Chapter 2: Plant Response to Elevated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mysore Cafe Menu Copy

mysorecafebh mysorecafebh 1 2 3 1. Banana Buns 0.500 7. Semige (Idiappam) Korma 0.700 2. Chow Chow Baath 0.600 8. Pundi 6 Pc(STEAMED RICE BALLS) 0.700 3. Upma Poha 0.600 9. Mysore Rasam Vada 0.600 4. Poori Srikhand 0.700 10. Idly Tovay (DAAL) 0.600 5. Poori Bhaji / Channa 0.700 11. Neer Dosa (5Pcs) 0.700 6. Poha and Banana 0.600 12. Davengere Benne Dosa 0.700 13. Kandha Poha 0.800 7 6 8 14. IDLI – 3 Pcs BD 0.600 Gently steamed rice and lentil puffs, served with Sambar and coconut chutney. 15-MEDU VADA 2Pcs BD 0.600 Delicious golden fried lentil doughnut fluffy in the middle and crispy on the outside. 15 14 16 17 16 .UPMA BD 0.500 Warm cream of wheat cooked with nuts, and served with coconut chutney. 17. Tomato Uttappam BD 0.900 18. Onion Chilly Uttappam BD 0.900 19. Uttappam Basket (3 types) BD 1.200 20. Tomato Omlette BD 0.900 21. Home Dosa (2Pcs) BD 0.800 Uttappams are made from lentils and rice fermented overnight, similar to the Dosa. They are cooked on both sides and come with a variety of toppings. Uthappams are the South Indian version of a Pizza. The people of Southern India have developed over the years the fine art of making the Dosa. The Dosa is a crepe made from a batter of soaked lentils and rice, ground together and fermented . All Dosas and Uthappams are accompanied with Sambar (lentil soup) and coconut chutney. -

Master File.Xlsx

AMOUNT OF UNCLAIMED AND UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2017-18 AS ON 31.03.2021 DUE DATE OF DEPOSIT TO Name of Shareholder ADD STATE PINCODE FOLIO NO. DP ID /CLIENT ID AMOUNT SHAREHOLDING IEPF 9-a,swati Building Amritkumbha Housing Society V G PHADKE B.s.road,dadar Bombay 400028 Maharashtra 400028 V762 552.00 9209-SEP-2025 VEENA MATHUR B/b 19/c Janakpuri New Delhi 110058 Delhi 110058 V817 552.00 92 09-SEP-2025 YOGESH KUMAR NANCHAND Revdi Bazar Cross Lane Ahmedabad 380002 Gujarat 380002 Y5062 5820.00 970 09-SEP-2025 001 Nalanda Apartments 24 Geetanjali Society VIKRAM S TALATI Chikuwadi,jetalpur Road Baroda 390005 Gujarat 390005 Z6007 162.00 2709-SEP-2025 3 Ambica Nagar Society B/h Ambar Cinema Kamana Road DINESH Visnagar N Guj 384315 Gujarat 384315 Z6086 1572.00 26209-SEP-2025 BECHARBHAI RAMABHAI MASANI At & Po Badarkha Ta Dholka Dist Ahmedabad 382270 Gujarat 382270 Z6105 720.00 120 09-SEP-2025 9 Jhulelal Society Jawahar Chowk Saramati Ahmedabad HASS M SADHNANI 380051 Gujarat 380051 Z6111 444.00 7409-SEP-2025 C/o Shivalal Oghadas Sheth Near Khamidana Gate Barvala HEENA SHETH Gheshah 382450 Gujarat 382450 Z6119 390.00 6509-SEP-2025 RAJESH S WADHWANI C/o Hotel Ellora Kranti Chowk Auranabad 431001 Maharashtra 431001 Z6120 780.00 130 09-SEP-2025 B 300 Pandurangashram 8th Main Malleswaram Bangalore SUNANDA SAVKOOR 566055 Karnataka 566055 Z6129 684.00 11409-SEP-2025 No 67 Veerappa Block 17th Cross Malleswaram Bangalore K VEERABHADRAPPA 560055 Karnataka 560055 Z6130 576.00 9609-SEP-2025 B N SHANTHAMURTHY47 30th Cross 7th Block Jayanagar -

Times.US PAGE 1 Times.US Globally Recognized Editor-In-Chief: Azeem A

APRIL 2018 www.Asia Times.US PAGE 1 www.Asia Times.US Globally Recognized Editor-in-Chief: Azeem A. Quadeer, M.S., P.E. APRIL 2018 Vol 9, Issue 4 Congratulations Shawkat Mohammed 90% of work-permits given to Shawkat Mohammed (Dallas) Achieved Prestigious Million Dollar Round Table ( Top of the Table ) membership H-1B visa-holders’ spouses are again this year. Indians Membership is Exclusive to World’s Leading 30 Mar 2018: 90% of work- The H-4 visa holders don’t were women, and the vast Financial Professionals. permits given to H-1B get a social security num- majority, 93%, were from visa-holders’ spouses are ber, and hence cannot be India, while 4% were from Indians employed. But they can get China.” Congratulations Shawkat Mohammed on achieving MDRT for the 6th time in a row! The United States has Your achievement is the greatest endorsement given work permits to over of your hard work and the trust your clients 71,000 spouses of H-1B visa holders, 90% of whom have put in you. are Indians. In 2015, the Obama government began issu- ing work authorization to spouses of H-1B visa holders. a driver’s license, pursue Spouses of H-1B visa hold- education and open bank Most likely yes: Will things ers who had been living account. change now that Donald in the US for six years, Trump is POTUS? and were in the process of In 2015, 80% of 1,25,000 applying for green cards, people who were issued Donald Trump in his were eligible for this pro- H-4 visas were Indians. -

Introduction Dadra & Nagar Haveli

Introduction Dadra & Nagar Haveli Located on the western side of the complexion with tribals (adivasi) foothills of western ghats constituting more than 75 percent encompassing an area of 491 square of the population, and the main km, the Union Territory (UT) of tribes are Dhodia, Kokna and Varli. Dadra & Nagar Haveli is the land The reserved forests comprise 40 of colourful tribals. Just 12 km percent of the UT providing a north west of Daman, a small part habitat for all kind of flora and of Gujarat (Vapi) separates the two. fauna. Because of proximity to the It has seen many rulers, ranging sea at Daman, the summer from the mighty Marathas to the temperature is not overpowering. fiery Portuguese. It was liberated The river Damanganga and in 1954 from Portuguese rule. its tributaries like the Varna, Dadra actually is much smaller Pipri and Sakartond criss cross the with only two villages apart from UT and drain into Arabian Sea Dadra itselt. Nagar Haveli consists at Daman. of 69 villages of which Silvassa, the The nearness of Daman, which is the capital of Dadra and Nagar Haveli sister UT, has common admini- is one. Dadra is separated from the stration with the Administrator as villages of Nagar Haveli by 3 km Head, has integrated the two UTs to of Gujarat territory. The entire form a composite block for the union territory is rural in its purpose of tourism. Visitors GUIDE Daman, Diu, Dadra & Nagar Haveli 1 CMYK The colourful dances and curious 200 and 20025' of latitude north rituals of this tribal land, top class and between the meridian 72050' resorts and complexes close to and 73015' of longitude. -

Feeding the City: Work and Food Culture of the Mumbai Dabbawalas

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/87 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. FEEDING THE CITY: WORK AND FOOD CULTURE OF THE MUMBAI DABBAWALAS Sara Roncaglia © Sara Roncaglia. This book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported Licence: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/ This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and commercial use, providing the work is not translated or altered and the following author and publisher attribution is clearly stated: Sara Roncaglia, Feeding the City: Work and Food Culture of the Mumbai Dabbawalas (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2013). As with all Open Book Publishers titles, digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254008 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-01-5 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-00-8 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-909254-02-2 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-03-9 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-04-6 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0031 Cover image: Preparation of a meal in Mumbai, May 2007. Photo by Sara Roncaglia. Translated from the Italian by Angela Arnone. Typesetting by www.bookgenie.in All paper used by Open Book Publishers is SFI (Sustainable Forestry Initiative), and PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Schemes) Certified. -

September 2015|| the Ruiaite

||September 2015|| the Ruiaite monthly Bulletin Editorial नमश्कार Ruiaite! Ushering in our second issue of the monthly bulletin this academic year, it gives us immense pleasure to take our readers on tour to experience the reections of our society. We attempt to bring ahead repercussions of various events, contributions of eminent personalities, aspects of individuals and the likes that go by unnoticed, through the Bulletin. Just as we celebrate the Teacher’s Day this month, the Ruiaite Bulletin Team wishes all Teachers a Happy Teachers Day’! Bearing in mind that, the essence of transmission of knowledge,values and ideas lie in the unending process of learning and teaching, we bring across expressions that render obedience to everyone and everything around us, that constantly impart on us the lessons of life. In this Edition we mark two new beginings. The column ‘KNOW YOUR RUIA’ is introduced, wherein the undiscovered facts and les of our college would reach out to all. The second being, a Comic Strip ‘TLO’, a satirical account of an observant Ruiaite. Every activity, idea or interaction amongst the Team is enriching. It was a pleasant surprise to see, many junior, new entrants in the team ll in big shoes as, they eciently essayed the commendable roles entrusted, at crucial stages of preparing the Bulletin. We take this opportu- nity to thank all our volunteers for their enthusiastic participation and involvement. We dedicate this Bulletin to our dear Volunteers. Bravo!! आभार !! The Ruiaite Team (L-R) Mr. Chetan Bandekar , Publisher of the Ruiaite Annual Magazine; Dr. Suhas Pednekar, Principal Ruia College; Mrs. -

Volume XII, Issue 1 | Price Rs. 3/-* April-June 2018

April-June 2018 Volume XII, Issue 1 | Price Rs. 3/-* Voice of GSB, July-Sep 2017, Page No. 1 www.gsbsabhamumbai.org / [email protected] Vol. XI, Issue 2 Dear Members : Please send your feedback and suggestions for your very own newsletter, Voice of GSB, by dropping in a mail to gsbsabha@ Namaskaru !! gmail.com. At the outset, I thank the Managing Committee for the Thank you. Happy Reading !!!!!! responsibility bestowed upon me as the President till the next Annual General Meeting. Stepping into the big shoes of our illustrious past Presidents is not an easy task but I assure you that In order to be of better service to our members, the Sabha I will do my very best with dedication and commitment. has subscribed to a bulk SMS service and will start send- ing updates about our activities / programmes by SMS to In January this year, we have embarked upon the task of repairs the members. and renovation of our iconic vastu, Sujir Gopal Nayak Memorial Kreeda Mandir. The building needed some urgent structural We request all our members to contact our Office Manager, repairs and so under the guidance of our Trustees, we decided to Shri Vishwanath Shenoy, on 022-2408 1499 (Mon. to Sat. 2 also do some work on the interiors renovation. We have appointed to 7 p.m.) and update your mobile number in our records. a Project Management Consultant to ensure that we have a value Kindly quote your membership number which you will proposition and that the quality of work is of the highest standards. -

Networks of Survival in Kinshasa, Mumbai, Detroit, and Comparison Cities; an Empirical Perspective

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Ph.D. Dissertations (Open Access) Salve's Dissertations and Theses 2-28-2018 Networks of Survival in Kinshasa, Mumbai, Detroit, and Comparison Cities; an Empirical Perspective Beryl S. Powell Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/phd_dissertations Part of the Economics Commons, History Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Powell, Beryl S., "Networks of Survival in Kinshasa, Mumbai, Detroit, and Comparison Cities; an Empirical Perspective" (2018). Ph.D. Dissertations (Open Access). 4. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/phd_dissertations/4 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ph.D. Dissertations (Open Access) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Salve Regina University Networks of Survival in Kinshasa, Mumbai, Detroit, and Comparison Cities; an Empirical Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the Humanities Program in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Beryl S. Powell Newport, Rhode Island February 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Beryl S. Powell All rights reserved ii To my father, John J. Slocum, 1914-1997, Who encouraged scholarship; And to my sons, Adam C. Powell IV and Sherman Scott Powell, From whom I learned more than I taught. And to the others . Appreciation also to Dr. Daniel Cowdin and Dr. Carolyn Fluehr Lobban, For their extensive assistance with this dissertation; and to Dr. Stephen Trainor, who enabled the final process. -

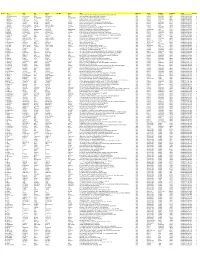

Shareholders Details Whose Shares Are Due for Transfer to IEPF.Xlsx

Sr. No. FN MN LN FH_FN FH_MN FH_LN ADD COUNTRY STATE DISTRICT PINCODE FLNO SHARES 1 AMBALAL NANSHA PATEL NANSHA PATEL 27 MADHAVBAUG SOCIETY OPP NIRNAYNAGAR CHANDLODIA ROAD AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT AHMEDABAD 382481 000000000000C9A00001 4 2 ANSUYAWDORASIKLAL SANKALCHAND MODY SANKALCHAND MODY TOPAS KHADKY SHETS POLE MANDVIS STREET AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT AHMEDABAD 380001 000000000000C9A00015 16 3 AMBALAL CHANDULAL PRAVINCHANDRA CHANDULAL PRAVINCHANDRA 7 COSMO VILLA NEAR PREMCHAND NAGAR AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT AHMEDABAD 380054 000000000000C9A00104 16 4 AMBALAL BHAILAL PATEL BHAILAL PATEL 6 NILKANTH PARK OPP VITHAL VADI NAVRANGPURA AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT AHMEDABAD 380009 000000000000C9A00169 1 5 ANANDGAURI BHANUPRASAD CHOKSY BHANUPRASAD CHOKSY NAGARWADA SONI S KHADKI NADIAD NADIAD INDIA GUJARAT KHEDA 387001 000000000000C9A00270 8 6 AMRUTLAL NAGARDAS BHAVSAR NAGARDAS BHAVSAR 154 NANI SALVIVAD PARAS PIPLA S KHANCHO SARASPUR AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT AHMEDABAD 380018 000000000000C9A00277 4 7 ANANDIBEN AMBALAL THAKKER AMBALAL THAKKER M/S ARVINDKUMAR AMBALAL THAKKAR DANAPITH KALUPUR AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT AHMEDABAD 380001 000000000000C9A00344 8 8 AMBALAL PURSHOTTAMDAS KACHHIA PURSHOTTAMDAS KACHHIA DHUDHI S KACHHIAWAD VASO VASO INDIA GUJARAT KHEDA 387380 000000000000C9A00361 8 9 AMBALAL PURSHOTTAMDAS CHHANALAL PURSHOTTAMDAS CHHANALAL 10 DHARMNATH CO OP HOUSING SOCIETY CAMP ROAD SAHIBAUG AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT AHMEDABAD 380004 000000000000C9A00362 2 10 ANILKUMAR CHIMANLAL SONI CHIMANLAL SONI NR UMIYA MATAJI S TEMPLE ASARWA AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT -

30 Killed in Two Mass Shootings in Us

Follow us on: RNI No. APENG/2018/764698 @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer Established 1864 Published From OPINION 6 MELANGE 11 SPORTS 12 VIJAYAWADA DELHI LUCKNOW THE GREAT PATIENCE AND FIRST TIME IN BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH WATER PARADOX POWER SHUTTLE HISTORY RANCHI BHUBANESWAR DEHRADUN HYDERABAD *Late City Vol. 1 Issue 280 VIJAYAWADA, MONDAY AUGUST 5, 2019; PAGES 12 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable BALAYYA TO PLAY LAWYER IN PINK REMAKE? { Page 9 } www.dailypioneer.com 2nd warning GODAVARI WATER DIVERSION TO SRISAILAM, NAGARJUNA SAGAR… signal at 30 KILLED IN TWO MASS Dowleswaram AP, TS govts wary of higher VIJAYAWADA: A second warning signal has been issued costs and time factor at Sir Arthur Cotton Barrage SHOOTINGS IN US in Dowleswaram as the flood PNS n HYDERABAD level in the river Godavari PNS n WASHINGTON/HOUSTON said the hospital was treating 11 crossed the 13 lakh cusecs El Paso victims. Nine were in The proposal of Chief Ministers mark Sunday morning. At At least 30 people were killed critical but stable condition and of Telangana and Andhra 11am, 13,43,836 cusecs flowed and several others injured in two two were stable, he said. Patient Pradesh, K Chandrasekhar Rao into the barrage and the same separate mass shootings within ages ranged from 35 to 82. and YS Jaganmohan Reddy was discharged into the delta 24 hours in the United States, The University Medical respectively, to divert Godavari canals and the sea. As the surge the latest in a string of mass Centre of El Paso received 13 water to the Krishna basin, of floodwater continued, many shootings in America. -

Amount of Unclaimed and Unapaid Dividend for the Financial Year 2013-14 MIDDLE FATHER's FATHER's LAST AMOUNT DUE DATE of SL

Amount of unclaimed and unapaid Dividend for the Financial Year 2013-14 MIDDLE FATHER'S FATHER'S LAST AMOUNT DUE DATE OF SL. No. FIRST NAME LAST NAME FATHER'S NAME ADDRESS COUNTRY STATE DISTRICT PINCODE FOLIONO INVESTMENT TYPE NAME MIDDLE NAME NAME (In Rs.) DEPOSIT TO IEPF 1205 1ST CROSS K BLOCK RAMAKRISHNA 1 MEERA CHANDRASHEKHAR CHANDRASHEKHAR INDIA KARNATAKA MYSORE 570022 0000IN30214810109808 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 30.00 30-OCT-2021 NAGAR MYSORE 570022 A-12, EKTA APARTMENTS L.B.S. MARG 2 MOHIT MURARI K MURARI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400080 000000000000000M6593 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 50.00 30-OCT-2021 MULUND(W) BOMBAY 400080 410/159 GOVERNMENT COLONY BANDRA 3 URMILA V DESHMUKH VILAS DESHMUKH INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400051 000000000000000U5205 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 92.00 30-OCT-2021 EAST BOMBAY 400051 333-B POCKET E LIG FLAT GTB ENCLAVE 4 JAI KUMAR SHARMA C K SHARMA INDIA DELHI EAST DELHI 110093 00000000000000027570 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 1.00 30-OCT-2021 DELHI 110093 WZ-10A STREET-1 SHIV NAGAR JAIL ROAD 5 NAVNEET KAUR REEN B S REEN INDIA DELHI WEST DELHI 110058 00000000000000027681 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 1.00 30-OCT-2021 JANAKPURI NEW DELHI 110058 5/288, 2ND FLOOR KHAN BLDG,ADVOCATE 6 RAJESHKUMAR MADANLAL GANDHI MADANLAL H GANDHI OFFICE ABOVE BHAVANIVAD P.O INDIA GUJARAT SURAT 395003 00000000000000051545 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 100.00 30-OCT-2021 HARIPURA,DUKAL POLE,SURAT 395003 C/O D L LAKHANI 5/533 MASIDIYA SHERI 7 SHYAM LAL -

In the Footsteps of the Maharajas

Sita, Tower B, Delta Square, MG Road, Sector 25 In the Footsteps Gurgaon-122001, Haryana, India T +91-124-470 3400 F +91-124-456 3100 [email protected] www.sita.in of the Maharajas KNOWLEDGE IS BASED ON EXPERIENCE EVERYTHING ELSE IS JUST INFORMATION Come explore wh us contents 06 delhi Story of the City Dear Friends, Story of the Taj Mahal Hotel Bespoke Experiences A LEGENDARY LAND of kingdoms and principalities, India till 1947 was in parts ruled by Maharajas, Nizams, Rajas, Ranas Special “Themed Dinner” Options and Rawals. Bards that roam the countryside still sing of heroic battles, chivalry and sacrifices. Silent, rocky outcrops transform 10 jaipur themselves into magnificent forts that stand sentinel over the Story of the City land. It is not difficult to imagine rank upon rank of loyal The Story of the Royal Family warriors streaming down the hillside ready for battle. If you Story of Rambagh Palace listen carefully, you may still hear faint echoes of clashing Bespoke Experiences armour, neighing of horses and above it all, the spine-chilling Special “Themed Dinner” Options trumpet of a charging elephant. Today, many of these former royals have opened their homes to visitors. Staying here is a travel back in time – to an era that was glorious, graceful and romantic. Starting from regal Delhi, the capital city of India, this 14 jodhpur two week itinerary takes you across what was once Rajputana Story of the City bringing alive the vibrant colours of the desert state. Visit the The Story of the Royal Family great kingdoms of former Rajputana – Jodhpur, Udaipur, Jaipur Story of Umaid Bhawan Palace and down south in the Deccan, Hyderabad.