Inventing Kung Fu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE December 8, 2016 TO: Members, Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade FROM: Committee Majority Staff RE: Hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 2016, at 10:00 a.m. in 2322 Rayburn House Office Building, the Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade will hold a hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” II. WITNESSES The Subcommittee will hear from the following witnesses: Randy Couture, President, Xtreme Couture; Lydia Robertson, Treasurer, Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports; Jeff Novitzky, Vice President, Athlete Health and Performance, Ultimate Fighting Championship; and Dr. Ann McKee, Professor of Neurology & Pathology, Neuropathology Core, Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Boston University III. BACKGROUND A. Introduction Modern mixed martial arts (MMA) can be traced back to Greek fighting events known as pankration (meaning “all powers”), first introduced as part of the Olympic Games in the Seventh Century, B.C.1 However, pankration usually involved few rules, while modern MMA is generally governed by significant rules and regulations.2 As its name denotes, MMA owes its 1 JOSH GROSS, ALI VS.INOKI: THE FORGOTTEN FIGHT THAT INSPIRED MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND LAUNCHED SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT 18-19 (2016). 2 Jad Semaan, Ancient Greek Pankration: The Origins of MMA, Part One, BLEACHERREPORT (Jun. 9, 2009), available at http://bleacherreport.com/articles/28473-ancient-greek-pankration-the-origins-of-mma-part-one. -

The Evolution from Martial Arts to Self Defence

The Evolution from Martial Arts to Self Defence There is no doubt that Jujitsu has changed along with human evolution. Currently, this art has shifted to more functional practices to suit present needs. With this change in Jujitsu practices, it has taken it away from being a martial art and transformed to a self-defence style, combat sport or combat art. The etymology of martial art is of importance in determining whether Jujitsu can still be classified as such. In this context, martial means ‘of war, warlike’ and art a ‘nonscientific branch of knowledge’. Taking this description into account, can it be stated still that Jujitsu is a warlike art? Jujitsu was originally a martial art from Japan created to defeat an opponent without using weapons or only a short weapon. Jujitsu was developed among the samurai of feudal Japan and also, limited to this upper class group. The Samurais knew that striking against an armored opponent was ineffective, hence they learned to neutralize the enemies by using forms of pins, joint locks, and throws. These techniques were developed based on the principle mentioned above that seeks to use the attacker's energy against them. There are many variations of the art, which leads to a diversity of approaches. Jujutsu schools (ryū) may utilize all forms of grappling techniques to some degree, for example, throwing, trapping, joint locks, holds, gouging, biting, disengagements, striking, and kicking. In addition to jujitsu, many schools teach the use of weapons. Then, to describe Jujitsu as a martial art would no longer be correct as it is no longer used to defeat opponents that wear armour or carry small weapons in battle fields. -

Health Benefits & Risks in the Young Judo Athlete

Health Benefits & Risks in the Young Judo Athlete USA Judo Sports Medicine Subcommittee Robert S. Nishime, M.D. The goal of USA Judo Sports Medicine is to promote and facilitate a healthy athletic lifestyle through safe judo participation. The health and safety of judo participants should always remain the number priority when advising or caring for our athletes. History and Philosophy Judo is one of the most participated sports worldwide, with practitioners spanning all age groups, gender lines, and ethnicities. Judo was originally derived from a truly “combat” oriented martial art known as jujitsu. Jujitsu was basically developed in medieval feudal Japan for battlefield ‘hand-to-hand/sword’ confrontations when a Samurai warrior lost his sword during combat. Therefore jujitsu became by necessity, a “dangerous” form of combat for survival and an adjunctive tool for victory during war. However, through the founder of judo, Professor Jigoro Kano, jujitsu made a profound transition from a dangerous, primarily combative art form. Professor Kano modified various styles of jujitsu into a “safe”, life enhancing martial art, which he called Judo or the “gentle way”, that is now an Olympic sport. He accomplished this in part by removing many of the striking, kicking, gouging, and joint locking techniques that were primarily intended to maim or injure an opponent. He retained and created techniques that could be practiced relatively safely and harmoniously between practitioners. He placed much emphasis on achieving “mutual benefit” when individuals train together. Professor Kano redirected the primary goals of training in his martial art from self-defense and survival to the development of mind, body, and character. -

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk White, Luke ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7080-7243 (2017) Toward an aesthetic of weightlessness: Qinggong and Wire-fu. In: RoCH Fans and Legends. lok, susan pui san, ed. QUAD / Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art, Derby / Manchester. ISBN 9780995461109. [Book Section] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/24696/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

State Athletic Commission 10/25/13 523

523 CMR: STATE ATHLETIC COMMISSION Table of Contents Page (523 CMR 1.00 THROUGH 4.00: RESERVED) 7 523 CMR 5.00: GENERAL PROVISIONS 31 Section 5.01: Definitions 31 Section 5.02: Application 32 Section 5.03: Variances 32 523 CMR 6.00: LICENSING AND REGISTRATION 33 Section 6.01: General Licensing Requirements: Application; Conditions and Agreements; False Statements; Proof of Identity; Appearance Before Commission; Fee for Issuance or Renewal; Period of Validity 33 Section 6.02: Physical and Medical Examinations and Tests 34 Section 6.03: Application and Renewal of a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant 35 Section 6.04: Initial Application for a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant New to Massachusetts 35 Section 6.05: Application by an Amateur for a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant 35 Section 6.06: Application for License as a Promoter 36 Section 6.07: Application for License as a Second 36 Section 6.08: Application for License as a Manager or Trainer 36 Section 6.09: Manager or Trainer May Act as Second Without Second’s License 36 Section 6.10: Application for License as a Referee, Judge, Timekeeper, and Ringside Physician 36 Section 6.11: Application for License as a Matchmaker 36 Section 6.12: Applicants, Licensees and Officials Must Submit Material to Commission as Directed 36 Section 6.13: Grounds for Denial of Application for License 37 Section 6.14: Application for New License or Petition for Reinstatement of License after Denial, Revocation or Suspension 37 Section 6.15: Effect of Expiration of License on -

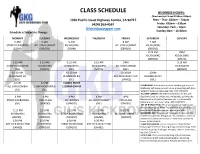

Class Schedule

CLASS SCHEDULE BUSINESS HOURS: (Wednesdays Closed 1130am-330pm) 1930 Pacific Coast Highway Lomita, CA 90717 Mon – Thur: 830am – 730pm (424) 263-4567 Friday: 830am – 630pm Saturday: 7am – 12pm Gilskickboxinggym.com Sunday: 8am – 10:30am Schedule is Subject to Change. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 6 AM 6 AM 6 AM 6 AM 7 AM STRAP KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING (JOHN) (SERGIO) (JOHN) (SERGIO) (SERGIO) 8:15 AM 8AM KICKBOXING KICKBOXING (SERGIO) (MAYA) 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9AM 9:15 AM STRAP KICKBOXING KICKBOXING KICKBOXING KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING (GIL) (MAYA) (GIL) (MAYA) (GIL) (SERGIO) 10:30 AM 10:30 AM 10:30AM 10AM BEGINNERS BJJ BEGINNERS BJJ ART OF 8 MUAY THAI BEGINNERS BJJ (GIL) (GIL) (JAMES) (GIL) 12 PM 12 PM CLOSED FROM KICKBOXING: A 60-minute workout combining a series of ALL GYM COMBAT STRAP KICKBOXING 1130AM-330PM kickboxing techniques you will do on a heavy bag with body (Gil) (GIL) weight muscle endurance exercises. (NO CONTACT) ALL GYM COMBAT: We use the whole gym for this one. 4 PM 4 PM 4 PM 4 PM 4PM Equipment such as battle ropes, Kettlebells, agility ladder, Bungee cable, Grappling Dummies, etc. combined with STRAP KICKBOXING KIDS CLASS KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KIDS CLASS Kickboxing to train like a fighter. (NO CONTACT) (GIL) (SERGIO) (SERGIO) (GIL) (SERGIO) ART OF 8 MUAY THAI: This Class focuses on teaching you the fundamentals of Muay Thai Kickboxing. You will learn 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15PM how to hold Thai pads and gain real striking skills. -

The Death of Dueling Wade Ellett

59 60 The Death of Dueling feuds, and a chivalric code of honor emphasizing virtue.6 Eventually this code of honor evolved into the upper class and nobility’s theory of courtesy and the idea of the “gentleman”. This resulted in the adoption of one-on-one combat to settle affairs in 7 the sixteenth century. The duel of honor, as recognized from entertainment media, was based primarily on the Italian Wade Ellett Renaissance idea of the gentleman and arrived in England in the 1570s.8 The practice was welcomed by the upper classes, who had Violence in some form or another has probably always long been awaiting a method to solve disputes. But the warm existed. Civilization did not end violence, it merely provided a reception was not shared by royalty, and Queen Elizabeth I framework to ritualize and institutionalize violent acts. Once outlawed the judicial duel in 1571.9 Her attempts to remove the civilized, ritual violence became almost entirely a man’s realm.1 practice from England failed and dueling quickly gained Ritual violence took many forms; but, without a doubt, one of the popularity.10 most romanticized was the duel. Dueling differed from wartime Dueling thrived in England for nearly three centuries; violence and barroom brawls because dueling placed two however, the practice eventually came to an end in 1852, when the opponents, almost always of similar social class, against one last recorded English duel was fought. There were many another in a highly stylized form of combat.2 Fisticuffs and war contributing factors to the practice’s end. -

World Combat Games Brochure

Table of Contents 4 5 6 What is GAISF? What are the World Roles and Combat Games? responsibilities 7 8 10 Attribution Culture, ceremonies Media promotion process and festival events, and production and legacy 12 13 14 List of sports Venue Aikido at the World setup Armwrestling Combat Games Boxing 15 16 17 Judo Kendo Muaythai Ju-jitsu Kickboxing Sambo Karate Savate 18 19 Sumo Wrestling Taekwondo Wushu 4 WORLD COMBAT GAMES WORLD COMBAT GAMES 5 What is GAISF? What are the World Combat Games? The united voice of sports - protecting the interests of International A breathtaking event, showcasing Federations the world’s best martial arts and GAISF is the Global Association of International Founded in 1967, GAISF is a key pillar of the combat sports Sports Federations, an umbrella body composed wider sports movement and acts as the voice of autonomous and independent International for its 125 Members, Associate Members and Sports Federations, and other international sport observers, which include both Olympic and non- and event related organisations. Olympic sports organisations. THE BENEFITS OF THE NUMBERS OF HOSTING THE WORLD THE GAMES GAISF MULTISPORT GAMES COMBAT GAMES Up to Since 2010, GAISF has successfully delivered GAISF serves as the conduit between ■ Bring sport to life in your city multisport games for combat sports and martial International Sports Federations and host cities, ■ Provide worldwide multi-channel media exposure 35 disciplines arts, mind games and urban orientated sports. bringing benefits to both with a series of right- ■ Feature the world’s best athletes sized events that best consider the needs and ■ Establish a perfect bridge between elite sport and Approximately resources of all involved. -

1St Degree Combat Maneuvers

1st Degree Combat provoked, you expend one piece of ammunition or thrown weapon. Maneuvers Doubleshot (1 point) Adamant Mountain Bonus Action—The next ranged weapon attack you make uses two missiles instead of Heavy Combat Stance (1 point) one. You make this attack with minor disadvantage. On a hit, you deal an Stance—On each of your turns, you gain additional damage die. minor advantage on your first melee weapon attack roll using a weapon with the Heavy property. Farshot Combat Stance (1 point) Stance—When you are wielding a ranged Heavy Swing (1 point) weapon, increase its normal range by 10 feet and long range by 30 feet. Reaction—When you hit with a melee weapon attack using a weapon with the Heavy property, you can use your reaction to Guarded Draw (1 point) make an additional melee weapon attack Bonus Action—Being within 5 feet of a against a second creature that is also within hostile creature who can see you and who your reach. You have minor disadvantage on isn’t incapacitated does not give you this additional attack. disadvantage when making a ranged weapon attack. In addition, when an adjacent hostile Lean Into It (1 point) creature that you can see moves 5 feet or more away from you, you can use your Technique—Until the start of your next turn, reaction to make a ranged weapon attack you deal an extra 1d4 damage whenever you against it. hit with a weapon attack using a weapon that has the Heavy property. Mirror's Glint Mountain’s Might (2 points) Intuitive Combat Stance (1 point) Bonus Action—You regain hit points equal to 1d6 + your proficiency bonus + your Stance—You gain minor advantage on Constitution modifier (minimum 0). -

Download Article

6th International Conference on Social Network, Communication and Education (SNCE 2016) The Development and Reflection on the Traditional Martial Arts Culture Zhenghong Li1, a and Zhenhua Guo1, b 1College of Sports Science, Jishou University Renmin South Road 120, Jishou City Hunan Province, China [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Martial arts; Martial arts culture; Development; Reflection Abstract. Martial arts is an outstanding spiritual creation through the historical choice. As a kind of cultural form, it cnnotations. In this paper, using the research methods of literature, logic reasoning and so on, the interontains the rich cultural copretation of the traditional martial arts culture has been researched. The results show that The Chinese classical philosophy is the thought origin of the martial arts culture. Worshiping martial arts and advocating moral character are the important connotation of Chinese wushu culture. On the pre - qin period, contention of a hundred schools of thought in the field of ideology and culture make martial arts begin showing the cultural characteristics. The secularization of Song-Ming Neo-Confucianism makes martial arts gradually develop into a mature culture carrier. At the same time, this paper also analyzes the external martial arts’ impact on Chinese wushu; Western physical education’ misreading on Chinese wushu culture; The helpless of Chinese Wushu in In an age of extravagance and waste; The "disenchantment" of Chinese wushu culture in modern society; the condition and hope of Chinese martial arts culture. In view of this, this article calls for China should take great effort to study martial arts, refine, package and promote Chinese Wushu. -

Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China Democratic Revolution in China, Was Launched There

Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy The Great Wall of China In c. 220 BC, under Qin Shihuangdi (first emperor of the Qin dynasty), sections of earlier fortifications were joined together to form a united system to repel invasions from the north. Construction of the Great Wall continued for more than 16 centuries, up to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), National Emblem of China creating the world's largest defense structure. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. The design of the national emblem of the People's Republic of China shows Tiananmen under the light of five stars, and is framed with ears of grain and a cogwheel. Tiananmen is the symbol of modern China because the May 4th Movement of 1919, which marked the beginning of the new- Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China democratic revolution in China, was launched there. The meaning of the word David M. Darst, CFA Tiananmen is “Gate of Heavenly Succession.” On the emblem, the cogwheel and the ears of grain represent the working June 2011 class and the peasantry, respectively, and the five stars symbolize the solidarity of the various nationalities of China. The Han nationality makes up 92 percent of China’s total population, while the remaining eight percent are represented by over 50 nationalities, including: Mongol, Hui, Tibetan, Uygur, Miao, Yi, Zhuang, Bouyei, Korean, Manchu, Kazak, and Dai. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. Please refer to important information, disclosures, and qualifications at the end of this material. Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy Table of Contents The Chinese Dynasties Section 1 Background Page 3 Length of Period Dynasty (or period) Extent of Period (Years) Section 2 Issues for Consideration Page 65 Xia c. -

VADEMECUM VIENI CON ME (Con Noi)

VADEMECUM VIENI CON ME (Con Noi) 1998 – 2018 RESPONSABILE PUBBLICAZIONE A.S.D. SCUOLA RADICI DEL TAO www.scuola-radici-del-tao.it "Il saggio non è erudito, l’erudito non è saggio. Il saggio non accumula per sé; egli vive per gli altri E più si adopera per gli altri, più acquista per se; più dona agli atri, più diviene ricco" Lao Tzu, "Dao De Jing" SEDI OPERATIVE VERGIATE (VARESE) Via Sempione, 24 - Cell. 348 1045108 [email protected] ROBECCHETTO CON INDUNO (MILANO) Loc. Cascina Padregnana - Cell. 340 6849082 [email protected] A.S.D. SCUOLA RADICI DEL TAO La Scuola Radici del Tao è un’associazione fondata nel 1998 dal M° Orlando Francese, si prefigge di far conoscere, praticare e studiare tecniche e discipline che considerano l’uomo nel suo insieme di Corpo, Mente e Spirito. Lo studio e la pratica delle Arti Marziali non sono finalizzati all’esclusiva espressione della forza fisica, ma alla comprensione e all’applicazione della Filosofia che vi è alla sua base. Attraverso la pratica e lo studio, si ricercano e coltivano l’Armonia, prima con se stessi, poi con gli altri e con l’intero mondo che ci circonda e avvolge. Le discipline studiate e praticate principalmente sono: Kung fu di Chenjiagou (specifico per bambini), Taiji Quan stile Yang e Chen, Meihua Quan, San Shou, Tui Shou, combattimento tradizionale e combattimento sportivo senza KO (Qin Da), studio delle armi tradizionali (bastone, sciabola, spada, lancia, alabarda, ecc.), tecniche di rigenerazione quali: Qi Gong, Yoga, Taiji-Qi Gong, Meditazione, Massaggi Shiatsu e Ayurvedico, Floriterapia di Edward Bach.