Design Factors in the Museum Visitor Experience Regan Forrest Bsc (Hons) Grad Dip Sci Comm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Teaching Innovation on Retail Environmental Design for Consumers with Disabilities

A Teaching Innovation on Retail Environmental Design for Consumers with Disabilities Meng-Hsien (Jenny) Lin, William J. Jones, and Akshaya Vijayalakshmi Purpose of Study: A teaching innovation that bridges the gap identified in current retailing textbooks, which pay minimal attention to serving consumers with disabilities in the marketplace, is proposed and assessed. This retail class project considers not only the legal and profit benefits for the firm, but also the inclusion and sense of normalcy for a consumer from a societal marketing perspective. Method/Design and Sample: Forty-one students working on the retail project were invited to participate in a pre- and post- test survey that investigates 1) their knowledge of disability regulations and accommodations required of retail outlets and 2) the usefulness of the project in advancing their careers and academic learning. In addition to the use of a “cognitive walkthrough” method of data collection for the class project, students were introduced to the concepts and model of servicescape and consumer normalcy in preparation for the project. Results: Results indicated that learning objectives were met and student expectations were achieved through the implementation of the retail project. Value to Marketing Educators: The implications of considering consumers with disabilities in retail environmental design includes: the physical needs of adapting to consumers with disabilities and the psychological need of consumers wanting to be included and perceived as “normal.” The innovation extends students’ learning about consumers with disabilities while reinforcing traditional retail concepts, such as store layout, visual merchandising, consumer behavior, and the notion of a servicescape. The project is adaptable to various marketing courses. -

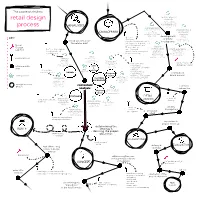

Retail Design Process

The course of a holistic spatial / physical retail design elements lay-out / routing sight-lines / focus points product placement / VM process ANALYSIS interior & exterior shell communication furniture in-store communication organisational & logo DEVELOPMENT corporate identity operational external communication elements digital content development service KEY: - sketches personel - 2D & plans of all the distribution/logistics critical assessment of - capacity / product placement touchpoints check-out process the retailer brief - wireframes (web, mobile, etc.) Retail - levels of communication digital & Design - 3D & renderings Lab tool - Kapferer - brand prism - material board technological brand experience - brand moodboard elements design language - models / rapid prototyping storytelling - brand pyramid website / webshop - virtual technology payment system functional components data-technology sensory elements offer communication methods practical tool identity products & services personality characteristics brand values VM & presentation “status quo” direct competitors tone of voice - trendwatchers - sense matrix image / visual identity start-ups - design guidelines intermediate history offer retail-, and - retail safari step & consumer trends - magazines / academic - Osterwalder staff service literature operational - benchmarking bussiness model BRAND needs unexpected - SWOT-analysis conceptbook component factor - Porter (5 forces model) brand manual next step...? - positioning diagram organisation IN-STORE how to create staff difference, -

The 227-Mile Museum, Or, Why We Need a Visitors' Bill of Rights

The 227-Mile Museum, or, Why We Need a Visitors' Bill of Rights Judy Rand Rand and Associates I'd like to begin by saying "Thank you." Oh, I know, that's backwards. You're supposed to say "thank you" at the end of a speech. At the beginning, you say "I'm happy to be here." But you do deserve thanks, and you should take some credit. You've spent your lives, most of you, listening to visitors. Listening outside the museum walls to learn what visitors really do in our exhibits. And because you do, and you share what you learn, our exhibits have been getting better and better. Ever since I discovered you, and what you do, I've been getting better. I' m not an evaluator myself, but I use evaluation as much as I can. As an exhibit developer, it's my job to imagine the exhibit. "What will visitors do, see, hear, experience in this exhibit? What could they learn? What could they feel? What will they take home with them?" I work with museums to uncover the stories they have to tell, the things they want to show. I find the big idea, a storyline, a clever approach to hold it all together. And then, using what I know about media, and what I know about visitors, I weave it into a rich, relevant visitor experience, ready to draw up and build. With lots of help, of course. And you've helped me more than you know. Visitor studies gave me a place to start. -

An Attention-Value Model of Museum Visitors

Visitor Attention 1 AN ATTENTION-VALUE MODEL OF MUSEUM VISITORS Stephen Bitgood Professor Emeritus of Psychology Jacksonville State University INTRODUCTION In their recently published textbook on cognitive psychology, Ashcraft and Radvansky (2010) described attention as “one of cognitive psychology’s most important topics and one of our oldest puzzles.” Whether we examine human attention in the context of driving an automobile, completing a workplace task, or engaging in educational and recreational activities, the importance of attention processes should not be understated. Talking on a cellular phone or texting while driving an automobile can have a disastrous impact on safe driving. Workplace accidents and errors are often attributed to a lack of focused attention on the task. Failing to pay attention to a lecturer in a school classroom may result in a failing grade. And, in museums, distractions that prevent attending to relevant materials leave the visitor unsatisfied and the goals of the museum unfulfilled. With a few exceptions, the topic of visitor attention has rarely been examined in a comprehensive manner. Emphasis is often placed upon an inferred outcome of attention such as “learning,” “flow,” “restoration,” or “satisfaction” rather than on the processes that make these outcomes possible. Despite the general lack of concern regarding attention in museums, a number of individuals have contributed to our current knowledge, the most prominent of whom include Edward Robinson, Arthur Melton, Harris Shettel, Chan Screven, John Koran, John Falk, Giana Moscardo, and Jay Rounds. The attention-value approach described here is relevant to all of informal science education, although the current paper focuses primarily on exhibition environments. -

Designs for Learning: Studying Science Museum Exhibits That Do More Than Entertain

Designs for Learning: Studying Science Museum Exhibits That Do More Than Entertain SUE ALLEN Exploratorium, San Francisco, CA 94123, USA Received 2 October 2003; revised 6 April 2004; accepted 7 April 2004 DOI 10.1002/sce.20016 Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). ABSTRACT: Science museum staff face a constructivist dilemma as they design their public spaces: the exhibits should facilitate science learning, yet they also need to support a diverse visiting public in making their own personal choices about where to attend, what to do, and how to interpret their interactions. To be effective as teaching tools, exhibits need to be highly intrinsically motivating at every step of an interaction in order to sustain involvement by an audience who views their visit primarily as a leisure activity. Given these challenges, it is vital to support the design process with a strong program of research and evaluation. I give a personal perspective on one institution’s research and evaluation work over the last decade, focusing on four areas: immediate apprehendability, physical interactivity, conceptual coherence, and diversity of learners. C 2004 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Sci Ed 88(Suppl. 1):S17–S33, 2004 INTRODUCTION: A PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE ON A LEARNING DILEMMA In this article I present a personal perspective on a subset of museum learning environ- ments, specifically the exhibition space of hands-on science museums. This choice is based on my own experience of studying and working in such environments over the last decade at the Exploratorium, a well-known museum of “science, art, and human perception” in San Francisco. -

Az Általános Muzeológia Kézikönyve Metamuzeológia, Történeti Muzeológia, Elméleti Muzeológia

Friedrich Waidacher Az általános muzeológia kézikönyve Metamuzeológia, történeti muzeológia, elméleti muzeológia ELTE BTK Művészettörténeti Intézet, Budapest, 2011. Friedrich Waidacher: Az általános muzeológia kézikönyve. Metamuzeológia, történeti muzeológia, elméleti muzeológia. ELTE BTK Művészettörténeti Intézet, Budapest, 2011. Oktatási segédanyag: A fordítás készült a „TÁMOP-4.1.2-08/2/A/KMR-2009-0052 – Muzeológiai alprojekt” keretében Fordította: Mélyi József Szerkesztette: Szőke Annamária A fordítás Friedrich Waidacher: Handbuch der Allgemeinen Museologie. 3., unferänderte Auflage. Böhlau Verlag, Wien, Köln, Weimar, 1999. alapján készült. A könyvet részleteiben lásd a Google könyvek között: http://books.google.com/books?id=YqZqUlcP6MIC&lr=&hl=hu © Friedrich Waidacher, a fordító, a szerkesztő Tartalomjegyzék 1. METAMUZEOLÓGIA 1 1.1. Alapgondolatok 2 A muzeológia megismerésének tárgya 3 A muzeológia definíciója 7 1.2. Összefüggések 10 A muzeológia rendszere 10 Szakirodalom 16 Kitérő: Tudománytan 19 A tudomány alapelvei 19 Terminológia 20 Definíció és ítélet 22 A muzeológia fogalmai 23 Hipotézis és elmélet 24 A muzeológia megismerési módszerei 26 2. TÖRTÉNETI MUZEOLÓGIA 30 2.1. A muzeáljelenség története 31 A muzeális viszony 31 Múzeumtörténet és muzeáltörténet 32 A muzeáltörténet forrásai 33 Muzeális és megőrző gyűjtés 34 Kutatástörténet 34 Periodizáció 35 A gyűjtemények nyilvánossága 36 2.1.1. PREMUZEÁLIS KORSZAK 38 Legkorábbi megközelítések 38 Görög antikvitás 38 Római antikvitás 39 Európa az antikvitás után 40 Ázsia 40 2.1.2. PROTOMUZEÁLIS KORSZAK 41 Fejedelmek és pápák mint gyűjtők 41 Naturáliagyűjtemények 42 Kunst- und Wunderkammerek 43 A múzeum mint eszme 45 2.1.3. PALEOMUZEÁLIS KORSZAK 45 Polgári gyűjtemények 45 Udvari reprezentáció 47 2.1.4. MEZOMUZEÁLIS KORSZAK 49 Nyilvános múzeumok 49 Új múzeumfajták 50 Térformák 56 Megvilágítás 57 A múzeum mint önálló épülettípus 58 2.1.5. -

Retail Design Guidelines V5

DRAFT Design and Development Controls - Interiors Part 3 V5 It’s part Retail Design Guidelines of our Monash Masterplan Buildings and Property Division I January 2018 Contents The Design and Development Part 1 - Overview Controls - Interiors is a Part 2 - Signage Palette document that is divided into Part 3 - Retail Design Guidelines standalone sections that at Part 4 - Retail Signage Guidelines each project stage - feasibility, briefing, procurement, construction, ongoing and operation and management - consulting designers can be referred to connect with Monash’s overarching ambitions and principles that promote and advise on good design. The four sections enable users to access the information contained in the document to suit their requirements. Smaller and/or less complex projects may only require information contained within the overview, and minimal sections, whilst larger and/or more complex projects may require referencing to the document in its entirety. It’s part Authors of our Monash Campus Design, Quality and Planing, Masterplan Buildings and Property Division, Monash University It’s part of our Monash Masterplan Design and Development Controls - Interiors | Overview Page 2 Preface Interior spaces are the fabric of Monash Sitting within the Buildings and University campus experiences. They Property Division of Monash provide environments for teaching, University the Campus Design, learning and engagement; and influence Quality and Planning(CDQP) team provides strategic people’s experiences of it’s campuses. guidance and advice to designers to affect the To ensure spatial “outcomes will be architecture and design of distinguished yet welcoming, internal and exterior spaces on Monash University campuses contemporary yet enduring, flexible yet in Australia. -

At APPLY.UNCG.EDU INTERIOR ARCHITECTURE

INTERIOR ARCHITECTURE Interior Architecture combines the fundamental interest in human- environmental relationships of interior design with study of interior products, building forms, and systems. The program uses the studio as a physical and intellectual place where students transform ideas into physical and virtual forms, objects, and spaces. Supplied with appropriate aas.uncg.edu facilities, tools, and equipment, students build what they design. Degree Outcomes Major • Employment with design firms specializing in interior design, Interior Architecture (BFA) architecture and related fields such as graphics, furniture, preservation, home furnishings, museums and exhibition, lighting, and more. • Graduate study at prominent national and international institutions. The Student Experience • A holistic, studio-based curriculum with individual workspace for students in a premier facility using state-of-the-art physical and digital technology. • Collaboration with various populations and user groups. Professional Contact experience and service to the community. Stoel Burrowes • Opportunities to study abroad at various locations and visit design Director of Undergraduate Studies centers around the country. [email protected] • Participate in the department’s Center for Community-Engaged Design, the N.C. Main Street program, student chapters of ASID and IIDA and other organizations and partners. • Development of professional skills through a required internship. Accolades & Accomplishments • Students earned first place in recent competitions including the Bernice Bienenstock Library Interior Design Competition; IIDA Carolinas Chapter Student Award; IIDA Student Design Charrette; Retail Design Institute International Student Design Competition; International VELUX Award Department of for Students of Architecture in the Americas; and Sherwin-Williams Interior Architecture Student Design Competition. iarc.uncg.edu • Assistant Professor Amanda Gale named among the 25 Most Admired 336.334.5320 Educators for 2017-18 by DesignIntelligence. -

Rollout Qualifications

Rollout Qualifications 2021 CONTENTS FIRM PROFILE CLIENT LIST RELEVANT EXPERIENCE TEAM Architecture FIRM PROFILE Planning Who We Are Interiors RDC is an award winning architectural firm, with over 40 years of experience. We are a full-service architecture practice, with experience in conceptual design, entitlement, site planning, and all stages of construction documentation and construction administration. Sustainability Our depth and excellence in architecture allows us to take a comprehensive approach when designing spaces. Our history of successful design, client relationships and exquisite architecture proves us as forerunners in our field, leading the industry in designing retail, mixed use, hospitality, and Development entertainment venues. Services RDC’s collaborative practice of architecture, planning and interior design creatively meets the diverse needs of a variety of projects. We work to develop creative solutions that are both functional and cost effective while Store Nationwide Offices taking into consideration the goals of the client, surrounding communities Planning and emerging online ordering, pick-up and delivery trends. Our practice encompasses many different scales, from small store planning, prototype design and rollout, to large master plans and everything in between. 6 Procurement Geographic Reach and National Bandwidth RDC’s 180-member professional team works across a flexible structure that Retail can expand and contract according to our clients’ workloads and needs. All 5 of our offices are aligned with the same -

The Strategic Evolution of Fashion Flagship Stores

International Journal of Business and Management; Vol. 14, No. 9; 2019 ISSN 1833-3850 E-ISSN 1833-8119 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Strategic Evolution of Fashion Flagship Stores Edoardo Sabbadin1 & Simone Aiolfi2 1 Professor of Marketing, Department of Economics, University of Parma, Italy 2 Adjunct Professor of Marketing, Department of Economics, University of Parma, Italy Correspondence: Prof. Simone Aiolfi, Department of Economics, University of Parma, Via J.F. Kennedy 6 – Parma - 43125, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 14, 2019 Accepted: June 20, 2019 Online Published: August 5, 2019 doi:10.5539/ijbm.v14n9p123 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v14n9p123 Abstract About thirty-five years ago the trend of investing in flagship stores in the fashion and luxury sectors started, and has not stopped even since the last economic crisis. Recently, flagship stores have expanded into new sectors. There is an increased interest in flagship stores; but until now, they have received little attention in academic research. Published papers are mainly related to the fields of luxury shopping and internationalization studies. Nowadays, the term “flagship store” is ambiguous; it has different meanings. A flagship brand store is, in general terms, the most important, expensive, and representative store of the brand. It has to show the full range of products and services offered. Usually it is the largest store, in the most prestigious location, and adopts original store design solutions; they offer new facilities, and a very high service level. Moreover, flagship designers are famous and prestigious architects; (“Signature” architects, or “Archistars”) and the aim is to create iconic buildings. -

Retail Design Rules & Guidelines

Retail Design Rules & Guidelines choosebrock.ca bacd.ca forsefield.com BETTER YOUR BUSINESS | Retail Design Rules & Guidelines Table of Contents 7. Good Visibility .......................................................... 5 Introduction ........................................................................ 1 8. Checkout ................................................................... 5 Retail Design & Foot Traffic Optimization ................. 1 Design in the Retail Space .............................................. 6 1. First Impressions ..................................................... 2 Brand Considerations ...................................................... 6 2. The Transition Zone ................................................ 2 Interior Design Elements ................................................ 6 3. Choose a Suitable Layout ...................................... 3 Accent Walls .................................................................. 7 4. Minimize Counters .................................................. 3 Create Windows ........................................................... 7 5. Beware the Butt-Brush! .......................................... 4 Think Vertical ................................................................ 7 6. Slow Them Down .................................................... 4 Lighting ......................................................................... 7 Introduction The ideas behind “Three Foot Marketing” provide a helpful introduction to the importance of store -

Slow Fashion + Retail Design: Designing Experiences to Influence Sustainable Consumers Behaviors

Slow Fashion + Retail Design: Designing experiences to influence sustainable consumers behaviors Rebekah L. Matheny The Ohio State University, USA [email protected] Abstract Driven by increased demands for ethical responsibility towards environmental and social sustainability by Millennials and GenZ, the design and purpose of apparel retail stores is transforming. These generations demand authentic and transparent retail storytelling to create a connection between their beliefs and the value they place on the products they purchase. Kate Fletcher, who introduced the concept of slow fashion, states: “Sustainable fashion is about a strong and nurturing relationship between consumer and producer” (Fletcher, 2008/2014). The retail store environment is a critical link in establishing this relationship. However, many slow fashion retailers lack elements within their store design to foster this relationship, missing an opportunity to communicate their sustainable story through the physical space where consumers experience fashion. Therefore, we must broaden slow fashion’s reach, extending into the design of the physical retail environment, and establishing slow retail experiences. Utilizing Fletcher and Grose’s principles of transforming slow fashion, this paper presents four slow fashion retail case studies, examining the spatial elements necessary to foster stronger relationships between consumer and producer. The case studies examine how retail store designs successfully apply design elements through physical, human, and digital touchpoints to use the store as an educator on sustainable apparel practices. Serving as guiding examples, these case studies illustrate how other sustainable fashion retailers can leverage storytelling elements within their own retail environments. Retailers and designers can use the examples presented to better connect, communicate, and educate their customers on their brand's core sustainable values to encourage changing behaviors.