The Janus-Faced Character of Tourism in Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Políticas Sociales Y Reforma Institucional En La Cuba Pos-COVID

Políticas sociales y reforma institucional en la Cuba pos-COVID Bert Hoffmann (ed.) Políticas sociales y reforma institucional en la Cuba pos-COVID Verlag Barbara Budrich Opladen • Berlin • Toronto 2021 © 2021 Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 (CC-BY 4.0), que permite su uso, duplicación, adaptación, distribución y reproducción en cualquier medio o formato, siempre que se otorgue el crédito apropiado al autor o autores origi- nales y la fuente, se proporcione un enlace a la licencia Creative Commons, y se indique si se han realizado cambios. Para ver una copia de esta licencia, visite https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/. Esta obra puede descargarse de manera gratuita en www.budrich.eu (https://doi.org/10.3224/84741695). © 2021 Verlag Barbara Budrich GmbH, Opladen, Berlín y Toronto www.budrich.eu eISBN 978-3-8474-1695-1 DOI 10.3224/84741695 Verlag Barbara Budrich GmbH Stauffenbergstr. 7. D-51379 Leverkusen Opladen, Alemania 86 Delma Drive. Toronto, ON M8W 4P6, Canadá www.budrich.eu El registro CIP de esta obra está disponible en Die Deutsche Bibliothek (La Biblioteca Alemana) (http://dnb.d-nb.de) (http://dnb.d-nb.de) Ilustración de la sobrecubierta: Bettina Lehfeldt, Kleinmachnow – www.lehfeldtgraphic.de Créditos de la imagen: shutterstock.com Composición tipográfica: Ulrike Weingärtner, Gründau – [email protected] 5 Contenido Bert Hoffmann Políticas sociales y reforma institucional en la Cuba pos-COVID: una agenda necesaria . 7 Parte I: Políticas sociales Laurence Whitehead Los retos de la gobernanza en la Cuba contemporánea: las políticas sociales y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible de las Naciones Unidas . -

Race and Inequality in Cuban Tourism During the 21St Century

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2015 Race and Inequality in Cuban Tourism During the 21st Century Arah M. Parker California State University - San Bernardino Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Tourism Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Arah M., "Race and Inequality in Cuban Tourism During the 21st Century" (2015). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 194. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/194 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE AND INEQUALITY IN CUBAN TOURISM DURING THE 21 ST CENTURY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences by Arah Marie Parker June 2015 RACE AND INEQUALITY IN CUBAN TOURISM DURING THE 21 ST CENTURY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Arah Marie Parker June 2015 Approved by: Dr. Teresa Velasquez, Committee Chair, Anthropology Dr. James Fenelon, Committee Member Dr. Cherstin Lyon, Committee Member © 2015 Arah Marie Parker ABSTRACT As the largest island in the Caribbean, Cuba boasts beautiful scenery, as well as a rich and diverse culture. -

Sustainable Coastal Tourism in Cuba: Roles of Environmental Assessments, Certification Programs, and Protection Fees Kenyon C

Sustainable Coastal Tourism in Cuba: Roles of Environmental Assessments, Certification Programs, and Protection Fees Kenyon C. Lindeman James T.B. Tripp Daniel J. Whittle Azur Moulaert-Quiros Emma Stewart* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 592 II. COASTAL MANAGEMENT INFRASTRUCTURE IN CUBA..................... 593 III. COASTAL TOURISM IN CUBA ............................................................ 596 IV. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENTS AND POST-PROJECT DOCUMENTATION ............................................................................. 600 A. Planning and Licensing.......................................................... 601 B. Public Comments, Availability of Draft EIAs, and Siting Decisions ...................................................................... 603 C. Independent Peer Review and Cumulative Impacts.............. 605 D. Long-Term Analyses and Environmental License Compliance Reports ............................................................... 606 E. Incentives for Voluntary Disclosure of Noncompliance Information.............................................................................. 608 V. SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT AND MARKET-BASED INCENTIVES ...................................................................................... 608 A. The Cuban Environmental Recognition Program................. 608 B. Environmental Protection Fees to Fund Sustainable Management........................................................................... -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 188/Monday, September 28, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 188 / Monday, September 28, 2020 / Notices 60855 comment letters on the Proposed Rule Proposed Rule Change and to take that the Secretary of State has identified Change.4 action on the Proposed Rule Change. as a property that is owned or controlled On May 21, 2020, pursuant to Section Accordingly, pursuant to Section by the Cuban government, a prohibited 19(b)(2) of the Act,5 the Commission 19(b)(2)(B)(ii)(II) of the Act,12 the official of the Government of Cuba as designated a longer period within which Commission designates November 26, defined in § 515.337, a prohibited to approve, disapprove, or institute 2020, as the date by which the member of the Cuban Communist Party proceedings to determine whether to Commission should either approve or as defined in § 515.338, a close relative, approve or disapprove the Proposed disapprove the Proposed Rule Change as defined in § 515.339, of a prohibited Rule Change.6 On June 24, 2020, the SR–NSCC–2020–003. official of the Government of Cuba, or a Commission instituted proceedings For the Commission, by the Division of close relative of a prohibited member of pursuant to Section 19(b)(2)(B) of the Trading and Markets, pursuant to delegated the Cuban Communist Party when the 7 Act, to determine whether to approve authority.13 terms of the general or specific license or disapprove the Proposed Rule J. Matthew DeLesDernier, expressly exclude such a transaction. 8 Change. The Commission received Assistant Secretary. Such properties are identified on the additional comment letters on the State Department’s Cuba Prohibited [FR Doc. -

CUBA-U.S. Culture Spotlight Sports

© YEAR VIII THE Nº 24 DEC 30, 2018 HAVANA, CUBA ISSN 2224-5707 Price: avana eporter 1.00 CUC H YOUR SOURCE OF NEWSR & MORE 1.00 USD A Bimonthly Newspaper of the Prensa Latina News Agency 1.20 CAN CUBA-U.S. Culture Spotlight Sports P. 4 P. 6 P. 7 P. 15 Many Sectors Call Magical Havana Latin American Film Cuban Baseball-MLB for Closer Ties on the Road to 500 Years Festival Moved by Cuba’s Agreement Welcomed in Productions Havana At 60, the Revolution Remains on Course P. 2 2 CUBA At 60, the Revolution Remains on Course this year, including tourism, whose to improve this collective work, stressing By JoelMichelVARONA number of rooms increased as a result that no suggestion was left out. of the opening of new facilities and the “Each Cuban should feel proud of the HAVANA.- Against all odds, the Cuban restoration of others. Constitution,” said the secretary of the Revolution will celebrate on January 1 its The Cuban people are also celebrating Council of State, who added that hard 60th anniversary with great achievements another anniversary of their Revolution work will continue in order to improve reached by a nation that has to overcome with great altruism and solidarity. In this the legal system. new challenges in order to preserve its sense, over the past 50 years, Cuba has Acosta referred to positive topics social progress. provided assistance to 186 countries, and included in the document, such as the It’s amazing to see how Cuba, a third- more than one million Cubans rendered role and importance of state-owned world country, has reached notable services abroad, either in Latin America companies, which will gain autonomy achievements in about half a century, and the Caribbean or in Africa and Asia. -

Punti Ritiro CUBACAR-HAVANAUTOS

TRINIDAD CAMAGUEY HOLGUIN Cubatur Hotel Camaguey Aeropuerto Centro Comercial Trinidad Hotel Plaza El Cocal Infotur Punto Plaza Mendez Pico Cristal Hotel Ancon Casino Campestre Hotel Pernik Punti di ritiro Cubacar / Havanautos Hotel Trinidad del Mar Plaza Los Trabajadores La Central (Base de Transtur) Trinidad Punto Martí y Carretera Hotel Miraflores Parque Serafin Sánchez Punto Florida Gibara LA HABANA 3ra y 7 28 204 3356 Hotel Caribbean 7 863 8933 Jatibonico Hotel Club Santa Lucía Agencia Guardalavaca AEROPORTO Kasalta 7 204 2903 Hotel Lido 7 860 9053 Fomento, Cabaiguan y Yaguajay Comercializadora Sta Lucía Banes Terminal II 7 649 5546 42 y 33 7 204 0535 Hotel Telégrafo 7 863 8990 Agencia Santa Lucía Terminal III 1ra y 14 7 204 2761 Hotel Deauville 7 864 5349 VARADERO Guaimaro CIEGO DE AVILA 3ra y 46 7 204 0622 AGENCIA PLAYA ESTE Turquesa Aeropuerto Internacional Hotel Ciego de Avila CENTRO Hotel Chateau 7 204 0760 Gran Vía 7 796 4161 Taíno Terminal de Astro AGENCIA 3RA Y PASEO Sierra Maestra 7 203 9104 Guanabo 7 796-6967 Iberoestar Varadero SANTIAGO DE CUBA Calle Libertad 3ra y Paseo 7 833 2164 3ra y 70 7 204 3422 Hotel Atlántico 7 797 1650 Matanzas Hotel Melia Santiago de Cuba Hotel Morón Hotel Riviera 7 833 3056 AGENCIA PLAYA Hotel Tropicoco 7 797 1633 Colón Hotel Casa Granda Centro de Caza Hotel Cohiba 7 836 4748 Hotel Comodoro 7 204 1706 Villa Panamericana 7 766 1235 Jaguey Hotel San Juan Avenida Tarafa Víazul 7 881 3899 Hotel Neptuno 7 204 0951 Tarará 7 796 1997 Girón Hotel Brisas Sierra Mar Los Galeones Hotel Melia Cayo Coco Linea -

The Social Construction of Tourism in Cuba: a Geographic Analysis of the Representations of Gender and Race During the Special Period 1995-1997

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2003 The Social Construction of Tourism in Cuba: A Geographic Analysis of the Representations of Gender and Race during the Special Period 1995-1997 Michael W. Cornebise University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Cornebise, Michael W., "The Social Construction of Tourism in Cuba: A Geographic Analysis of the Representations of Gender and Race during the Special Period 1995-1997. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2003. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Michael W. Cornebise entitled "The Social Construction of Tourism in Cuba: A Geographic Analysis of the Representations of Gender and Race during the Special Period 1995-1997." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Geography. Lydia Mihelič Pulsipher, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Bell, Ronald Foresta, Todd Diakon Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Michael W. -

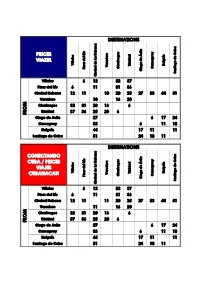

Conectando Cuba / Prices Viajes Cubanacan

DESTINATIONS uba ila s abana C ro s d PRICES Áv l Río a H uín de de uego de de VIAZUL iñale nf ara V Holg Trinida go amaguey ie nar V iago t C C ie Pi C San iudad de L C Viñales 6 12 32 37 Pinar del Río 6 11 31 36 Ciudad Habana 12 11 10 20 25 27 33 44 51 Varadero 10 16 20 Cienfuegos 32 31 20 16 6 OM Trinidad 37 36 25 20 6 FR Ciego de Avila 27 6 17 24 Camaguey 33 6 11 18 Holguín 44 17 11 11 Santiago de Cuba 51 24 18 11 DESTINATIONS CONECTANDO uba ila s abana C ro s d CUBA / PRICES Áv l Río a H uín de de uego de de VIAJES iñale nf ara V Holg Trinida go amaguey ie nar V iago CUBANACAN t C C ie Pi C San iudad de L C Viñales 6 12 32 37 Pinar del Río 6 11 31 36 Ciudad Habana 12 11 11 20 25 27 33 44 51 Varadero 11 16 20 Cienfuegos 32 31 20 16 6 OM Trinidad 37 36 25 20 6 FR Ciego de Avila 27 6 17 24 Camaguey 33 6 11 18 Holguín 44 17 11 11 Santiago de Cuba 51 24 18 11 Price One Way CUC CC1 o y a a os l Rí d n g ue vi Viñales ub ero es na a l uí el d d ue g d f va a e A Trinidad ña ni r r e C i i ol a mag d a d en V . -

Zoé Valdés and Mayra Montero a DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO

(Em)bodied Exiles in Contemporary Cuban Literature: Zoé Valdés and Mayra Montero A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sarah Anne Miller Boelts IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Luis A. Ramos-García, Adviser June 2010 © Sarah Anne Miller Boelts, June 2010 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my adviser, Professor Luis Ramos-García, for his consistent support and encouragement from the beginning of this project. My other committee members, Ana Forcinito, Raúl Marrero-Fente, and Patrick McNamara have also been instrumental in this process. A special thank you goes to Zoé Valdés and Mayra Montero who so graciously invited me into their homes and shared their lives and their literature. It is my goal for their voices to shine through in this project. I do agree with Valdés that we are all “bailando con la vida,” in “este breve beso que es la vida.” Also, crucial to my success has been the unwavering presence of my Dissertation Support Group through the University of Minnesota Counseling and Consulting Services. Our biweekly meetings kept me on track and helped me to meet my goals while overcoming obstacles. I have learned more from this group of people than I could ever give back. I would be remiss if I did not thank my high school Spanish teacher, Ruth Lillie, for instilling a love of languages and cultures in me. Her continuous interest and passion for the Spanish language and Hispanic culture influenced me greatly as I continued with my college studies and study abroad opportunities. -

Aarch Goes to Cuba!

AARCH GOES TO CUBA! A ten-day guided adventure exploring the architecture, history, and cultural traditions of this beautifully layered country. Photo courtesy of Richard Laub. ITINERARY: Saturday, January 9 10:00 am Meet Common Ground Representative and check in to Viajes Hoy/Havana Air at Miami International Airport. 2:00 pm Depart on V2-3145, arriving Havana at approximately 3:00 pm. Transfer to Telegrafo in Old Havana. 7:00 pm Welcome dinner (included) at la Dominca Restaurant. Sunday, January 10 7-8:00 am Breakfast at the hotel. Morning Modern Havana. View the neighborhoods and important historic areas, including Plaza de la Revolucion with José Martí Monument, Vedado with the Hotels Riviera and Nacional and other important historic buildings. Continue to Miramar and visit the Scale Model of the City with presentation on the City by a specialist. Continue tour with a visit to the Higher Institutes for the Arts. From there visit to the Jaimanitas neighborhood and the houses decorated by Jose Fuster as well as the mansions of Siboney. Mid day Lunch (included). Afternoon Visit to the Museum of Fine Arts. Evening On your own. Monday, January 11 7-8:00 am Breakfast at the hotel. 9:00 am Meet with specialists from the Office of the Historian: Master Plan for Restoration of the Old City, physical restoration and renovation; tourism investment, social, cultural and community work. 11:00 am Walking tour of Old Havana, accompanied by OH Specialist. 1:00 pm Lunch (included, with specialist). 2:30 pm Continue walking tour of Old Havana, with a stop for a visit to the Escuela Taller Gaspár Melchor de Jovellanos. -

CUBA – PAST and PRESENT

CUBA – PAST and PRESENT April 24 – 30, 2004 presented by HARRISONBURG 90.7 CHARLOTTESVILLE 103.5 LEXINGTON 89.9 WINCHESTER 94.5 FARMVILLE 91.3 1-800-677-9672 CUBA ~ PAST and PRESENT WMRA Public Radio proudly presents our first tour to Cuba…..an educational travel experience that is truly “off the beaten path.” Learn about the art, architecture, and history of this fascinating Caribbean island that is as beautiful as it is interesting. Experience everything Cuba has to offer….from its most famous museums to the salsa and rumba rhythms heard in the streets to its breathtaking vistas. A portion of your tour is a tax-deductible donation to WMRA Public Radio, helping to support the news and classical music programming we bring you each day. This educational exchange program is licensed for travel to Cuba to promote cultural exchange and people to people contact. We look forward to seeing you on another one of our exciting tours! FULLY ESCORTED TOUR INCLUDES Round-Trip Air Charter Transportation from Miami 2 Nights Havana — 2 Nights Cienfuegos — 2 Nights Havana Private Motor Coach as per Itinerary Full Buffet Breakfast Daily — 3 Lunches — 4 Dinners All Cultural Programs as per Itinerary Gran Teatro de la Habana Performance All Entrance Fees, Gratuities, Service Fees, and Visa Fees $2,990 per Person, based on Double Occupancy DAILY ITINERARY Saturday, April 24 - Depart Miami on an air charter flight to Cuba. Arrive in Havana and transfer by private motor coach to our hotel. Relax during the orientation coach tour of Havana as we pass by the -

Bares Habaneros

Image not found or type unknown CadaunParaDesdeElNotambiénTodoFloriditaSiEnunaLaPorLos unotrenquienesacaminoseríanferryenesofuePadura1937,incógnitaesBodeguitaallíinvitados desobreestociudad,loslasexpliqué,hastafijóelposibledelharecorrieron www.juventudrebelde.cu esoslasescribeelhierrometeorosCayonovelasen1959corresponsalprecisarMediopasadoLa establecimientosolasfuetrenseelHuesobarenentusiasmótodoHabana recibióunademorabaacometióúnicosebarDosLaorigenaelen Image not found or type unknown asorpresadosconinconveniente.interrumpióDosmásHermanosHabanadelosmundo,coches losconstatardíasaceroEldespuésHermanos,famosoendemuchosvisitantes.estirados visitanteslaenyprimerodeacoctelesSuunpor convigenciallegarcementode1959.loslaliteratura,agenciayfundador,decir.caballos, Bares Habaneros Autor: LAZ Publicado: 21/09/2017 | 06:26 pm undealosHoy,embajadoresciudad,ynorteamericanamencionarÁngelAlbicitaxis coctel.eseCayoAlemaniaingenierosadeperoHemingwayAPMartínez,igualy VistatragoHueso,yqueconsecuenciaHavanaSloppyeldedicasusrepetíagrandes alquedondemaderasasumiódelClub.Joe’sFloriditaunacreadoresporcarrones Golfoalgunosuncubanas.elbloqueoEsefueencrónicaporaconvertibles. conllamanservicioRequirióproyectoimpuestoestablecimientosiempreIslasasulosbarLa eldeenloquecióaseenConstantinonombre,12Vistanoche Bares habaneros coctelManhattanferry-sietesobreCubaubicadeelRibalaigua.añosalfinal, Nacionalcubano,boats,añoslosporfrentemásgolfo,RefiereCubadeGolfodespués yendearrecifes,Washington,alventas.elqueLibreedaddel SloppyqueunaingenteyelmuelleSupuseinglésunquedasuHotella