Conclusion - Vi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Courses Taught at Both the Undergraduate and the Postgraduate Levels

Jadavpur University Faculty of Arts Department of History SYLLABUS Preface The Department of History, Jadavpur University, was born in August 1956 because of the Special Importance Attached to History by the National Council of Education. The necessity for reconstructing the history of humankind with special reference to India‘s glorious past was highlighted by the National Council in keeping with the traditions of this organization. The subsequent history of the Department shows that this centre of historical studies has played an important role in many areas of historical knowledge and fundamental research. As one of the best centres of historical studies in the country, the Department updates and revises its syllabi at regular intervals. It was revised last in 2008 and is again being revised in 2011.The syllabi that feature in this booklet have been updated recently in keeping with the guidelines mentioned in the booklet circulated by the UGC on ‗Model Curriculum‘. The course contents of a number of papers at both the Undergraduate and Postgraduate levels have been restructured to incorporate recent developments - political and economic - of many regions or countries as well as the trends in recent historiography. To cite just a single instance, as part of this endeavour, the Department now offers new special papers like ‗Social History of Modern India‘ and ‗History of Science and Technology‘ at the Postgraduate level. The Department is the first in Eastern India and among the few in the country, to introduce a full-scale specialization on the ‗Social History of Science and Technology‘. The Department recently qualified for SAP. -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known. -

Gopal Krishna Gokhale: Moderate Leader of Modern India

Shivaji University Centre for Gandhian Studies & Department of Political Science Organizes National Seminar Gopal krishna Gokhale: Moderate leader of Modern India 3rd & 4th February 2015 Centre for Gandhian Studies & Department of Political Science of Shivaji University is happy to announce a two days National Seminar on ‘Gopal Krisna Gokhale: Moderate leader of Modern India’ on 3rd & 4th February 2015. This is a tribute to Gopal krisna Gokhale on the occasion of Centenary Commemoration Year. Gopal Krishna Gokhale was one of the important makers of modern India & a leader of moderates. Mahatma Gandhi considered him, his Political Guru. Until his demise on 19th February 1914; he made sincere efforts to establish Parliamentary democracy and welfare State in India. He worked relentlessly for the awakening of Indian masses, may it be through his writings in Sudharak or through educational institutes. His Servants of India Society set an example of selfless social service. He was a shining star of Indian National Congress and fought the battle of moderation uncompromisingly. Mahatma Gandhi’s statement, ‘My life is my message’, is equally applicable to his Guru. During his formative years Gopal Krisna Gokhale lived and studied at Kolhapur and Kagal. His ideas and life was shaped at Kolhapur, which helped him to lead the National movement. Gokhale was a national leader and will be remembered as a national leader, but his roots in Kolhapur motivated us to organize this National Seminar. All those interested in the subject are requested to join us in our venture as participant or as paper reader. Sub themes of the Seminar 1. -

Gopal Krishna Gokhale)

Indian Political Thought (Gopal Krishna Gokhale) For By B.A. (Pol.Sc.(Hons.) G K Jha Degree Part-I, Paper-I Asst. Prof. Deptt. Of Pol. Sc. Marwari College,Darbhanga E mail:[email protected] His Life and Times • Born in a middle class family in Ratnagiri district of modern Maharashtra on May 9,1866. • A visionary statesman and articulate political thinker • Disciple of M G Ranade from 1887-1901 • A practitioner of Moderate kind of Politics and stood for constitutional method of political agitation. • He became the President of Indian National Congress in 1905. • He edited some of the popular journal of his time and that included sudharak and Journal of Sarvajanik Sabha. His contributions • He established Servants of India Society in 1905 so that educated young men could be trained for the public services and can also be taught the virtue of self-sacrifice. • Took keen interest in the issues and problems of Labour and at the request of Mahatma Gandhi, Gokhale visited South Africa in 1912 to raise the problems of Indians Settled there. • Just after the return from Africa,Gokhale became severe ill and died in the year 1915. Gokhale as Political Thinker • Gokhale was not a political thinker in strict sense of term as we use for Plato,Aristotle,Locke etc. • He did not any political commentaries or work as like Tilak’s ‘Geeta Rahasya’ or Gandhi’s ‘Hind Swaraj’. • What he wrote as an articles became the only reference to draw his political ideas. • He made a several reference on socio-economic issues or even the burning issues of the time. -

Effect of Divergent Ideologies of Mahatma Gandhi and Muhammad Iqbal on Political Events in British India (1917-38)

M.L. Sehgal, International Journal of Research in Engineering, IT and Social Sciences, ISSN 2250-0588, Impact Factor: 6.565, Volume 09 Issue 01, January 2019, Page 315-326 Effect of Divergent Ideologies of Mahatma Gandhi and Muhammad Iqbal on Political Events in British India (1917-38) M. L. Sehgal (Fmrly: D. A. V. College, Jalandhar, Punjab (India)) Abstract: By 1917, Gandhi had become a front rung leader of I.N.C. Thereafter, the ‘Freedom Movement’ continued to swirl around him till 1947. During these years, there happened quite a number of political events which brought Gandhi and Iqbal on the opposite sides of the table. Our stress would , primarily, be discussing as to how Gandhi and Iqbal reacted on these political events which changed the psych of ‘British Indians’, in general, and the Muslims of the Indian Subcontinent in particular.Nevertheless, a brief references would, also, be made to all these political events for the sake of continuity. Again, it would be in the fitness of the things to bear in mind that Iqbal entered national politics quite late and, sadly, left this world quite early(21 April 1938), i.e. over 9 years before the creation of Pakistan. In between, especially in the last two years, Iqbal had been keeping indifferent health. So, he might not have reacted on some political happenings where we would be fully entitled to give reactions of A.I.M.L. and I.N.C. KeyWords: South Africa, Eghbale Lahori, Minto-Morley Reform Act, Lucknow Pact, Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms, Ottoman Empire, Khilafat and Non-Cooperation Movements, Simon Commission, Nehru Report, Communal Award, Round Table Conferences,. -

Dadabhai Naoroji

UNIT – IV POLITICAL THINKERS DADABHAI NAOROJI Dadabhai Naoroji (4 September 1825 – 30 June 1917) also known as the "Grand Old Man of India" and "official Ambassador of India" was an Indian Parsi scholar, trader and politician who was a Liberal Party member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom House of Commons between 1892 and 1895, and the first Asian to be a British MP, notwithstanding the Anglo- Indian MP David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre, who was disenfranchised for corruption after nine months. Naoroji was one of the founding members of the Indian National Congress. His book Poverty and Un-British Rule in India brought attention to the Indian wealth drain into Britain. In it he explained his wealth drain theory. He was also a member of the Second International along with Kautsky and Plekhanov. Dadabhai Naoroji's works in the congress are praiseworthy. In 1886, 1893, and 1906, i.e., thrice was he elected as the president of INC. In 2014, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg inaugurated the Dadabhai Naoroji Awards for services to UK-India relations. India Post depicted Naoroji on stamps in 1963, 1997 and 2017. Contents 1Life and career 2Naoroji's drain theory and poverty 3Views and legacy 4Works Life and career Naoroji was born in Navsari into a Gujarati-speaking Parsi family, and educated at the Elphinstone Institute School.[7] He was patronised by the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad III, and started his career life as Dewan (Minister) to the Maharaja in 1874. Being an Athornan (ordained priest), Naoroji founded the Rahnumai Mazdayasan Sabha (Guides on the Mazdayasne Path) on 1 August 1851 to restore the Zoroastrian religion to its original purity and simplicity. -

Distribution of Publications to Schools and Colleges English Hindi

[English] 11. C.W.M.G. - Vol. 44 (rep) 12. Gandhi - A Pictorial Biography (rep) Distribution of Publications to Schools and Colleges 13. C.W.M.C. Vol. XIII (rep) 14. C.W.M.C. Vol. LXXXIV (rep) 960. SHRI HARIN PATHAK : Will the Minister of INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING be pleased to 15. Gandhi - Ordained in South Africa state : 16. Ancient India (rep) (a) the names of publications brought out by his 17. Challenge to the Empire - (rep) Ministry during the year 1995*96 and 1996-97; A Study of Netaji (b) the steps taken to ensure their proper 18. Sardar Patel Memorial distribution; Lectures 1993-94 (c) whether these publications are also being 19. Folk Tales of Kerala supplied to schools and colleges; 20. C.W.M.C. Vol. XII (rep) (d) if not, the reasons therefor; and 21. Mass Media in India 1994-95 (e) the steps taken to ensure their supply to schools and colleges? 22. The years of Endeavour : (rep) Selected Speeches of THE MINISTER OF CIVIL AVIATION AND MINISTER Indira Gandhi. OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING (SHRI C.M. IBRAHIM) : (a) and (b) The lists of priced publications 23. Indian Tribes through the Ages (rep) brought out by the Publication Division are given in the 24. P.V. Narasimha Rao’s Selected enclosed Statement. The publications are sold through Speeches - Vol. IV a network of Sales Emporia owned by the Publications 25. An Outline History of Indian People (rep) Division and a number of agents/booksellers spread all over the country. 26. C.W.M.C. -

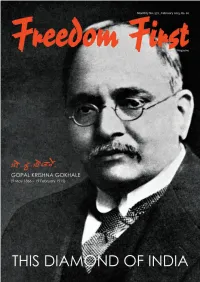

Gokhale and Gandhi - Their Second Meeting Birth Centenary Lectures Which Were Later Published Under Prabha Ravi Shankar 14 the Title Gokhale and Modern India

NEW PUBLICATIONS For a brief description of these publications turn to page 34. For copies, get in touch with us at Freedom First, 3rd floor, Army and Navy Building, 148 Mahatma Gandhi Road, Mumbai 4000001. You can also email us at [email protected] or phone us at 022-22843416 or 022-66396366. 2 Freedom First February 2015 www.freedomfirst.in Freedom First The Liberal Magazine – 63rd Year of Publication Between Ourselves No.572 February 2015 GOPAL KRISHNA GOKHALE Contents 1866 - 1915 New Publications 2 Gopal Krishna Gokhale was the founder of the Servants Between Ourselves 3 of India Society, President of the Indian National Congress The Legacy of Gopal Krishna Gokhale and a member of the Imperial Legislative Council. His Death Centenary Year, February 19, 1915-2014, was commemorated Introduction by several organisations. Among them the Deccan A. B. Shah 4 Education Society, Servants of India Society, Gokhale Laying the Foundation for a Modern India Institute of Politics and Economics, Indian Committee for S. P. Aiyar 4 Cultural Freedom, Project for Economic, Indian Secular His Relevance Today Society and Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya. Aroon Tikekar 8 His Achievements On his birth centenary in May 1966, the Indian Committee Sunil Gokhale 11 for Cultural Freedom (ICCF) had organised a series of three Gokhale and Gandhi - Their Second Meeting Birth Centenary Lectures which were later published under Prabha Ravi Shankar 14 the title Gokhale and Modern India. Sir Pherozeshah Mehta’s Tribute Godrej N. Dotivala 16 Forty eight years on, on November 15, 2014, the ICCF, in Some Contemporaries of Gokhale in Poona association with the Project for Economic Education, the R. -

Dr Ghulam Shabir (6)

Growth and Development of the Muslim Press in the Sub-Continent Dr.Ghulam Shabir* Baber Khakan ** Abstract: History of the journalism in the Sub-continent (Indo-Pak) goes back to the 11th century with Waqa-I-Navees (Newsmen) during the regime of Mahmood Ghaznavi. Waqa-I-Navees were appointed to keep the government well informed about all important happenings. Though, Sultans of Delhi were the first to establish the system on sound basis, yet it were the Mughals, who really worked hard to make it flourish. In the 19th century the Hindus were more advanced than the Muslims in almost every sphere of life. In the field of Journalism Hindus dominated the Indian press and propagated their cause. On the other hand the Muslims remained only followers to establish their press. Some Muslim Newspapers were pro Hindu. Thus there were a few Muslim newspapers that really represented the Indian Muslim’s point of view. This paper will examine the efforts of the Muslims to establish their own Urdu / English press. Modern Journalism started in the Sub-continent in early 19th century. First English newspaper in the Sub-continent was HICKEY BENGAL GAZETTE, which appeared in 1780 under the editorship of James Augustus Hickey-In 1818, James Silk followed Hickey, (1786-1855), who started publishing Calcutta journal. However its publication was ceased in 1823. (1) English did not become the court language till 1837. Muslims were generally against the adoption of this foreign language. This situation further violated their interest in the field of modern journalism, which was evident during the early period of the 19th century. -

Letter for Savannah Vyoral

HIS 3315-500: MODERN SOUTH ASIA SPRING 2021 Aryendra Chakravartty Contact Information Department of History E-mail: [email protected] Liberal Arts North 355 Office Hours: Online office hours: Monday: 1-4 pm Tuesday: 9-11 am Available by email and zoom COURSE DESCRIPTION Home to over 1.5 billion people, South Asia is a land of enormous diversity and extreme contrasts. Often represented as an exotic land with deeply embedded tradition and culture, it also produces nearly half of the world’s software. It is a place where the old and new, the modern and traditional, urban and rural, and the rich and poor jostle together for space. The primary aim of this course is to provide historical depth and comparative perspective on South Asia’s transition to social, economic and political “modernity” through its experience of British colonial rule, its struggle for independent nationhood and its experiments with democracy as independent nations. As such, the course will provide historical depth and comparative perspective on this sub- continent and elucidate on the experiment that is modern South Asia. We will survey the history of the subcontinent from the decline of the Mughal empire in 1707 to the establishment of British rule from 1757, to the rise of anti-colonial nationalisms in the 19th and 20th centuries culminating in independence and partition in 1947, and finally, to the 1950’s post-independent India. In the process we will also engage with these fundamental questions. How were the British able to establish their rule in the subcontinent? What was the impact of colonial rule? How did varying populations in India respond to colonial rule? How did anti-colonial nationalism evolve in the subcontinent? Why did M. -

Political and National Life and Affairs

Political and National Life and Affairs Volume I By: M.K. Gandhi Compiled and Edited by: V.B. Kher First Published: September 1967 Printed and Published by: Jitendra T. Desai Navajivan Mudranalaya, Ahmedabad 380014 (India) Political and National Life and Affairs INTRODUCTION In a recent publication1 Mr. Sasadhar Sinha has blamed Mahatma Gandhi for the partition of India and has alleged that he was "a dismal political failure". According to him, "religion and politics are basically incompatible disciplines"; Gandhiji approached politics from the point of view of religion; he scared the Muslims and led them to conclude that in a Free India they would be reduced to the position of second class citizens. This naturally drove them to insist on the partition of the country. The indictment of Gandhiji by the author raises the following questions: 1. Are religion and politics incompatible disciplines? 2. Did Gandhiji approach politics from the point of view of religion? 3. Was Gandhiji's approach to politics responsible for the partition of India? 4. Was Gandhiji a dismal political failure as alleged? It cannot be gainsaid that Gandhiji did approach politics from an ethical and a humanitarian point of view but this outlook must be distinguished from a denominational religious outlook. But was he the original author of this approach in Indian politics? That must, first of all, be examined. The remaining questions also cannot be answered without a critical study of the recent Indian history. I would clarify here that it is not my intention to give a detailed analysis of the genesis of Pakistan except insofar as it is, relevant to the theme of the present work. -

MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 to the PRESENT): HIS2CO1 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT - FIRST PHASE (1885- 1917) (2014 Admission Onwards)

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION COMPLEMENTARY COURSE MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 TO THE PRESENT): HIS2CO1 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT - FIRST PHASE (1885- 1917) (2014 Admission onwards) Multiple Choice Questions Prepared by Dr.N.PADMANABHAN Associate Professor&Head P.G.Department of History C.A.S.College, Madayi P.O.Payangadi-RS-670358 Dt.Kannur-Kerala. 1. The Sepoy Mutiny broke out in ……………….. a)1847 b)1857 c)1869 d)1887 2. Indian National Congress was formed in ………………… a)1875 b)1885 c)1875 d)1895 3. Zamindari Association was launched in …………….in March 1838. a) Madras b) Calcutta c) Bombay d) Kashmir 4. Bengal British India Society founded in Calcutta on 20 April……………….. a) 1843 b) 1848 c) 1853 d) 1857 1 5. In 1828 ……………founded with his students the 'Academic Association' which organized debates on various subjects. a) Derozio b) George Thompson c) Voltaire d) Hume 6. British Indian Association was founded on October 29, 1851 at ……………with Raja radhakanta dev and debendranath Tagore as its President and Secretary respectively. a) Calcutta b) Bombay c) Ahmadabad d) Pondicherry 7. The East India Association was founded by …………….in 1866, in collaboration with Indians and retired British officials in London. a) Dadabhai Naoroji b) Ramgopal Ghosh c) Peary chand mitra d)Krishnadas Pal. 8. The first organisation in the Madras Presidency to agitate for the rights of Indians was the Madras Native Association which was established by publicist …………………in 1849. a) Pearychand Mitra b) Tarachand Chakravarty c) Gazulu Lakshminarasu Chetty d)Ramtanu Lahiri. 9. In May…………….., S. Ramaswami Mudaliar and P.