The Bamendjin Dam and Its Implications in the Upper Noun Valley, Northwest Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

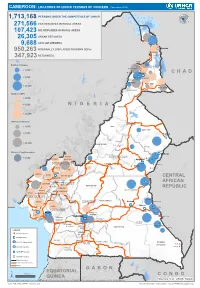

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Mountain Resources Expliotation For

International Journal of Geography and Régional Planning Research Vol.1,No.1,pp.1-12, March 2014 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) MONTANE RESOURCES EXPLOITATION AND THE EMERGENCE OF GENDER ISSUES IN SANTA ECONOMY OF THE WESTERN BAMBOUTOS HIGHLANDS, CAMEROON Zephania Nji FOGWE Department of Geography, Box 3132, F.L.S.S., University of Douala ABSTRACT: Highlands have played key roles in the survival history of humankind. They are refuge heavens of valuable resources like fresh water endemic floral and faunal sanctuaries and other ecological imprints. The mountain resource base in most tropical Africa has been mined rather than managed for the benefit of the low-lying areas. The world over an appreciable population derives its sustenance directly from mountain resources and this makes for about one-tenth of the world’s poorest.The Western highlands of Cameroon are an archetypical territory of a high population density and an economically very active population. The highlands are characterised by an ecological fragility and a multi-faceted socio-economic dynamism at varied levels of poverty, malnutrition and under employment, yet about 80 percent of the Santa highlands’ population depends on its natural resource base of vast fertile land, fresh water and montane refuge forest for their livelihood. KEYWORDS: Montane Resources, Gender Issues, Santa Economy, Western Bamboutos, Cameroon INTRODUCTION The volcanic landscape on the western slopes of the Bamboutos mountain range slopes to the Santa Highlands is an area where agriculture in the form of crop production and animal rearing thrives with remarkable success. Arabica coffee cultivation was in extensive hectares cultivated at altitudes of about 1700m at the Santa Coffee Estate at Mile 12 in the 1970s and 1980s. -

Full Text Article

SJIF Impact Factor: 3.458 WORLD JOURNAL OF ADVANCE ISSN: 2457-0400 Alvine et al. PageVolume: 1 of 3.21 HEALTHCARE RESEARCH Issue: 4. Page N. 07-21 Year: 2019 Original Article www.wjahr.com ASSESSING THE QUALITY OF LIFE IN TOOTHLESS ADULTS IN NDÉ DIVISION (WEST-CAMEROON) Alvine Tchabong1, Anselme Michel Yawat Djogang2,3*, Michael Ashu Agbor1, Serge Honoré Tchoukoua1,2,3, Jean-Paul Sekele Isouradi-Bourley4 and Hubert Ntumba Mulumba4 1School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon. 2School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon. 3Laboratory of Microbiology, Université des Montagnes Teaching Hospital; Bangangté, Cameroon. 4Service of Prosthodontics and Orthodontics, Department of Dental Medicine, University of Kinshasa, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Received date: 29 April 2019 Revised date: 19 May 2019 Accepted date: 09 June 2019 *Corresponding author: Anselme Michel Yawat Djogang School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon ABSTRACT Oral health is essential for the general condition and quality of life. Loss of oral function may be due to tooth loss, which can affect the quality of life of an individual. The aim of our study was to evaluate the quality of life in toothless adults in Ndé division. A total of 1054 edentulous subjects (partial, mixed, total) completed the OHIP-14 questionnaire, used for assessing the quality of life in edentulous patients. Males (63%), were more dominant and the ages of the patients ranged between 18 to 120 years old. Caries (71.6%), were the leading cause of tooth loss followed by poor oral hygiene (63.15%) and the consequence being the loss of aesthetics at 56.6%. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

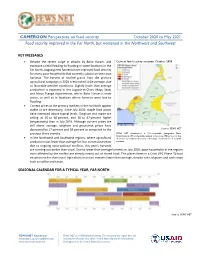

CAMEROON Perspectives on Food Security October 2020 to May 2021 Food Security Improved in the Far North, but Worsened in the Northwest and Southwest

CAMEROON Perspectives on food security October 2020 to May 2021 Food security improved in the Far North, but worsened in the Northwest and Southwest KEY MESSAGES • Despite the recent surge in attacks by Boko Haram, and Current food security situation, October 2020 excessive rainfall leading to flooding in some locations in the Far North, ongoing new harvests have improved food security for many poor households that currently subsist on their own harvests. The harvest of rainfed grains from the primary agricultural campaign in 2020 is estimated to be average, due to favorable weather conditions. Slightly lower than average production is expected in the Logone-et-Chari, Mayo Sava, and Mayo Tsanga departments, where Boko Haram is most active, as well as in locations where harvests were lost to flooding. • Current prices at the primary markets in the Far North appear stable or are decreasing. Since July 2020, staple food prices have increased above typical levels. Sorghum and maize are selling at 46 to 60 percent, and 30 to 47 percent higher (respectively) than in July 2019. Although current prices are still above average, sorghum and groundnut prices have decreased by 17 percent and 18 percent as compared to the Source: FEWS NET previous three months. FEWS NET classification is IPC-compatible (Integrated Phase Classification). IPC-compatible analysis follows key IPC protocols but • In the Northwest and Southwest regions, where agricultural does not necessarily reflect the consensus of national food security production was lower than average for four consecutive years partners. due to ongoing socio-political conflicts, this year's harvests are running out earlier than usual. -

Ancestral Art of Gabon from the Collections of the Barbier-Mueller

ancestral art ofgabon previously published Masques d'Afrique Art ofthe Salomon Islands future publications Art ofNew Guinea Art ofthe Ivory Coast Black Gold louis perrois ancestral art ofgabon from the collections ofthe barbier-mueiler museum photographs pierre-alain ferrazzini translation francine farr dallas museum ofart january 26 - june 15, 1986 los angeles county museum ofart august 28, 1986 - march 22, 1987 ISBN 2-88104-012-8 (ISBN 2-88104-011-X French Edition) contents Directors' Foreword ........................................................ 5 Preface. ................................................................. 7 Maps ,.. .. .. .. .. ...... .. .. .. .. .. 14 Introduction. ............................................................. 19 Chapter I: Eastern Gabon 35 Plates. ........................................................ 59 Chapter II: Southern and Central Gabon ....................................... 85 Plates 105 Chapter III: Northern Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and Southem Cameroon ......... 133 Plates 155 Iliustrated Catalogue ofthe Collection 185 Index ofGeographical Names 227 Index ofPeoplcs 229 Index ofVernacular Names 231 Appendix 235 Bibliography 237 Directors' Foreword The extraordinarily diverse sculptural arts ofthe Dallas, under the auspices of the Smithsonian West African nation ofGabon vary in style from Institution). two-dimcnsional, highly stylized works to three dimensional, relatively naturalistic ones. AU, We are pleased to be able to present this exhibi however, reveal an intense connection with -

Evaluating the Constraints and Opportunities of Maize Production in the West Region of Cameroon for Sustainable Development

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 13, No.4, 2011) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania EVALUATING THE CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES OF MAIZE PRODUCTION IN THE WEST REGION OF CAMEROON FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Godwin Anjeinu Abu1, Raoul Fani Djomo-Choumbou1 and Stephen Adogwu Okpachu2 1. Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Agriculture PMB 2373, Makurdi Benue State- Nigeria 2. Federal College of Education (Technical), Potiskum, Yobe State, Nigeria ABSTRACT A study of Evaluating the constraints and opportunities of Maize production in the West Region of Cameroon was carried out using primary and secondary data collected. One hundred and twenty (120) maize farmers randomly selected from eight (8) villages were interviewed using structured questionnaire. Data from the study were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as frequency distribution, percentages, and inferential statistics such as multiple linear regressions. The study found that most maize farmers in the study area were small scale farmers and are full time farmers, the major maize production constraints was poor access to credit facilities. it was also found any unit increase in the quantity of any of the resources used for maize production will increase maize output by the value of their estimated coefficients respectively , however to raise maize production, the study recommend that financial institutions such as agricultural and community banks should be established in the study area with the simple procedure of securing loans. The relevant government agencies and non- governmental organization should mobilize the maize farmers to form themselves into formidable group so that they can derive maximum benefit of collective union. -

2.3M 1.4M 679K 204K 58.1K

CAMEROON: North-West and South-West Situation Report No. 19 As of 31 May 2020 This report is produced by OCHA Cameroon in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers 1 – 31 May 2020. The next report will be issued in July 2020. MAY 2020 HIGHLIGHTS • An estimated 83,557 pupils and students are eligible to sit for end of cycle exams in 2020. • 16 out of the 37 health districts in the North-West and South-West (NWSW) have confirmed cases of COVID-19. • A cholera outbreak is reported in Tiko and Limbe health districts in the South West. • UNICEF supported the establishment of ten in-patient facilities in NWSW for the management of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) cases with complications. • UNHCR and partner have acquired land to build temporal IDP shelter in some locations in the SW. • OCHA and UNICEF supported a joint cluster led training of 81 front- line NGO staff on transmission, signs, symptoms and prevention of COVID-19 in the NW Region. Source: OCHA • IRC constructed 5 boreholes, rehabilitated 20 water distribution The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on systems and constructed 18 tank bases and tap stands, resulting in this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the an 82.4% increase in water supply coverage compared to April. United Nations. 2.3M 1.4M 679K 204K 58.1K affected people targeted for internally displaced (IDP) Returnees (former Cameroonian assistance IDP) Refugees and Asylum seekers in Nigeria Sources: Sources: Sources: Sources: Sources: Humanitarian Need Humanitarian MSNA in -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Département Bamoun 42 P

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE REfIlUBLIQUE FEDERALE SCIENTIFIQUE ET 'rECHNIQUE DU OUTRE-MER CAMEROUN CENTRE OR5TOM DE YAOUNDE 1 DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES . DU DEPARTEMENT BAMOUN ~prèS la documentation réunie ~ ~ction de Géographiy de l'ORS~ REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN FASCICULE n° 16 SH. n° 44 YAOUNDE Janvier 1968 REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN Fesc. Tabl.eau de là population du Cameroun, 68 p. Fév. 1965 SH. N° 17 Fasc. 2 Dictionnaire des villages du Dia et Lobo, 89 p. Juin 1965 SH. N° 22 Fasc. 3 Dictionnaire des ~illages de la Haute-Sanaga, 53 p. Août 1965 SH. N° 23 Fasc. 4 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Mfoumou, ~~ p. Octobre 1965 SH. N° ?4 Fasc. 5 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Soo 45 p. Novembre 1965 SH. N° 25 Fasc. 6 Dictionnaire des villages du l'-Jtem 126 p. Décembre 1965 SH. N° 26 Fasc. 7 Dictionnaire des villages de la Mefou 108 p. Janvier 1966 SH. N" 27 Fasc. 8 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Kellé 51 p. Février 1966 5H. N° 28 Fasc. 9 Dictionnaire des villages de la Lékié 71 p. Mars 1966 SH. N° 29 Fasc. 10 Dictionnaire des villages de Kribi P. Mars 1966 SH. N° 30 Fasc. 11 Dictionnaire des villages du Mbam 60 P. Mai 1966 SH. N° 31 Fasc. 12 Dictionnaire des villages de Boumba Ngoko 34 p. Juin 1966 SH 39 Fasc. 13 Dictionnaire des villages de Lom-et-Djérem 35 p. Juillet 1967 SH. 40 Fasc. 14 Dictionnaire des villages de la Kadei 52 p. Août 1967 SH. 41 Fasc. -

Assessment of Prunus Africana Bark Exploitation Methods and Sustainable Exploitation in the South West, North-West and Adamaoua Regions of Cameroon

GCP/RAF/408/EC « MOBILISATION ET RENFORCEMENT DES CAPACITES DES PETITES ET MOYENNES ENTREPRISES IMPLIQUEES DANS LES FILIERES DES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE » Assessment of Prunus africana bark exploitation methods and sustainable exploitation in the South west, North-West and Adamaoua regions of Cameroon CIFOR Philip Fonju Nkeng, Verina Ingram, Abdon Awono February 2010 Avec l‟appui financier de la Commission Européenne Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... i ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... ii Abstract .................................................................................................................. iii 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Problem statement ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Research questions .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Importance of the study ................................................................................... 3 2: Literature Review ................................................................................................. -

Cholera Outbreak

Emergency appeal final report Cameroon: Cholera outbreak Emergency appeal n° MDRCM011 GLIDE n° EP-2011-000034-CMR 31 October 2012 Period covered by this Final Report: 04 April 2011 to 30 June 2012 Appeal target (current): CHF 1,361,331. Appeal coverage: 21%; <click here to go directly to the final financial report, or here to view the contact details> Appeal history: This Emergency Appeal was initially launched on 04 April 2011 for CHF 1,249,847 for 12 months to assist 87,500 beneficiaries. CHF 150,000 was initially allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the national society in responding by delivering assistance. Operations update No 1 was issued on 30 May 2011 to revise the objectives and budget of the operation. Operations update No 2 was issued on 31st May 2011 to provide financial statement against revised budget. Operations update No 3 was issued on 12 October 2011 to summarize the achievements 6 months into the operation. Operations update No 4 was issued on 29 February 2012 to extend the timeframe of the operation from 31st March to 30 June 2012 to cover the funding agreement with the American Embassy in Cameroon. PBR No M1111087 was submitted as final report of this operation to the American Embassy in Cameroon on 03 August 2012. Throughout the operation, Cameroon Red Cross volunteers sensitized the populations on PBR No M1111127 was submitted as final report of this how to avoid cholera. Photo/IFRC operation to the British Red Cross on 14 August 2012. Summary: A serious cholera epidemic affected Cameroon since 2010. -

In Lower Sanaga Basin, Cameroon: an Ethnobiological Assessment

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol.6 (4):521-538, 2013 Research Article Conservation status of manatee (Trichechus senegalensis Link 1795) in Lower Sanaga Basin, Cameroon: An ethnobiological assessment. Theodore B. Mayaka1*, Hendriatha C. Awah1 and Gordon Ajonina2 1 Department of Animal Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Dschang, PO Box 67Dschang, Cameroon. Email: *[email protected], [email protected] 2Cameroon Wildlife Conservation Society (CWCS), Coastal Forests and Mangrove Programme Douala-Edea Project, BP 54, Mouanko, Littoral, Cameroon. Email:[email protected] * Corresponding author Abstract An ethnobiological survey of 174 local resource users was conducted in the Lower Sanaga Basin to assess the current conservation status of West African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis, Link 1795) within lakes, rivers, and coast (including mangroves, estuaries and lagoons). Using a multistage sampling design with semi-structured interviews, the study asked three main questions: (i) are manatees still present in Lower Sanaga Basin? (ii) If present, how are their numbers evolving with time? (iii) What are the main threats facing the manatee? Each of these questions led to the formulation and formal testing of a scientific hypothesis. The study outcome is as follows: (i)60% of respondents sighted manatees at least once a month, regardless of habitat type (rivers, lakes, or coast) and seasons (dry, rainy, or both); (ii) depending on habitat type, 69 to 100% of respondents perceived the trend in manatee numbers as either constant or increasing; the increasing trend was ascribed to low kill incidence (due either to increased awareness or lack of adequate equipment) and to high reproduction rate; and (iii) catches (directed or incidental) and habitat degradation (pollution) ranked in decreasing order as perceived threats to manatees.