Goat Farming and the Phenomenon of Theft in Menoua Division in the Western Region of Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

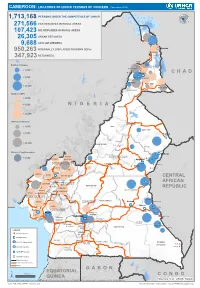

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Mountain Resources Expliotation For

International Journal of Geography and Régional Planning Research Vol.1,No.1,pp.1-12, March 2014 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) MONTANE RESOURCES EXPLOITATION AND THE EMERGENCE OF GENDER ISSUES IN SANTA ECONOMY OF THE WESTERN BAMBOUTOS HIGHLANDS, CAMEROON Zephania Nji FOGWE Department of Geography, Box 3132, F.L.S.S., University of Douala ABSTRACT: Highlands have played key roles in the survival history of humankind. They are refuge heavens of valuable resources like fresh water endemic floral and faunal sanctuaries and other ecological imprints. The mountain resource base in most tropical Africa has been mined rather than managed for the benefit of the low-lying areas. The world over an appreciable population derives its sustenance directly from mountain resources and this makes for about one-tenth of the world’s poorest.The Western highlands of Cameroon are an archetypical territory of a high population density and an economically very active population. The highlands are characterised by an ecological fragility and a multi-faceted socio-economic dynamism at varied levels of poverty, malnutrition and under employment, yet about 80 percent of the Santa highlands’ population depends on its natural resource base of vast fertile land, fresh water and montane refuge forest for their livelihood. KEYWORDS: Montane Resources, Gender Issues, Santa Economy, Western Bamboutos, Cameroon INTRODUCTION The volcanic landscape on the western slopes of the Bamboutos mountain range slopes to the Santa Highlands is an area where agriculture in the form of crop production and animal rearing thrives with remarkable success. Arabica coffee cultivation was in extensive hectares cultivated at altitudes of about 1700m at the Santa Coffee Estate at Mile 12 in the 1970s and 1980s. -

Characterisation of Fungi of Stored Common Bean Cultivars Grown in Menoua Division, Cameroon

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.31.363184; this version posted November 1, 2020. The copyright holder has placed this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) in the Public Domain. It is no longer restricted by copyright. Anyone can legally share, reuse, remix, or adapt this material for any purpose without crediting the original authors. CHARACTERISATION OF FUNGI OF STORED COMMON BEAN CULTIVARS GROWN IN MENOUA DIVISION, CAMEROON TEH EXODUS AKWA*1, JOHN M MAINGI1, JONAH K. BIRGEN2 *Corresponding author: TEH EXODUS AKWA 1Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Biotechnology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya 2Department of Plant Sciences, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya *Corresponding author: [email protected]; Tel.: +254 792 775729; Medical Microbiology, Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Biotechnology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya, P.O BOX 43844-00100-NAIROBI 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.31.363184; this version posted November 1, 2020. The copyright holder has placed this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) in the Public Domain. It is no longer restricted by copyright. Anyone can legally share, reuse, remix, or adapt this material for any purpose without crediting the original authors. CHARACTERISATION OF FUNGI OF STORED COMMON BEAN CULTIVARS GROWN IN MENOUA DIVISION, CAMEROON. Abstract Common bean is a legume grown globally especially in developing countries including Cameroon for human consumption. In Cameroon it is grown in a wide variety of agro ecological zones in quantities enough to last through the off growing season after harvest. Stored common bean after harvest in Cameroon are prone to fungal spoilage which contributes to post harvest losses. -

Back Grou Di Formatio O the Co Servatio Status of Bubi Ga Ad We Ge Tree

BACK GROUD IFORMATIO O THE COSERVATIO STATUS OF BUBIGA AD WEGE TREE SPECIES I AFRICA COUTRIES Report prepared for the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO). by Dr Jean Lagarde BETTI, ITTO - CITES Project Africa Regional Coordinator, University of Douala, Cameroon Tel: 00 237 77 30 32 72 [email protected] June 2012 1 TABLE OF COTET TABLE OF CONTENT......................................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................................... 4 ABREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................. 5 ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................... 6 0. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................10 I. MATERIAL AND METHOD...........................................................................................11 1.1. Study area..................................................................................................................11 1.2. Method ......................................................................................................................12 II. BIOLOGICAL DATA .....................................................................................................14 2.1. Distribution of Bubinga and Wengé species in Africa.................................................14 -

Full Text Article

SJIF Impact Factor: 3.458 WORLD JOURNAL OF ADVANCE ISSN: 2457-0400 Alvine et al. PageVolume: 1 of 3.21 HEALTHCARE RESEARCH Issue: 4. Page N. 07-21 Year: 2019 Original Article www.wjahr.com ASSESSING THE QUALITY OF LIFE IN TOOTHLESS ADULTS IN NDÉ DIVISION (WEST-CAMEROON) Alvine Tchabong1, Anselme Michel Yawat Djogang2,3*, Michael Ashu Agbor1, Serge Honoré Tchoukoua1,2,3, Jean-Paul Sekele Isouradi-Bourley4 and Hubert Ntumba Mulumba4 1School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon. 2School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon. 3Laboratory of Microbiology, Université des Montagnes Teaching Hospital; Bangangté, Cameroon. 4Service of Prosthodontics and Orthodontics, Department of Dental Medicine, University of Kinshasa, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Received date: 29 April 2019 Revised date: 19 May 2019 Accepted date: 09 June 2019 *Corresponding author: Anselme Michel Yawat Djogang School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon ABSTRACT Oral health is essential for the general condition and quality of life. Loss of oral function may be due to tooth loss, which can affect the quality of life of an individual. The aim of our study was to evaluate the quality of life in toothless adults in Ndé division. A total of 1054 edentulous subjects (partial, mixed, total) completed the OHIP-14 questionnaire, used for assessing the quality of life in edentulous patients. Males (63%), were more dominant and the ages of the patients ranged between 18 to 120 years old. Caries (71.6%), were the leading cause of tooth loss followed by poor oral hygiene (63.15%) and the consequence being the loss of aesthetics at 56.6%. -

Cameroon Watershed

Journal(of(Materials(and(( J. Mater. Environ. Sci., 2018, Volume 9, Issue 11, Page 3094-2104 Environmental(Sciences( ISSN(:(2028;2508( CODEN(:(JMESCN( http://www.jmaterenvironsci.com! Copyright(©(2018,( University(of(Mohammed(Premier(((((( (Oujda(Morocco( A typological study of the physicochemical quality of water in the Menoua- Cameroon watershed Santsa Nguefack Charles Vital1*, Ndjouenkeu Robert1, Ngassoum Martin Benoit2 , 1Laboratory of Food Physicochemistry, Department of Food Science and Nutrition National Advanced School of Agro- Industrial Sciences, University of Ngaoundéré, PO BOX 455,Ngaoundéré, Cameroon. 2Department of Industrial Chemistry and Environment, National Advanced School of Agro-Industrial Sciences, University of Ngaoundéré, PO BOX 455, Ngaoundéré, Cameroon. Received 29 Oct 2017 Abstract Revised 25 Dec 2018 Cameroon, a country in Central Africa with an outlet to the Atlantic Ocean in the Gulf Accepted 28 Dec 2018 of Guinea, holds enormous potentialities of water resources. These resources used for the supply of water for human consumption, etc., would be polluted by the Keywords intensification of anthropogenic activities, of which the most important recorded in the !!physicochemical, Menoua watershedof West Cameroon are agriculture and breeding. The objective of this !!pollution, work was to study the spatiotemporal parameters of the physicochemical quality !!Menoua watershed, parameters (temperature, pH, electrical conductivity, Turbidity, Nitrates, Ortho !!Anthropogenic Phosphates, Sulphates, Chloride, Potassium and Calcium) the Menoua activities, watershedthrough a main Principal Component Analysis (ACP). The results obtained showed that the pH, turbidity and orthophosphate have levels which are in contradiction !!Water for human consumption. with WHO standards. The physicochemical parameters of this water showed significant spatial and seasonal variations, the causes of which probably related to the human activities generating pollutants. -

An Inventory of Short Horn Grasshoppers in the Menoua Division, West Region of Cameroon

AGRICULTURE AND BIOLOGY JOURNAL OF NORTH AMERICA ISSN Print: 2151-7517, ISSN Online: 2151-7525, doi:10.5251/abjna.2013.4.3.291.299 © 2013, ScienceHuβ, http://www.scihub.org/ABJNA An inventory of short horn grasshoppers in the Menoua Division, West Region of Cameroon Seino RA1, Dongmo TI1, Ghogomu RT2, Kekeunou S3, Chifon RN1, Manjeli Y4 1Laboratory of Applied Ecology (LABEA), Department of Animal Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Dschang, P.O. Box 353 Dschang, Cameroon, 2Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture and Agronomic Sciences (FASA), University of Dschang, P.O. Box 222, Dschang, Cameroon. 3 Département de Biologie et Physiologie Animale, Faculté des Sciences, Université de Yaoundé 1, Cameroun 4 Department of Biotechnology and Animal Production, Faculty of Agriculture and Agronomic Sciences (FASA), University of Dschang, P.O. Box 222, Dschang, Cameroon. ABSTRACT The present study was carried out as a first documentation of short horn grasshoppers in the Menoua Division of Cameroon. A total of 1587 specimens were collected from six sites i.e. Dschang (265), Fokoue (253), Fongo – Tongo (267), Nkong – Ni (271), Penka Michel (268) and Santchou (263). Identification of these grasshoppers showed 28 species that included 22 Acrididae and 6 Pyrgomorphidae. The Acrididae belonged to 8 subfamilies (Acridinae, Catantopinae, Cyrtacanthacridinae, Eyprepocnemidinae, Oedipodinae, Oxyinae, Spathosterninae and Tropidopolinae) while the Pyrgomorphidae belonged to only one subfamily (Pyrgomorphinae). The Catantopinae (Acrididae) showed the highest number of species while Oxyinae, Spathosterninae and Tropidopolinae showed only one species each. Ten Acrididae species (Acanthacris ruficornis, Anacatantops sp, Catantops melanostictus, Coryphosima stenoptera, Cyrtacanthacris aeruginosa, Eyprepocnemis noxia, Gastrimargus africanus, Heteropternis sp, Ornithacris turbida, and Trilophidia conturbata ) and one Pyrgomorphidae (Zonocerus variegatus) were collected in all the six sites. -

Cahiers Du BUCREP Volume 01, Numéro 01

Cahiers du BUCREP Volume 01, Numéro 01 Analyses préliminaires des données communautaires dans la Province du sud Cameroun en 2003 Tome 1 Analyses Bureau Central des Recensements Juin 2008 et des Etudes de Population - BUCREP 1 Cahiers du BUCREPvolume 01,numéro 01 DIRECTEUR DE PUBLICATION Madame Bernadette MBARGA, Directeur Général CONSEILLE EDITORIAL Monsieur ABDOULAYE OUMAROU DALIL, Directeur Général Adjoint Monsieur Raphaël MFOULOU, Conseiller Technique Principal - UNFPA / 3ème RGPH COORDONNATEUR TECHNIQUE YOUANA Jean PUBLICATION MBARGA MIMBOE EQUIPE DE REDACTION DE CE TOME Joseph-Blaise DJOUMESSI, Gérard MEVA’A, Ambroise HAKOUA, Pascal MEKONTCHOU, André MIENGUE, Mme Marthe ONANA, Martin TSAFACK, P. Kisito BELINGA, Hervé Joël EFON, Jules Valère MINYA, Lucien FOUNGA COLLABORATION DISTRIBUTION Cellule de la Communication et des Relations Publiques Imprimerie Presses du BUCREP 2 Analyses préliminaires des données communautaires dans la province du SUD CAMEROUN en 2003 SOMMAIRE UNE NOUVELLE SOURCE DE DONNEES 5 METHODOLOGIE DES TRAVAUX CARTOGRAPHIQUES 7 1- PRODUCTIONS DU VILLAGE 8 2- INFRASTRUCTURES SCOLAIRES 12 3- INFRASTRUCTURES SANITAIRES 18 4- INFRASTRUCTURES SOCIOCULTURELLES 23 5- CENTRES D’ETAT CIVIL 25 6- AUTRES INFRASTRUCTURES 29 7- INFRASTRUCTURES TOURISTIQUES 31 8- RESEAU DE DISTRIBUTION D’EAU ET D’ELECTRICITE 36 9- VIE ASSOCIATIVE 39 3 4 Analyses préliminaires des données communautaires dans la province du SUD CAMEROUN en 2003 UNE NOUVELLE SOURCE DE DONNNEES : LE QUESTIONNAIRE LOCALITE Les travaux de cartographie censitaire déjà -

Assessing Cost Efficiency Among Small Scale Rice Producers in the West Region of Cameroon: a Stochastic Frontier Model Approach

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 3, Issue 6, June 2016, PP 1-7 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0306001 www.arcjournals.org Assessing Cost Efficiency among Small Scale Rice Producers in the West Region of Cameroon: A Stochastic Frontier Model Approach Djomo, Raoul Fani*1, Ewung, Bethel1, Egbeadumah, Maryanne Odufa2 1Department of Agricultural Economics. University of Agriculture, Makurdi. Benue-State, Nigeria PMB 2373, Makurdi 2Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Federal University Wukari, PMB 1020 Wukari. Taraba State, Nigeria *[email protected] Abstract: Local farmers’ techniques and knowledge in rice cultivation being deficient and the aid system and research to support such farmers’ activities likewise insufficient, technological progress and increase in rice production are not yet assured. Therefore, this Study was undertaken to assess cost efficiency among small scale rice farmers in the West Region of Cameroon using stochastic frontier model approach. A purposive, multistage and stratified random sampling technique was used in selecting the respondents. A total of 192 small scale rice farmers were purposively selected from four (4) out of eight divisions. Data were collected using structured questionnaires and interview schedule, administered on the respondents were analyzed using descriptive statistics and stochastic frontier cost functions. The result indicates that the coefficient of cost of labour was found positive and significantly influence cost of production in small scale rice production at 1 percent level of probability, implying that increases in cost of labour by one unit will also increase cost of production in small scale rice farming by the value of it coefficient. -

N I G E R I a C H a D Central African Republic Congo

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (September 2020) ! PERSONNES RELEVANT DE Maïné-Soroa !Magaria LA COMPETENCE DU HCR (POCs) Geidam 1,951,731 Gashua ! ! CAR REFUGEES ING CurAi MEROON 306,113 ! LOGONE NIG REFUGEES IN CAMEROON ET CHARI !Hadejia 116,409 Jakusko ! U R B A N R E F U G E E S (CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND 27,173 NIGERIAN REFUGEE LIVING IN URBAN AREA ARE INCLUDED) Kousseri N'Djamena !Kano ASYLUM SEEKERS 9,332 Damaturu Maiduguri Potiskum 1,032,942 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSO! NS (IDPs) * RETURNEES * Waza 484,036 Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees MAYO SAVA Mora ! < 10,000 EXTRÊME-NORD Mokolo DIAMARÉ Biu < 50,000 ! Maroua ! Minawao MAYO Bauchi TSANAGA Yagoua ! Gom! be Mubi ! MAYO KANI !Deba MAYO DANAY < 75000 Kaele MAYO LOUTI !Jos Guider Number! of IDPs N I G E R I A Lafia !Ləre ! < 10,000 ! Yola < 50,000 ! BÉNOUÉ C H A D Jalingo > 75000 ! NORD Moundou Number of returnees ! !Lafia Poli Tchollire < 10,000 ! FARO MAYO REY < 50,000 Wukari ! ! Touboro !Makurdi Beke Chantier > 75000 FARO ET DÉO Tingere ! Beka Paoua Number of asylum seekers Ndip VINA < 10,000 Bocaranga ! ! Borgop Djohong Banyo ADAMAOUA Kounde NORD-OUEST Nkambe Ngam MENCHUM DJEREM Meiganga DONGA MANTUNG MAYO BANYO Tibati Gbatoua Wum BOYO MBÉRÉ Alhamdou !Bozoum Fundong Kumbo BUI CENTRAL Mbengwi MEZAM Ndop MOMO AFRICAN NGO Bamenda KETUNJIA OUEST MANYU Foumban REPUBLBICaoro BAMBOUTOS ! LEBIALEM Gado Mbouda NOUN Yoko Mamfe Dschang MIFI Bandjoun MBAM ET KIM LOM ET DJEREM Baham MENOUA KOUNG KHI KOUPÉ Bafang MANENGOUBA Bangangte Bangem HAUT NKAM Calabar NDÉ SUD-OUEST -

A Collection of 100 Proverbs and Wise Sayings of the Medumba (Cameroon)

A COLLECTION OF 100 PROVERBS AND WISE SAYINGS OF THE MEDUMBA (CAMEROON) BY CIKURU BISHANGI DEVOTHA AFRICAN PROVERBS WORKING GROUP NAIROBI KENYA MAY 2019 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to thank sincerely all those who contributed towards the completion of this document. My greatest thanks go to Fr. Joseph G. Healey for the financial and moral support. My special thanks go to Cephas Agbemenu, Margret Wambere Ireri and Father Joseph Healey. I also thank all the publishers of African Proverbs whose publications gave me good resource and inspiration to do this work. I appreciate the support of the African Proverbs Working Group for reviewing the progress of my work during their meetings. Find in this work all my gratitude. DEDICATION I dedicate this work to God for protecting and strengthening me while working on the Medumba. To HONDI M. Placide, my husband and my mentor who encouraged me to complete this research, To my collaborator Emmanuel Fandja who helped me to collect the 100 Medumba Proverbs. To all the members of my community in Nairobi and to all those who will appreciate in finding out the wisdom that it contains. i A COLLECTION OF 100 MEDUMBA PROVERBS AND WISE SAYINGS (CAMEROOON) INTRODUCTION Location The Bamileke is the native group which is now dominant in Cameroon's West and Northwest Regions. It is part of the Semi-Bantu (or Grassfields Bantu) ethnic group. The Bamileke are regrouped under several groups, each under the guidance of a chief or fon. Nonetheless, all of these groups have the same ancestors and thus share the same history, culture, and languages. -

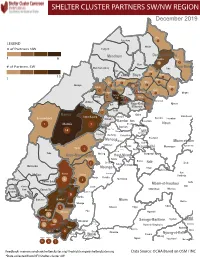

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W.