Marketing Function and Form: How Functionalist and Experiential

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Teaching Innovation on Retail Environmental Design for Consumers with Disabilities

A Teaching Innovation on Retail Environmental Design for Consumers with Disabilities Meng-Hsien (Jenny) Lin, William J. Jones, and Akshaya Vijayalakshmi Purpose of Study: A teaching innovation that bridges the gap identified in current retailing textbooks, which pay minimal attention to serving consumers with disabilities in the marketplace, is proposed and assessed. This retail class project considers not only the legal and profit benefits for the firm, but also the inclusion and sense of normalcy for a consumer from a societal marketing perspective. Method/Design and Sample: Forty-one students working on the retail project were invited to participate in a pre- and post- test survey that investigates 1) their knowledge of disability regulations and accommodations required of retail outlets and 2) the usefulness of the project in advancing their careers and academic learning. In addition to the use of a “cognitive walkthrough” method of data collection for the class project, students were introduced to the concepts and model of servicescape and consumer normalcy in preparation for the project. Results: Results indicated that learning objectives were met and student expectations were achieved through the implementation of the retail project. Value to Marketing Educators: The implications of considering consumers with disabilities in retail environmental design includes: the physical needs of adapting to consumers with disabilities and the psychological need of consumers wanting to be included and perceived as “normal.” The innovation extends students’ learning about consumers with disabilities while reinforcing traditional retail concepts, such as store layout, visual merchandising, consumer behavior, and the notion of a servicescape. The project is adaptable to various marketing courses. -

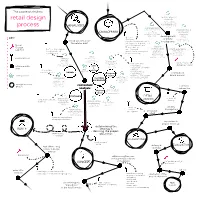

Retail Design Process

The course of a holistic spatial / physical retail design elements lay-out / routing sight-lines / focus points product placement / VM process ANALYSIS interior & exterior shell communication furniture in-store communication organisational & logo DEVELOPMENT corporate identity operational external communication elements digital content development service KEY: - sketches personel - 2D & plans of all the distribution/logistics critical assessment of - capacity / product placement touchpoints check-out process the retailer brief - wireframes (web, mobile, etc.) Retail - levels of communication digital & Design - 3D & renderings Lab tool - Kapferer - brand prism - material board technological brand experience - brand moodboard elements design language - models / rapid prototyping storytelling - brand pyramid website / webshop - virtual technology payment system functional components data-technology sensory elements offer communication methods practical tool identity products & services personality characteristics brand values VM & presentation “status quo” direct competitors tone of voice - trendwatchers - sense matrix image / visual identity start-ups - design guidelines intermediate history offer retail-, and - retail safari step & consumer trends - magazines / academic - Osterwalder staff service literature operational - benchmarking bussiness model BRAND needs unexpected - SWOT-analysis conceptbook component factor - Porter (5 forces model) brand manual next step...? - positioning diagram organisation IN-STORE how to create staff difference, -

Retail Design Guidelines V5

DRAFT Design and Development Controls - Interiors Part 3 V5 It’s part Retail Design Guidelines of our Monash Masterplan Buildings and Property Division I January 2018 Contents The Design and Development Part 1 - Overview Controls - Interiors is a Part 2 - Signage Palette document that is divided into Part 3 - Retail Design Guidelines standalone sections that at Part 4 - Retail Signage Guidelines each project stage - feasibility, briefing, procurement, construction, ongoing and operation and management - consulting designers can be referred to connect with Monash’s overarching ambitions and principles that promote and advise on good design. The four sections enable users to access the information contained in the document to suit their requirements. Smaller and/or less complex projects may only require information contained within the overview, and minimal sections, whilst larger and/or more complex projects may require referencing to the document in its entirety. It’s part Authors of our Monash Campus Design, Quality and Planing, Masterplan Buildings and Property Division, Monash University It’s part of our Monash Masterplan Design and Development Controls - Interiors | Overview Page 2 Preface Interior spaces are the fabric of Monash Sitting within the Buildings and University campus experiences. They Property Division of Monash provide environments for teaching, University the Campus Design, learning and engagement; and influence Quality and Planning(CDQP) team provides strategic people’s experiences of it’s campuses. guidance and advice to designers to affect the To ensure spatial “outcomes will be architecture and design of distinguished yet welcoming, internal and exterior spaces on Monash University campuses contemporary yet enduring, flexible yet in Australia. -

At APPLY.UNCG.EDU INTERIOR ARCHITECTURE

INTERIOR ARCHITECTURE Interior Architecture combines the fundamental interest in human- environmental relationships of interior design with study of interior products, building forms, and systems. The program uses the studio as a physical and intellectual place where students transform ideas into physical and virtual forms, objects, and spaces. Supplied with appropriate aas.uncg.edu facilities, tools, and equipment, students build what they design. Degree Outcomes Major • Employment with design firms specializing in interior design, Interior Architecture (BFA) architecture and related fields such as graphics, furniture, preservation, home furnishings, museums and exhibition, lighting, and more. • Graduate study at prominent national and international institutions. The Student Experience • A holistic, studio-based curriculum with individual workspace for students in a premier facility using state-of-the-art physical and digital technology. • Collaboration with various populations and user groups. Professional Contact experience and service to the community. Stoel Burrowes • Opportunities to study abroad at various locations and visit design Director of Undergraduate Studies centers around the country. [email protected] • Participate in the department’s Center for Community-Engaged Design, the N.C. Main Street program, student chapters of ASID and IIDA and other organizations and partners. • Development of professional skills through a required internship. Accolades & Accomplishments • Students earned first place in recent competitions including the Bernice Bienenstock Library Interior Design Competition; IIDA Carolinas Chapter Student Award; IIDA Student Design Charrette; Retail Design Institute International Student Design Competition; International VELUX Award Department of for Students of Architecture in the Americas; and Sherwin-Williams Interior Architecture Student Design Competition. iarc.uncg.edu • Assistant Professor Amanda Gale named among the 25 Most Admired 336.334.5320 Educators for 2017-18 by DesignIntelligence. -

Rollout Qualifications

Rollout Qualifications 2021 CONTENTS FIRM PROFILE CLIENT LIST RELEVANT EXPERIENCE TEAM Architecture FIRM PROFILE Planning Who We Are Interiors RDC is an award winning architectural firm, with over 40 years of experience. We are a full-service architecture practice, with experience in conceptual design, entitlement, site planning, and all stages of construction documentation and construction administration. Sustainability Our depth and excellence in architecture allows us to take a comprehensive approach when designing spaces. Our history of successful design, client relationships and exquisite architecture proves us as forerunners in our field, leading the industry in designing retail, mixed use, hospitality, and Development entertainment venues. Services RDC’s collaborative practice of architecture, planning and interior design creatively meets the diverse needs of a variety of projects. We work to develop creative solutions that are both functional and cost effective while Store Nationwide Offices taking into consideration the goals of the client, surrounding communities Planning and emerging online ordering, pick-up and delivery trends. Our practice encompasses many different scales, from small store planning, prototype design and rollout, to large master plans and everything in between. 6 Procurement Geographic Reach and National Bandwidth RDC’s 180-member professional team works across a flexible structure that Retail can expand and contract according to our clients’ workloads and needs. All 5 of our offices are aligned with the same -

The Strategic Evolution of Fashion Flagship Stores

International Journal of Business and Management; Vol. 14, No. 9; 2019 ISSN 1833-3850 E-ISSN 1833-8119 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Strategic Evolution of Fashion Flagship Stores Edoardo Sabbadin1 & Simone Aiolfi2 1 Professor of Marketing, Department of Economics, University of Parma, Italy 2 Adjunct Professor of Marketing, Department of Economics, University of Parma, Italy Correspondence: Prof. Simone Aiolfi, Department of Economics, University of Parma, Via J.F. Kennedy 6 – Parma - 43125, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 14, 2019 Accepted: June 20, 2019 Online Published: August 5, 2019 doi:10.5539/ijbm.v14n9p123 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v14n9p123 Abstract About thirty-five years ago the trend of investing in flagship stores in the fashion and luxury sectors started, and has not stopped even since the last economic crisis. Recently, flagship stores have expanded into new sectors. There is an increased interest in flagship stores; but until now, they have received little attention in academic research. Published papers are mainly related to the fields of luxury shopping and internationalization studies. Nowadays, the term “flagship store” is ambiguous; it has different meanings. A flagship brand store is, in general terms, the most important, expensive, and representative store of the brand. It has to show the full range of products and services offered. Usually it is the largest store, in the most prestigious location, and adopts original store design solutions; they offer new facilities, and a very high service level. Moreover, flagship designers are famous and prestigious architects; (“Signature” architects, or “Archistars”) and the aim is to create iconic buildings. -

Retail Design Rules & Guidelines

Retail Design Rules & Guidelines choosebrock.ca bacd.ca forsefield.com BETTER YOUR BUSINESS | Retail Design Rules & Guidelines Table of Contents 7. Good Visibility .......................................................... 5 Introduction ........................................................................ 1 8. Checkout ................................................................... 5 Retail Design & Foot Traffic Optimization ................. 1 Design in the Retail Space .............................................. 6 1. First Impressions ..................................................... 2 Brand Considerations ...................................................... 6 2. The Transition Zone ................................................ 2 Interior Design Elements ................................................ 6 3. Choose a Suitable Layout ...................................... 3 Accent Walls .................................................................. 7 4. Minimize Counters .................................................. 3 Create Windows ........................................................... 7 5. Beware the Butt-Brush! .......................................... 4 Think Vertical ................................................................ 7 6. Slow Them Down .................................................... 4 Lighting ......................................................................... 7 Introduction The ideas behind “Three Foot Marketing” provide a helpful introduction to the importance of store -

Slow Fashion + Retail Design: Designing Experiences to Influence Sustainable Consumers Behaviors

Slow Fashion + Retail Design: Designing experiences to influence sustainable consumers behaviors Rebekah L. Matheny The Ohio State University, USA [email protected] Abstract Driven by increased demands for ethical responsibility towards environmental and social sustainability by Millennials and GenZ, the design and purpose of apparel retail stores is transforming. These generations demand authentic and transparent retail storytelling to create a connection between their beliefs and the value they place on the products they purchase. Kate Fletcher, who introduced the concept of slow fashion, states: “Sustainable fashion is about a strong and nurturing relationship between consumer and producer” (Fletcher, 2008/2014). The retail store environment is a critical link in establishing this relationship. However, many slow fashion retailers lack elements within their store design to foster this relationship, missing an opportunity to communicate their sustainable story through the physical space where consumers experience fashion. Therefore, we must broaden slow fashion’s reach, extending into the design of the physical retail environment, and establishing slow retail experiences. Utilizing Fletcher and Grose’s principles of transforming slow fashion, this paper presents four slow fashion retail case studies, examining the spatial elements necessary to foster stronger relationships between consumer and producer. The case studies examine how retail store designs successfully apply design elements through physical, human, and digital touchpoints to use the store as an educator on sustainable apparel practices. Serving as guiding examples, these case studies illustrate how other sustainable fashion retailers can leverage storytelling elements within their own retail environments. Retailers and designers can use the examples presented to better connect, communicate, and educate their customers on their brand's core sustainable values to encourage changing behaviors. -

2021 Marketing Planner OUR MISSION

2021 Marketing Planner www.vmsd.com OUR MISSION Visual Merchandising Store Design (VMSD) provides retail professionals with the most up-to-date, innovative retail design ideas and industry news— and does so in a way that inspires, challenges and motivates. VMSD celebrates the art and science of retail design, drawing on more than 120 years of history serving this market, delivering information and inspiration straight from the high-level executives who drive this industry. VMSD Magazine has Been Proudly Serving the Retail Design Industry Since 1897 PREMIERE COVERAGE From the Editor-in-Chief/Associate Publisher At VMSD, we’re committed to delivering the most compelling, relevant and innovative retail design trends, strategies and case studies to our targeted audience of retail professionals worldwide. These high-level executives are hungry for focused editorial content to guide them as they create and rethink innovative retail environments of every size and format. VMSD magazine has served this industry for more than 120 years, delivering exclusive content that inspires, challenges and motivates. We’ve seen the industry through good times and bad. But you won’t find us complacent in our legacy of leadership. We continuously review and refresh our offerings across each of our print, digital and events brand platforms. Exclusive features give the reader an inside look at the latest, most innovative new concepts and renovations in the market. We also regularly feature in-depth reports on emerging trends and sector spotlights. VMSD Showroom is our beautifully designed products section, which features the best new products targeting all categories of retail. Be sure to check out VMSD.com, where you’ll find daily industry news, eye- catching new products, thought-provoking blogs and cutting-edge design projects accompanied by visually stunning images in an easy-to browse gallery format. -

Lifestyles As Destination: Retail Design Today

NEW YORK CITY Home About FGI Membership Lounge Events Trends Professional Careers Student Center Archives Partners Lifestyles as Destination: Retail Design Today Given the increasing competition of today’s fashion market, the luxury fashion store has become as important an identity statement for the fashion designer as the collection itself. by Kenne Shepherd Leading fashion houses today are racing to create spectacular new stores that offer their customers a 'total lifestyle' experience. Stores that not only showcase the designers' collection, but are an architec- tural expression of that collection. Given the increasing competition of today's fashion market, the luxury fashion store has become as important an identity statement for the fashion designer as the collection itself. It is an extension of a unified worldwide fashion image, in a world where image is the lifeblood of the industry. Today's new retail environments are the most powerful display of identity that the fashion retailer has at its disposal. Through the experience it offers its customer, the fashion store breathes life into the design- er's work and the lifestyle it defines. It is the retail environment that provides a three-dimensional back- drop and enclosure for the merchandise while creating opportunities for exciting visuals and dramatic vistas that draw the customer through the store arousing curiosity, interest and excitement with the ultimate goal that the customer "buys in" to the designer's lifestyle. Fashion is about change, yet staying true to the brand image. The genius of designers like Calvin Klein, Prada, and Gucci is their ability to remain true to their vision while interpreting it in new and modern ways that define not just today's lifestyle, but tomor- row's lifestyle as well. -

How the Construction Brick Became the Rockstar in Retail Design

IT'S TRENDING: HOW THE CONSTRUCTION BRICK BECAME THE ROCKSTAR IN RETAIL DESIGN Anything terra-coa has been This report observes how bricks used, redefined, modernized, are being used in the Retail and given a new life in the field. recent two years. Designer Room on Fire Tigerlily Sydney Brand Flagship Store Photography Sean Fennessy 1 Design office Room On Fire The perforaon of a secon of took inspiraon from Sydney’s the brick façade allows light to coastal landscape and beaches pass through and adds an for Tigerlily’s store. The outer enchanng glow to the façade is made of Bowral architectural element. The same bricks, a locally manufactured mof is then repeated inside building block characterized by the store, creang a subtle a pale sandstone color. dialogue between inside and outside. Designer Room on Fire Tigerlily Sydney Brand Flagship Store Sean Fennessy (incl. Photography following image) 2 The modular and effortless The building blocks were hand- element of the brick creates an made from Oaxacan red earth incredibly intricate at the by Patricia Medivil, whose Aesop store in Brooklyn by specialty is this specific rosy Mexican architect Frida hue. Escobedo. Designer Frida Escobedo Brand Aesop Park Slope Photography Courtesy of Aesop 4 In the Coffee Nap Roasters 2nd customers could live a new in Seoul by Design Studio experience. There is no fixed MAOOM, bricks are the chosen sing spot. Depending on your material to create an evocave state of mind, the type of sight space where to sit and relax for you want to enjoy, you can a moment. -

Visual Merchandising and Display, Chapter 1

PRINTED BY: chris selleck <[email protected]>. Printing is for personal, private use only. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted without publisher's prior permission. Violators will be prosecuted. 1 1 Chapter One Why Do We Display? 1.1 AFTER YOU HAVE READ THIS CHAPTER, YOU WILL BE ABLE TO DISCUSS ♦ the definition of visual merchandising ♦ the concept of store image and its relationship to visual merchandising and display ♦ the purposes of visual merchandising 1 We show in order to sell. Display or visual merchandising is showing merchandise and concepts at their very best, with the 2 end purpose of making a sale. We may not actually sell the object displayed or the idea promoted, but we do attempt to convince the viewer of the value of the object, the store promoting the object, or the organization behind the concept. Although a cash register may not ring because of a particular display, that display should make an impression on the viewer that will affect future sales. The display person used to be the purveyor of dreams and fantasies, presenting merchandise in settings that stirred the imagination and promoted fantastic flights to unattainable heights. Today's display person, however, sells a “reality.” Today's shopper can be whatever he or she wants to be by simply wearing garments with certain labels that have a built-in status. The display person dresses a mannequin (possessing a perfect figure) in skin-tight jeans, flashes the lights, adds the adoring males or females, and reinforces the image of sexuality and devastating attractiveness that is part of the prominent name on the label.