The Construction of National Identity in Poland's Newspapers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth As a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity*

Chapter 8 The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity* Satoshi Koyama Introduction The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) was one of the largest states in early modern Europe. In the second half of the sixteenth century, after the union of Lublin (1569), the Polish-Lithuanian state covered an area of 815,000 square kilometres. It attained its greatest extent (990,000 square kilometres) in the first half of the seventeenth century. On the European continent there were only two larger countries than Poland-Lithuania: the Grand Duchy of Moscow (c.5,400,000 square kilometres) and the European territories of the Ottoman Empire (840,000 square kilometres). Therefore the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the largest country in Latin-Christian Europe in the early modern period (Wyczański 1973: 17–8). In this paper I discuss the internal diversity of the Commonwealth in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and consider how such a huge territorial complex was politically organised and integrated. * This paper is a part of the results of the research which is grant-aided by the ‘Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research’ program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science in 2005–2007. - 137 - SATOSHI KOYAMA 1. The Internal Diversity of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Poland-Lithuania before the union of Lublin was a typical example of a composite monarchy in early modern Europe. ‘Composite state’ is the term used by H. G. Koenigsberger, who argued that most states in early modern Europe had been ‘composite states, including more than one country under the sovereignty of one ruler’ (Koenigsberger, 1978: 202). -

Wojciech Roszkowski Post-Communist Lustration in Poland: a Political and Moral Dilemma Congress of the Societas Ethica, Warsaw 22 August 2009 Draft Not to Be Quoted

Wojciech Roszkowski Post-Communist Lustration in Poland: a Political and Moral Dilemma Congress of the Societas Ethica, Warsaw 22 August 2009 Draft not to be quoted 1. Introduction Quite recently a well-known Polish writer stated that the major dividing line in the Polish society runs across the attitude towards lustration. Some Poles, he said, have been secret security agents or collaborators or, for some reasons, defend this cooperation, others have not and want to make things clear1. Even if this statement is a bit exaggerated, it shows how heated the debates on lustration in Poland are. Secret services in democratic countries are a different story than security services in totalitarian states. Timothy Garton Ash even calls this comparison “absurd”2. A democratic state is, by definition, a common good of its citizens. Some of them are professionals dealing with the protection of state in police, armed forces and special services, all of them being subordinated to civilian, constitutional organs of the state. Other citizens are recruited by these services extremely rarely and not without their consent. In totalitarian states secret services are the backbone of despotic power of the ruling party and serve not the security of a country but the security of the ruling elites. Therefore they should rather be given the name of security services. They tend to bring under their control all aspects of political, social, economic, and cultural life of the subjects of the totalitarian state, becoming, along with uniformed police and armed forces, a pillar of state coercion. Apart from propaganda, which is to make people believe in the ideological goals of the totalitarian state, terror is the main vehicle of power, aiming at discouraging people from any thoughts and deeds contrary to the said goals and even from any activity independent of the party-state. -

No. 23 TRONDHEIM STUDIES on EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES

No. 23 TRONDHEIM STUDIES ON EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES & SOCIETIES Barbara Törnquist-Plewa & Agnes Malmgren HOMOPHOBIA AND NATIONALISM IN POLAND The reactions to the march against homophobia in Cracow 2004 December 2007 Barbara Törnquist-Plewa is Professor of Eastern and Central European Studies at Lund University, Sweden, where she is also the director of the Centre for European Studies. Her publications include a large number of articles and book chapters as well as The Wheel of Polish Fortune, Myths in Polish Collective Consciousness during the First Years of Solidarity (Lund 1992) and Vitryssland - Språk och nationalism i ett kulturellt gränsland (Lund 2001). She has edited a number of books, the latest being History, Language and Society in the Borderlands of Europe. Ukraine and Belarus in Focus (2006) and Skandinavien och Polen – möten, relationer och ömsesidig påverkan (2007). Agnes Malmgren is a freelance writer, with a BA in Eastern and Central European Studies from Lund University. In 2007 she received the award of the Polish Institute in Stockholm for the best reportage about Poland. She has been coordinator of the annual festival “Culture for Tolerance” in Krakow several times and has also been involved in other kinds of gay and lesbian activism in Poland and Sweden. © 2007 Barbara Törnquist-Plewa & Agnes Malmgren and the Program on East European Cultures and Societies, a program of the Faculties of Arts and Social Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Translated by Margareta Faust. Edited by Sabrina P. Ramet. ISSN 1501-6684 Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies Editors: György Péteri and Sabrina P. -

The Piast Horseman)

Coins issued in 2006 Coins issued in 2006 National Bank of Poland Below the eagle, on the right, an inscription: 10 Z¸, on the left, images of two spearheads on poles. Under the Eagle’s left leg, m the mint’s mark –– w . CoinsCoins Reverse: In the centre, a stylised image of an armoured mounted sergeant with a bared sword. In the background, the shadow of an armoured mounted sergeant holding a spear. On the top right, a diagonal inscription: JEèDZIEC PIASTOWSKI face value 200 z∏ (the Piast Horseman). The Piast Horseman metal 900/1000Au finish proof – History of the Polish Cavalry – diameter 27.00 mm weight 15.50 g mintage 10,000 pcs Obverse: On the left, an image of the Eagle established as the state Emblem of the Republic of Poland. On the right, an image of Szczerbiec (lit. notched sword), the sword that was traditionally used in the coronation ceremony of Polish kings. In the background, a motive from the sword’s hilt. On the right, face value 2 z∏ the notation of the year of issue: 2006. On the top right, a semicircular inscription: RZECZPOSPOLITA POLSKA (the metal CuAl5Zn5Sn1 alloy Republic of Poland). At the bottom, an inscription: 200 Z¸. finish standard m Under the Eagle’s left leg, the mint’s mark:––w . diameter 27.00 mm Reverse: In the centre, a stylised image of an armoured weight 8.15 g mounted sergeant with a bared sword. In the background, the mintage 1,000,000 pcs sergeant’s shadow. On the left, a semicircular inscription: JEèDZIEC PIASTOWSKI (the Piast Horseman). -

Poland Is a Democratic State Ruled by Law, Whose System Rests on the Principle of the Separation and Balance of Powers

SOCIAL SCIENCES COLLECTION GUIDES OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS www.bl.uk/subjects/national-and-international-government-publications Polish government documents INTRODUCTION What follows is a selection only of the main categories of material. Always check the catalogues - for some of the titles mentioned, we have incomplete holdings. Some other British Library holdings of Polish government materials are recorded in Explore the British Library, our main catalogue [http://explore.bl.uk/]. However other material has to be traced through a range of manual records and published indexes. If you do not find what you are looking for in Explore the British Library, please contact the Enquiry Desk in the Social Sciences Reading Room, where expert staff will check further on your behalf. CONTENTS 1. PARLIAMENTARY PUBLICATIONS ............................................................... 2 1.1 Parliamentary publications ....................................................................... 2 1.2 Parliamentary papers ............................................................................... 3 2. CONSTITUTION ........................................................................................... 4 3. LEGISLATION AND COURT REPORTS .......................................................... 5 3.2 Court Reports ......................................................................................... 7 3.3 Constitutional Tribunal ............................................................................ 8 4. DEPARTMENTAL PUBLICATIONS ................................................................ -

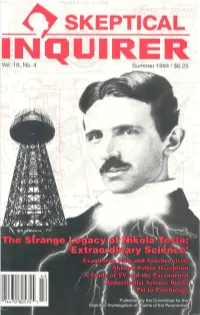

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

The October 2015 Polish Parliamentary Election

An anti-establishment backlash that shook up the party system? The october 2015 Polish parliamentary election Article (Accepted Version) Szczerbiak, Aleks (2016) An anti-establishment backlash that shook up the party system? The october 2015 Polish parliamentary election. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 18 (4). pp. 404-427. ISSN 1570-5854 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/63809/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk An anti-establishment backlash that shook up the party system? The October 2015 Polish parliamentary election Abstract The October 2015 Polish parliamentary election saw the stunning victory of the right-wing opposition Law and Justice party which became the first in post-communist Poland to secure an outright parliamentary majority, and equally comprehensive defeat of the incumbent centrist Civic Platform. -

Submitted To

POWER/KNOWLEDGE PRODUCTION A FOUCAULDIAN ANALYSIS OF DISCOURSES ON THE 2010 TU-154 CRASH IN SMOLENSK BY KAROLINA KUKLA SUBMITTED TO CENTRAL EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS SUPERVISORS: PROFESSOR VIOLETTA ZENTAI PROFESSOR PREM KUMAR RAJARAM CEU eTD Collection BUDAPEST, HUNGARY 2013 ABSTRACT This study analyze the Polish discourses on the 2010 Tu-154 plane crash in Smolensk in which 96 state officials, including the Polish president, were killed. Contrary to previous investigation on the aftermaths of the Smolensk plane crash which focused on the phenomenon of national mourning, my study examines the political and social division which the crash highlighted. With the use of a Foucauldian conceptual framework, this study investigates two major discourses on the crash: the national and liberal discourses. Whereas the former constituted the catastrophe as a result of an intentional action and produced theories of conspiracy and the responsibility of Russia for the crash, the latter established the crash as a result of contingencies. It is argued that these explanations of the Smolensk plane crash depend on the relations specific to the rule-governed systems which incorporate various elements as institutions, events, theories or concepts. The major focus of this study is the process whereby one of these explanations, namely the accidental one, has been established as the official and true theory. A genealogical study of such events as appointments of experts committees, publications of the reports on the causes of the Smolensk plane crash, as well as struggles between the national and liberal discourses depicts the mechanism whereby the truth on Smolensk crash was constituted, and reveals the power relations which participated in this process. -

Minute of the 14Th EU-Russia PCC, 19-20

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT EU-RUSSIA PARLIAMENTARY COOPERATION COMMITTEE MINUTES FOURTEENTH MEETING Monday 19 September 2011, 14h30-18h30 and Tuesday 20 September 2011, 8h45-12h30 WARSAW, POLAND CONTENTS 1. Adoption of draft agenda (PE 467.621) 2. Adoption of Minutes of the 13th EU-Russia PCC Meeting on 15-16 December 2010 in Strasbourg (PE 467.623) 3. Two decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall - impacts for the region, the European Union and the Russian Federation Welcome speech by: - the Chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Sejm on behalf the Marshall of the Polish Sejm Introductory statements by: - the Co-Chairmen of the PCC - the Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs of Poland on behalf of the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy - the Russian Ambassador in Poland 4. Exchange of views on the special status of Kaliningrad region in the EU visa policy. 5. Follow-up of the works of WG1/2011 on Common neighbourhood issues and policies - exchange of views with Mr Schulz and Mr Klimov 6. Follow-up of the works of WG 2/2011 on Science and Research cooperation, rural development, and environmental protection - exchange of views with Mr Fleckenstein and Mr Gorbunov 1 PE 495.732 7. Follow-up of the works of WG 3/2011 on Sport, sport infrastructure and youth policies - exchange of views with Mr Peterle and Mr Klimov 8. Exchange of views on parliamentary election standards in the EU and in Russia in the presence of representatives of the OSCE/ODIHR Office in Warsaw and the Russian Central Electoral Committee 9. -

HISTORIA SCEPTYCYZMU Monografie Fundacji Na Rzecz Nauki Polskiej

HISTORIA SCEPTYCYZMU monografie fundacji na rzecz nauki polskiej rada wydawnicza prof. Tomasz Kizwalter, prof. Janusz Sławiński, prof. Antoni Ziemba, prof. Marek Ziółkowski, prof. Szymon Wróbel fundacja na rzecz nauki polskiej Renata Ziemińska HISTORIA SCEPTYCYZMU W POSZUKIWANIU SPÓJNOŚCI toruń 2013 Wydanie książki subwencjonowane przez Fundację na rzecz Nauki Polskiej w ramach programu Monografie FNP Redaktor tomu Anna Mądry Korekty Ewelina Gajewska Projekt okładki i obwoluty Barbara Kaczmarek Printed in Poland © Copyright by Renata Ziemińska and Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika Toruń 2013 ISBN 978-83-231-2949-3 WYDAWNICTWO NAUKOWE UNIWERSYTETU MIKOŁAJA KOPERNIKA Redakcja: ul. Gagarina 5, 87-100 Toruń tel. +48 56 611 42 95, fax +48 56 611 47 05 e-mail: [email protected] Dystrybucja: ul. Reja 25, 87-100 Toruń tel./fax: +48 56 611 42 38, e-mail: [email protected] www.wydawnictwoumk.pl Wydanie pierwsze Druk i oprawa: Abedik Sp. z o.o. ul. Glinki 84, 85-861 Bydgoszcz Spis treści wstęp ......................................................................................................... 9 część i. pojęcie i rodzaje sceptycyzmu rozdział 1. genealogia terminu „sceptycyzm” ........................... 15 rozdział 2. ewolucja pojęcia sceptycyzmu .................................. 21 Starożytny sceptycyzm jako zawieszenie sądów pretendujących do prawdy .......................................................................................... 21 Średniowieczny sceptycyzm jako uznanie słabości ludzkich sądów wobec Bożej wszechmocy -

The Crime of Genocide Committed Against the Poles by the USSR Before and During World War II: an International Legal Study, 45 Case W

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 45 | Issue 3 2012 The rC ime of Genocide Committed against the Poles by the USSR before and during World War II: An International Legal Study Karol Karski Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Karol Karski, The Crime of Genocide Committed against the Poles by the USSR before and during World War II: An International Legal Study, 45 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 703 (2013) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol45/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 45 Spring 2013 Issue 3 The Crime of Genocide Committed Against the Poles by the USSR Before and During WWII: An International Legal Study Karol Karski Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law·Vol. 45·2013 The Crime of Genocide Committed Against the Poles The Crime of Genocide Committed Against the Poles by the USSR Before and During World War II: An International Legal Study Karol Karski* The USSR’s genocidal activity against the Polish nation started before World War II. For instance, during the NKVD’s “Polish operation” of 1937 and 1938, the Communist regime exterminated about 85,000 Poles living at that time on the pre- war territory of the USSR. -

The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Consultation report The use and promotion of complementary and alternative medicine: making decisions about charitable status Introduction The Commission ran a public consultation on this subject between 13 March and 19 May 2017, as part of our review of how we decide whether organisations that use or promote complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies are charities. Our review is not about whether complementary and alternative therapies and medicines are ‘good’ or ‘bad’, but about what level of evidence the Commission should require when making assessments about an organisation’s charitable status. We would like to thank everyone who took the time to take part. This report sets out a summary of the responses received. The consultation We received over 670 written responses, far in excess of the number usually received for a Commission consultation. We also held two discussion events at our London office for organisations with a particular perspective on the issues under consideration. The majority of responses received were from individuals apparently writing in a personal capacity, but we also received over 100 submissions from people representing, or connected with, organisations with an interest in the consultation. The names of those organisations are set out in the annex to this report. The responses varied widely in length, detail and content. Given the welcome and exceptionally high level of engagement with the consultation, it has taken longer than initially anticipated to analyse the responses. However, we are grateful for the high level of engagement; the responses have helped further our understanding the breadth and complexity of the CAM sector.