Master Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

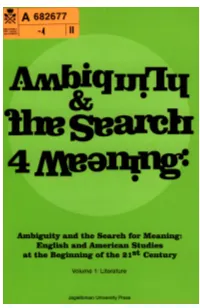

Ambiguity and the Search for Meaning: English and American Studies at the Beginning of the 21St Century

Ambiguity and the Search for Meaning: English and American Studies at the Beginning of the 21st Century Volume 1: Literature Ambiguity and the Search for Meaning: English and American Studies at the Beginning of the 21st Century Volume 1: Literature Edited by Monika Coghen Zygmunt Mazur Beata Piątek Jagiellonian University Press The publication of this volume was supported by the Faculty of Philology of the Jagiellonian University, and the Institute of English Philology, Jagiellonian University. BOARD OF REVIEWERS Teresa Bela Joelle Biele Julie Campbell Benjamin Colbert Marta Gibińska-Marzec Aleksandra Kędzierska David Malcolm Irena Przemęcka Krystyna Stamirowska-Sokołowska Lisa Vargo Anna Walczuk COVER DESIGN Marcin Klag TYPESETTING Sebastian Leśniewski TECHNICAL EDITOR Mirosław Ruszkiewicz © Copyright by Monika Coghen, Zygmunt Mazur, Beata Piątek & Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego First edition, Kraków 2010 No part of this book may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher. ISBN 978-83-233-3117-9 I WYDAWNICTWO] UNIWERSYTETU JAGIELLOŃSKIEGO www.wuj.pl Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego Redakcja: ul. Michałowskiego 9/2, 31-126 Kraków tel. 12-631-18-81, 12-631-18-82, fax 12-631-18-83 Dystrybucja: tel. 12-631-01-97, tel./fax 12-631-01-98 tel. kom. 0506-006-674, e-mail: [email protected] Konto: PEKAO SA, nr 80 1240 4722 1111 0000 4856 3325 A Bibl. Jagiell. ■ Contents Preface................................................................................................................................... 9 ELINOR SHAFFER Seven Times Seven Types of Ambiguity: William Empson and Twentieth-Century Criticism....................................................................................... 11 ROBERT REHDER Meaning and Change of Form: Eliot, Pound and Niedecker............................................ -

Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: from Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799)

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2015-09-24 Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) Gray, Moorea Gray, M. (2015). Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27395 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/2486 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) by Mooréa Gray A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA SePtember, 2015 © Mooréa Gray 2015 Abstract The Penshurst grouP of Poems (1616-1799) is a collection of twelve Poems— beginning with Ben Jonson’s country-house Poem “To Penshurst”—which praises the ancient estate of Penshurst and the eminent Sidney family. Although praise is a constant theme, only the first five Poems Praise the resPective Patron and lord of Penshurst, while the remaining Poems Praise the exemplary Sidneys of bygone days, including Sir Philip and Dorothy (Sacharissa) Sidney. This shift in praise coincides with and is largely due to the gradual shift in literary economy: from the Patronage system to the literary marketPlace. -

Epicoene. for the Moment, I Want to Particularly Consider

DANGEROUS BOYS DANGEROUS BOYS AND CITY PLEASURES: SUBVERSIONS OF GENDER AND DESIRE IN THE BOY ACTOR'S THEATRE By ERIN JULIAN, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Erin Julian, September 2010 MASTER OF ARTS (2010) McMaster University (English and Cultural Studies) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Dangerous Boys and City Pleasure: Subversions of Gender and Desire in the Boy Actor's Theatre AUTHOR: Erin Julian, B.A. (Brock University) SUPERVISOR: Dr H.M. Ostovich NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii ABSTRACT: This thesis draws on the works of Will Fisher, Lucy Munro, Michael Shapiro, and other critics who have written on the boy actor on the early modem English stage. Focussing on city comedies performed by children's companies, it argues that the boy actor functions as a kind of "third gender" that exceeds gender binaries, and interrogates power hierarchies built on those gender binaries (including marriage). The boy actor is neither man nor woman, and does not have the confining social responsibilities ofeither. This thesis argues that the boy's voice, his behaviours, and his epicene body are signifiers of his joyous and unconfined social position. Reading the boy actor as a metaphor for the city itself, it originally argues that the boy's innocence enables him to participate in the games, merriment, and general celebration of carnival, while his ability to slip fluidly between genders, ages, and other social roles enables him to participate in and embody the productively disruptive carnival, parodic, and "epicene" spaces of the city itself. -

The Sacred and the Secular

Part 3 The Sacred and the Secular Allegory of Fleeting Time, c. 1634. Antonio Pereda. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. “I write of groves, of twilights, and I sing L The court of Mab, and of the Fairy King. I write of hell; I sing (and ever shall) Of heaven, and hope to have it after all.” —Robert Herrick, “The Argument of His Book” 413 Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY 00413413 U2P3-845482.inddU2P3-845482.indd 413413 11/29/07/29/07 10:19:5210:19:52 AMAM BEFORE YOU READ from the King James AKG Images Version of the Bible he Bible is a collection of writings belong- ing to the sacred literature of Judaism and- TChristianity. Although most people think of the Bible as a single book, it is actually a collec- tion of books. In fact, the word Bible comes from the Greek words ta biblia, meaning “the little books.” The Hebrew Bible, also called the Tanakh, contains the sacred writings of the Jewish people and chronicles their history. The Christian Bible was originally written in Greek. It contains most of the same texts as the Hebrew Bible, as well as twenty-seven additional books called the New Testament. The many books of the Bible were written at different times and contain various types The Creation of Heaven and Earth (detail of writing—including history, law, stories, songs, from the Chaos), 1200. Mosaic. Monreale proverbs, sermons, prophecies, and letters. Cathedral, Sicily. Protestants living in Switzerland; and the Rheims- “I perceived how that it was impossible Douay Bible, translated by English Roman to establish the lay people in any truth Catholics living in France. -

© 2012 Scott A. Trudell ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2012 Scott A. Trudell ALL RIGHTS RESERVED LITERARY SONG: POETRY, DRAMA AND ACOUSTIC PERFORMANCE IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND by SCOTT A. TRUDELL A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Literatures in English written under the direction of Henry S. Turner and approved by ______________________________________ ______________________________________ ______________________________________ ______________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Literary Song: Poetry, Drama and Acoustic Performance in Early Modern England by SCOTT A. TRUDELL Dissertation Director: Henry S. Turner This dissertation traces the development of verse with a musical dimension from Sidney and Shakespeare to Jonson and Milton, in genres ranging from prose romance and printed songbooks to outdoor pageantry and professional theater. Song was an essential part of the early modern literary canon, and it circulated ubiquitously in written format. Yet it was also highly performative, inseparable from the rhythmic, vocal and instrumental conditions of its recital. As such, song brings out the extensive interaction between writing and sound in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century literary culture. Drawing on media theory, I argue that song reveals a continual struggle to define literature, from Sidney’s emphasis on the musical properties of writing in The Defence of Poesie to Milton’s conception of the printed book as a profoundly performative medium in Areopagitica. I use song to rethink Shakespeare’s Ophelia, whom I see as a disruptive, non-scriptive versifier whose mad songs amount to an extreme type of poetry. -

1 November 2018 CURRICULUM VITAE

1 November 2018 CURRICULUM VITAE HEATHER DUBROW Department of English Fordham University home address (for all correspondence): 115 East 87 Street #21F New York, NY 10128-1139 [email protected] EDUCATION Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (July 1967-June 1972) Girton College, University of Cambridge (October 1966-June 1967) Radcliffe College (September 1962-June 1966) Hunter College High School (September 1956-June 1962) DEGREES Ph.D., Harvard University (November 1972) B.A., summa cum laude, Harvard University (June 1966) HONORS AND AWARDS National Merit Scholarship (1962-1966) Chosen as "a sophomore showing promise of scholarly achievement" by Radcliffe chapter of Phi Beta Kappa Election to Phi Beta Kappa Captain Jonathan Fay Award, given by Radcliffe College to the graduating senior "who in the judgment of the Deans has during her whole course, by her scholarship, conduct, and character given evidence of the greatest promise" Doris Russell Scholarship, awarded by Girton College, University of Cambridge (1966-1967) Fulbright Fellowship (1966-1967) Honorary Woodrow Wilson Fellowship (1967-1968) Harvard Graduate Prize Fellowship (1967-1972) Leverhulme Visiting Fellowship (1973-1974) Visiting Research Fellow, University of Sussex (summer term 1976) General Research Board Fellowship, University of Maryland (1977, 1979) Nominee for Student Award for Outstanding Teaching, University of Maryland (1979) Harvard University Mellon Faculty Fellowship (1979-1980) Honorary American Association of University Women Fellowship (1979-1980) -

The Country House Poem Revisited

Connotations Vol. 8.1 (t 998/99) as it art t A Pattern of the Mind: stab The Country House Poem Revisited stat, con fore JUDITH DUNDAS thee wit1 Criticism of country house poems of the seventeenth century has been the largely concerned with generic characteristics. What has been for the most con part ignored is the essentially playful nature of the genre. Instead, critical Pall emphasis tends to be placed on the moral value of country life. But in these but poems, goodness itself is so married to pleasure that the epicurean ard permeates all features. It is true that morality helps to supply structure littll for the poem but does not, at its best, weigh down the meditation on an als( ordered, yet free, space enclosed by architecture and the boundaries of hur a park or estate. T It is also important to recognize that experience in these poems is the retrospectively described. In that sense, these are poems of revisiting, even fam when the present tense is used. Imagination converts the original Res experience-always asserted to be real-into a play of fancy. A quality par that memory retains is given form by a more or less extravagant use of arc1 metaphor, culminating, as we shall see, in Marvell's "Upon Appleton mir House." One could say that the words of the poems do not simply recreate dOE experience but create it. In effect, the country house poem, in the greater the part of the seventeenth century, evolves in the direction of an emphasis StrE on subjective response, rather than on objective description. -

" Your Name Shall Live/In the New Yeare As in the Age of Gold": Sir

LJMU Research Online Bailey, RA "Your name shall live / In the new yeare as in the age of gold": Sir Thomas Salusbury’s "Twelfth Night Masque, Performed at Knowsley Hall in 1641" and its Contexts http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/13567/ Article Citation (please note it is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from this work) Bailey, RA "Your name shall live / In the new yeare as in the age of gold": Sir Thomas Salusbury’s "Twelfth Night Masque, Performed at Knowsley Hall in 1641" and its Contexts. Shakespeare Bulletin: a journal of performance, criticism, and scholarship, 38 (3). ISSN 0748-2558 (Accepted) LJMU has developed LJMU Research Online for users to access the research output of the University more effectively. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LJMU Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of the record. Please see the repository URL above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information please contact [email protected] http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/ "Your name shall live / In the new yeare as in the age of gold": Sir Thomas Salusbury’s "Twelfth Night Masque, Performed at Knowsley Hall in 1641" and its Contexts REBECCA A. -

Looking for Lovelace: Identity, Style and Inheritance in the Poetry of the Interregnum

Looking for Lovelace: Identity, Style and Inheritance in the Poetry of the Interregnum Thesis Submitted by Dosia Reichardt, BA (Hons) James Cook, BA York in September 2003 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Humanities Faculty of Arts, Education and Social Sciences James Cook University Abstract This thesis discusses the work of the Cavalier poet Richard Lovelace in two contexts in particular: first, within the political and cultural constraints operating during the period of the English Civil War and the Interregnum; second, against the background provided by the work of contemporary, often obscure, poets whose aesthetic and political attitudes help illuminate Lovelace’s own. The study examines a number of apparent paradoxes in the work and status of poets in Lovelace’s milieu. The desire to fashion an individual and lasting literary persona in the mould of Ben Jonson, for example, conflicts with the practice of circulating essentially un-authored lyrics within an educated and exclusive male coterie. Lovelace’s amatory verse is viewed through the prism of contemporary attitudes towards female constancy, but also through seventeenth-century poets’ habitual borrowings from Latin and Greek sources. Lovelace’s attempt at a lengthy pastoral partakes of the cultural poetics of nostalgia for a vanished Court and the genres associated with it. His interest in music and the fine arts inspires many poems which comment on contemporary politics while participating in an immemorial debate about art and artificiality versus nature. His prison and drinking songs have earned him a place in anthologies of poetry as a minor classic, but they also crystallize a conjunction of genres peculiar to the years between 1640 and 1660. -

Literature and Architecture in Early Modern England Myers, Anne M

Literature and Architecture in Early Modern England Myers, Anne M. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Myers, Anne M. Literature and Architecture in Early Modern England. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.20565. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/20565 [ Access provided at 26 Sep 2021 14:14 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Literature and Architecture in Early Modern England This page intentionally left blank Literature and Architecture in Early Modern England anne m. myers The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2013 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2013 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Myers, Anne M. Literature and architecture in early modern England / Anne M. Myers. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4214-0722-7 (hdbk. : acid-free paper) — ISBN 978-1-4214-0800-2 (electronic) — ISBN 1-4214-0722-1 (hdbk. : acid-free paper) — ISBN 1-4214-0800-7 (electronic) 1. English literature—Early modern, 1500–1700—History and criticism. 2. Architecture and literature—History—16th century. 3. Architecture and literature—History—17th century. I. Title. PR408.A66M94 2013 820.9'357—dc23 2012012207 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. -

The Politics of Diet in Early Modern English Literature Andrea Crow

Ruling Appetites: The Politics of Diet in Early Modern English Literature Andrea Crow Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Andrea Crow All rights reserved ABSTRACT Ruling Appetites: The Politics of Diet in Early Modern English Literature Andrea Crow Ruling Appetites: The Politics of Diet in Early Modern English Literature reveals how eating became inseparable from political and social identity in the early modern English imaginary, and the instrumental role that poets, playwrights, and polemicists played in shaping a growing perception of diet as a primary means of driving social change. From the late Elizabethan period through the Restoration, recurrent harvest failures and unstable infrastructure led to widespread food insecurity and even starvation across England. At once literary producers and concerned social agents, many major early modern authors were closely engaged with some of the worst hunger crises in English history. The pointed and detailed attention to food in early modern literature, from luxurious banquets to bare cupboards, I argue, arose from real concerns over the problem of hunger facing the country. I demonstrate how authors developed literary forms seeking to explain and respond to how changing dietary habits and food distribution practices were reshaping their communities. Moreover, early modern authors turned to food not just as a topical referent or as a metaphorical vehicle but rather as a structural concern that could be materially addressed through literary means. Each chapter of “Ruling Appetites” centers on particular literary techniques—verse forms, stage characters, theatrical set pieces, or narrative tropes—through which authors examined how food influenced economic, social, and political reality. -

Richard Lovelace

Richard Lovelace: Royalist Poetry in Context, 1639–1649 Susan Alice Clarke A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2010 I, Susan Alice Clarke, hereby declare that, except where otherwise indicated in the customary manner and to the best of my knowledge and belief, this work is my own and it has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other university or institution. ………………………………………….. July 2010 S.A Clarke ii For Allen and Mary Pickering In memoriam iii Acknowledgments Many people have helped me to bring this study to completion. First, my supervisor, Dr Ian Higgins, has overseen the project from its inception. He has been patient and generous with his valuable advice. He has also encouraged further effort. I thank him for all aspects of his assistance. I could not have hoped for a better supervisor. The Australian National University has supported my work through the provision of travel grants which facilitated visits to British research institutions, primarily the Bodleian Library, Oxford; The National Archives; and the Centre for Kentish Studies. I also profited from time spent at the British Library; the London Metropolitan Archives; and the University of Cambridge Library. Dr Johanna Parker, Librarian at Worcester College, Oxford, provided access to the College’s resources on Lovelace and his editor, C.H. Wilkinson. The travel grants allowed me to attend conferences at the Centre for Seventeenth-Century Studies, Durham (2003), the ‘Royalists and Royalism’ conference at Clare College, Cambridge (2004), and ‘Exile in the English Revolution’ at the University of London (2006).