The Internet in Flux

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2017 Annual Report 2017 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Every now and then I am introduced to someone who knows, kind of, who I am and what I do and they instinctively ask, ‘‘How are things at Saga?’’ (they pronounce it ‘‘say-gah’’). I am polite and correct their pronunciation (‘‘sah-gah’’) as I am proud of the word and its history. This is usually followed by, ‘‘What is a ‘‘sah-gah?’’ My response is that there are several definitions — a common one from 1857 deems a ‘‘Saga’’ as ‘‘a long, convoluted story.’’ The second one that we prefer is ‘‘an ongoing adventure.’’ That’s what we are. Next they ask, ‘‘What do you do there?’’ (pause, pause). I, too, pause, as by saying my title doesn’t really tell what I do or what Saga does. In essence, I tell them that I am in charge of the wellness of the Company and overseer and polisher of the multiple brands of radio stations that we have. Then comes the question, ‘‘Radio stations are brands?’’ ‘‘Yes,’’ I respond. ‘‘A consistent allusion can become a brand. Each and every one of our radio stations has a created personality that requires ongoing care. That is one of the things that differentiates us from other radio companies.’’ We really care about the identity, ambiance, and mission of each and every station that belongs to Saga. We have radio stations that have been on the air for close to 100 years and we have radio stations that have been created just months ago. -

Freepint Report: Product Review of Factiva

FreePint Report: Product Review of Factiva December 2014 Product Review of Factiva In-depth, independent review of the product, plus links to related resources “...has some 32,000 sources spanning all forms of content of which thousands are not available on the free web. Some source archives go back to 1951...” [SAMPLE] www.freepint.com © Free Pint Limited 2014 Contents Introduction & Contact Details 4 Sources - Content and Coverage 5 Technology - Search and User Interface 8 Technology - Outputs, Analytics, Alerts, Help 18 Value - Competitors, Development & Pricing 29 FreePint Buyer’s Guide: News 33 Other Products 35 About the Reviewer 36 ^ Back to Contents | www.freepint.com - 2 - © Free Pint Limited 2014 About this Report Reports FreePint raises the value of information in the enterprise, by publishing articles, reports and resources that support information sources, information technology and information value. A FreePint Subscription provides customers with full access to everything we publish. Customers can share individual articles and reports with anyone at their organisations as part of the terms and conditions of their license. Some license levels also enable customers to place materials on their intranets. To learn more about FreePint, visit http://www.freepint.com/ Disclaimer FreePint Report: Product Review of Factiva (ISBN 978-1-78123-181-4) is a FreePint report published by Free Pint Limited. The opinions, advice, products and services offered herein are the sole responsibility of the contributors. Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the publication, the publishers cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions. Except as covered by subscriber or purchaser licence agreement, this publication MAY NOT be copied and/or distributed without the prior written agreement of the publishers. -

Read All About It! Understanding the Role of Media in Economic Development

Kyklos_2004-01_UG2+UG3.book Seite 21 Mittwoch, 28. Januar 2004 9:15 09 KYKLOS, Vol. 57 – 2004 – Fasc. 1, 21–44 Read All About It! Understanding the Role of Media in Economic Development Christopher J. Coyne and Peter T. Leeson* I. INTRODUCTION The question of what factors lead to economic development has been at the center of economics for over two centuries. Adam Smith, writing in 1776, at- tempted to determine the factors that led to the wealth of nations. He concluded that low taxes, peace and a fair administration of justice would lead to eco- nomic growth (1776: xliii). Despite the straightforward prescription put forth by Smith, many countries have struggled to achieve the goal of economic pros- perity. One can find many examples – Armenia, Bulgaria, Moldova, Romania and Ukraine to name a few – where policies aimed at economic development have either not been effectively implemented or have failed. If the key to eco- nomic development is as simple as the principles outlined by Smith, then why do we see many countries struggling to achieve it? The development process involves working within the given political and economic order to adopt policies that bring about economic growth. Given that political agents are critical to the process, the development of market institu- tions that facilitate economic growth is therefore a problem in ‘public choice’. There have been many explanations for the failure of certain economies to de- velop. A lack of investment in capital, foreign financial aid (Easterly 2001: 26– 45), culture (Lal 1998) and geographic location (Gallup et al. 1998) have all been postulated as potential explanations for the failure of economies to de- velop. -

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2016 Annual Report 2016 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Well…. here we go. This letter is supposed to be my turn to tell you about Saga, but this year is a little different because it involves other people telling you about Saga. The following is a letter sent to the staff at WNOR FM 99 in Norfolk, Virginia. Directly or indirectly, I have been a part of this station for 35+ years. Let me continue this train of thought for a moment or two longer. Saga, through its stockholders, owns WHMP AM and WRSI FM in Northampton, Massachusetts. Let me share an experience that recently occurred there. Our General Manager, Dave Musante, learned about a local grocery/deli called Serio’s that has operated in Northampton for over 70 years. The 3rd generation matriarch had passed over a year ago and her son and daughter were having some difficulties with the store. Dave’s staff came up with the idea of a ‘‘cash mob’’ and went on the air asking people in the community to go to Serio’s from 3 to 5PM on Wednesday and ‘‘buy something.’’ That’s it. Zero dollars to our station. It wasn’t for our benefit. Community outpouring was ‘‘just overwhelming and inspiring’’ and the owner was emotionally overwhelmed by the community outreach. As Dave Musante said in his letter to me, ‘‘It was the right thing to do.’’ Even the local newspaper (and local newspapers never recognize radio) made the story front page above the fold. Permit me to do one or two more examples and then we will get down to business. -

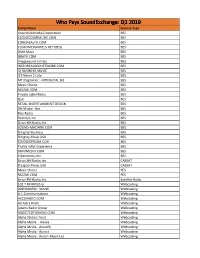

Who Pays SX Q3 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q3 2019 Entity Name License Type AMBIANCERADIO.COM BES Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES F45 Training Incorporated BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It's Never 2 Late BES Jukeboxy BES MANAGEDMEDIA.COM BES MIXHITS.COM BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES Music Maestro BES Music Performance Rights Agency, Inc. BES MUZAK.COM BES NEXTUNE.COM BES Play More Music International BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Startle International Inc. BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio #1 Gospel Hip Hop Webcasting 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 411OUT LLC Webcasting 630 Inc Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting AD VENTURE MARKETING DBA TOWN TALK RADIO Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting africana55radio.com Webcasting AGM Bakersfield Webcasting Agm California - San Luis Obispo Webcasting AGM Nevada, LLC Webcasting Agm Santa Maria, L.P. Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting -

Demokratiereport

THE KAS DEMOCRACY REPORT 2008 MEDIA AND DEMOCRACY VOLUME II PUBLISHER Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. EDITORS Karsten Grabow Christian E. Rieck www.kas.de © 2008 Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e. V. Sankt Augustin / Berlin All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanically, without written permission of the publisher. Layout: Switsch Kommunikationsdesign, Cologne Typesetting: workstation gmbh, Bonn This publication was printed with financial support of the Federal Republic of Germany. Printed in Germany. All contributions in this volume reflect the opinion of their authors, not necessarily that of the KAS, unless otherwise stated. ISBN: 978-3-940955-25-8 CONTENTS 3 | PREFACE 5 | INTRODUCTION: OBJECTIVES, METHOD AND STUDY DESIGN 13 | COUNTRY REPORTS BY REGION 15 | AFRICA 17 | NIGERIA 33 | SENEGAL 43 | ASIA 45 | CHINA 59 | GEORGIA 72 | MALAYSIA 82 | PHILIPPINES 94 | THAILAND 101 | EUROPE 103 | BULGARIA 116 | POLAND 126 | RUSSIA 135 | UKRAINE 143 | LATIN AMERICA 145 | BOLIVIA 155 | BRAZIL 165 | VENEZUELA 177 | MIDDLE EAST 179 | EGYPT 189 | TURKEY 199 | ANALYSIS: MEDIA AND MEDIA FREEDOM – DEVELOPMENTS AND TRENDS 214 | PROMOTING FREE MEDIA: THE MEDIA PROGRAMME OF THE KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG 222 | APPENDIX: QUESTIONNAIRE 227| CONTRIBUTORS 3 PREFACE The KAS Democracy Report describes the state of key democracy sectors in partner countries of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. With the publication of the first three volumes, Media and Democracy (2005), Rule of Law (2006), and Parties and Democracy (2007) the first cycle of the series was completed. This year, the cycle starts again with a study on the media, although the selection of countries differs to some extent from that of 2005. -

2015 Annual Report 2015 Annual Letter to Our Fellow Shareholders

2015 Annual Report 2015 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Although another year has zoomed by, 2015 seems like it was 2014 all over again. The good news is that we are still here and we have used some of our excess cash for significant and cogent acquisitions. We will get into that shortly, but first a small commercial about broadcasting. I have always, since childhood, been fascinated by magic and magicians. I even remember, very early in my life, reading the magazine PARADE that came with the Sunday newspaper. Inside the back page were small ads that promoted everything from the ‘‘best new rug shampooer’’ to one that seemed to run each week. It was about a three inch ad and the headline always stopped me -- ‘‘MYSTERIES OF THE UNIVERSE REVEALED!’’...Wow... All I had to do was write away and some organization called the Rosicrucian’s would send me a pamphlet and correspondent courses revealing all to me. Well, my mother nixed that idea really fast. It didn’t stop my interest in magic and mysticism. I read all I could about Harry Houdini and, especially, Howard Thurston. Orson Welles called Howard Thurston ‘‘The Master’’ and, though today he is mostly forgotten except among magicians, he was truly a gifted magician and a magical performer. His competitor was Harry Houdini, whose name survived though his magic had a tragic end. If you are interested, you should take some time and research these two performers. In many ways, their magic and their shows tie into what we do today in both radio and TV. -

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making PREMS 162317

INFORMATION DISORDER : Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making PREMS 162317 ENG Council of Europe report Claire Wardle, PhD Hossein Derakhshan DGI(2017)09 Information Disorder Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking By Claire Wardle, PhD and Hossein Derakhshan With research support from Anne Burns and Nic Dias September 27, 2017 The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing from the Directorate of Communications (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). Photos © Council of Europe Published by the Council of Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex www.coe.int © Council of Europe, October, 2017 1 Table of content Author Biographies 3 Executive Summary 4 Introduction 10 Part 1: Conceptual Framework 20 The Three Types of Information Disorder 20 The Phases and Elements of Information Disorder 22 The Three Phases of Information Disorder 23 The Three Elements of Information Disorder 25 1) The Agents: Who are they and what motivates them? 29 2) The Messages: What format do they take? 38 3) Interpreters: How do they make sense of the messages? 41 Part 2: Challenges of filter bubbles and echo chambers 49 Part 3: Attempts at solutions 57 Part 4: Future trends 75 Part 5: Conclusions 77 Part 6: Recommendations 80 Appendix: European Fact-checking and Debunking Initiatives 86 References 90 2 Authors’ Biographies Claire Wardle, PhD Claire Wardle is the Executive Director of First Draft, which is dedicated to finding solutions to the challenges associated with trust and truth in the digital age. -

Sourcebook with Marie's Help

AIB Global Broadcasting Sourcebook THE WORLDWIDE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DIRECTORY | TV | RADIO | CABLE | SATELLITE | IPTV | MOBILE | 2009-10 EDITION WELCOME | SOURCEBOOK AIB Global WELCOME Broadcasting Sourcebook THE WORLDWIDE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DIRECTORY | TV | RADIO | CABLE | SATELLITE | IPTV | MOBILE | 2009 EDITION In the people-centric world of broadcasting, accurate information is one of the pillars that the industry is built on. Information on the information providers themselves – broadcasters as well as the myriad other delivery platforms – is to a certain extent available in the public domain. But it is disparate, not necessarily correct or complete, and the context is missing. The AIB Global Broadcasting Sourcebook fills this gap by providing an intelligent framework based on expert research. It is a tool that gets you quickly to what you are looking for. This media directory builds on the AIB's heritage of more than 16 years of close involvement in international broadcasting. As the global knowledge The Global Broadcasting MIDDLE EAST/AFRICA network on the international broadcasting Sourcebook is the Richie Ebrahim directory of T +971 4 391 4718 industry, the AIB has over the years international TV and M +971 50 849 0169 developed an extensive contacts database radio broadcasters, E [email protected] together with leading EUROPE and is regarded as a unique centre of cable, satellite, IPTV information on TV, radio and emerging and mobile operators, Emmanuel researched by AIB, the Archambeaud platforms. We are in constant contact -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

55 the Commission Received Two Reports, One from the Flemish

BELGIUM The Commission received two reports, one from the Flemish Community (BE-FL – Vlaamse Gemeenschap) and one from the French Community of Belgium (BE-FR – Communauté française de Belgique). No report was received from the German-speaking Community. Number of identified channels Reference period BE-VL = 48 2007/2008 BE-FR = 25 BELGIUM FLEMISH COMMUNITY PART 1 - Statistical data Number of channels identified: 48 Reference period: 2007/2008 EW (%TQT) IP (%TQT) RW(%IP) Broadcaster Channel 2007 2008 2007 2008 2007 2008 ACTUA - TV Actua TV EX EX EX EX EX EX BELGIAN BUSINESS TELEVISION Kanaal Z 100,0%100,0% 26,6% 27,3% 100,0%100,0% BOX ENTERTAINMENT Kinepolis TV 1 NC NO NC NO NC NO BOX ENTERTAINMENT Kinepolis TV 2 NC NO NC NO NC NO EURO 1080 Euro 1080 NO 100,0% NO 64,0% NO 100,0% EURO 1080 Exqi / Exqi VL. 95,0% 98,0% 38,0% 32,0% 100,0%100,0% EURO 1080 Exqi Culture NC 98,0% NC 32,0% NC 100,0% EURO 1080 Exqi Sport NC 100,0% NC 69,0% NC 100,0% EURO 1080 HD NL NC NC NC NC NC NC EURO 1080 HD1 100,0% NC 56,0% NC 100,0% NC EURO 1080 HD2 NC NC NC NC NC NC EbS Europe by Satellite (version in EUROPEAN COMMISSION EX EX EX EX EX EX Dutch) EVENT TV VLAANDEREN Liberty TV Vlaanderen 89,3% 87,4% 10,7% 12,6% 89,2% 92,6% KUST TELEVISIE VZW Kust Televisie 100,0%100,0% NC NC NC NC LIFE ! TV BROADCASTING COMPANY NV Life! TV 100,0%100,0% 13,0% 13,0% 100,0%100,0% MEDIA AD INFINITUM Vitaliteit 81,0% 76,0% 97,0% 94,0% 100,0%100,0% MEDIA AD INFINITUM Vitaya 55,0% 71,0% 85,0% 94,0% 100,0% 92,0% MTV NETWORKS BELGIUM TMF Live HD NC 98,0% NC 11,8% NC 100,0% MTV NETWORKS