Religion and Philanthropy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ecumenical Movement and the Origins of the League Of

IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by James M. Donahue __________________________ Mark A. Noll, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana April 2015 © Copyright 2015 James M. Donahue IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 Abstract by James M. Donahue This dissertation traces the origins of the League of Nations movement during the First World War to a coalescent international network of ecumenical figures and Protestant politicians. Its primary focus rests on the World Alliance for International Friendship Through the Churches, an organization that drew Protestant social activists and ecumenical leaders from Europe and North America. The World Alliance officially began on August 1, 1914 in southern Germany to the sounds of the first shots of the war. Within the next three months, World Alliance members began League of Nations societies in Holland, Switzerland, Germany, Great Britain and the United States. The World Alliance then enlisted other Christian institutions in its campaign, such as the International Missionary Council, the Y.M.C.A., the Y.W.C.A., the Blue Cross and the Student Volunteer Movement. Key figures include John Mott, Charles Macfarland, Adolf Deissmann, W. H. Dickinson, James Allen Baker, Nathan Söderblom, Andrew James M. Donahue Carnegie, Wilfred Monod, Prince Max von Baden and Lord Robert Cecil. -

Magazine of the Huddersfield Canal Society

ennine Link PMagazine of the Huddersfield Canal Society Issue 183 Autumn 2013 Huddersfield Canal Society Ltd Registered in England No. 1498800 Registered Charity No. 510201 Transhipment Warehouse, Wool Road, Dobcross, Oldham, Lancashire, OL3 5QR Office Hours: Monday - Thursday 08.30 -16.30 Friday 08.30 -13.30 Telephone: 01457 871800 EMail: [email protected] Website: www.huddersfieldcanal.com Patrons: Timothy West & Prunella Scales Council of Management Alan Stopher 101 Birkby Hall Road, Birkby, Huddersfield, Chairman West Yorkshire, HD2 2XE Tel: 01484 511499 Trevor Ellis 20 Batley Avenue, Marsh, Huddersfield, Vice-Chairman West Yorkshire, HD1 4NA Tel: 01484 534666 Mike McHugh HCS Ltd, Transhipment Warehouse, Wool Road, Dobcross, Treasurer Oldham, Lancashire, OL3 5QR Tel: 01457 871800 John Fryer Ramsdens Solicitors LLP, Oakley House, Company Secretary 1 Hungerford Road, Edgerton, Huddersfield, HD3 3AL Patricia Bayley 17 Greenroyd Croft, Birkby Hall Road, Huddersfield, Council Member West Yorkshire, HD2 2DQ Graham Birch HCS Ltd, Transhipment Warehouse, Wool Road, Dobcross, Council Member Oldham, Lancashire, OL3 5QR Tel: 01457 871800 Keith Noble The Dene, Triangle, Sowerby Bridge, Council Member West Yorkshire, HX6 3EA Tel: 01422 823562 Peter Rawson HCS Ltd, Transhipment Warehouse, Wool Road, Dobcross, Council Member Oldham, Lancashire, OL3 5QR Tel: 01457 871800 David Sumner MBE 4 Whiteoak Close, Marple, Stockport, Cheshire SK6 6NT President Tel: 0161 449 9084 Keith Sykes 1 Follingworth, Slaithwaite, West Yorkshire, HD7 5XD Council -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

The History of Huddersfield and Its Vicinity

THE HISTORY OF HUDDERSFIELD A N D I T S V I C I N I TY. BY D. F. E. SYI(ES, LL.B. HUDDERSFIELD: THE ADVERTISER PRESS, LIMITED. MDCCCXCV II I. TABLE OF CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. Physical features-Some place names-The Brigantes--Evidences of their settlement-Celtic relics at Cupwith Hill-At Woodsome At Pike-Law-At High-Flatts-Altar to God of the Brigantes Of the Celts-Voyage of Pytheas-Expeditions of Julius Ccesar -His account of the Celts-The Druids-The Triads-Dr. Nicholas on the Ancient Britons-Roman Rule in Britain Agricola's account-Roman roads-Roman garrisons-Camp at West Nab-Roman altar discovered at Slack (Cambodunum) Discoveries of Dr. \Valker-Roman hypocaust at Slack Explorations at Slack-Evidences of camp there-Schedule of coins found at Slack-Influence of Roman settlement-On government-On industries-On speech-Philological indications. CHAPTER II. The withdrawal of the Romans-Saxon influx-Evidences of Saxon settlement-Character of the Saxons-The Danes-Evidences of their settlement-Introduction of Christianity-Paulinus-Con version of Edwin-Church at Cambodunum-Other Christian stations - Destruction of Church at Cambodunum - Of the Normans-Invasion of William the Conqueror-Ilbert de Laci The feudal tenure-Domesday Book-Huddersfield and adjacent places in Domesday Book-Economic and social life of this period - The Villans - The Boardars - Common land - The descent of the Laci manor--The Earl of Lancaster -Richard Waley, Lord of Henley-The Elland Feud-Robin Hood-The Lord of Farnley and Slaithwaite-Execution of Earl of Lancaster -Forfeiture of Laci Manors to the Crown-Acquisition by the Ramsden family-Other and part owners-Colinus de Dameh·ill -Fules de Batona-John d' Eyville-Robert de Be11ornonte John del Cloghes-Richard de Byron-The Byron family in Huddersfield-Purchase by Gilbert Gerrard, temp. -

Civil Religion and Australia at War 1939-1945

Volume 11, Number 2 57 Images of God: civil religion and Australia at war 1939-1945 Katharine Massam and John H Smith1 One striking feature of the photographs recording the church services held regularly around Australia during the Second World War is the significant proportion 2 of men in the congregations • At the regular days of prayer called for by King George VI and supported by Australian governments during the war, and at the tumultuous celebrations of thanksgiving when peace was declared, men in uniform and in civilian dress are much more clearly present, if not over-represented, in the crowds. This is not what we expect of religious services in Australia. The assumption has been, sometimes even in the churches, that religion is women's work, and so at the margins of Australian civic life. However, both religion and war mark out the roles of women and men, at the same time as they provide a climate in which those roles can be 3 subverted • In Australia between 1939 and 1945 religious belief and the activities of the churches were entwined with the 'manly' conduct of the nation, and a variety of material reflecting the Australian experience of World War II suggests that the stereotype of religion as peripheral to public life. is limited and misleading. In statements of both church and state, religious belief was presented as crucial to civil defense, the moral character of the nation was seen as a key to victory, citizens (men as well as women) responded to calls to prayer and, on the homefront as well as the battlefield, women as well as men fought for a 'just and Godly peace'. -

“May You Live in Interesting Times…” Welcome to Our March/April Newsletter! As I “Stay at Home” to Write This Newsletter, the Famous Quote Above Springs to Mind

HLHS Members Newsletter March/April 2020 huddersfieldhistory.org.uk [email protected] We would like to hear from you! Please send any news, details of events and books, requests for information and comments that you think may be of interest to other Huddersfield Local History Society members to [email protected] Engraving of Storthes Hall, from Morehouse’s “The History and Topography of the Parish of Kirkburton and of the Graveship of Holme” (1861) “May You Live in Interesting Times…” Welcome to our March/April newsletter! As I “stay at home” to write this newsletter, the famous quote above springs to mind. However, if you thought that it was a “Chinese Curse”, you might be surprised to discover that research indicates it was in fact coined by Neville Chamberlain’s father in 1898. To help you pass the hours and days ahead, we’ve compiled a list of local history books and resources that you can access online. On behalf of the Committee, please stay safe and hopefully normality will be resumed in the not-too-distant future. Dave Pattern page 1 HLHS Publications Committee The Society’s most recent publication is Names, Places & Chair: People: a selection of articles from Old West Riding which Cyril Pearce was formally launched at our Annual Study Day. Priced at just £6.95 for 160 pages, copies are Vice-Chair: Brian Haigh available at our meetings or via our web site. Secretary: Old West Riding published 23 editions from 1981 Dave Pattern to 1995 and was a joint venture by three local Treasurer: historians – Jennifer Stead, Cyril Pearce and George Steve Challenger Redmonds. -

Linthwaite Circular Walk 2

worship. a listed building, no longer used as a place of of place a as used longer no building, listed a gave £3000 to the project. The chapel is now now is chapel The project. the to £3000 gave woollen manufacturers in Colne Valley, who who Valley, Colne in manufacturers woollen Reservoir and Castle Hill from Potato Road Potato from Hill Castle and Reservoir George Mallinson, one of the most important important most the of one Mallinson, George Jerusalem Farm Jerusalem Holme Cottage Farm with Blackmoorfoot with Farm Cottage Holme constructed as a result of the generosity of of generosity the of result a as constructed chapel building was was building chapel he t 1867 in Opened Linthwaite Methodist Church. Methodist Linthwaite plex. plex. com Church Methodist and the old chapel. Turn right into Stones Lane by the the by Lane Stones into right Turn chapel. old the and . care take Please then fork right up Chapel Hill past the Primary School School Primary the past Hill Chapel up right fork then hardest part of the walk is now over! over! now is walk the of part hardest with blind bends in both directions and no footways. footways. no and directions both in bends blind with pub (Grid Ref SE095 143). Walk up Hoyle House Fold, Fold, House Hoyle up Walk 143). SE095 Ref (Grid pub wall ahead, to reach a road (Holt Head Road). The The Road). Head (Holt road a reach to ahead, wall Warning. Linfit Lane at the point of entry is dangerous, dangerous, is entry of point the at Lane Linfit Warning. -

Huddersfield Suffrage Walks

Walking with suffrage in Huddersfield Huddersfield Station, St George’s Square By Jill Liddington WALK A 2 The Market Cross, Market hough smaller than Leeds Place or Bradford, Huddersfield Huddersfield is perhaps Yorkshire’s most Town Centre Among those heading for T Huddersfield in 1906 was Emmeline remarkable centre for suffrage history. With two hotly-fought Pankhurst. In her Manchester home Huddersfield Station, St three years previously she had formed a local by-elections in 1906-7, 1 George’s Square small, new suffrage group, the Women’s Huddersfield suffragettes were Social and Political Union (WSPU). regularly in the national news. Our walk begins at the station’s The WSPU had recently captured Alongside, an older-established impressive forecourt, its monumental newspaper headlines – interrupting suffragist organisation (which façade little changed since it was politicians by shouting their ‘Votes completed in 1850. Its magnificence for Women’ demands. This suffragette differed from the suffragettes reminds travellers of Huddersfield’s militancy, directed particularly at in using only constitutional prosperity among West Riding’s the Liberal Government, resulted in tactics) showed remarkable textile centres. By the early 1900s, the severe prison sentences. In October creativity and a talent for town centre was packed with great international networking. stone-built commercial offices and warehouses. In mills on the outskirts Now, a century later, we can walk long wool fibres were spun into yarn their streets, pace their neighbourhoods, which was then woven by women into visit their houses. Our first walk (A), a worsted and woollen cloth – often short circular route, takes us to the tweeds to be sewn into ready-made suffragettes’ campaigning locations suits and coats in nearby Leeds. -

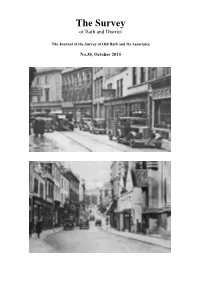

The Survey of Bath and District

The Survey of Bath and District The Journal of the Survey of Old Bath and Its Associates No.30, October 2015 The Survey of Bath and District No.30, 2015 THE SURVEY OF BATH AND DISTRICT The Journal of the Survey of Old Bath and its Associates Number 30 October 2015 CONTENTS City News: Bath Record Office Reports from Local Societies: Survey of Old Bath Friends of the Survey History of Bath Research Group Widcombe and Lyncombe Local History Society South Stoke History Committee The Freshford & District Local History Society Notes and Queries: The Diaries of Fanny Chapman A Bit more on the James Street West Labour Exchange Portway House, Weston Archaeology/Publications Articles: The Bladud Spa John Macdonald The Johnson Family of South Stoke, a Remarkable Parsonage Family Robert Parfitt The History of Broad Street - A Study of the Sites: Part I, The West Side Elizabeth Holland and Margaret Burrows Friends of the Survey: List of Members Editor: Mike Chapman, 51 Newton Road, Bath BA2 1RW tel: 01225 426948, email: [email protected] Layout and Graphics: Mike Chapman Printed by A2B Print Solutions, Pensford Front Cover Illustration: Lower Broad Street in the 1930s, looking South. Back Cover Illustration: Lower Broad Street in the 1940s, looking North. 1 The Survey of Bath and District No.30, 2015 CITY NEWS Bath Record Office We have made major progress this year on cataloguing the huge quantity of Council records held in the Record Office. This has been made possible by a significant grant in 2014 from the National Cataloguing Grant Programme for archives, and another in 2015 from the Heritage Lottery Fund. -

The Sermon in Nineteenth-Century British Literature and Society

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Victorian Sermonic Discourse: The Sermon in Nineteenth-Century British Literature and Society A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Jeremy Michael Sell June 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. John Ganim, Chairperson Dr. Susan Zieger Dr. John Briggs Copyright by Jeremy Michael Sell 2016 The Dissertation of Jeremy Michael Sell is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Anyone who has been through the trials and tribulations of graduate school and writing a dissertation knows that as solitary as it may at times seem, it is not a journey taken alone. I have many people to thank for helping bring this nearly-decade long sojourn to a successful conclusion. To begin, I want to remember Dr. Emory Elliott. His first book, Power and the Pulpit in Puritan New England, was one I discovered when I was first applying to PhD programs, and it gave me hope that there would be a professor at UCR who could relate to my interest in studying the sermon. After taking a course from him, I approached Dr. Elliott about chairing my committee; a journal entry I wrote the following day reads, “Dr. Elliott on board and enthusiastic.” But, not long afterwards, I received word that he unexpectedly and suddenly passed away. I trust that this work would have met with the same degree of enthusiasm he displayed when I first proposed it to him. With Dr. Elliott’s passing, I had to find someone else who could guide me through the final stages of my doctorate, and Dr. -

WEST YORKSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society a Photograph Exists for Milestones Listed Below but Would Benefit from Updating!

WEST YORKSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society A photograph exists for milestones listed below but would benefit from updating! National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position YW_ADBL01 SE 0600 4933 A6034 ADDINGHAM Silsden Rd, S of Addingham above EP149, just below small single storey barn at bus stop nr entrance to Cringles Park Home YW_ADBL02 SE 0494 4830 A6034 SILSDEN Bolton Rd; N of Silsden Estate YW_ADBL03 SE 0455 4680 A6034 SILSDEN Bolton Rd; Silsden just below 7% steep hill sign YW_ADBL04 SE 0388 4538 A6034 SILSDEN Keighley Rd; S of Silsden on pavement, 100m south of town sign YW_BAIK03 SE 0811 5010 B6160 ADDINGHAM Addingham opp. Bark La in narrow verge, under hedge on brow of hill in wall by Princefield Nurseries opp St Michaels YW_BFHA04 SE 1310 2905 A6036 SHELF Carr House Rd;Buttershaw Church YW_BFHA05 SE 1195 2795 A6036 BRIGHOUSE Halifax Rd, just north of jct with A644 at Stone Chair on pavement at little layby, just before 30 sign YW_BFHA06 SE 1145 2650 A6036 NORTHOWRAM Bradford Rd, Northowram in very high stone wall behind LP39 YW_BFHG01 SE 1708 3434 A658 BRADFORD Otley Rd; nr Peel Park, opp. Cliffe Rd nr bus stop, on bend in Rd YW_BFHG02 SE 1815 3519 A658 BRADFORD Harrogate Rd, nr Silwood Drive on verge opp parade of shops Harrogate Rd; north of Park Rd, nr wall round playing YW_BFHG03 SE 1889 3650 A658 BRADFORD field near bus stop & pedestrian controlled crossing YW_BFHG06 SE 212 403 B6152 RAWDON Harrogate Rd, Rawdon about 200m NE of Stone Trough Inn Victoria Avenue; TI north of tunnel -

Joseph H Choate

President JOSEPH H CHOATE Vic e-Presidents E M R J . Pl RPONT O GAN R L L R A LE B E F B AD MI A O D CH R S ER S RD G . C . O , uNLl FFE - WEN F . C O WILSON G EORG E T . Treasurer W U RTIS DEM REST M. C O 60 ibert St . New ork L y , Y Sec retary BU RLEl G H G EORGE W . 5 2 Wall Sr. New ork , Y E xec utive Committee WIL N a an GE RG E T . SO C O , h irm A a L C a s B sf n W . G s dmir l ord h rle ere ord , %oh rigg H a Loui s C . y Mann n D . O . G W B W T . Rev . eorge . urleigh i g , N c as M a B P nt M an i hol urr y utler J . ierpo org Willi am Allen But ler Herbert Noble H . a n Joseph Cho te Robert C . Ogde E . F . D a F C n ff w n rrell . u li e O e P a k Wm . Curti s Demorest Alt on B . r er a H t L . S at Ch unc ey M. Depew erber terlee w t . H . A S R E a R . C . rt . mi h Sa W Fa c a s S muel . ir hild % me pey er Law L G G G a a renc e . illespie eorge r y W rd H F r c k .