Homestay Programme As Potential Tool for Sustainable Tourism Development?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOTC Project Pipeline 29 September 2014, Singapore

Public-Private Partnerships DOTC Project Pipeline 29 September 2014, Singapore Rene K. Limcaoco Undersecretary for Planning and Project Development Department of Transportation and Communications Key Performance Indicators 1. Reduce transport cost by 8.5% – Increase urban mass transport ridership from 1.2M to 2.2M (2016) – Development of intermodal facilities 2. Lessen logistics costs from 23% to 15% – Improve transport linkages and efficiency 3. Airport infra for 10M foreign and 56M domestic tourists – Identify and develop key airport tourism destinations to improve market access and connectivity 4. Reduce transport-related accidents – Impose standards and operating procedures TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT PLAN Awarded and for Implementation With On-going Studies • Automatic Fare Collection System • North-South Railway • Mactan-Cebu Int’l Airport • Mass Transit System Loop • LRT 1 Cavite Extension • Manila Bay-Pasig River Ferry System • MRT 7 (unsolicited; for implementation) • Integrated Transport System – South • Clark International Airport EO&M Under Procurement • LRT Line 1 Dasmariñas Extension • Integrated Transport System – Southwest • C-5 BRT • Integrated Transport System – South • LRT 2 Operations/Maintenance For Procurement of Transaction Advisors • NAIA Development For Rollout • Manila East Mass Transit System • New Bohol Airport Expansion, O&M • R1-R10 Link Mass Transit System • Laguindingan Airport EO&M • Road Transport IT Infrastructure Project Phase II • Central Spine RoRo For Approval of Relevant Government Bodies • MRT Line 3 -

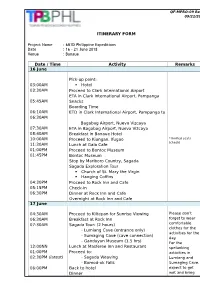

ITINERARY FORM Project Name : 6N7D Philippine Expeditions Date

QF-MPRO-09 Rev-0 09/21/2015 ITINERARY FORM Project Name : 6N7D Philippine Expeditions Date : 16 – 21 June 2018 Venue : Banaue Date / Time Activity Remarks 16 June Pick-up point: 03:00AM . Hotel 03:30AM Proceed to Clark International Airport ETA in Clark International Airport, Pampanga 05:45AM Snacks Boarding Time 06:10AM ETD in Clark International Airport, Pampanga to 06:30AM Bagabag Airport, Nueva Vizcaya 07:30AM ETA in Bagabag Airport, Nueva Vizcaya 08:40AM Breakfast in Banaue Hotel 10:00AM Proceed to Kiangan, Ifugao * limited seats (check) 11:30AM Lunch at Gaia Cafe 01:00PM Proceed to Bontoc Museum 01:45PM Bontoc Museum Stop by Marlboro Country, Sagada Sagada Exploration Tour . Church of St. Mary the Virgin . Hanging Coffins 04:30PM Proceed to Rock Inn and Cafe 05:15PM Check-in 06:30PM Dinner at Rock Inn and Cafe Overnight at Rock Inn and Cafe 17 June 04:30AM Proceed to Kiltepan for Sunrise Viewing Please don’t 06:30AM Breakfast at Rock Inn forget to wear 07:30AM Sagada Tour: (2 hours) comfortable clothes for the - Lumiang Cave (entrance only) activities for the - Sumaging Cave (cave connection) day. - Ganduyan Museum (1.5 hrs) For the 12:00NN Lunch at Masferee Inn and Restaurant spelunking 01:00PM Proceed to: activities in 02:30PM (latest) - Sagada Weaving Lumiang and - Bomod-ok Falls Sumaging Cave, 06:00PM Back to hotel expect to get Dinner wet and bring extra clothes. 18 June Breakfast at hotel Proceed to: - Ganduyan Museum - Sagada Underground River Lunch Proceed to: - Lake Danum - Pongas Falls Back to hotel Dinner 19 June Proceed to Ifugao Rice Terraces Tour . -

1St Quarter Report

Republic of the Philippines Regional Development Council 02 Regional Project Monitoring and Evaluation System Tuguegarao City RPMES/RME REPORT FIRST QUARTER 2009 Rehiyon Dos Kumikilos...Ayos! TABLE OF CONTENTS T I T L E PAGE I. Main Report 1 II. Individual Project Profiles A. Foreign-Assisted Programs/Projects 1. DAR-ADB Agrarian Communities Project (ARCP) . 9 2. DAR-JBIC Agrarian Reform Infra Support Project (ARISP) II . 11 3. Austrian Assisted DPWH Bridge Const./Replacement Project . 13 4. DENR-ADB Integrated Coastal Resource Management Project . 14 B. Major Nationally-Funded Programs/Projects 1. Super Region Program 1.1 North Luzon Agribusiness Quadrangle (NLAQ) 1.1.a Bagabag Airport Development Project . 17 1.1.b Port Irene Rehabilitation and Development Project . 18 1.1.c Government Hospital Upgrading . 19 1.2 Cyber Corridor Program . 20 2. 2006 PGMA-SONA Projects 2.1 Small Water Impounding Projects . 22 3. 2007 PGMA-SONA Projects 3.1 Construction of Farm-to-Market Roads . 25 3.2 Sta. Ana Airport Development Project . 26 4. Livelihood and Employment Program 4.1 Self-Employment Assistance - Kaunlaran Program . 28 4.2 Promotion of Rural Employment through Self-Employment & Entrepreneurship 29 Development (PRSEED) . 4.3 Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program . 30 4.4 Workers Income Augmentation Program . 31 5. Other Major Infra Support Projects 5.1 CY 2008 School Building Program . 33 5.2 CY 2007 School Building Program . 34 5.3 Addalam River Irrigation Project . 36 5.4 Delfin Albano Bridge . 38 RPMES/RME REPORT 1ST QUARTER CY 2009 I. INTRODUCTION The 1st Quarter CY 2009 RPMES/RME Report presents the implementation status of nineteen (19) major regional development programs and projects funded by the National Government (GOP) Funds and Official Development Assistance (ODA). -

Regional Economic Developments Philippines

REPORT ON REGIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS IN THE PHILIPPINES 2017 Department of Economic Research Regional Operations Sub‐Sector Contents Executive Summary ii Foreword iv BSP Regional Offices and Branches v Philippines: Regional Composition vi Key Regional Developments 1 Real Sector: Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) 1 Agriculture, Livestock, Poultry and Fishery 3 Construction 11 Labor and Employment 14 Box Article: Poverty Incidence & Unemployment Trends in the Regions 16 Fiscal Sector: Receipts and Expenditures of LGUs 20 Monetary Sector: Inflation 21 External Sector: Approved Foreign Investments 22 Financial Sector: Banking and Microfinance 24 Opportunities and Challenges 27 Conclusion 69 Statistical Annexes i Executive Summary The Philippine economy continued its solid growth track, posting a 6.7 percent gross domestic product (GDP) expansion in 2017, within the growth target range of the national government (NG) of 6.5 percent to 7.5 percent. All regions exhibited positive performance in 2017, led by CAR, Davao Region, Western Visayas, SOCCSKSARGEN, ARMM, Cagayan Valley, CALABARZON, MIMAROPA and Caraga. Growth in the regions has been broad‐based and benefited largely from the remarkable improvement in the agriculture sector. Favorable weather conditions and sufficient water supply supported strong yields of major crops. Palay and corn production grew by 16.2 percent and 9.6 percent in 2017, from previous year’s contraction of 4.5 percent and 4.0 percent, respectively. Swine and fish production grew, albeit, at a slower pace while chicken production rose amid high demand for poultry products in Eastern and Central Visayas, Zamboanga Peninsula and Caraga regions. However, cattle production contracted in 2017 due to typhoon damage, incidence of animal deaths, less stocks available, and unfavorable market prices, among others. -

ASEAN Tourism Investment Guide

ASEAN Tourism Investment Guide Design and Layout Sasyaz Kreatif Sdn. Bhd. (154747-K) Printer Sasyaz Holdings Sdn. Bhd. (219275-V) [email protected] Copyright © ASEAN National Tourism Organisations Published by : ASEAN National Tourism Organisations First published April 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. C o n t e n t s Page Preface 5 Asean Fast Fact 6 Brunei Darussalam 7 Cambodia 11 Indonesia 31 Lao PDR 67 Malaysia 81 Myanmar 115 Philippines 137 Singapore 199 Thailand 225 Viet Nam 241 P r e f a c e Tourism is one of the main priority sectors for ASEAN economic integration as envisaged in the Vientiane Action Programme (VAP). The ASEAN National Tourism Organizations (ASEAN NTOs) formulated a Plan of Action for ASEAN Co-operation in Tourism which includes the facilitation of investment within the region. Tourism has become a key industry and an important generator of income and employment for countries in the region. The rapid growth of tourism in recent years has attracted the interest of potential investors who are keen to be involved in this industry. One of the measures under the Implementation of Roadmap for Integration of Tourism Sector (Tourism Investment) is the Incentives for Development of Tourism Infrastructure (Measure no. 20). The objective of this measure is to provide incentives for the development of tourism infrastructure so as to encourage private investment in the ASEAN countries coming from investors within and outside the region. -

Xxiii. Department of Transportation and Communications

XXIII. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATIONS A. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY For general administration and support, support to operations, and operations, including locally-funded and foreign-assisted projects as indicated hereunder................................................................................................. P 20,259,960,000 --------------- New Appropriations, by Program/Project ====================================== Current_Operating_Expenditures Maintenance and Other Personal Operating Capital Services___ ___Expenses____ ____Outlays____ _____Total A. PROGRAMS I. General Administration and Support a. General Administration and Support Services P 581,717,000 P 796,895,000 P 70,026,000 P 1,448,638,000 --------------- --------------- --------------- --------------- Sub-total, General Administration and Support 581,717,000 796,895,000 70,026,000 1,448,638,000 --------------- --------------- --------------- --------------- II. Support to Operations a. Policy Formulation 37,453,000 45,096,000 1,000,000 83,549,000 b. Air Transportation Services 31,250,000 31,250,000 c. Land Transportation Services 14,129,000 551,087,000 565,216,000 d. Regulation of Public Land Transportation 300,000 300,000 e. Protection of Philippine Coast 400,000 400,000 --------------- --------------- --------------- --------------- Sub-total, Support to Operations 51,582,000 628,133,000 1,000,000 680,715,000 --------------- --------------- --------------- --------------- III. Operations a. Land Transportation Services 249,573,000 121,838,000 970,000 -

ISSN-2094-6163 PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY MARKETING INFRASTRUCTURE and FACILITIES 2014

ISSN-2094-6163 PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY MARKETING INFRASTRUCTURE and FACILITIES 2014 Republic of the Philippines PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY CVEA Bldg., East Avenue, Quezon City Agricultural Marketing Statistics Analysis Division (AMSAD) Telefax: 376-6365 [email protected] http://psa.gov.ph PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY MARKETING INFRASTRUCTURE and FACILITIES 2014 TERMS OF USE Marketing Infrastructure and Facilities 2014 is a publication of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). The PSA reserves exclusive right to reproduce this publication in whatever form. Should any portion of this publication be included in a report/article, the title of the publication and the BAS should be cited as the source of data. The PSA will not be responsible for any information derived from the processing of data contained in this publication. ISSN-2094-6163 Please direct technical inquiries to the Office of the National Statistician Philippine Statistics Authority CVEA Bldg., East Avenue Quezon City Philippines Email: [email protected] Website: www.psa.gov.ph PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY MARKETING INFRASTRUCTURE and FACILITIES 2014 FOREWORD This report is an update of information on the Marketing Infrastructure and Facilities published in August 2010 by the former Bureau of Agricultural Statistics. It aimed at providing farmers, traders and policy makers the regional and national data on marketing infrastructure and facilities for cereals, livestock and fisheries. Some of the data covered the period 2009-2014, while others have shorter periods due to data availability constraints. The first part of this report focuses on marketing infrastructure, while the second part presents the marketing facilities for cereals, livestock and fisheries. The information contained in this report were sourced primarily from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) and other agencies, namely, National Food Authority (NFA), Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), Philippine Ports Authority (PPA), Bureau of Animal Industry (BAI) and National Dairy Authority (NDA). -

Ppp) Infrastructure Development Projects in the Republic of the Philippines

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) NATIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (NEDA) DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS (DPWH) PREPARATORY SURVEY FOR PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP (PPP) INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY DECEMBER 2010 CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. MITSUBISHI RESEARCH INSTITUTE, INC. EXCHANGE RATE May 2010 1 PhP = 1.97 Japan Yen 1 US$ = 46.21 Philippine Peso 1 US$ = 90.85 Japan Yen Central Bank of the Philippines PREFACE The Government of Japan decided to conduct the “Preparatory Survey for Public‐Private Partnership (PPP) Infrastructure Development Projects in the Republic of the Philippines” and entrusted the Study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched a Study Team headed by Mr. Mitsuo Kiuchi of CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. from February 2010 to November 2010. The Study Team held discussions with the officials of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) and other officials of the Philippine Government and conducted field surveys, data gathering and analysis, based on which the Study Team identified bottlenecks in the PPP process and candidate PPP projects. The Study Team recommended possible priority PPP projects for ODA funding, roadmap for promotion of PPP projects and technical support program. The Study Team also held trainings, workshops and stakeholders meetings to solicit opinions from different stakeholders. Upon returning to Japan, the Study Team prepared this final report which summarized the results of the Study. I hope that this report will contribute to the development and promotion of PPP projects and to the enhancement of friendly relationship between our two countries. -

Microphone in the Mud

Microphone in the Mud by Laura C. Robinson with Gary Robinson LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION AND CONSERVATION SPECIAL PUBLICATION NO. 6 PUBLISHED AS A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822 USA http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I PRESS 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822-1888 USA © All text and images are copyright to the authors, 2013 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Cover design by Laura C. Robinson Cover photograph of the author working with Agta speakers in Isabela province Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data ISBN 978-0-9856211-3-1 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4578 PREFACE All of the events in this book are true. Although about half of it was written while it took place, and the rest is based on meticulous notes, some of the dialogue and detailed descriptions are necessarily approximations. In addition, some of the timeline has been condensed (for example, combining the events of two days into one) to preserve narrative flow. Finally, the names of many characters have been changed. In a few cases, identifying details have also been changed to preserve anonymity. Gary Robinson, my father, did much of the work of editing the journal entries I kept into book form. He also helped edit much of the text, injecting his own experiences based on his three-week trip which takes place in the middle of this narrative. -

Philippine Transport Sector: Developments and Project Pipeline

Philippine Transport Sector September 2015 Philippine Transport Sector: Developments and Project Pipeline Department of Transportation and Communications September 2015 2 Transport development plan Data Driven Better management and processing of information that makes franchising transparent improving competition Improve the collection of trip data to determine optimal routes and supply information More Lines, More Connections Increase rail transportation network to increase access and mobility New Buses and New Routes INITIATIVES Bus Rapid Transit Projects Seamless Terminal Transfers Provision of new provincial bus routes to correct supply gaps caused by franchise restrictions Bus routes will be introduced on corridors that have no or limited public transportation Better Services Providing a unified ticketing system Creating better interconnections Provide better service levels to the riding public by reducing headway 3 Transport development plan Key Performance Indicators Reduce transport cost by 8.5% Increase urban mass transport ridership from 1.2mn to 2.2mn (2016) Development of intermodal facilities Lessen logistics costs from 23% to 15% Improve transport linkages and efficiency GOALS Airport infrastructure for 10mn foreign and 56mn domestic tourists Identify and develop key airport tourism destinations to improve market access and connectivity Reduce transport-related accidents Impose standards and operating procedures 4 Major accomplishments As of 15 September 2015 Full operationalization of Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA) Terminal 3 Upgrading of NAIA Terminal 1 Civil aviation upgrades Upgrade of Philippine civil aviation to Category 1 by the United States Federal Aviation Administration AVIATION SECTOR NEDA Approval of Clark International Airport – Passenger Terminal Building (PTB) A new passenger terminal building is to be constructed in Clark which will serve 3mn passengers yearly to meet growing demand in Central and North Luzon. -

DPWH Atlas 1,000,000 1,000,000

IV. DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS A. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY Current Operating Expenditures ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ Maintenance and Other Personal Operating Capital Services Expenses Outlays Total ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ B. PROJECT(s) I. Locally-Funded Project(s) a. National Arterial and Secondary National Roads and Bridges 61,312,377,000 61,312,377,000 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ 1. Urgent National Arterial/Secondary Roads and Bridges 35,942,030,000 35,942,030,000 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ a. Traffic Decongestion 4,378,406,000 4,378,406,000 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ 1. Metro Manila 1,965,430,000 1,965,430,000 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ a. Construction/ Improvement (Concreting/ Widening) / Rehabilitation of NAIA Expressway and other Major Roads in Metro Manila 300,000,000 300,000,000 b. Opening/ Concreting of Taguig Diversion Road, Taguig 60,000,000 60,000,000 c. Concreting of Congressional Avenue Extension, Quezon City 215,000,000 215,000,000 d. Construction (Opening) of Circumferential Road 6 (C-6) Including RROW 150,000,000 150,000,000 e. Construction of Pres. Garcia Avenue(C-5) Extension 250,000,000 250,000,000 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ 1. Sucat to Coastal Section including ROW 187,000,000 187,000,000 2. C.P. Garcia to Magsaysay Avenue 63,000,000 63,000,000 f. Widening/Concreting of McArthur Highway (Manila North Road) including Traffic Management 940,430,000 940,430,000 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ 1. Meycauayan (Bulacan) to Mabalacat (Pampanga), (Intermittent Sections) 745,000,000 745,000,000 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ a. Civil Works 595,000,000 595,000,000 b. Traffic Management 150,000,000 150,000,000 2. Tarlac Province (Intermittent Sections) 165,430,000 165,430,000 3. Urdaneta City, Pangasinan including ROW 30,000,000 30,000,000 g. -

General Appropriations Act, Fy 2010 Xviii. Department of Public Works and Highways

GENERAL APPROPRIATIONS ACT, FY 2010 XVIII. DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS A. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY For general administration and support, support to operations, and operations including locally-funded and foreign-assisted projects, as indicated hereunder.....................................................................................................P 126,930,988,000 ---------------- New Appropriations, by Program/Project ====================================== Current Operating Expenditures Maintenance and Other Personal Operating Capital Services Expenses Outlays Total A. PROGRAMS I. General Administration and Support a. General Administration and Support Services P 557,568,000 P 315,754,000 P P 873,322,000 --------------- --------------- ---------------- Sub-Total, General Administration and Support 557,568,000 315,754,000 873,322,000 --------------- --------------- ---------------- II. Support to Operations a. Policy Formulation, Program Planning and Standards Development 209,960,000 15,614,000 225,574,000 b. Regional Support (Planning and Design, Construction, Maintenance and Material Quality Control and Hydrology Divisions) 198,615,000 2,871,000 201,486,000 c. Operational Support for the Maintenance and Repair of Infrastructure Facilities and Other Related Activities 229,430,000 9,790,000 239,220,000 --------------- --------------- ---------------- Sub-Total, Support to Operations 638,005,000 28,275,000 666,280,000 --------------- --------------- ---------------- III. Operations a. Construction, Maintenance, Repair