e- commerce giant. According to leading research, the drug store industry generates $271 billion in annual revenue with retailers CVS, Walgreens, and Rite Aid capturing a significant amount of the market share. Matthews™ reviews the top three drugstore unions recently made in the sector, where Amazon stands between them, and what investors should expect from this activity. ANALYTICS MEETS HUMAN TOUCH: CVS ACQUIRES AETNA In December 2017, CVS experience, putting people CVS would now be equipped announced a merger, under at the center of health care with the capability to collect which CVS Health would acquire delivery to ensure they have massive amounts of consumer all outstanding shares of Aetna access to high-quality, more data and develop highly for a combination of cash and affordable care where they are, targeted recommendations for stock. The transaction values when they need it,” said Larry individuals based on previous Aetna at approximately $207 per Merlo, CVS Health president purchase patterns or that share or $69 billion. Including and CEO in the company’s press of similar customer profiles. the assumption of Aetna’s release. “At the same time, Intermixing this consumer data debt, the total value of the our company will benefit from not only allows a -

Revised 9/17/16

RITE AID MARKETING RESOURCES TOOL KIT FY2019 Confidential and Proprietary - ©2018 Rite Aid Corporation RevisedREV 9/17/16 8/28/17 Introduction We value your partnership and understand the importance of working collaboratively to achieve our goals, and yours. Collaboration starts with understanding the framework in which you may work. In this tool kit, we have provided the information you need to understand how to best promote your brand within the programs and services Rite Aid offers, including: • our customer brand promise • Rite Aid marketing focus areas and the innovation we strive toward • the channels available to you to optimize promotional and business planning with Rite Aid • the people you should work with in the marketing department to leverage these channels • the process you should follow to create a collaborative program with Rite Aid • 3rd Party Partner tools that may be leveraged within Rite Aid We look forward to working with you in FY’19 to develop new and innovative programs and to build your brand at Rite Aid. Confidential and Proprietary - ©2018 Rite Aid Corporation The Rite Aid Brand Our Brand Promise Rite Aid’s brand promise is to actively work with our customers to keep them well. From the Front End to the Pharmacy, everything we do is focused on supporting and enabling customers as they take steps on their individual path toward wellness. By providing the best products, unique programs and customized services, we help empower our customers to take an active role in the health of their family. How Rite Aid Actively Works with Our Customers • It’s that extra something we give our customers every single day.