Avian Seasonality at a Locality in the Central Paraguayan Chaco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity and Structure of Bird and Mammal Communities in the Semiarid Chaco Region: Response to Agricultural Practices and Landscape Alterations

Diversity and structure of bird and mammal communities in the Semiarid Chaco Region: response to agricultural practices and landscape alterations Julieta Decarre March 2015 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Division of Ecology and Evolution, Department of Life Sciences Imperial College London 2 Imperial College London Department of Life Sciences Diversity and structure of bird and mammal communities in the Semiarid Chaco Region: response to agricultural practices and landscape alterations Supervised by Dr. Chris Carbone Dr. Cristina Banks-Leite Dr. Marcus Rowcliffe Imperial College London Institute of Zoology Zoological Society of London 3 Declaration of Originality I herewith certify that the work presented in this thesis is my own and all else is referenced appropriately. I have used the first-person plural in recognition of my supervisors’ contribution. People who provided less formal advice are named in the acknowledgments. Julieta Decarre 4 Copyright Declaration The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives licence. Researchers are free to copy, distribute or transmit the thesis on the condition that they attribute it, that they do not use it for commercial purposes and that they do not alter, transform or build upon it. For any reuse or redistribution, researchers must make clear to others the licence terms of this work 5 “ …and we wandered for about four hours across the dense forest…Along the path I could see several footprints of wild animals, peccaries, giant anteaters, lions, and the footprint of a tiger, that is the first one I saw.” - Emilio Budin, 19061 I dedicate this thesis To my mother and my father to Virginia, Juan Martin and Alejandro, for being there through space and time 1 Book: “Viajes de Emilio Budin: La Expedición al Chaco, 1906-1907”. -

Northwest Argentina (Custom Tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour Leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-Guided by Sam Woods

Northwest Argentina (custom tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-guided by Sam Woods Trip Report by Andrés Vásquez; most photos by Sam Woods, a few by Andrés V. Elegant Crested-Tinamou at Los Cardones NP near Cachi; photo by Sam Woods Introduction: Northwest Argentina is an incredible place and a wonderful birding destination. It is one of those locations you feel like you are crossing through Wonderland when you drive along some of the most beautiful landscapes in South America adorned by dramatic rock formations and deep-blue lakes. So you want to stop every few kilometers to take pictures and when you look at those shots in your camera you know it will never capture the incredible landscape and the breathtaking feeling that you had during that moment. Then you realize it will be impossible to explain to your relatives once at home how sensational the trip was, so you breathe deeply and just enjoy the moment without caring about any other thing in life. This trip combines a large amount of quite contrasting environments and ecosystems, from the lush humid Yungas cloud forest to dry high Altiplano and Puna, stopping at various lakes and wetlands on various altitudes and ending on the drier upper Chaco forest. Tropical Birding Tours Northwest Argentina, Nov.2015 p.1 Sam recording memories near Tres Cruces, Jujuy; photo by Andrés V. All this is combined with some very special birds, several endemic to Argentina and many restricted to the high Andes of central South America. Highlights for this trip included Red-throated -

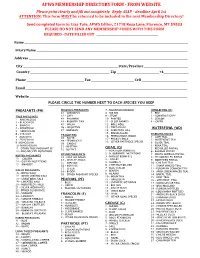

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - from WEBSITE Please Print Clearly and Fill out Completely

APWS MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY FORM - FROM WEBSITE Please print clearly and fill out completely. Reply ASAP – deadline April 1st ATTENTION: This form MUST be returned to be included in the next Membership Directory! Send completed form to: Lisa Tate, APWS Editor, 21718 Kesa Lane, Florence, MT 59833 PLEASE DO NOT SEND ANY MEMBERSHIP FUNDS WITH THIS FORM REQUIRED - DATE FILLED OUT ______________________________________________ Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Aviary Name __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ City ________________________________________________________________________ State/Province _________________________________ Country ___________________________________________________________ Zip ________________________________+4___________________ Phone ___________________________________________ Fax ________________________________ Cell __________________________________ Email _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Website ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PLEASE CIRCLE THE NUMBER NEXT TO EACH SPECIES YOU KEEP PHEASANTS (PH) PEACOCK-PHEASANTS 7 - MOUNTAIN BAMBOO JUNGLEFOWL -

Aves: Cuculidae)

Bol. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. Parag. Vol. 19, nº 2 (Dic. 2015): 58-61100-100 OBSERVATIONS OF NOVEL FEEDING TACTICS IN GUIRA CUCKOO GUIRA GUIRA (AVES: CUCULIDAE) P. Smith1,2 1Fauna Paraguay, Encarnación, Itapúa, Paraguay. www.faunaparaguay.com. E-mail: [email protected] 2Para La Tierra, Reserva Natural Laguna Blanca, San Pedro, Paraguay. Abstract.- Two unusual feeding observations by Guira Cuckoo Guira guira (Cuculidae) are reported. The birds were seen to raid the closed nests of the butterfly Brassolis sophorae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), and also to take cicadas (Auchenorrhyncha) that had become trapped in a mist-net. Key words: Auchenorrhyncha, Brassolis sophorae, foraging, Nymphalidae, Paraguay. Resumen.- Se reportan dos observaciones de comportamiento de forrajeo poco usual para la Piririta Guira guira (Cu- culidae). Las aves fueron observados saqueando los nidos cerrados de la mariposa Brassolis sophorae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), y tambien a depredar chicharras (Auchenorrhyncha) que habían quedado atrapados en redes de niebla. Palabras clave: Auchenorrhyncha, Brassolis sophorae, forrageo, Nymphalidae, Paraguay. The Guira Cuckoo Guira guira (Gmelin, 1798) valho et al., 1998). The social larvae (Fig. 1) is a widespread socially-breeding cuculid feed nocturnally on palms (Arecaceae) and are (Macedo, 1992, 1994; Macedo & Bianchi, 1997) considered agricultural pests because of their found throughout eastern South America from tendency to completely defoliate the plants upon northeastern Brazil to south-central Argentina which they feed (Cleare, 1915; Rai, 1971). The (Payne, 2005). In Paraguay it is a common and larvae take refuge by day in large communal familiar species, occurring in open areas in silk nests, interwoven within the palm leaves small, noisy flocks of 6 to 8, or exceptionally (Marassá, 1985), and mark their trail with a silk up to 20 birds (Payne, 2005). -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

Distributional Notes on the Birds of Peru, Including Twelve Species Previously Unreported from the Republic

Number 37 26 March 1969 OCCASIONAL PAPERS OF THE MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY Baton Rouge, Louisiana DISTRIBUTIONAL NOTES ON THE BIRDS OF PERU, INCLUDING TWELVE SPECIES PREVIOUSLY UNREPORTED FROM THE REPUBLIC By John P. O’Neill During eight years of participation in Louisiana State University Peruvian expeditions my field companions and I have collected a number of specimens that represent extensions of known range for the species involved. Two of the specimens here reported are in the American Museum of Natural History in New York. All the others were collected by personnel of the Louisiana State University Museum of Zoology and deposited in that museum. Sub specific determinations have been made with the use of comparative material at these two institutions. Extensions of range represent departures from previously known status as given by Meyer de Schauensee (1966). Most of the specimens here reported came from two localities: (1) Balta, a Cashinahua Indian village on the Río Curanja (at the point where the streams known to the local Cashinahuas as the Xumuya and the Inuya enter the Río Curanja, lat. 10°08' S, long. 71°13' W, elevation ca. 300 m), Depto. Loreto; (2) Yarinacocha, an oxbow lake about 15 km by road NNW of Pucallpa, Depto. Loreto. Other localities are identified in the accounts of the species under discussion. Dean Amadon of the American Museum of Natural History kindly per mitted me the use of collections in his care. Charles E. O’Brien of the same institution and Rodolphe Meyer de Schauensee of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia supplied information pertaining to the status of certain species in Peru. -

Brood Parasitism in a Host Generalist, the Shiny Cowbird: I

BROOD PARASITISM IN A HOST GENERALIST, THE SHINY COWBIRD: I. THE QUALITY OF DIFFERENT SPECIES AS HOSTS PAUL MASON 1 Departmentof Zoology,University of Texas,Austin, Texas 78712 USA ASSTRACT.--TheShiny Cowbird (Molothrusbonariensis) of South America, Panama, and the West Indies is an obligate brood parasiteknown to have used 176 speciesof birds as hosts. This study documentswide variability in the quality of real and potential hostsin terms of responseto eggs, nestling diet, and nest survivorship. The eggs of the parasiteare either spotted or immaculate in eastern Argentina and neighboring parts of Uruguay and Brazil. Most speciesaccept both morphs of cowbird eggs,two reject both morphs, and one (Chalk- browed Mockingbird, Mimus saturninus)rejects immaculate eggs but acceptsspotted ones. No species,via its rejection behavior, protectsthe Shiny Cowbird from competition with a potentialcompetitor, the sympatricScreaming Cowbird (M. rufoaxillaris).Cross-fostering ex- periments and natural-history observationsindicate that nestling cowbirds require a diet composedof animal protein. Becausemost passerinesprovide their nestlingswith suchfood, host selectionis little restricted by diet. Species-specificnest survivorship, adjustedto ap- propriatevalues of Shiny Cowbird life-history variables,varied by over an order of mag- nitude. Shiny Cowbirds peck host eggs.This density-dependentsource of mortality lowers the survivorshipof nestsof preferred hostsand createsnatural selectionfor greater gener- alization. Host quality is sensitive to the natural-history attributes of each host speciesand to the behavior of cowbirds at nests.Received 4 June1984, accepted26 June1985. VARIATIONin resourcequality can have great parasitized176 species(Friedmann et al. 1977). ecologicaland evolutionary consequences.Ob- The Shiny Cowbird is sympatric with a poten- ligate brood parasites never build nests but tial competitor, the ScreamingCowbird (M. -

Brazil: the Pantanal and Amazon, July 2015

Tropical Birding Trip Report Brazil: The Pantanal and Amazon, July 2015 BRAZIL: The Pantanal and Amazon 1-15 July 2015 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos, except for the Blue Finch, by Nick Athanas. Thanks to Mark Gawn for sharing his Blue Finch photo Bare-eyed Antbird was one of many highlights from this fun trip From the unparalleled biodiversity of the primeval Amazonian forest to the amazing abundance of wildlife in the Pantanal, this tour is always fascinating and great fun, and the superb lodges and tasty food make it especially enjoyable. This year was wetter than normal and we even got soaked once in the Pantanal, which is almost unheard of in July; the extra water definitely helped the overall bird numbers, so I certainly was not complaining, and it was still pretty darn dry compared to most South American tours. When I asked the group at the end of the trip for favorite sightings, everyone mentioned something totally different. There were so many memorable sightings that trying to pick one, or even a few, was almost futile. Some that were mentioned, in no real order, included: superb close-ups of Bare-eyed Antbirds at an antswarm at Cristalino (photo above); the “ginormous” Yellow Anaconda we saw crossing the Transpantanal Highway on our last full day, the minute and fabulous Horned Sungem from the Chapada, a superb encounter with the rare White-browed Hawk from one of the towers at Cristalino, our very successful hunt for the newly-described Alta Floresta Antpitta, and last but far from least, the magnificent Jaguar we saw for an extended period of time along the banks of the Três Irmãos River. -

Guia Para Observação Das Aves Do Parque Nacional De Brasília

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234145690 Guia para observação das aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília Book · January 2011 CITATIONS READS 0 629 4 authors, including: Mieko Kanegae Fernando Lima Favaro Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Bi… 7 PUBLICATIONS 74 CITATIONS 17 PUBLICATIONS 69 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Fernando Lima Favaro on 28 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Brasília - 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA Aílton C. de Oliveira Mieko Ferreira Kanegae Marina Faria do Amaral Fernando de Lima Favaro Fotografia de Aves Marcelo Pontes Monteiro Nélio dos Santos Paulo André Lima Borges Brasília, 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO APRESENTAÇÃO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA É com grande satisfação que apresento o Guia para Observação REPÚblica FEDERATiva DO BRASIL das Aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília, o qual representa um importante instrumento auxiliar para os observadores de aves que frequentam ou que Presidente frequentarão o Parque, para fins de lazer (birdwatching), pesquisas científicas, Dilma Roussef treinamentos ou em atividades de educação ambiental. Este é mais um resultado do trabalho do Centro Nacional de Pesquisa e Vice-Presidente Conservação de Aves Silvestres - CEMAVE, unidade descentralizada do Instituto Michel Temer Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) e vinculada à Diretoria de Conservação da Biodiversidade. O Centro tem como missão Ministério do Meio Ambiente - MMA subsidiar a conservação das aves brasileiras e dos ambientes dos quais elas Izabella Mônica Vieira Teixeira dependem. -

A Comprehensive Species-Level Molecular Phylogeny of the New World

YMPEV 4758 No. of Pages 19, Model 5G 2 December 2013 Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution xxx (2013) xxx–xxx 1 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev 5 6 3 A comprehensive species-level molecular phylogeny of the New World 4 blackbirds (Icteridae) a,⇑ a a b c d 7 Q1 Alexis F.L.A. Powell , F. Keith Barker , Scott M. Lanyon , Kevin J. Burns , John Klicka , Irby J. Lovette 8 a Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, and Bell Museum of Natural History, University of Minnesota, 100 Ecology Building, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 9 55108, USA 10 b Department of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182, USA 11 c Barrick Museum of Natural History, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, USA 12 d Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14950, USA 1314 15 article info abstract 3117 18 Article history: The New World blackbirds (Icteridae) are among the best known songbirds, serving as a model clade in 32 19 Received 5 June 2013 comparative studies of morphological, ecological, and behavioral trait evolution. Despite wide interest in 33 20 Revised 11 November 2013 the group, as yet no analysis of blackbird relationships has achieved comprehensive species-level sam- 34 21 Accepted 18 November 2013 pling or found robust support for most intergeneric relationships. Using mitochondrial gene sequences 35 22 Available online xxxx from all 108 currently recognized species and six additional distinct lineages, together with strategic 36 sampling of four nuclear loci and whole mitochondrial genomes, we were able to resolve most relation- 37 23 Keywords: ships with high confidence. -

Diversity of Mammals and Birds Recorded with Camera-Traps in the Paraguayan Humid Chaco

Bol. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. Parag. Vol. 24, nº 1 (Jul. 2020): 5-14100-100 Diversity of mammals and birds recorded with camera-traps in the Paraguayan Humid Chaco Diversidad de mamíferos y aves registrados con cámaras trampa en el Chaco Húmedo Paraguayo Andrea Caballero-Gini1,2,4, Diego Bueno-Villafañe1,2, Rafaela Laino1 & Karim Musálem1,3 1 Fundación Manuel Gondra, San José 365, Asunción, Paraguay. 2 Instituto de Investigación Biológica del Paraguay, Del Escudo 1607, Asunción, Paraguay. 3 WWF. Bernardino Caballero 191, Asunción, Paraguay. 4Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract.- Despite its vast extension and the rich fauna that it hosts, the Paraguayan Humid Chaco is one of the least studied ecoregions in the country. In this study, we provide a list of birds and medium-sized and large mammals recorded with camera traps in Estancia Playada, a private property located south of Occidental region in the Humid Chaco ecoregion of Paraguay. The survey was carried out from November 2016 to April 2017 with a total effort of 485 camera-days. We recorded 15 mammal and 20 bird species, among them the bare-faced curassow (Crax fasciolata), the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), and the neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis); species that are globally threatened in different dregrees. Our results suggest that Estancia Playada is a site with the potential for the conservation of birds and mammals in the Humid Chaco of Paraguay. Keywords: Species inventory, Mammals, Birds, Cerrito, Presidente Hayes. Resumen.- A pesar de su vasta extensión y la rica fauna que alberga, el Chaco Húmedo es una de las ecorregiones menos estudiadas en el país. -

21 Sep 2018 Lists of Victims and Hosts of the Parasitic

version: 21 Sep 2018 Lists of victims and hosts of the parasitic cowbirds (Molothrus). Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum Brood parasitism is an awkward term to describe an interaction between two species in which, as in predator-prey relationships, one species gains at the expense of the other. Brood parasites "prey" upon parental care. Victimized species usually have reduced breeding success, partly because of the additional cost of caring for alien eggs and young, and partly because of the behavior of brood parasites (both adults and young) which may directly and adversely affect the survival of the victim's own eggs or young. About 1% of all bird species, among 7 families, are brood parasites. The 5 species of brood parasitic “cowbirds” are currently all treated as members of the genus Molothrus. Host selection is an active process. Not all species co-occurring with brood parasites are equally likely to be selected nor are they of equal quality as hosts. Rather, to varying degrees, brood parasites are specialized for certain categories of hosts. Brood parasites may rely on a single host species to rear their young or may distribute their eggs among many species, seemingly without regard to any characteristics of potential hosts. Lists of species are not the best means to describe interactions between a brood parasitic species and its hosts. Such lists do not necessarily reflect the taxonomy used by the brood parasites themselves nor do they accurately reflect the complex interactions within bird communities (see Ortega 1998: 183-184). Host lists do, however, offer some insight into the process of host selection and do emphasize the wide variety of features than can impact on host selection.