X«Rox Univoralty Microfilms Soo Northzootoroad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PI Classification Schedule GLRG.Xlsx

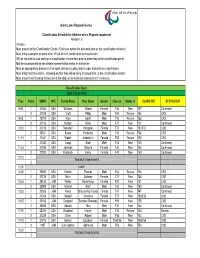

Great Lakes Regional Games Classification Schedule for Athletes with a Physical Impairment Version 1.6 Athletes - Must present to the Classification Centre 15 minutes before the allocated time on the classification schedule. Must bring a passport or some other official form of identification to classification. Will be required to read and sign a classification release form prior to presenting to the classification panel. May be accompanied by one athlete representative and/or an interpreter. Must be appropriately dressed in their sport clothes including shorts under tracksuits and sport shoes. Must bring their track chairs, strapping etc that they will be using in competition, to the classification session. Must ensure their throwing frames are at the stadium for technical assessments if necessary. Classification Day 1 Date: 9 June 2016 Time Panel SDMS NPC Family Name First Name Gender Class In Status In CLASS OUT STATUS OUT 9:00 1 31066 USA Williams Taleah Female T46 New T47 Confirmed 2 31008 USA Croft Philip Male T54 Review T54 CRS 9:45 1 15912 USA Rigo Isaiah Male T53 Review T53 CRS 2 31016 USA Nelson Brian Male F37 New F37 Confirmed 10:30 1 31218 USA Beaudoin Margaret Female T37 New T37/F37 CNS 2 30821 USA Evans Frederick Male T34 Review F34 CRS 11:15 1 11241 USA Weber Amberlynn Female T53 Review T53 CRS 2 31330 USA Langi Siale Male F43 New F43 Confirmed 11:45 1 31098 USA Johnson Shayna Female T44 New T44 Confirmed 2 27200 USA Frederick Emily Female F40 New F40 Confirmed 12:15 1 Technical Assessments 2 13:00 Lunch 14:00 1 20880 USA -

Para Athletics Classification Are You, Or Do You Know Someone Who May Be, Interested in Para Athletics?

PARA ATHLETICS CLASSIFICATION ARE YOU, OR DO YOU KNOW SOMEONE WHO MAY BE, INTERESTED IN PARA ATHLETICS? Classification determines who is eligible to compete in a Para sport and then groups the eligible athletes into sport classes according to their activity limitation in a certain sport or event. Athletes are classified as “T” (Track and Jump) or “F” (Field) based on which event they are competing in, followed by a number that represents impairment type and level of impairment. For example, T12. First Letter Represents: First Number Represents: Second Number Represents: T/F TRACK OR FIELD 1-6 IMPAIRMENT TYPE 1-8 DESCRIPTION OF IMPAIRMENT Typically T identifies a track 1 = Visual Impairment The number 1 through 8 specifies event and F for a field event. 2 = Intellectual Impairment the description of the impairment as There are certain exceptions 3 = Co-ordination Impairment per the classification rules (i.e. Long Jump is a T event) 4 = Upper Limb Deficiencies; Lower Limb Deficiencies without the use of prosthetic; short stature 5 = Impaired muscle power or range of movement 6 = Limb deficiencies with the use of prosthetic PHYSICAL IMPAIRMENT SHORT STATURE F40 F41 IMPAIRED MUSCLE POWER AND/OR PASSIVE RANGE OF MOVEMENT T/F51 T/F52 T/F53 T/F54 F55 F56 F57 Athletes who compete seated LIMB DEFICIENCY T/F42 T/F43 T/F44 T/F62 T/F63 T/F64 T/F45 T/F46 T/47 Lower limb deficiency without Lower limb deficiency with Upper limb deficiency the use of a prosthetic the use of a prosthetic with or without the use of a prosthetic ATHLETES WITH ATHETOSIS, ATAXIA AND/OR -

Athletics Classification Rules and Regulations 2

IPC ATHLETICS International Paralympic Committee Athletics Classifi cation Rules and Regulations January 2016 O cial IPC Athletics Partner www.paralympic.org/athleticswww.ipc-athletics.org @IPCAthletics ParalympicSport.TV /IPCAthletics Recognition Page IPC Athletics.indd 1 11/12/2013 10:12:43 Purpose and Organisation of these Rules ................................................................................. 4 Purpose ............................................................................................................................... 4 Organisation ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Article One - Scope and Application .................................................................................. 6 International Classification ................................................................................................... 6 Interpretation, Commencement and Amendment ................................................................. 6 2 Article Two – Classification Personnel .............................................................................. 8 Classification Personnel ....................................................................................................... 8 Classifier Competencies, Qualifications and Responsibilities ................................................ 9 3 Article Three - Classification Panels ................................................................................ 11 4 Article Four -

Sediment Thickness

Status of Environmental Work Carried out by India Dr. S.K.Das Ministry of Earth Sciences Government of India 9th November, 2010 Kingston, Jamaica Objectives • To establish baseline conditions of deep-sea environment in the proposed mining area To assess the potential impact of nodule mining on marine ecosystem To understand the processes of restoration and recolonisation of benthic environment To provide environmental inputs for designing and undertaking a deep-sea mining operation. Activities and milestones achieved Activity Period Status • Baseline data collection 1996 - 1997 Completed • Selection of T & R sites 1997 Completed • Benthic Disturbance and 1997-2001 Completed impact assessment • First monitoring studies 2001-2002 Completed • Second monitoring studies 2002-2003 Completed • Third monitoring 2003-2004 Completed • Fourth monitoring 2005 Completed • Environmental variability study 2003-2007 Completed • Evaluation of nodule associated 2008 onwards Continuing micro-environ. Creation of environmental database 2011 onwards Continuing Environmental studies for marine mining in Central Indian Basin Phase 1: Baseline data collection Phase 2: Benthic Disturbance & Impact Assessment Phase 3: Monitoring of restoration modeling of plume creation of environmental database 4 PARAMETERS ANALYSED Geology Biology Chemistry •Seafloor features •Surface productivity • Metals •Microbiology •Sediment thickness • Nutrients •Biochemistry •Topography • Meiofauna • DOC • Macrofauna •Sediment sizes • POC •Megafauna •Porewater and sediment chemistry Physics •Geotechnical • Currents props. • Temperature • Conductivity •Stratigraphy • Meteorology 5 Benthic Disturbance (1997) * 200 x 3000 m * 5400 m depth *Central Indian Basin * 26 tows * 9 days * 47 hrs * 88 km * 3737 t (wet) / 580 t (dry) sediment re-suspended 6 Results of different parameters in diff. Phases (4cm from top in disturbance zone) Parameter Pre-dist. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other -

Mechanisms Affecting Liquefaction Screening of Non-Plastic Silty Soils Using Cone Penetration Resistance

Mechanisms affecting liquefaction screening of Non-Plastic silty soils using Cone Penetration Resistance USGS Award Number: 07HQGR0113 Final Report October 2014 S. Thevanayagam Principal Investigator & V. Veluchamy and Q. Huang Research Assistants University at Buffalo State University of New York Department of Civil, Struct. & Env. Eng. 212 Ketter Hall, Buffalo, NY 14260 Tel: 716-645-4376; [email protected] Program Element: III Key Words: Liquefaction, sand, silty sand, Cone Penetration Resistance "Research supported by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Department of the Interior, under USGS award number (07HQGR0113). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Government." i Abstract Effect of non-plastic fines on the cone resistance and cyclic resistance of sands and silty sands remains an unresolved problem. This study focuses on: (a) cone penetrometer experiment study on penetration resistance of sands and silty sands at 15 and 25% silt content, (b) numerical study on the effect of permeability and compressibility (representing the effect of silt content), diameter of cone (dc) and penetration rate (v) on cone resistance in sands and silty sands, (c) comparative analysis of the results from (a) and (b) of the effect of silt content on cone resistance through a non-dimensional parameter To (=vdc/cv, where v is the penetration rate, dc is the cone diameter and cv is the coefficient of consolidation) for all soils at the same equivalent inter-granular relative void ratio [(ec)eq] or relative density [(Drc)eq], and (d) relationship between cyclic resistance and cone penetration resistance and the non-dimensional parameter To, and its utility for liquefaction screening. -

Para Throws Coaching Manual

Para Throws Coaching Manual A Technical Guide for Coaching Athletes with a Disability in Para Throws Acknowledgments LEAD PROJECT CONTRIBUTORS Ken Hall, ChPC – Former National Team Para Throws Coach, Athletics Canada and current Provincial Para Throws Coach, Ontario CP Sports Association and Cruisers Sports for the Physically Disabled Lisa Myers – Program Manager and Provincial Seated Throws Coach, BC Wheelchair Sports Association ADDITIONAL CONTRIBUTORS Kim Cousins, ChPC – Paralympic Next Gen Manager and National Team Coach, Athletics Canada Jennifer Schutz, ChPC – Coaching Education Coordinator, BC Athletics PHOTOS Photos included throughout this manual are provided by: Rita Davidson Sue Furey Gerry Kripps Paul Lengyell BC Wheelchair Sports Association would like to thank the Government of Canada, Province of British Columbia, and viaSport for their generous support in the production of this manual. © 2017 BC Wheelchair Sports Association | Para Throws Coaching Manual 1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................4 What is Para Throws? .............................................................................................................................................4 Classification ...............................................................................................................................................................4 Characteristics of Disability Groups ............................................................................................................................5 -

(VA) Veteran Monthly Assistance Allowance for Disabled Veterans

Revised May 23, 2019 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veteran Monthly Assistance Allowance for Disabled Veterans Training in Paralympic and Olympic Sports Program (VMAA) In partnership with the United States Olympic Committee and other Olympic and Paralympic entities within the United States, VA supports eligible service and non-service-connected military Veterans in their efforts to represent the USA at the Paralympic Games, Olympic Games and other international sport competitions. The VA Office of National Veterans Sports Programs & Special Events provides a monthly assistance allowance for disabled Veterans training in Paralympic sports, as well as certain disabled Veterans selected for or competing with the national Olympic Team, as authorized by 38 U.S.C. 322(d) and Section 703 of the Veterans’ Benefits Improvement Act of 2008. Through the program, VA will pay a monthly allowance to a Veteran with either a service-connected or non-service-connected disability if the Veteran meets the minimum military standards or higher (i.e. Emerging Athlete or National Team) in his or her respective Paralympic sport at a recognized competition. In addition to making the VMAA standard, an athlete must also be nationally or internationally classified by his or her respective Paralympic sport federation as eligible for Paralympic competition. VA will also pay a monthly allowance to a Veteran with a service-connected disability rated 30 percent or greater by VA who is selected for a national Olympic Team for any month in which the Veteran is competing in any event sanctioned by the National Governing Bodies of the Olympic Sport in the United State, in accordance with P.L. -

"Browns Ferry Nuclear Plant Annual Exercise Scenario."

Browns Ferry 1992 Graded Exercise Controller Listing T~ele hone ~Pa er Exercise Coordinator C. T. Benton 39644 Lead CECC Controller Tom Adkins 751-1656 39379 Evaluator Larry Smith 751-1656 Plant Asmt Jimmy Johnson 751-1656 Rad Asmt Betsy Eiford-Lee 751-1658 Public Information Barbara Martocci 751-1724 RMCC Controller Dan Winstead 355-0206 Van Controller Ronald Morrison Van Controller Ellen Hensley Van Controller James Troxell REP Van 9144 Cellular Phone —205-656-7626 then 205-667-9904 REP Van 9131 Cellular Phone —205-656-9623 Lead Simulator Controller Eddie Howard 729-3451, 3452, 3975, 4985 Simulator Controller Thomas Taylor Simulator Operator John Parshall 729-3451, 3452, 3975, 4985 Simulator Operator Terry Chinn Simulator Evaluator John Beardon 49415 Simulator RadCon Curt Blair 49419 Lead TSC Controller Tony Feltman 90759 Rad Con Kenneth King 39407 Tech Asmt Earl Nave Evaluator David Lambert Lead OSC Controller Randy Ford 39406 Fire Operations R. V. White 39126 Fire Operations Dave Pond 39386 Security Roger Pentecost Evaluator Harry Williamson 99470 Evaluator Nick Catron 39379 Lead Operations Gene Tomlinson Field Controller Marilyn Reeves Field Controller James Johnson Field Controller Nancy Wallette Field Controller Carol Sanders Unit 2 Control Room Terry Balch Lead RadCon Brad Mitchell Rad Con Mike Mitchell Rad Con Vanessa Beers RadCon Henry Schwan RadCon Terry Johnson RadCon Jim Harris 14675 Lead Chemistry Peggy Kirby 14143 Chemistry James Cole Chemistry Stacy Cordes Lead Maintenance Bill Peggram Mechanical Controller Jerry Richardson Mechanical Controller Lynn Turner 10201 Mechanical Controller Jack Watson 10284 Mechanical Controller Doug Koonce Electrical Controller Paul Heck 14926 Electrical Controller Jeff Nauditt Electrical Controller Julian Bass 9212i50239 9209i8 PDR ADOCK 05000259 F PDR Browns Ferry Nuclear Plant 1992 Graded Exercise This document prepared by the Brogans Ferry Scenario Development Team Brogans Ferry Personnel J. -

FEHB) Open Season Approved By: Associate Administrator for Operations and Management

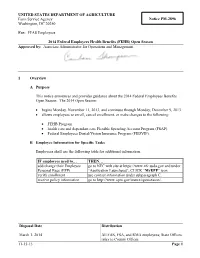

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Farm Service Agency Notice PM-2896 Washington, DC 20250 For: FFAS Employees 2014 Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) Open Season Approved by: Associate Administrator for Operations and Management 1 Overview A Purpose This notice announces and provides guidance about the 2014 Federal Employees Benefits Open Season. The 2014 Open Season: • begins Monday, November 11, 2013, and continues through Monday, December 9, 2013 • allows employees to enroll, cancel enrollment, or make changes to the following: • FEHB Program • health care and dependent care Flexible Spending Account Program (FSAP) • Federal Employees Dental/Vision Insurance Program (FEDVIP). B Employee Information for Specific Tasks Employees shall use the following table for additional information. IF employees need to… THEN… add/change their Employee go to NFC web site at https://www.nfc.usda.gov and under Personal Page (EPP) “Application Launchpad”, CLICK “MyEPP” icon. verify enrollment use contact information under subparagraph C. receive policy information go to http://www.opm.gov/insure/openseason/. Disposal Date Distribution March 1, 2014 All FAS, FSA, and RMA employees; State Offices relay to County Offices 11-15-13 Page 1 Notice PM-2896 1 Overview (Continued) C Human Resources Division (HRD) Contacts This table provides HRD contacts. IF employee is located in… THEN contact… • Kansas City (KC) or St. Louis, Dana Candler, HRD, at by either of the following: ITSD • e-mail to [email protected] • KCCO • telephone at 816-926-6117. • APFO Patty Gepford, HRD, at by either of the following: • KC or St. Louis, OBF, Policy, • e-mail to [email protected] Accounting, Reporting, and Loan • telephone at 816-926-6259. -

Seated Throws

Information, Equipment and Funding: Seated Throws Seated Throws Seated, or secured, throwing takes place in a throws circle. The events cover shot, javelin, discus and club and are available to those athletes that are unable to stand and/or have balance and stability problems that make throwing from an ambulant position difficult. Athletes in the seated throwing events throw from either their day chairs, or from custom made throwing frames, which are secured to the ground by straps. Classification & Eligibility The impairments and classifications associated with seated throwing events are: u Athletes with cerebral palsy (or similar) - F31, F32, F33, F34 u Athletes with spinal injury - F51, F52, F53, F54, F55, F56 u Athletes with lower limb loss (or similar) - F57 Classification is coordinated nationally by British Athletics. A classification is required to enter all Parallel Success competitions and for results to be recognised on the UK Rankings (www.thepowerof10.info). u For ‘An Introduction to Classification’ video and downloadable factsheet visit: http://ucoach.com/video/an-introduction-to-classification-in-athletics u For more information and changes to eligibility rules see IPC Athletics: www.paralympic.org/Athletics/RulesandRegulations/Classification page 1 Throwing Frames Throwing frames are individually designed assistive devices which are scaffold-like chairs made of metal bars and plates welded together. The main purpose of the throwing frame is to assist in weight bearing. Consequently, it contributes to the performance of an athlete by enabling the optimum throwing action (range of Seated Throws movement, velocity of body segments, final body position at release etc).* A variety of different classes are eligible to compete in seated throws, consequently, there is a range of frames within and between the different classes of athletes. -

Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games

TOKYO 2020 PARALYMPIC GAMES QUALIFICATION REGULATIONS REVISED EDITION, APRIL 2021 INTERNATIONAL PARALYMPIC COMMITTEE 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games Programme Overview 3. General IPC Regulations on Eligibility 4. IPC Redistribution Policy of Vacant Qualification Slots 5. Universality Wild Cards 6. Key Dates 7. Archery 8. Athletics 9. Badminton 10. Boccia 11. Canoe 12. Cycling (Track and Road) 13. Equestrian 14. Football 5-a-side 15. Goalball 16. Judo 17. Powerlifting 18. Rowing 19. Shooting 20. Swimming 21. Table Tennis 22. Taekwondo 23. Triathlon 24. Volleyball (Sitting) 25. Wheelchair Basketball 26. Wheelchair Fencing 27. Wheelchair Rugby 28. Wheelchair Tennis 29. Glossary 30. Register of Updates INTERNATIONAL PARALYMPIC COMMITTEE 3 INTRODUCTION These Qualification Regulations (Regulations) describe in detail how athletes and teams can qualify for the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games in each of the twenty- two (22) sports on the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games Programme (Games Programme). It provides to the National Paralympic Committees (NPCs), to National Federations (NFs), to sports administrators, coaches and to the athletes themselves the conditions that allow participation in the signature event of the Paralympic Movement. These Regulations present: • an overview of the Games Programme; • the general IPC regulations on eligibility; • the specific qualification criteria for each sport (in alphabetical order); and • a glossary of the terminology used throughout the Regulations. STRUCTURE OF SPORT-SPECIFIC QUALIFICATION